“You say you are a socialist and you say you hate Nazis but that is contradictory as they are the same thing.”

There’s a sound in the room just at the threshold of hearing which I will later realise is a combination of sharp inhalation, many heads being shook in disagreement and people sighing. I look at the very serious, unblinking, young man and I am stunned, temporarily unable to summon speech, so he adds with a small flourish: “Nazi comes from national socialist; it’s the same thing.”

When you hear this stuff vocalised for the first time, to be fair, it is far less aggravating than seeing it written across your laptop screen. I start laughing: “Ha ha ha! What? Oh… you’re not joking.”

I sigh off mic and then add: “They’re not the same thing but I’m also not going to get drawn into some pedantic argument about semantics when you absolutely understand what I mean.”

It’s also interesting to note that when you’re in the same room with someone who may or may not have been nibbling away at the red pills, and there are plenty of other people present who clearly see that what he’s saying is absurd, the idea of going full nuclear just isn’t that tempting.

He continues: “Nazism comes from national socialism you can look it up on…”

Neither is the temptation to grandstand and humiliate particularly pressing. I start to ask him if he’s ever milked a cowboy due to etymological confusion but looking around the room, there’s just no need: he’s on his own: “Look. First of all I didn’t say I was a socialist. I said I had some fundamental beliefs that could be described as socialist. Whether I can describe these beliefs in sophisticated or academic terms or live up to them and do anything to manifest them in the world at large is another issue but they are my beliefs.”

He still hasn’t blinked: “But Nazis and socialists are the same thing…”

Talking to people face to face does give you the luxury of trying out different, more productive avenues to explore: “Look. You’re fixated on a word in abstract terms, when what I’m talking about are dynamic actions. It might be pie in the sky…”

I’m speaking in public in Prague and I keep on saying things like “pie in the sky” to a room full of people who have English as a second or third language and, momentarily, I have my mind blown at the oddness of the imagery, visualising the poster for Independence Day but with a huge lemon meringue hovering threateningly above the White House.

“It might be pie in the sky but what I want is for everyone to have shelter, food and clothing when needed, safety from harm and bullying, access to good health care and education, all free of charge at point of access provided in a friendly and dignified manner simply because we have more than enough resources to make this happen. We’ve had some of these things to a certain degree here and in the UK for some time of course but there are now lots of groups working on dismantling these structures and none of them can reasonably be called, or would identify as, socialist, and all of the groups calling for the dismantling come from the right, and some of them are Nazis, no matter what they call themselves. I hope that makes the difference clear.”

He blinks slightly: “So you want good people to move into black metal to combat the bad people; are you a fan of Christian black metal?”

Reading this on a laptop I may have put my fist through the screen at this point but face to face I can tell he’s floundering: “I’m fairly sure you know that’s not what I mean. My main point is that modernist art, like black metal, isn’t encoded with political meaning, it just accrues it by people’s insistence, but it’s not written in stone. If fascists insist that black metal is fascist, people who are antifascist can either meekly agree and back away or noisily disagree and stay. Ideally I guess I’d want a large number of people with heterodox, ethically driven views to visibly occupy territory within metal – or noise, or techno, or industrial or folk – so this will make things harder and harder for the minority of people genuinely driven by extremist dogma, and that’s arguably what’s happening anyway when you look at bands like Panopticon and Dawn Ray’d and Liturgy.”

I look around the room: “Does anyone else have any questions?”

The young man puts his hand up again: “You said that Judas Priest were the first proper heavy metal band, but what does that make the Scorpions?”

And this time it’s me who sighs – audibly, on mic – because now he’s standing on much firmer ground.

Two days earlier I arrive in the Czech Republic, at the invitation of the Gravity Network, to take part in a number of talks on the future of music journalism, to join some informal seminars to help young writers, to take part in a number of interviews and then present a “live documentary performance” about the intersection between heavy metal and modernism with the artist film maker Sapphire Goss.

One of the first people I meet is Jana Kománková and we have a conversation live on air for her show on Radio 1, the first commercial independent station founded in Czechoslovakia after the velvet revolution of 1989. She is incredulous that I like heavy metal. I think we’re of a similar age and it’s hard to guess how different it would have been in the mid-80s listening to either The Smiths or Judas Priest in pre-revolutionary Czechoslovakia; eventually she graciously concedes that Extreme Noise Terror were pushing boundaries in a way that most indie bands in the mid-80s simply weren’t, but that she’d still sooner listen to ‘How Soon Is Now?’ It’s thrilling to be so close to the actuality of underground radio: from Autumn 1990 their transmissions – as Radio Stalin – were broadcast from a bomb shelter built in the catacombs under the empty plinth of a vanished Soviet monument at Letná Hill. During these broadcasts they would play Aphex Twin and My Bloody Valentine to no doubt stunned audiences.

