In Wim Wenders’ 1974 road movie Alice In The Cities, we first meet Philip Winter sitting under a boardwalk, camera in hand, as he stares out to sea. The West German journalist has been assigned to write a story about America, but as he drives along its eastern coast, stopping at dusty gas stations and neon-lit motels, he seems immobilised by the enormity of the task, unable to articulate himself. At a loss for words, he turns to instant images, using Polaroid film to document his experience. Even this seems inadequate; the pictures never truly show him what he’s seen.

There is something about Wenders’ ode to the transience of the Polaroid format that made me think about my own camera. “Photographs are perhaps the most mysterious of all the objects that make up, and thicken, the environment we recognise as modern,” Susan Sontag wrote in a collection of essays entitled On Photography, published in 1977, three years after Wenders’ film was released. To take Sontag’s assertion one step further, perhaps instant photography is the most mysterious of them all. At once temporal and ageless, the mechanical click and the purr of the motor seem to offer an exactitude in spite of the camera’s shortcomings. Then there are the images themselves: as capricious as a piece of pottery going into the kiln. Which, as many a Polaroid-enthusiast will attest, is where the fun really kicks in, because you never know what shot you’re going to get. Maybe that’s where the crux of my enthusiasm for these quilting squares can be found: in a state of uncertainty which, for me at least, brings with it a certain kind of childlike wonder.

For Wenders, “the meaning of these Polaroids is not in the photos themselves,” but “in the stories that lead to them.” I read these words in an old interview with the filmmaker not long after I got to the closing credits of his hazy portrayal of a drifting writer. In doing so, I realised that the fictional Winter’s complicated feelings towards the Polaroids he takes are really Wenders’ own. The filmmaker took around 12,000 Polaroids in the decade between 1973 and 1983. Like his films, these pictures were, he told his interviewer, “made from the gut.” It’s an interesting phrase to use when you consider its etymological roots: from the Old English ġēotan “to pour” – a verb used to endow his Polaroids with a liquidised quality that seems in keeping with their ephemerality.

Wenders was given his first Polaroid camera by his father when he was a child living in post-war Düsseldorf. Was the city’s near-total devastation during WWII and frantic reconstruction over the course of his childhood somehow connected to his fascination with these fragile frames of plastic, emulsion, and chemicals, ignited by light? “They are a healthy memory of how things were and what we have lost,” he said of these photographs. My camera was also a gift, a 90s Polaroid 600 Extreme bought for me by my late husband in the noughties. It’s a cumbersome thing with a box-like shape that gives it the appearance of a toy. Specifically, in the case of my own, a jack-in-the-box that I treasured as a child, with its volatile crank, going round and round, until a clown burst up from beneath its lid. You could argue that this is an apt metaphor for the quirks of the Polaroid; an offshoot from an already erratic form of image-making that Sontag said was as close to ‘true’ surrealism as art was likely to get. It’s a practice that, she claimed, “has always courted accidents, welcomed the uninvited, flattered disorderly presences. What could be more surreal than an object which virtually produces itself, and with a minimal effort?”

I dug out my Polaroid this summer before embarking on the same road trip that Wenders had fictionalised five decades earlier. Like Winter, my boyfriend and I were about to drive the 600-odd miles from North Carolina to New York, only in reverse: taking us from my friend Miles’ stoop in Brooklyn, into the industrialised headland of New Jersey, before wending down into the verdant pasture of Virginia. From there, we would travel further south to the North Carolina town of Chapel Hill, home to Merge Records, where my boyfriend’s band, The Clientele, were playing at a four-day festival to mark the label’s anniversary. At the age of 41, I had yet to experience the promise of the oft-mythologised American road. I suppose that this mythology had something to do with my decision to take my dilapidated camera with me, as I challenged myself to take a Polaroid a day in order to document the trip in a way that I perceived – either rightly or wrongly – that my iPhone couldn’t.

