Paris’s Les Halles in the 1e arrondissement used to house a vibrant wholesale market, which, once-upon-a-time, was regarded as the beating heart of the city. That was until it was bulldozed in 1971 to make way for a shopping mall and garden maze where drug dealers could hang out in the daytime and set up shop. Recently it’s been upgraded to a giant canopy with a multi storey shopping centre underneath, but its functional opulence is a far cry from the predominantly white working class nerve centre that it once was; Emile Zola called it le ventre de Paris or “the belly of Paris”. You can find stunning old photographs by Robert Doisneau online, featuring everything from offal stands to accordion players, and French folk going about their business buying sheep’s heads from smoking commerçants in bloodied aprons.

The prolétariat are underrepresented in central Paris these days (the market was relocated to the southern suburb of Rungis), and good old fashioned grit is in short supply, but the 10e arrondissement where Acid Arab hail from, is as close as you’ll come these days to a pulse. Along with its neighbour the 11eme, the 10eme is young, multiethnic and multicultural, taking in the drunken chaos of Strasbourg Saint-Denis, the sociable urbanity of wine picnics along the Canal Saint-Martin and the urban vibrancy of Boulevard de la Chapelle. In and amongst all the Turkish markets and Moroccan eating emporiums, the bars and hipster cafes and the international train stations in between, are a rich mix of poor and bobo (historian Eric Hazan defines bobos – or bohemian bourgeois – as the “intellectuals, artists, designers, journalists— who cultivate their superficial non-conformism and benign anti-racism in these quarters while driving up the rents with the help of property speculators”). The 10eme is the sort of region that forever threatens to become gentrified, but never actually quite does.

In my not so humble opinion, you can stick the cutsie Montmartre postcard tweeness of Amelie or the plush mise-en-scene of the 16eme in Last Tango In Paris, because for me it’s the thrilling cultural melting pot of the north east of Paris away from the tourists where all the interesting stuff is happening these days. And if the 10eme and 11eme had a defining sound, then they might sound a bit like Acid Arab.

Guido Minisky and Hervé Carvalho started out DJing in 2012, and since then they’ve been reaching out to others to collaborate in order to realise the sound in their heads. Personnel on this record includes Kenzi Bourras, who has been playing keys with them from the beginning, and Syrian King of the Keyboard Rizan Said (not to be confused with Cairo keyboard king Islam Chipsy; Said is known for his sterling work with Omar Souleyman). Other guests include Israeli trio A-WA, Turkish musician Cem Yildiz and Algerian singer and activist Rachid Taha. In an interview with The Guardian in 2014, the duo insisted their raison d’etre wasn’t about appropriation or being "flagbearers of exotic shit", but instead their mission was to be “representative of our days".

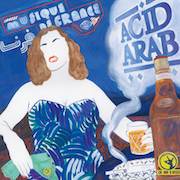

It’s a sad indictment on our times then that the title of their debut album, Musique de France, somehow sounds controversial. Of course, other than the irrefutable fact it is what it says it is, it’s also provocation, a gauntlet thrown down to challenge bigots to dare to contest its veracity. There are doubtless many hardcore Le Pen supporters vivre à la campagne who would not equate Musique de France with what they perceive as the music of France, but then they’d probably balk at Daft Punk or Justice too, if for different reasons. The blast of bouzouki on opener ‘Buzq Blues’ would bamboozle any cloth-eared Baby boomer if the swinging metronome and handclaps didn’t disorientate them first, but this rhythmical coalescence would more likely send a congregation into ecstasy if struck up in any club. Not since the 1950s have generations been so disparate and their divergent cultures so misunderstood by one another.

It’s probably important to state at this point that this LP is not a political record (and Acid Arab not a political movement); Musique de France should make one shake one’s pants and that it manages to do with aplomb. ‘La Hafla’ is one of the catchiest bangers of the year with all the twilight ambience of an evening jam in a north African square; ‘Le Disco’, with its proggy finger-tapping (of which instrument I’m not sure) and incessant woodblock, is punishing; ‘Sayarat 303’ is deliciously trancey, while ‘Gul l’Abi’ with A-WA takes a break from the trance to deliver something altogether more dubby and smooth.

As residents of the 10eme, the sounds on this record belong to Acid Arab as much as they might belong to anywhere else. Musique de France isn’t an indiscriminate smash and grab of appropriation, it’s a wonderfully organic and experimental and occasionally psychedelic record that will take you to interesting places if you’ll let it. It’s not some Frankenstein musical cross-breed or fusion, it’s what Paris sounds like if you happen to be Guido Minisky and Hervé Carvalho. It might be zeitgeisty, but once the hype dies down, Acid Arab are surely here to stay…

Unlike the market at Les Halles.