One of my guides around the city for the weekend is Pavel Turek, who has hair which stands – literally – on a radical continuum somewhere between Buzz from the Melvins and Rob Tyner from MC5. He is now one of the country’s old guard when it comes to music journalism, writing for the liberal magazine Respekt but when he was still a student two decades ago he was a Prague tour guide with exactly the same ‘fro, only slightly less grey. He’s happy to revisit his old job for me when we drive past the giant plinth where the 51ft high and 75ft long granite monument no longer stands: “It weighed 17,000 tons, and was unveiled in 1955. You could see Stalin from most of Prague.

“There was a competition to choose the sculptor for the project but submitting a proposal was obligatory. All professions were registered, so every artist living in Prague had to at least suggest a design. Otakar Švec, the artist who ‘won’, sent in a design he thought was crap, but they chose him anyway. He spent years working on it and then killed himself just a few days before the unveiling.”

During the period of de-Stalinisation – the dismantling of the cult of personality – in October 1962, the statue was exploded using 1,800lb of dynamite. A colourful local legend insists that Koba’s gigantic stone noggin rolled all the way down Letná Hill and straight into the Vltava River.

Pavel points out of the car window at a massive empty space: “No one wanted to do it.” The Letna Hill area today appears to be full of people skateboarding.

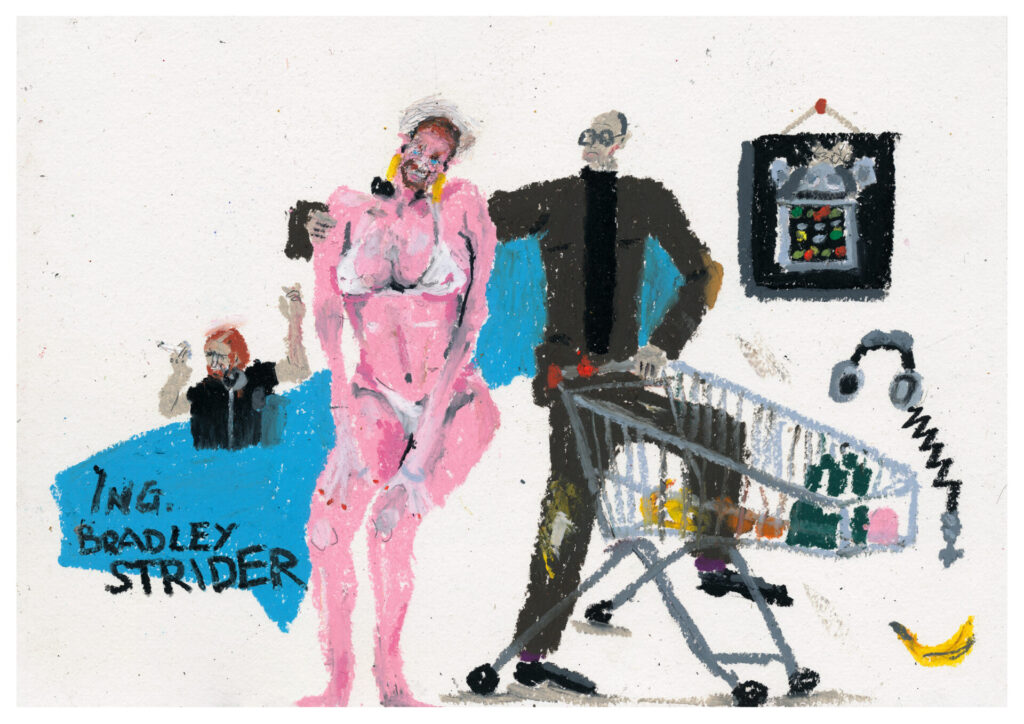

One of my hosts is Jonáš Verešpej, a curator working at the underground techno club Ankali and neighbouring gig venue Planeta Za, a warren of pleasingly dark live rooms, club spaces, meeting rooms and bars, where I go to talk to a young crew of writers for the culture magazine Full Moon, including Editor In Chief Michal Pařízek and occasional cover artist Štěpán Adámek. Štěpán is working on an Aphex Twin fanzine with my friend, the writer and occasional Quietus contributor, Miloš Hroch, and he presents me with two prints of AFX-related art he has created for the project. One features Richard D James in gender-switched ‘Windowlicker’ mode with his arm around a disgruntled but suave looking David Toop pushing a shopping trolley. (The esteemed writer was once stood up by RDJ for an interview outside of a London branch of Sainsburys.)

I recognise the music author Karel Veselý who had previously interviewed me for the leftist Alarm publication. He too is incredulous that I like heavy metal: “Why would you pay intellectual attention to a genre that most people find ridiculous?” Nora Třísková of Heartnoize is a gig promoter as well as writer; she raves about a recent show by Arooj Aftab and her joy at getting to work with Lankum.