In part, this challenge was also inspired by the New York-based photographer Jamie Livingston. Between 31 March in 1979 and 25 October 1997, the day of his death, he took a single picture every day with his Polaroid SX-70. His project had only one rule: there would be “no do-overs”. Over a period of eighteen years, Livingston took 6,783 Polaroids in sequence. Nearly thirty years on, his scrapbook is continuing to amass a cult following, drawing fans to what his friend Hugh Crawford called its “everyman quality”. Most of these snapshots – 86 have gone missing – can now be viewed, in parallel chronology, on the Polaroid’s digital successor, the photo-sharing platform Instagram, where his family continues to post his candid images of Ritz Crackers boxes, cigarette lighters, and fields of sunflowers, with occasional jolts that document a malignancy in flux. Livingston, like my late husband, died of a brain tumour at the age of 41, a convergence that only became apparent to me during the writing of this essay. Looking at him bandaged in a hospital bed brought me back to the memoir I wrote of my grief in 2021, when I made reference to Sontag’s theory that all photographs are a kind of memento mori, a slicing and freezing of time. This was a tenet shared by Jacques Derrida – so much so, that he rejected his own image altogether, forbidding the publication of any photographs of himself until 1979. “I don’t like the death effect, so to speak,” he part-explained in a far more complex interview that you can watch on YouTube. “The kind of death that’s always implied when one takes a picture.”

In 2008, the performance artist Lynette Astaire tapped into this subtext of loss and mortality when she processed, New Orleans style, through the streets of New York for a photography piece that she called Polaroid Funeral. This was a far cry from the Polaroid’s creation, sixty years earlier, when the inventor and physicist Edwin Herbert Land was challenged to conquer time itself by his three-year-old daughter on a holiday in Santa Fe. Maybe the subtext of loss and mortality was there from the very beginning. Why couldn’t she see the picture now, Land’s daughter asked her father as he snapped away with his Rolleiflex. It was a question he couldn’t answer. Although Land had already co-founded a commercial lab in 1932 and renamed it the Polaroid Corporation in 1937, his discovery, at the age of just nineteen, of a synthetic polarizer (microscopic crystals of iodoquinine sulphate embedded in a transparent polymer film) had primarily been used to provide military equipment – including filters for gunsights, binoculars, periscopes, and infra-red night viewing devices – for the armed forces during World War Two. Now he was being challenged to create an instantaneous device that, like his sluggish Rolleiflex, could, as the art critic John Berger later wrote about photography at large, “contribute to a living memory”.

Four years later, in 1947, Land gave the first public demonstration of his new Polaroid Land Camera which, as Christopher Bonanos writes in Instant: The Story Of Polaroid, “was like replacing a messenger on horseback with your first telephone”. What followed would propel Polaroid from brand to noun itself. Even now, we don’t take instant photographs, we simply take Polaroids. As Bonanos puts it: “Throughout its reign over instant photography – a field the company invented out of thin air and built into a $2-billion-a-year business – Polaroid had no successful competitor, no real challenge to its primacy, until almost its very end.” Likewise the process has largely stayed the same, too. “After the exposure of a film, a “sandwich” of positive and negative sheets [is] moved through a set of rollers on its way out of the camera, either pulled by the photographer or ejected mechanically,” wrote Peter Buse, author of The Camera Does The Rest; “The rollers burst a ‘pod’ of developing reagent attached to the film and spread the contents of that pod thinly across the film to set the development going.” Even this simplified explainer baffles me somewhat, like a Rubik’s Cube I’ll never be able to complete.

Maybe Bonano was right when he mused that instant photography “seems to exist in the realm not of science but of magic”. There is an intimate symbiosis that can be felt when that alchemy takes place in those ten to fifteen minutes of developing time, like a secret liaison between photographer and camera as ghost-grey silhouettes shapeshift into dawning outlines of blues, greens, and reds. A “happening” in real-time that evokes a certain vulnerability, too. As many have stated before me, every Polaroid is an edition of one, something that Buse reflected, “can only add to their perceived fragility”. I sensed that fragility every day on the road as I anxiously stored my glossy squares in the hot confines of our rented car, wholly convinced that the hydroquinone dye would melt into a inky pool on the dashboard. This, when I look at them now, only adds to their greater sense of preciousness and exceptionality. I took many sharper focused and better exposed images on my iPhone, yet the few flawed photographs I captured with my Polaroid feel more prized somehow. Not only a fragile memento of time and place, but of the people who accompanied me on this brief journey, too. Take my most treasured, the only Polaroid I chose not to take myself, a souvenir that marks the sweltering day my boyfriend drove me all the way to a railway station in north Virginia to recreate my favourite Stephen Stills album cover from 1972. The second it was taken, it became a talisman to that moment, and that instinctive gesture, in ways that its digital successor never could.

