There tends to be only incidental conversation between so-called academic and popular music. And this persists despite good faith efforts by recent generations to chip away at the barriers (on either side of the divide). A few influential composers have crossed over from "serious" contemporary classical music, and are now commonly cited as touchstones in rock, pop, and electronica. But across the board, their broader appeal seems driven by the accessibility of their musical language: from veteran voices that are culturally ingrained (Steve Reich, Arvo Pärt) to those just emerging as forces in their own right (Du Yun, Missy Mazzoli).

Occasionally, however, this unwritten rule is broken. And no case is stranger than that of Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001), one of the most prolific composers name-checked as inspiration to those beyond the ivory tower. Xenakis was an uncompromising avant-gardist, whose dense and esoteric approaches to sound design still today conjure awe. Yet his devotees run the gamut, from Henry Rollins to Lou Reed; from Nurse with Wound to Merzbow; and from Matmos to DJ Spooky, to name only a few. Noise junkies, psych rockers, punks, rivetheads, EBM fetishists, goths, black metal knights: they all bow down at the altar of this high priest of High Modernism, awkwardly christened "the Trent Reznor of contemporary classical" by SPIN. Xenakis’s trademark sound – pioneered in the 50s but never stagnant – harnesses statistical probabilities and mathematical games to realise pieces that are simultaneously creeping and sublime. They evoke a writhing, ripping, or swarming affect, and often seem immense, cosmic and otherworldly. And this became a sonic template for Xenakis’s followers outside of academia; his aesthetic seems to have wormed its way in, consciously or not, to the DNA of loud, extreme, and provocative music over the past five decades. I want to explore Xenakis’s weird celebrity in music subculture by looking at both the webs of influence that fans and critics place him in, as well as the conversations that circulate about his style. But there is a flipside to explaining Xenakis’s notoriety. How is Xenakis’s fame so outsized, when composer contemporaries like Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016) remain relatively unknown, despite having instigated many similar currents that we today take for granted in rock, pop, and electronica?

In December 1994 Xenakis premiered S.709, his final piece of computer-generated music. This shredding cacophony arrived on the tail end of a nearly half-century career, one that first began with iconoclastic instrumental works like Metastaseis (1954) and Pithoprakta (1956), as well as early electronic collage pieces like Bohor (1962). But listening to S.709 in the context of the early 1990s feels odd, because by this point, Xenakis’ sound world – a grinding, atomized maelstrom – is no longer rare or unique in a market increasingly saturated by sludge, grunge, noise, and industrial music. Come 1994, the so-called third wave industrial bands like Godflesh, Marilyn Manson, KMFDM and Nine Inch Nails are enjoying breakthrough success, with most notably The Downward Spiral going quadruple platinum and becoming a critical darling. And so Xenakis’s music comes across as almost quaint in the twilight of his career.

For the "Xenakian" sound to reach mass audiences in the early 90s, a roundabout journey of cultural transmission took place, lasting nearly two decades. According to music critic lore, the first Xenakis crossovers are heard openly on projects such as Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music (1975), and Reed did indeed

namedrop Xenakis in interviews. Metal Machine Music is frequently held up as a lodestar for the industrial sound and scene, but industrial artists and other sonic rebels also had plenty of direct access to Xenakis’s music. For instance, Xenakis gets linked to the clangorous spirit of Einstürzende Neubauten and Blixa Bargeld; the

dystopian performances of Survival Research Laboratories and Whitehouse; and the "Japanoise" subculture, through groups such as Merzbow or Hijokaidan. Xenakis receives prominent billing on the infamous "Nurse With Wound List," which functioned as a pre-Internet "primer" to the source code of industrial culture. And the always-provocative Steve Albini even draws a circle around Xenakis with the likes of Cabaret Voltaire, SPK, and Deutsch Amerikanische Freundschaft. Music historian Alex Reed (no relation to Lou) summarizes this mood: "There’s a vague but deep gut feeling… that a hidden truth about industrial music lurks in the [oeuvre] of… Iannis Xenakis" (Assimilate). But others like critic Kev Nickells contest this as a bit overblown: "[Xenakis] is definitely a post-Internet ‘huge influence’ on noise and industrial, but I remember very clearly ’90s industrialists having minimal idea about Whitehouse and TG [Throbbing Gristle], let alone electro-acoustic folk like Xenakis…" (Freq).

