My last piece started with a question set by historian Oleksandr Alforov, what do we Ukrainians fight for in this war? As an answer, I began to map out the cultural front in this struggle for our existence and identity, something that many musicians have been active in. Now I look to an uncertain and dangerous future.

The Choice

2023 was a positive year for music growth, but at the same time, obviously, everything was already much harsher for men. At some point the government made foreign tours much more difficult, even impossible, for some artists, and the mobilisation effort tripled, with more than 1,000 conflicts between civilians and the mobilisation officers being reported. Queues of those willing to serve were long gone, and the promise of a two, or three week war became a joke. The russians never stopped attacking. They constantly tried to break the front in different places, so additional soldiers were needed more and more urgently. On top of that, help from the USA was constantly delayed, a captive of their inner political struggle.

During this period one began to behave like the frog slowly being cooked. Although the state pressure was growing visibly, societal pressure, in my opinion, was not as heavy, because, well, society has their own men to protect. So generally it was a good period for stable and even peaceful growth for our music industry.

And now it is 2024. It is not as if a lot has visibly changed from the previous year, outside of more concerted control from the state over the men, and inevitable tax rises, but the frog finally felt the heat. In my view, the year 2024 is when we felt the war’s actual influence on our music scene. At this point, a lot of people were already mobilised, and some dead. Also, more and more talented men felt like they were obliged to join the army. My fellow journalist and music blogger Ramone Spinach, who joined the army willingly this July, has been mentally preparing for this moment for two years: “I always knew that sooner or later I would join the army. It is an honour to take part in the fight for liberty, no matter how hard it is to let go of your well-fed and comfortable life. I tried to help the army with donations and active volunteering. But that was not enough.”

His words capture the feelings of other men in the same article, and also on social media. But because of this wave of men joining the army with positive motivations, I would assume that the inner pressure for musicians grew a lot. The pressure to make the choice: how do you help your country now? What are your limitations? Health problems or supporting older relatives are big factors for many. The new Ukrainian minister of culture, Mykola Tochytskyi recently said: “Today, culture must be at the front and for victory. We must unite for this goal. In addition to our own efforts, our struggle is on the front lines and the preservation of cultural identity needs increased support from our foreign partners. International aid depends not least on understanding the motives and goals of our struggle. We need to communicate to our friends well so that they know who we are, what we are for, and why we are there.”

Tochytskyi’s words don’t represent the actual state of mobilisation at present, but they represent the government’s public stance that culture may have some special status and mission, even in these wartime conditions.

At the same time, we find some artists who actually don’t agree that they deserve some special status or privileges. Denys Zhukovskyi, O’Hamsters and Guerilla Noir drummer, and now also in the Ukrainian army, expressed many times that there is a great resentment against the state in the Ukrainian metal scene because the government does not allow musicians to tour abroad and spread the truth about the war, or collect donations for the Ukrainian army. Zhukovskyi wants us musicians to “be honest with ourselves and say sincerely: we just want to play concerts and feel that the business we love is still alive, but the state has taken away this opportunity from us. There is no cultural diplomacy that will change the mind of drunken metalheads hungover at a concert. They will listen to these tirades from the stage, go home, turn on some russian band, and not care about Ukraine again.”

One of Zhukovskyi’s bands, Guerilla Noir, have recently released one of the darkest albums about this war. In his view, musicians would just look for privileged status in a country. Zhukovskyi: “And what about our agronomists? Or sailors and engineers? I don’t want to offend anyone, but I think that even if all our bands were abroad tomorrow, the tolerance of russians at big festivals, or the perception of this war by Western metalheads would not change.”