I’m at Planeta Za to have a conversation with Miloš in front of an audience titled Music Criticism Under Attack. In preparation he asked me to consider a couple of totemic fashion items. One is Charli XCX’s Insta-friendly T-shirt bearing the rhetorical slogan: “They don’t build statues of critics” and the sunglasses that Anna Wintour wore while sacking scores of Pitchfork staffers.

What to say about Charli’s fine T-shirt? The city of my childhood was Liverpool, the city of my young personhood was Hull, the city of my adulthood was London, and now, the city of my middle age is Bristol. A walk around any of them reveals the majority of people who tend to get memorialised are colonial tyrants, slave traders. Maybe the lack of statues of critics (and most musicians) is a good thing. It’s only right that the ritual of the live concert should see the musician worshipped, temporarily, as some kind of god… all of that effort and inspiration, cultural risk taking and thrilling spectacle deserves payback. But once you leave the theatre? Statues? I’m not so sure. In 1996 a 20ft tall statue of Michael Jackson was erected on the Letna Hill Stalin monument plinth to promote the start of the HIStory tour but it didn’t last long. Perhaps when we tear down and dynamite all statues we will be able to consider ourselves fully advanced. Traces of the Indus Valley Civilisation were only discovered a century ago because of its near total lack of monumentalism. It seems they didn’t really have statues – of the handful that have been found, the most notable two are of unnamed dancers – yet they invented the house brick as we know it today; they had the city grid system; their kids had toys; there’s evidence of flushing toilets. They even had boardgames for God’s sake. Over five thousand years ago.

The thing is however that Charli XCX probably wasn’t being entirely serious.

The thing that everyone in Prague wants to talk to me about is how music journalism has become defanged. How everything is now awarded three or four stars out of five. How literally everyone who makes music and makes money at it has become a sacred cow. Charli XCX is a highly inspirational figure in that she makes me ask, ‘Where actually are the critics?’ None of us should even be allowed to call ourselves critics, let alone worry about statues, if we aren’t willing to criticise the apparently uncriticisable.

The detail, shared across social media in January, that Global Chief Content Officer of Conde Nast, Anna Wintour, wore shades while sacking scores of Pitchfork staffers, soon after it was announced the music magazine would be merged with GQ, caused understandable knee-jerk outrage.

“Anna Wintour’s sunglasses are a dead cat”, I say. And then mindful of the pie in the sky imagery I add: “Do you have dead cats in the Czech Republic?” Just to have a room full of people nod at me. Of course they have dead cats, you idiot! I think to myself. The world is now full of dead cats. “There’s a saying in business which goes, ‘You can be rich or you can be king, but you can’t be both.’ Pitchfork was sold in October 2015 by people who wanted to be rich, and to anyone thinking, ‘Well, it was fine at first’, I’d remind you that on the actual day of purchase, Fred Santarpia, the Conde Nast Chief Digital Officer, responsible for the deal said that it had brought ‘a very passionate audience of millennial males into our roster’, revealing that things were very far from fine from the outset.

“When someone decides to shoot you, a series of linked events happens. After seeing you, a primary decision is taken by the shooter, the weapon is aimed, and the decision becomes action when the trigger is squeezed. The firing pin strikes a small charge in the projectile, the resultant explosion superheats gas in the barrel behind the round forcing it, at speed, out of the gun. From your point of view the events happen in this order: there is a flash of light, the bullet hits you and, if you are still conscious, some time later, there is a loud noise. Fred Santarpia buying Pitchfork is the finger squeezing the trigger, Anna Wintour, the noise you hear later.

“I think there’s only one hope for us” – and by us, I mean all of the writers, editors and photographers, artists and so on in the room – “and that’s for us to maintain ownership of what we write and what we create. And it doesn’t really matter to me so much what you want to call that.”

My mind is temporarily warped when I look up from all of this pontificating and see, in the audience, a hip youngish guy with a Merzbow T-shirt and a large tattoo on his forearm of Anna Wintour wearing sunglasses. I have just enough time to think, “I’m in a computer simulation!” before I realise with great relief that the tattoo is actually the sleeve of Les Rallizes Denudes’ Heavier Than A Death In The Family LP. The youngish guy who owns the tattoo is Andrej Kabal and his brand new darkwave techno duo Kabal & Aras play sumptuous moody bangers in support of a very powerful set of new material by Marie Davidson at the same venue later that evening.

