Last weekend, I watched as much as I could stomach of Kilkenny and Offaly in the first round of the Leinster senior hurling championship. The game was significant, not for the sickeningly high score Kilkenny posted, but for the fact that it was broadcast on Sky Sports. In this respect, the game was the first of its kind. The entry of Sky into the GAA market is a turning point for an organisation that defines itself by being intensely local. It is also a sign that, as far as the Murdoch empire’s rapacious appetite for new content goes, there is no end in sight. Having conquered the big games, niche markets are all that’s left.

Will the deal with Sky be good for the game? It’s probably too early to tell yet. It’d be foolish to believe there won’t be some concrete benefits trickling down the ladder but still, it’s hard to get past the image of Sky as a behemoth only interested in the game for the targeted advertising and passionate demographic, lacking the authenticity of the state broadcaster which has, at the very least, put in the hours. There are bigger questions still about the conflict between a multi-million euro television deal that makes the audience pay to watch, and the players’ amateur status. (In the world of the GAA, no player gets paid – you do it for passion alone.)

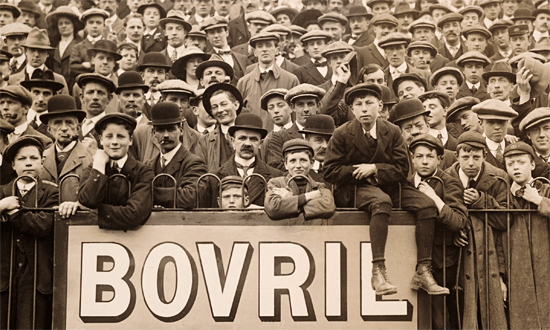

A few weeks before that game, I went to see Pat Collins’ new film, Living In A Coded Land, in the IFI. The film is about community in an almost abstract sense, focused mostly on the midlands of Ireland. What makes a community? What ties people together? What happens when a community falls apart? What is lost? These are big questions and Collins is smart enough not to offer platitudinous answers. One of the more surprising elements of the film was the recurring images of a hurling game. The pictures of the crowd on a summer’s day, much like last Saturday evening, whether watching Kilkenny in Nowlan Park or the local team down the road, are dreamlike. They seem to say, this is where it happens — community spirit in action, an untainted space. An American voiceover talks about the need to engage with people on their own terms, taking them as you find them, and trying to understand and appreciate their customs through their eyes rather than your own.

It’s not so much the point that’s being made that is strange – anybody in rural Ireland will tell you how important sport is to a community – but where it’s being made. It’s not often that you find experimental filmmakers, or artists of any ilk, using sport as a positive element within their work, never mind holding it up as an important cornerstone of communal solidarity. More often, sport is something the artist reacts against, something they feel closed off from, something to which their strengths are less than suited.

This is a feeling I’ve had a few times in the past few weeks, when I had occasion to interview a few musicians, mostly friends of mine, about their backgrounds in farming. One of the threads I found running through most, if not all, of the conversations was these artists’ respective interests in music developing in opposition to, or as a reaction to, the more general interest in sport they saw around them. Where their small rural communities were focused on hurling or football, they felt themselves to be outsiders because they were instead interested in music and art; a different kind of creativity. The relationship between sport and art was antagonistic, impossible to resolve.

In this common formulation, sport is often seen as boneheaded, overly masculine, regressive. The money that swills around professional sports is seen as distasteful, if not outright disgraceful and morally indefensible. Art is an antidote to this, the pure expression of emotions and ideas, an activity that requires a certain, more widely acknowledged, form of intelligence. It is a deeper sort of exchange. It also helps that you generally don’t have to work up a sweat or face the prospect of injury while making music or painting.

This formulation is, of course, utter bollocks. Art and sport are not at opposite ends of the spectrum of human activity. One is not more intelligent, creative and positive than the other. In fact, they share some key aspects, both negative and positive. The money involved in the professional end of some sport is indeed disgusting, but so is the money involved with art at the "highest" level. If Jeff Koons can make millions from his sculptures, why shouldn’t a footballer get paid £300,000 a week? If a single Picasso sells for €100m, should Gareth Bale not sell for the same? At least Gareth Bale lives and breathes. In all professional sports, big clubs pick off the best young players from smaller clubs and the hierarchies of power remain, for the most part, quite static. But do large galleries, publishers and record labels not do exactly the same? Industry is industry. Money taints both sides equally and it has a logic all its own.

