When I became fascinated with 10cc in the late 80s, nothing could have seemed less current. That’s not just a turn of phrase. I’m trying to think of things that might have. I can’t. Even Status Quo were invited to open Live Aid. Yes were in the charts. That’s right, Yes. 10cc, by contrast, were in the bargain boxes at the second-hand record fairs where I did my monthly rounds. I bought everything I could find by them. I couldn’t work out why I liked them. I didn’t like anything else like them. It took me a while to realise there wasn’t anything else like them. Or rather, there were lots of things that were a bit like bits of them, but nothing at all that was like all of them, all at once.

10cc were weird, in one of the weirdest ways. They were weird in a middle-of-the-road way. The road itself was cut through ever-changing terrain and full of hairpin turns. They were weird by subterfuge. Undercover weird. People thought 10cc were bland, if they thought about 10cc at all. People were wrong. 10cc sounded bland only if you weren’t listening. I was listening – not because I was smarter or more alert than anybody else, nor because I was one of those dreary twerps who embraces what most dismiss purely because most dismiss it. It was because I couldn’t help it. There was so much stuff going on here that kept snagging my attention.

The other sleeves stacked up beside my second-hand Thorens turntable bore the legends "New Order" or "Cocteau Twins" or "Talking Heads" – I was catching up, y’see, for one reason and another – and that was all very commendable, according to folk who knew about this sort of thing. But what the hell was Deceptive Bends doing there? Or Bloody Tourists?

They were right about Bloody Tourists. It was bloody awful. It had the chart-topping ‘Dreadlock Holiday’ on it, which was the last thing everybody remembered about 10cc; which I found repellent from the first time I heard it; and which underpins Bennun’s First (and only) Law Of Reggae: only those who play nothing but reggae should be permitted to play reggae at all. Yes, I know. The Clash. Elvis Costello. But think about it. From Eric Clapton via 10cc through to Olly Cunting Murs, is there anything more cringe-inducing than dabblers in reggae? Especially when they do the accents.

So that was where it all went finally, decisively wrong. If understandably so.10cc had been genre-hopping dilettantes throughout their existence up to that point, so why stop at reggae? Before that it had gone wonkily, enliveningly, erratically right: one of those great, prolific runs some acts will speed through, an album a year for five years, from ’73 to ’77, each crammed with more ideas, more tunes, more ambition, more indulgence, more experimentation – the experimentation is what excused the indulgence – than most acts will find room for in a career.

What were 10cc? Prog rock? Art rock? Soft rock? AOR? Chart pop? Yes. There were four of them, all of whom wanted to be John and Paul and George, and were happy to take their turn as Ringo. They could do the comic without descending into gimmickry. No band after The Beatles had been so daffily diverse, nor has any since. Two of them (Eric Stewart, Graham Gouldman) had been proper 60s pop types. Two of them (Kevin Godley, Lol Creme) were capital-A Art pranksters. At their headquarters, Strawberry Studios, Stockport, they worked in ever shifting combinations to create mocking, loving enhancements and mutations of early rock & roll, doo wop, FM radio fodder, production numbers for imaginary musicals, operetta, lounge/easy listening – and straight-up 70s rock that wasn’t straight-up, parodied the 70s even as they happened, but undoubtedly rocked. They were a power-pop Pink Floyd. An eclectic light orchestra. But never any one thing for long.