Xenakis also holds sway in the quirky corners of 2010s popular music, but with more diffuse points of entry than the Baby Boomer or Gen X artists named above. Sometimes, programming choices speak volumes – see Zola Jesus’ recent curatorial outing where Xenakis works were featured. Elsewhere there is hazy transference across generations. For instance, Pharmakon channels Diamanda Galás, who is herself a famed Xenakis interpreter and evangelist. Xenakis goes unnamed in Pharmakon’s public statements, but the dissolving textures associated with his sound are all-too recognisable. And this "degrees of separation" game also likely connects similar kindred spirits to Xenakis, such as Wolf Eyes, Prurient, Lightning Bolt, or Fuck Buttons. Contemporary artists are occasionally placed in the Xenakis family tree by critics – for instance, profiles of Haxan Cloak, Oneohtrix Point Never, Relaxer, or Scott Walker. Still others insert themselves, while extolling their high art bona fides to interviewers – check out conversations with Jute Gyte, Stephen O’Malley/SunnO))), Liturgy, Imaginary Forces, Russell Haswell/Pain Jerk, and perhaps surprisingly, the sludge metal trio Brainoil. And today, artists more diverse (in both style and identity) than the early industrial kids see themselves traveling in the wake of Xenakis, from jazz pianist and composer Craig Taborn, to Battles’ Tyondai Braxton, to electronic musician Ash Koosha.

The musical underground borrowed Xenakis’s sound far more readily than his own peers, and he inadvertently provided early access to high art styles for the tinkerers working on the cultural fringe of the 70s and 80s. This predates (by more than 30 years) the chic, grant-funded, and antiseptic collaborations that have recently proliferated, where Johnny Greenwood, or members of Wilco, The National, et al moonlight with a chamber group or orchestra. But while Xenakis’s sizable impact on subculture is plainly seen and felt, the larger conversation that surrounds his music is also bizarre and overwrought. So much so, I think this breathless discourse – by both classical and pop/rock critics – not only does a disservice to the artist and his creations, but also muffles the reception of his fellow travellers who made similarly remarkable contributions to popular styles and techniques.

A quick survey: WQXR-FM radio exclaims Xenakis brilliant, with "a cultish following" and "rabid devotion." The Los Angeles Times christens Xenakis "a new music rock star" and "avant-garde superhero" whose "ultra-complex" pieces require a working knowledge of calculus, architecture, ancient Greek music theory, and computer programming to appreciate properly. Furthermore, "if you’re not tough, forget it…. angry dissonances threaten…. Luddites, lightweights, wimps, and most of all sentimentalists [should] stay home," since they cannot grapple with "a composer with so steely an intellect… one who wrote music of such shockingly cold, hard power…" Slate situates Xenakis in the lineage of "aesthetic brutalism" whose descendants "have a background in heavy metal or punk… [with] an often ahistorical sensibility formed in a riotous milieu." Indeed, as a brutalist, Xenakis "does not aspire to move you; [he] wants to hurt you." And The Guardian exalts Xenakis’s "elemental music" with "scintillating physicality," that "[turns] instruments into a force of nature, releasing a power" with "arguably greater clarity, ferocity, and intensity than any musician, before or since…" Pitchfork says we hear "… a totally unhinged and massive wall… vast tidal arcs of quivering… a totally mammoth and inhuman mindfuck… [deserving] caution and respect." The Chicago Reader cites Xenakis as the progenitor of "noise, hard noise, industrial noise, power electronics, and no wave," and by comparison to Xenakis, Merzbow "sound[s] like refrigerator hum." It goes on.