“If a toy comes with no specific instructions for use, the only option is to try things out,” Buse writes of the Polaroid’s playful invitation to experiment – something I leaned into with gusto on our trip. But since Polaroid’s invention, it’s what artists have always done, encouraged by the company’s founders themselves. In the 1950s, they began collaborating with landscape photographers like Paul Caponigro and Ansel Adams, supplying them with Polaroid film in exchange for pictures and consultation. Which is how the world was gifted with Adams’ magnificent portrait of pine, stone, and mist, ‘El Capitan, Sunrise, Winter, Yosemite National Park, 1968’, proclaimed by Bonanos as “an astounding example of what large-format Polaroid film could do.” From here on in, artists were far more keen to dig into the camera’s quirks. Most famously in the 1970s, Andy Warhol used “one of the junkiest Polaroids ever made, a snout-shaped plastic thing called a Big Shot,” writes Bonanos. “It did not have a focus adjustment: it could only take a photo at a distance of about four feet.” Around the same time, Robert Mapplethorpe explored the dual tenderness and toughness of the body with a greater freedom with his SX-70, producing an oeuvre of work that was deemed significant enough to warrant its own retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2008. Then there is the Talking Heads frontman David Byrne who used his SX-70 to take hundreds of close-up Polaroids of the band to make a photomosaic for their 1978 record More Songs About Buildings And Food.

“I liked the way the distortions and mistakes were inherent in the process,” Byrne said in a later interview. Like its print sibling, the typewriter – another talisman I wrote about for this website – the foibles become a part of the yield. Roland Barthes called the act of Polaroid-taking “amusant, mais decevant,” which brings in another important theme when it comes to instant photography: patience. “Why should the imperfections stress you out?” I was asked only a few days before I flew to New York. For the woman asking me, the Italian photographer Felicita Russo – who started experimenting with light painting on instant film in 2018 and helps run an Italian social network called Polaroiders – it is the imperfections that give Polaroids more meaning. This is something I reminded myself of on the days my malfunctioning camera dictated the terms, whether it was the broken clutch strap or the temperamental flash. In lieu of the latter, and in keeping with my Polaroid’s quirks, I focused my attention on the smaller things I may have otherwise ignored. The dapples of light on the Brooklyn tarmac, for instance. Or the speeding reflection of a freeway in a rearview mirror. It became a kind of note-taking that appealed to me as a journalist on the road. “And every time that you don’t get what you are expecting, I ask myself how I can use it to tell another story,” Russo told me of her own Polaroids on the day of our video call. These Polaroids are eventually posted onto her Instagram feed – which is where I discovered them. A new kind of symbiosis. Her multiple suns, for instance, inspired by solarigraphy: the art of long exposure photography that captures diamonds of light moving across the sky.

Instagram, the great deceiver, with its forged white borders, is a nostalgic imitation of the physicality we have lost. We now live in an age of constant and instantaneous image-making. Yet, what is missing? The latest Fujifilm statistics would suggest something that can be profited from. I’m not the only one who has picked up her instant camera in a bid to address questions of transience. Towards the end of last year, the Japanese conglomerate projected a 2024 sales growth in its Instax instant camera business to 150 billion yen, around £786 million, a figure they said they would achieve by building on its Gen Z fan base. How exactly does this contrast with Instagram’s two billion monthly users at a time when our instant digital photographs are struggling to be seen in a sea of reels and ads? Berger saw this many years ago when he said that photography had gone from “ritual” to “reflex”. And with Berger in mind, I wonder whether this romantic revival of analogue technology – Polaroids, vinyl, VHS – is really about returning to ritual again. It’s a quest that is being led by a generation who were born in the very era when my Polaroid was being made. Only a few months ago, Polaroid – whose wild and chequered revival after bankruptcy in the early-noughties is worthy of a separate essay in and of itself – announced a global brand campaign entitled ‘Capture Real Life’, as if to photograph the world on its Generation 2 Polaroid Now and Polaroid Now+ cameras was to reject the illusory one we now scroll through on our screens.