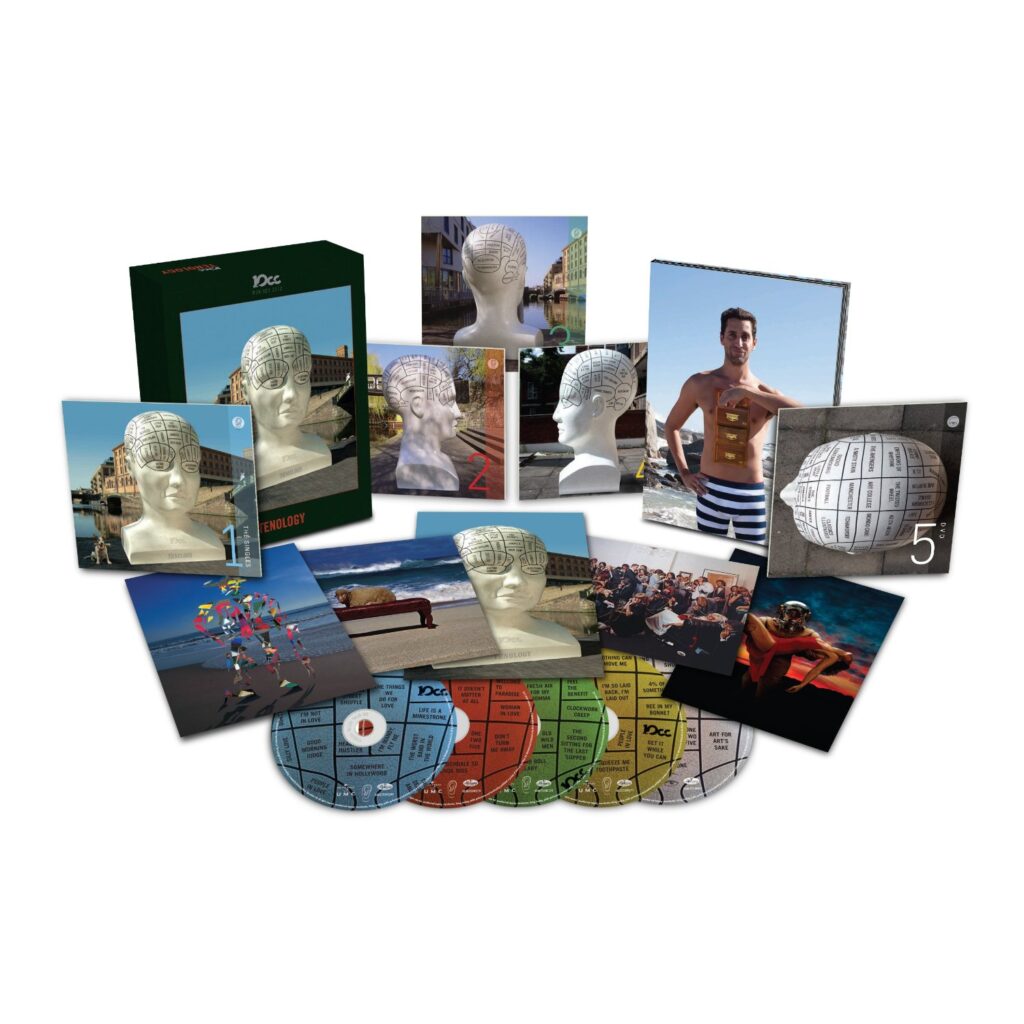

Their peers made concept albums. 10cc made concept singles. Such as their first, ‘Donna’, a sweet, hilarious Frankie Valli-style number, akin to Frank Zappa without the superior sneer – which is to say, immeasurably preferable. And that, at last, brings us to this four-CD/one-DVD box set, and an opening disc of singles which expands upon any 10cc best-of, and is thus altogether marvellous. ‘Rubber Bullets’! ‘The Wall Street Shuffle’! ‘Art For Art’s Sake’! ("Money, for God’s sake," pleads its bathetic corollary.)

There is a recognition in the way the set is assembled – with almost all the audio from 1978 onwards confined to disc two, as if to admit it into the record but prevent it adulterating the good gear – of how 10cc’s golden era gave way almost instantaneously to their wooden one. One moment they were, after Godley and Creme’s departure, producing Deceptive Bends, one of the great power-pop albums of the 70s. The next, it was cod-Jamaican novelty dross and – implausibly – it managed to go downhill from there.

Thus discs one (singles) and three (album tracks) are treasure troves, teeming with gems and curios, while four (b-sides and rarities) has its occasional charms. This oeuvre has been raided over time by J Dilla and Gayngs (the latter developed an entire album around the mood and tempo of ‘I’m Not In Love’). One hears it speculated that their three-part rock-opera suite ‘Une Nuit A Paris’ nudged Queen to embark upon ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. (If so, 10cc returned the compliment with their video for ‘I’m Mandy, Fly Me’, mirroring Queen’s ‘Rhapsody’ clip, and perhaps slyly claiming a certain precedence.)

Disc two I’ve revisited in the hope of finding delights that eluded me first time around, but no. It’s tepid at best, and more frequently turgid. The DVD is a treat, though, and the videos for the duff later tunes are enjoyable period pieces.

The parallel that keeps coming back is the Floyd one. ‘Take Art For Art’s Sake’. A caustic reprimand of avarice elliptically constructed upon blues-rock: sound familiar? Where Floyd’s ‘Money’ is clunky and indignant, though, 10cc’s number is supple and droll and cutting, their chief targets being musicians who suddenly discover reactionary, grasping tendencies upon becoming minted.

The dichotomy is summed up by the two bands’ artwork. Storm Thorgerson was chiefly responsible for both. For the solemn Floyd, he devised a kind of hollow, glossy surrealism, the form of the thing without the furtive meaning of the thing that makes the thing what it is. Never more so than on their own box set, Shine On. For 10cc, he created elaborate jokes, such as the inner gatefold of How Dare You, depicting a crowded party at which everyone is on the telephone, oblivious to their fellow guests. Take away the cords and it presciently evokes most of the social functions I’ve attended in the last ten years.

The cover for Tenology is just about perfect. It starts with a pun – a phrenology (geddit?) head, upon which are inscribed sundry 10cc influences, foregrounded against what look like Mancunian canalside Victorian warehouses. Tiny visual gags reward closer inspection, just as aural ones do careful listening. The effect recalls the spooky cityscapes of surrealist progenitor Giorgio De Chirico, populated only by masks and mannequins, and also beautifully spoofs Thorgerson’s own portentous Floyd graphics.

Tenology itself, to recap, is not perfect, or even close. But half of it is a lucky-dip of madcap ingenuity and variation from one of the few pop bands to render cleverness a virtue rather than an irritation. Turns out I was right first time. Which is not to my credit in the least, but very much to 10cc’s.