Both classical and pop/rock tastemakers portray Xenakis like some sorcerer of antiquity, able to thin the veil and conjure vengeful demigods from a plane beyond our ken. But for these commentators, Xenakis’s dangerous charms come not from spellcraft, but rather, a technocratic proficiency in STEM fields, design philosophy, and musical mechanics – closer to a TED Talk than a fearsome wizard. More problematic, however, is their consistent choice to frame Xenakis using pernicious (and in this context, slightly comical) tropes of masculinity: for instance, the toxic conflation of physical intensity, emotional detachment and intellectual "rigour"; the implied desire for sound – and by extension, the composer’s "genius" – to dominate and annihilate the listener; and the disparagement of intuition, curiosity, or care as evidence of a feeble character and brittle artistry, easily bent or broken. These critics caricature him as a quintessential masculine id; just Conan the Barbarian, reincarnated as composer. And here is precisely where other creative voices, who work in parallel spaces as Xenakis, are suppressed if their musical aesthetics fail to sync up with this cartoonish "will to power" rhetoric that has taken root. Stereogum’s essay on the Nurse With Wound List smartly notes that "… with 40 years of hindsight it’s evident that… [the List] could use Pauline Oliveros…"–a recognition of the latent prejudice behind those canonised (or not) in early industrial culture. But Oliveros’ exclusion then is a telling segue to Oliveros’ exclusion now, since she receives far less thanXenakis’ esteem from subculture critics, artists, and fans; despite having contributed as many, if not more stylistic and technical inventions to the musical underground. I think Xenakis and Oliveros are particularly connected, not only for their scale of innovation, but in their profound explorations of ecological and spatial concepts through art. Phrases describing Oliveros’ music do seem to resonate with Xenakis fandom at first blush. Her sounds evoke "comprehension of an ancient secret"; "intelligences from the furthermost realms… the chthonic, the galactic, the electromagnetic"; "a mutating opus… unnerving, eerie, even chilling occasionally" (New York Times); and "phantom psychoacoustic melodies… of epic proportions" (San Francisco Classical Voice).

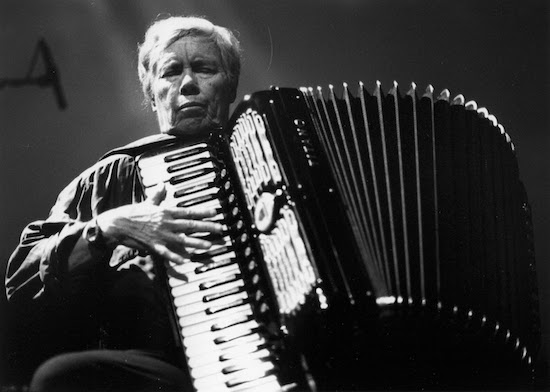

Yet whereas Xenakis sought to apply complex formulas to emulate the stochastic rumblings of the natural world (human agency be damned), Oliveros sought similar affects from an opposite angle. To tap into these ecological systems, she privileged the very intuition, vulnerability, and receptivity to our surroundings that Xenakis’s superfans find so mewling and weak. As a queer woman Oliveros struggled against prejudice from both the music industry and ivory tower of academia during her most productive years, dampening the reception to her work during her lifetime. Titans of the musical avant-garde such as John Cage and Philip Glass cited her incessantly as inspiration, yet even as their stars rose, Oliveros remained relatively obscure. And only in the past three years since her death in 2016 have critics and curious listeners started to process the far-reaching, sometimes subtle ripples that she began in our culture. Her name now occasionally earns billing alongside Reich and Glass as a pivotal 60s American minimalist, whose collective movement influenced hundreds of popular artists and dozens of genres. Oliveros and other nonconforming composers/creators are rarely afforded the presumption of seriousness as artists. Yet arguably neither she, nor today’s kindred musicians working from the margins, require this external permission or validation – thanks in part to her trailblazing career. As Russell E.L. Butler and The Black Madonna note, for them, Oliveros is not only a founding mother of electronic music, but a beacon for artists who feel "cut out from [the] history" of the avant-garde: "Pauline is just so fundamental… she’s an element. She’s massive", as The Black Madonna told The Vinyl Factory.