Another commonality is the widespread ability of fans to wilfully ignore, or go to great lengths to justify, actions that might, to someone else, appear deplorable. This is as true for a fan of GG Allin or Lady Gaga as it is for a Chelsea or Manchester City supporter. Sometimes the people we love do detestable things and we love them anyway; we can’t help it. This most dangerous trait has been at the centre of debates about the nature of this year’s Fifa World Cup, and indeed the next two World Cups. This year’s tournament, as I’m sure you probably know, is in Brazil. Many Brazilians are less than happy that billions of dollars have been spent on tournament infrastructure such as stadia and special tourist bus routes, rather than, say, housing or healthcare or buses for normal people. The deaths of workers involved in building this infrastructure has also caused justified outrage, sparking protests on the streets in several cities. Protestors then, in turn, are shot and injured or killed by an increasingly militant police force, leading to more protests. As a distant spectator, reconciling one’s love for football played at the highest level and one’s concern for the exploitation of the working poor in a developing country is no easy thing. For ninety minutes at a time, I know I won’t care. But the rest of the time, I’m sick to my stomach, as angry with myself as I am with FIFA or the Brazilian government.

If the situation in Brazil is bad, then the one in Qatar is worse. With eight years to go until it is due to host the tournament, over 1000 workers have already died in the construction of stadiums. There have been several dogged problems, from concerns over player welfare that might cause the tournament to be played in winter, to concerns for the safety of women and the LGBT community at such a tournament. Then the big scandals; the practical slave-status of workers, usually migrant workers, who are building the infrastructure. They have their passports taken from them, often going unpaid and over-worked in terrifying desert heat. They are utterly powerless and their deaths appear inconsequential to those in charge.

If this violation of basic human rights was somewhat surprising, in scale if nothing else, then the accusations of bribery and corruption were less so. The current investigation as to whether several FIFA delegates were paid to vote for Qatar ahead of other potential hosts came as a shock to precisely no-one. FIFA tends to exist in a cloud of continuous suspicion and does little to dispel this distrust. (In all the furore about Brazil and Qatar, Russia – host of the 2018 World Cup – seems to be getting off lightly, so far at least, though one FIFA official’s assertion that antidemocratic leaders like Putin make World Cups easier to organise is bound to blow up in someone’s face.)

But, just as the good church-going folk don’t elect the pope, nobody playing Sunday league is voting for the sport’s governing body. Indeed, not even the well-remunerated players who’ll be appearing in Brazil this week have any power over who runs their game. There is a total disconnect between the structures of the game – the governing bodies, the broadcasters, the sponsors, the big business side – and the players and fans who make it the most popular game on earth. How do we reconcile the two perspectives into a single view? How can we balance despising the runners of the game, with love for and solidarity with those who play and support it, those who keep it alive? How do we bridge the gap and agitate for change? What does the "action" in "community in action" mean for us here?

Football, and sport in general, has always been used to expose and give form to local rivalries, from neighbouring parishes to national or post-colonial concerns. For better or for worse, it has always made concrete the ephemera of political tensions. This is where sport begins to complement artistic endeavour, rather than match or oppose it. Where successful art generally approaches the political obliquely, with allusion more than direct confrontation, sport revels in pure representation; the scale model. The World Cup offers the opportunity to see how the whole world works, condensed into six summer weeks of quality entertainment in Brazil. Exploitation of workers and national resources, violent police crackdowns on dissent, a tax-dodging multinational running the show and, in the middle of all the shit, something glorious, beautiful and unexplainable.

The World Cup is also as close to a moment of global "community in action" as we’re going to get in this stratified world, even if that action is just staring at a television. The minds of billions bend toward the same place and time—the same concerns on their faces, the same shocks of awe and wonder. If all those minds got behind the battered protestors on the streets of Rio and Brasilia, then change would come soon enough. And if change can come in football, it can come anywhere, because football is everywhere. It’s probably not going to happen, but I’m sure I’m not alone in thinking there’s great hope to be found there all the same.