I’m more a subscriber to the American photographer Diane Arbus’ theory that a photograph is a secret about a secret. “The more it tells you,” she mused, “the less you know.” It’s an idea that feeds into my desire to pick up my Polaroid again after all these years, not because I believe that it might bring me closer to a life that feels more real to me but because I’m missing what the Irish essayist Brian Dillon pinpointed as an “affinity” with the pictures themselves. As Dillon himself described them, “Images that stage in their content or form some act of blurring and becoming.” This is exactly how these Polaroids speak to me. “We live in an ocean of images,” Russo replied in partial-answer to my query about the medium’s renaissance; “We’ve seen everything. The only option we have left is to see the same thing differently.” In an age when you can access any landscape on the internet: “What are you going to add?” For me, at least, my Polaroid project this summer was really about memory and time, tangibility and loss. The act of reaching for something that you know, even in that moment of capturing it, is already out of your grasp. Like our memories, too, because what we choose to frame tells us so much about the things that we hold onto – as well as the things that we let go. Ultimately, isn’t that the thrill of an instant photograph? Moments lived, as Berger put it. Not in the photos themselves, but in the stories that lead to them. Like Wim Wenders’. And mine, too. These pictures that never truly show us what we’ve seen.

The Polaroid Photographs

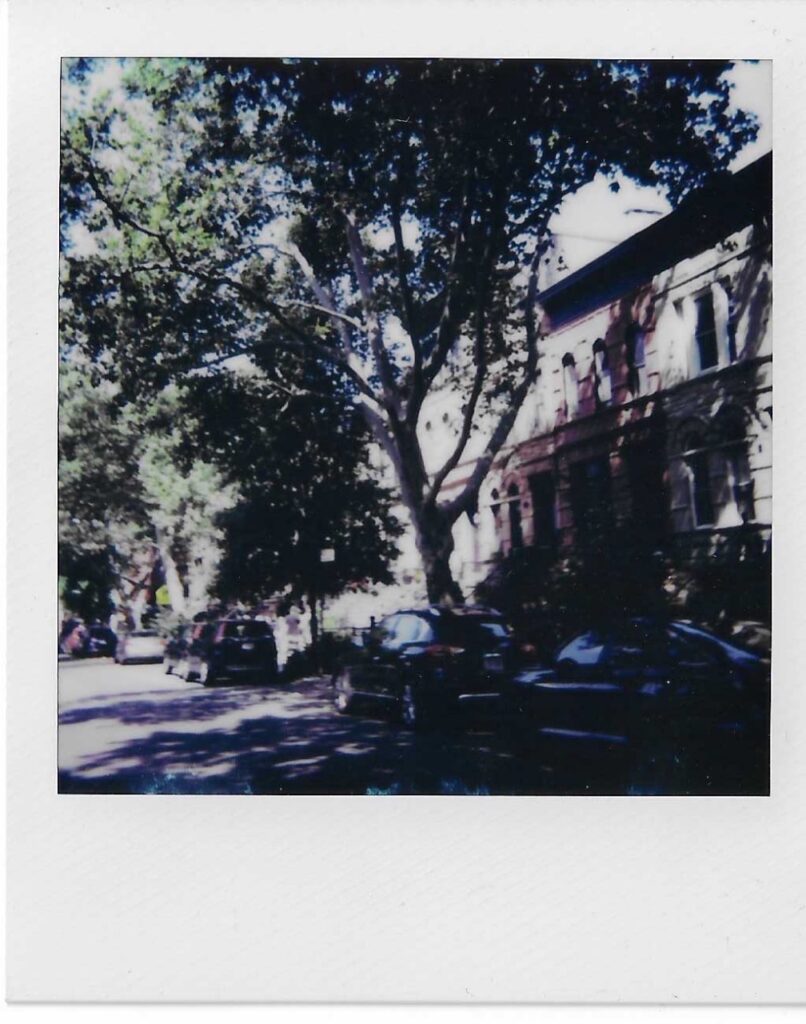

Photograph No. 1: On Miles’s Stoop, Brooklyn (see above)

This wasn’t the image I was intending to capture. A few days before we left for New York, I realised my flash wasn’t working. Multiple Google searches and I’m still none-the-wiser as to the cause but I suspect that it had something to do with the film itself: a Polaroid camera doesn’t have its own source of power, it comes from the film itself. Without the flash, pictures were blurry and out of focus, so I decided to go with that quirk and photograph the dappling light from the trees.