Just how massive? Before the guitar pedal craze; before Frippertronics, or Tangerine Dream; and a decade prior to Brian Eno’s Discreet Music (1975) and Music for Airports (1978), Oliveros pioneered a real-time signal processing setup which she christened the "Expanded Instrument System," or EIS. As first heard on landmark pieces like Bye Bye Butterfly (1965), the EIS array fed sounds through sequentially connected effect units (reverb, echo, looping) which the artist then manipulates live. Oliveros is arguably the originator of this tape delay aesthetic, which radically altered not only an artists’ relationship to their technologies and sounds, but the nature of musical performance itself. In fact, this approach is now so foundational and ubiquitous in electronica, rock, and pop, it’s practically transparent to our ears. Some are recognizing the seismic influence of Oliveros’s EIS, but she is still largely invisible in the folk histories of the musical underground. This fact is even more extraordinary since her musical techniques are today so widely adopted, whereas Xenakis’s were (intentionally) anything but accessible.

The lost reception of Oliveros’s Deep Listening method is a second telling example. Like Xenakis, she sought to evoke the colors and textures of the natural world. But rather than mimic its inexorable and unrestrained chaos, Oliveros found revelation in the collage of murmurings and pulsings that envelop us in mundane life. She cited as inspiration the half-heard, ephemeral chittering of bugs and birds in rural Texas during her childhood; radio static on the dial between stations; and underground cisterns of pooling water. From these sources, Oliveros developed Deep Listening as an approach to both personal introspection and musical composition, formally laid out in her "manual" Sonic Meditations (1974). Her Deep Listening pieces – such as Big Mother Is Watching You (1966), or To Valerie Solanas And Marilyn Monroe In Recognition Of Their Desperation (1970) – were carefully designed to weave environmental ambiences into the work’s larger tapestry; encourage both performers and listeners to engage with a space’s subtle sonic contours; and explore larger social and political ideas coded in the sound. This aesthetic is clearly a wellspring for much electronica we hear today, particularly the IDM that explores a gauzy patina, glitchy rumble, or lo-fi affect. Aphex Twin’s ambient style, Burial, Andy Stott, Jon Hopkins, Four Tet, Boards of Canada and on the dark end, Lustmord and later Coil, all absorb and re-translate these themes with their own thumbprint. Among these artists, we hear Deep Listening as an unsettled thrumming on the edge of perception; a displaced agency, alternately human and haunted; or a blurred emotive energy that tenses and unwinds in the cavernous sonic backdrop.

Xenakis and Oliveros were two composers whose imaginations surpassed the prevailing dogmas of late 20th-century classical music. But rather than remain walled off as curios, experimenters from diverse corners of the musical underground borrowed their methods and affects, to kick-start genre sounds nothing less than iconic to our ears today. And so, weirdly enough, Oliveros and Xenakis’s legacies are more profoundly heard and felt, I think, in music subcultures than among any fellow composers, then or now.

Yet despite their similar paths, and status as artistic peers, each clearly encountered different headwinds upon crossing over from academia. Xenakis is cheered as a godfather of outsider music, and worshipful critics and fans are only too eager to connect the dots from his difficult style to today’s buzz bands. Simultaneously, Oliveros is more or less a blip in those same narratives; a fact made stranger since in recent years more left-field events such as CTM in Berlin, London’s LongPlayer and LCMF or Knoxville’s Big Ears have hosted performances and lectures related to her work. But unlike Xenakis – himself the focus of many heady symposia and retrospectives – that just hasn’t yet translated into some of the more commercially successful acts or tastemakers who borrow Oliveros’s ideas actually naming her as a touchstone, centring her in scene histories, or recognising her stylistic innovations. She remains merely nodded at by major institutions.

This circumstance is precisely because the chatter surrounding Xenakis’s legacy polices how a real composer is supposed to think or feel about the world in order to be judged compelling. Even though Oliveros possessed all the right stuff to be recognised as a sensation on the scale of Glass or Reich, her musical questions around care, egalitarian power, and self-experimentation simply don’t conform to the preferred (and fictional) artist personality of composer-conqueror-sociopath that has been posthumously foisted on Xenakis. In fact, her questions seem designed as antidotes to this poisonous hype that the critics finds so persuasive; and let’s hope they work. Oliveros’ story is only the most immediate one; over the decades, no doubt many other radical voices have been marginalised because they failed to fit this desired mould. But in the short term, celebrating her as a godmother of popular scenes, with the same stature as Xenakis, will show that Deep Listening is still subtle, but always working.