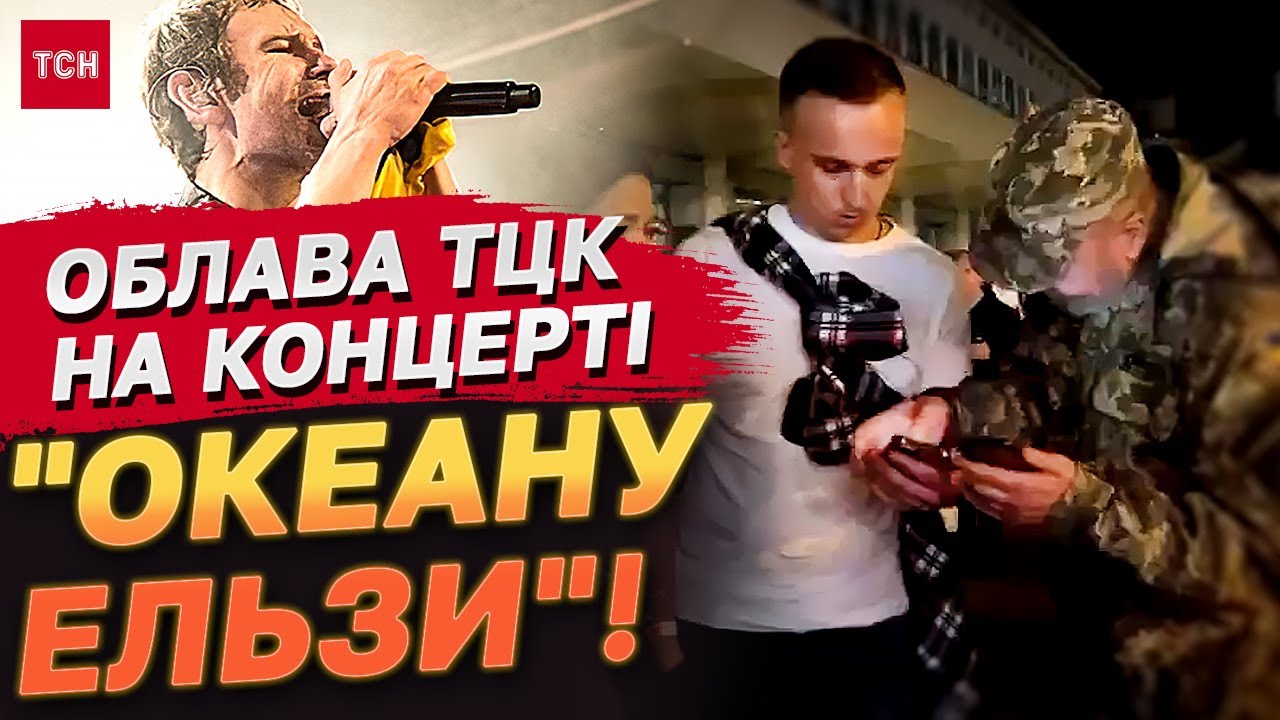

Just a few days after his comments, the government proved that the culture is no exception after all. On 11 October, in the evening after a concert by the biggest Ukrainian rock band Океан Ельзи (Elsa Ocean), thousands of visitors were greeted on the exit by police and mobilisation officers, who checked the men’s documents; some people were captured on the spot. These actions, never seen before on such a scale, happened that same evening in many places throughout the country, symbolising a new and more dangerous era for our concert industry.

The chairman of the Verkhovna Rada Committee on Humanitarian and Information Policy Mykyta Poturaiev, commented that he did not consider document verification after the Okean Elzy concert to be a threat to Ukrainian culture, seeing it on a parallel with document checks in bars or clubs themselves “not a threat to the Ukrainian economy”. Poturaiev welcomes such inspections, believing they should be comprehensive and permanent.

New concerts may be announced, but just as the number of visitors and tours declined through 2024 due to the gradual increase of mobilisation efforts, the decline will increase with an expectation of more strict checks at events. So the inner pressure for musicians is now combined with the quite realistic outer one.

What’s next?

The war had the unexpected result of Ukraine’s music culture growing rapidly. But now many industry players note that this wave of pure interest is already over and the time for hard work has come. We feel both inner and state pressure. So what will be the future of our metal industry? Nobody knows, but our heroes express some thoughts. Artem Trubetskoi notes that because the russians did not retreat, the state introduced even stricter restrictions on public rights and freedoms. “Many band members are in the army, others do not get permission to go abroad with charity missions. And the attention on the metal scene is decreasing a little, but we should thank all those who continue to play, create and tour, because the mental health of peaceful people is just as important as that of artists. All that should remain unchanged is music donations for the military.”

Denys Zhukovskyi, on the contrary, thinks that the situation will get worse, with fewer concerts and festivals, and, with each new day of this war, less new music: ‘I know bands that have stopped all activities because someone from the line-up is mobilised, and festivals that are no longer held for the same reason. I also know enough cases when people simply do not leave their homes or travel to other regions because they are afraid of being mobilised. This will naturally affect the scene.’

Denys, just like Kyrylo Brener from КАТ, mentioned in part one, argues that serving in the army, and a lack of inspiration “to write at least one text line, or come up with at least one melody” feels like a bigger threat to the industry in general. Kyrylo, tries to add a bit of positivity for our music future: “Young bands will develop, tour the country and play music. There is a change of generations taking place, although not voluntarily, but it is what it is. I think that in a year it will be even more noticeable than now.”

Kyrylo thinks the lack of foreign artists performing in Ukraine will only support this generational change.

And to sum up from me. Obviously we still have the women’s potential, which grows in the scene (see previous articles) and we have a younger generation who are just entering. But to develop the industry at this rate, we still need those big, more experienced players, who are mostly men; that is the reality. And who knows, mobilisation is maybe also on the plate for women or younger men in the foreseeable future. We should assume that this war won’t end in a year or two. Therefore, the choice between operating a drone or holding a microphone in one’s hands is quite a challenge over here. So: you tell me, what would you choose?