Photograph No. 2: The Not-So-Happy Chef, New Jersey

We found this fella at the entrance to Clinton Station Diner: a roadside eatery that operates from a disused train car from the 1920s. I threw caution to the wind and took his portrait in spite of the flash issues, but I like the effect, like a hashbrown fever dream.

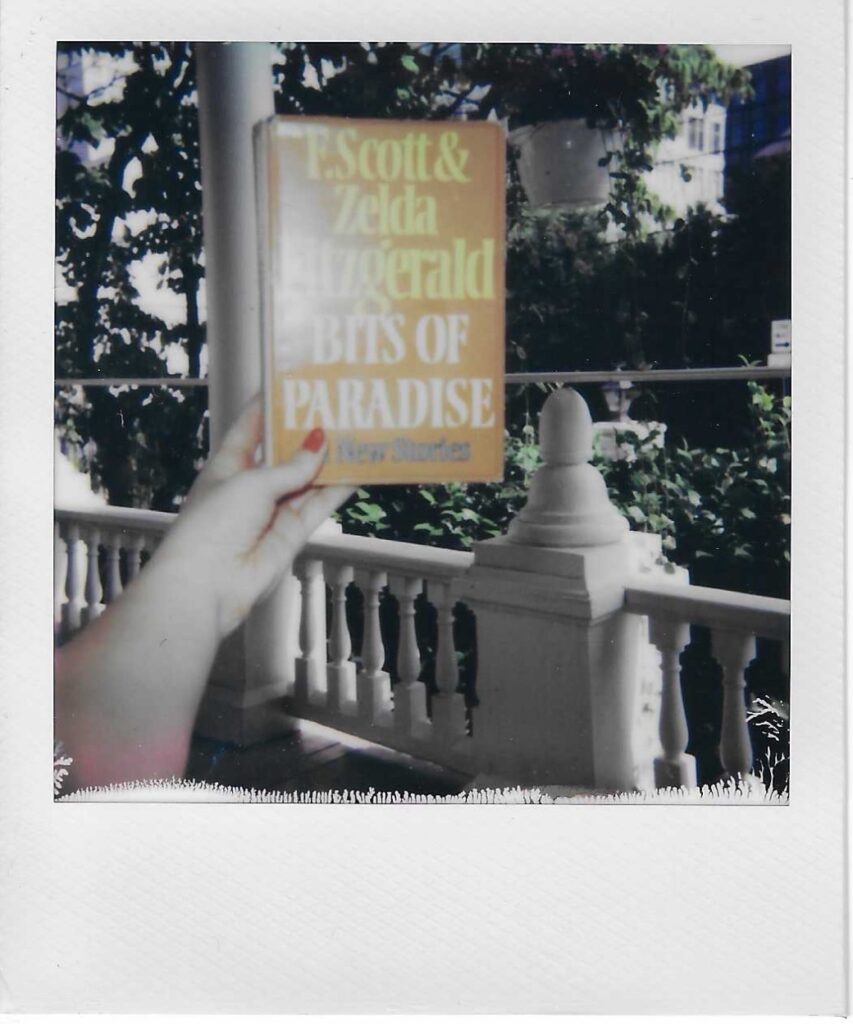

Photograph No. 3: Bits Of Paradise, Charlottesville

I found this book on the library shelf of the B&B we were staying in Charlottesville, Virginia, and took it onto the porch with me where I read some Zelda Fitzgerald stories. That morning, I loaded a new film, and the flash seemed to be charging – at least it was making a noise – so I gave it a go. Too much flash! Let’s call this my Goldilocks moment. The colours are over-exposed, and if you look at the bottom you can see a white pattern, almost like a winter frosting, where I pulled too hard on the Polaroid as it was doing its thing. This Polaroid is indelibly marked by my impatience.

Photograph No. 4: Wocka Wocka!, Charlottesville

An image that combines two of my greatest loves: Muppets and old cinemas. This Paramount opened in 1931 and looked particularly thrilling at night with all its illuminations but my camera wouldn’t have handled all that light. When life hands you lemons etc., photograph during the daytime.