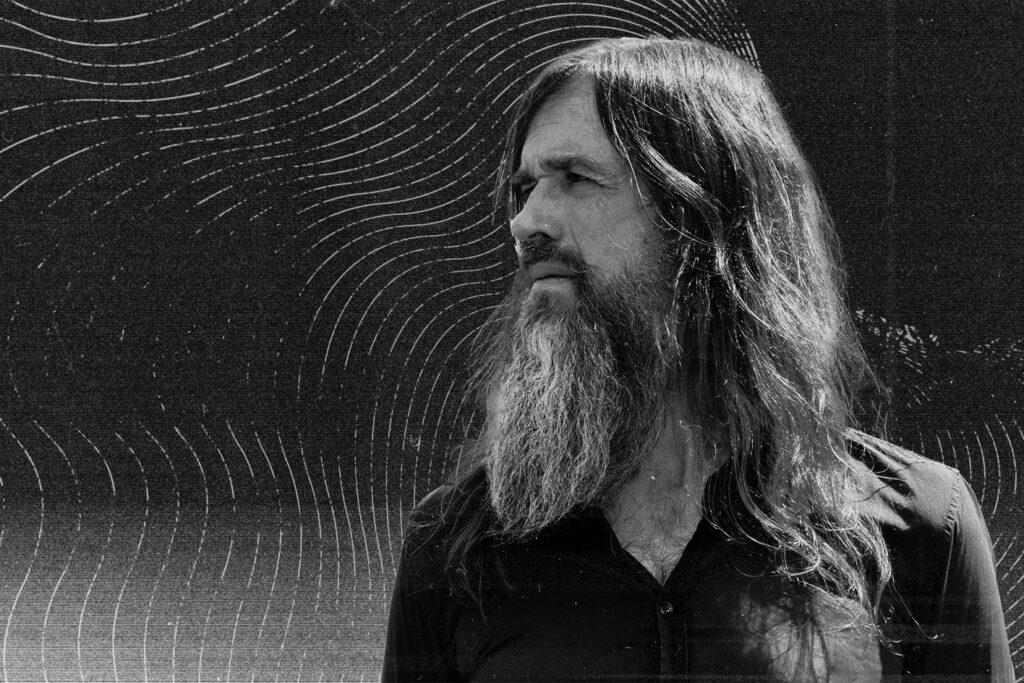

The next day Sapphire and I present our What Is This That Stands Before Me: Heavy Metal And Modernism live documentary performance on a bill that includes the newly re-engergised Chelsea Wolfe and Icelandic synth goth Kælan Mikla.

To get to the venue you have to walk down a partially deserted looking slip road past a graveyard-like lot full of old train stock, some decorated with striking decals. Someone later tells me that they are used in Czech film and TV: “The trains are from the 1940s but the Nazi logos are new.”

The entrance to the former glass factory is guarded by a very fine-looking parrot called Potato who only looks shy when she is being filmed. The imposing building is literally on the wrong side of the tracks – there are countless signs pleading with gig goers not to take the potentially fatal shortcut back to town across the train lines – on one side and under a busy flyover on the other.

It’s a pleasure to meet the guy behind it, Václav Havelka. We bond over the fact that we both got into The Fall after repetitively listening to a tape of the John Peel show during 1984… but of course, the means by which we acquired our tapes of the John Peel show during 1984 were remarkably different. As he shows me around the gig rooms, theatre space and artist workshops I start getting a really positive vibe. “I can imagine Mike Watt playing here!” I say as this has become a kind of unconscious universal measurement for me, wherever I go; a way of taking the cultural temperature of DIY venues in terms of their ability to withstand the odds stacked against them, beset as they are by both local and international pressures. Vaclav laughs and hands me a CD, “My son and I just did an album with Mike on it. And Thor Harris. And Paul Leary.” But of course. He actually has plenty of musical projects. What an incredible place. And they’ve made really nice food for us. The show itself is packed. Afterwards the unblinking young man doesn’t hang around to talk but loads of other people do, suggesting that people with his brand of internet-curdled philosophy are an anomaly in such forward looking venues as MeetFactory, Ankali and Planeta Za and the local underground culture they service.

The next day my flight home is quite late so I just potter about Prague in the sunshine. In the books and vinyl paradise that is Rekomando I meet Judita Císařová a local punk musician, promoter, radio presenter and general powerhouse who works on local shows with visiting bands from labels like La Vida Es Un Mus and Static Shock.

It’s such a shot in the arm to be in Prague. I tend to sit on my own at a laptop all day, my interactions with nearly everyone mediated by the insanity of social media, the mither of DMs or the mardy faux-civility of email. I’ve had more dynamic conversations with people about the need for good outlets for music journalism and the health of DIY culture in general in the last three days than I’d had in the previous three months. It’s been a much needed corrective to my own dourness about the ongoing negative impact of Covid: in 2024 new networks are being formed and old ones are being repaired and improved. New pathways to new weird everywhere being trodden once more.

Nearly every street I walk down has a different assembly of cobbles or small stone flags, arranged in different patterns, so with every corner turned, I’m given a new rhythm track to walk to as the wheels of my flightcase rattle along the floor. Seriously, the opportunity just to go to a different city and listen, is such a luxury.