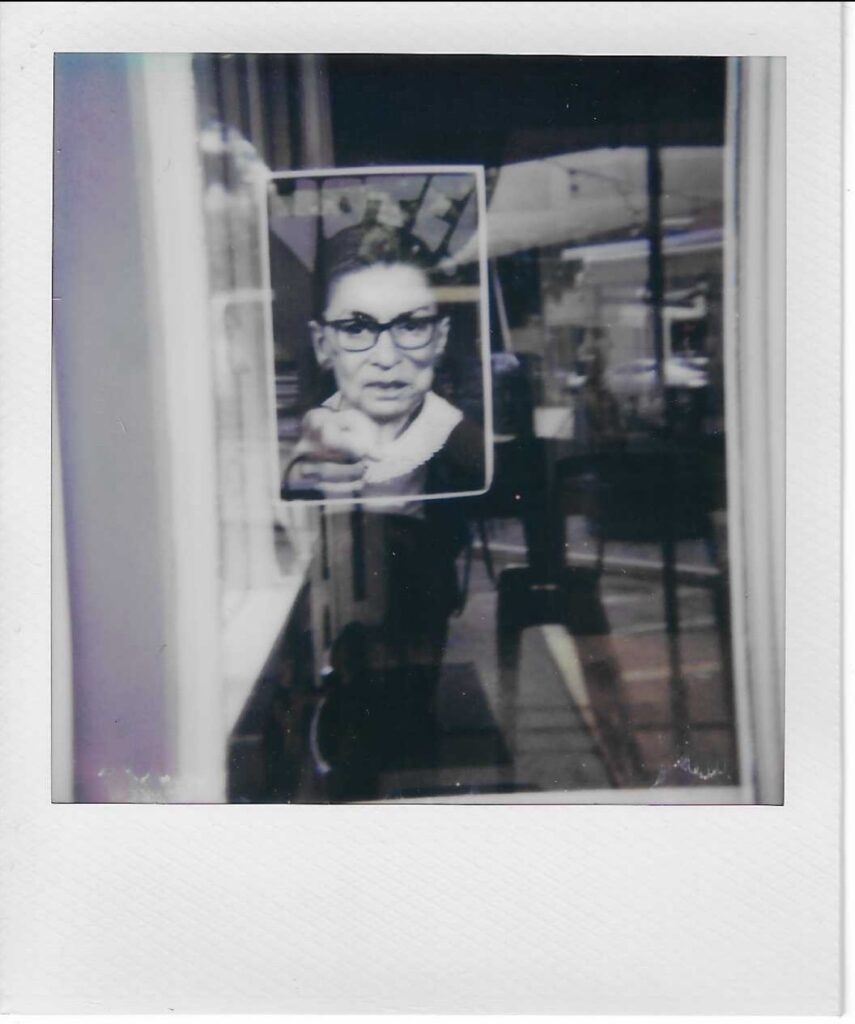

Photograph No. 5: Ruth Bader Ginsburg Says VOTE, North Carolina

We saw a lot of Trump placards on the road from Virginia to North Carolina but my boyfriend urged me not to give him any more air time so I went with this RBG poster, instead, which I spotted on our walk for burritos in Chapel Hill. I wasn’t sure if my camera would handle both the poster and the window that it was bluetacked to, and I’m still not sure that it did tbh, but there’s something about the glassy effect that appeals to me. Only a few days earlier, Biden had stepped aside from the Presidential race and I wanted to document it here. Shadows and light.

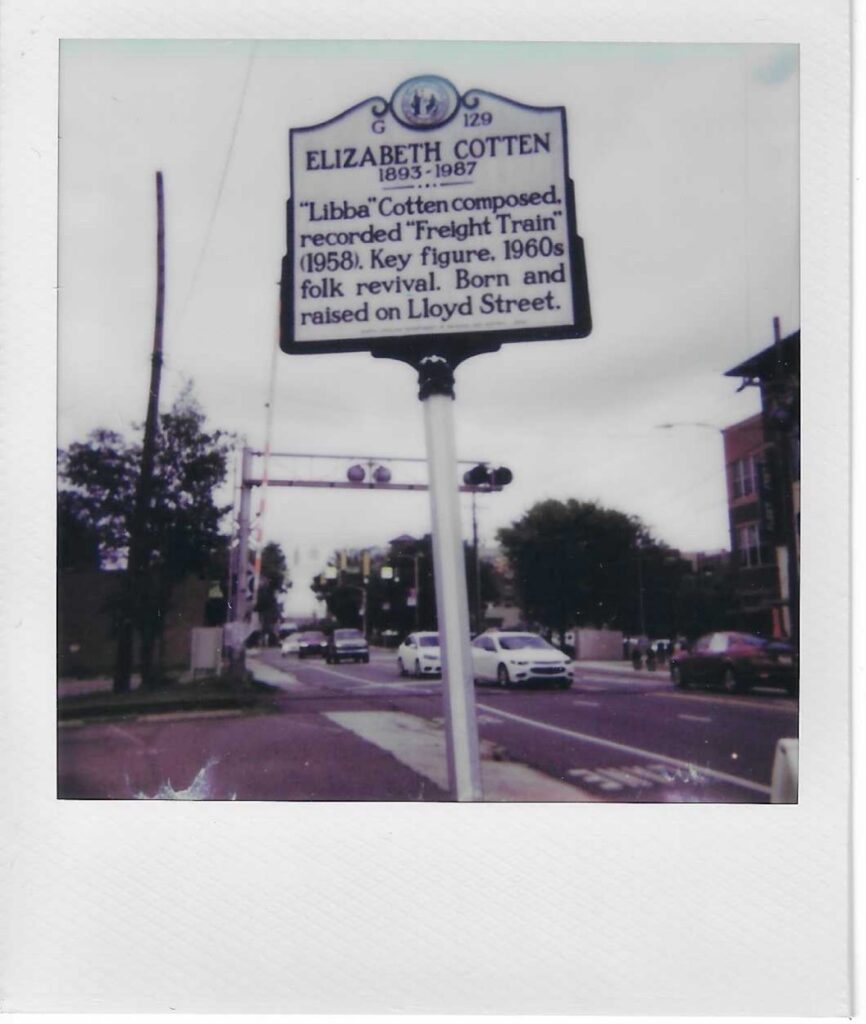

Photograph No. 6: Freight Train On Lloyd Street, North Carolina

It was a stupidly hot day in Chapel Hill and I wasn’t sure how my Polaroid would fare (when I interviewed Felicita Russo she told me that Polaroids are sensitive to temperature: “There is a greenish hue during the winter when it’s cold, and a pinkish hue during the summer when it’s hotter”.) But I think that this came out rather well. I read that Cotten played her guitar upside down and I think this reflects the free spirited nature of the Polaroid, too.

Photograph No. 7: Objects In The Mirror Are Closer Than They Appear, Virginia

I find it interesting that on the day we visited Shenandoah National Park I left my Polaroid behind – as if the majesty of Virginia’s blue ridge mountains would be lost in that square space somehow. Throughout the trip, I focused my camera on the smaller things, leaning in to the randomness of it all; and by “all”, I mean both America and the Polaroid. With this in mind, I wondered what would happen if I took a photo of our cruising car from the rear view mirror. I think that, had I taken it with the close target lens it might have come out a little crisper. But in the spirit of Jamie Livingston: no do-overs!

Photograph No. 8: In Johnny’s Garden, Manassas (see above)

If you know, you know.

Photograph No. 9: On the Delaware River, Philadelphia

A grey morning, and a hangover of epic proportions. The Clientele had played Johnny Brenda’s the night before in Philly and we were taking a short walk by the river before making our way back to New York for their sound check later that day. I like the alabaster quality the image has. And I wasn’t sure the flag would come out, it was a windy morning, but it did, and I was delighted. Here’s to small wins.

Photograph No. 10: Song To Woody, New York

The summer felt more oppressive in New York and when I look at this Polaroid I still feel those stifling temperatures. I took this while The Clientele were soundchecking at Le Poisson Rouge, around the corner from what is left of Cafe Wha?, which isn’t a lot, but old habits die hard.

Photograph No. 11: Send A Salami To Your Boy In The Army, New York

Because a trip to New York isn’t complete without a visit to Katz’s Deli. The second I pressed down on the button a pedestrian entered stage left. That floating head still bothers me greatly.

Photograph No. 12: Bagels On Brooklyn Bridge

I thought that our bag of bagels saved us on this journey to the airport (beset by traffic as we sped through the streets of Brooklyn) but maybe the bridge did, too, taken from the front seat as Manhattan sped alongside us. It goes without saying that I love bridges. A fitting farewell.

Photograph No. 13: James’s Guitar at JFK

I had one Polaroid left in my camera, and James’s guitar had been through a few scrapes on the road, so I thought I’d take its noble portrait before the fragile baggage team prised it away from him for the journey home. Another fitting farewell.