"Since the high renaissance, society has always found a place to go to dream." I’m speaking via Skype to Rhys Chatham, composer for 400 electric guitars and former curator to New York’s legendary venue, The Kitchen. "Whether that was in Bohemia or one area or another area. For art to work," he says, "you need either patrons or government grants, you need press, and you need cheap rents."

For Chatham and his contemporaries, those cheap rents could be found Downtown, in the southern end of Manhattan. A few decades later, when William Basinski was looking for a space to work, no struggling artist could afford to live in Manhattan, so he went to Brooklyn and opened his Arcadia in a former ironworks. It was "a beautiful, magical place," Basinski recalled wistfully in an interview last year for Tinymixtapes. Even the very name Arcadia evokes a utopian promise, an unspoilt idyll.

In the years in between, the location may have changed, forever on the run from the property developers, but the sense of wonder stayed the same. Chatham left New York in 1988 for Paris, at around the time that Basinski opened Arcadia. Returning to the city in the 1990s with his twenty year-old daughter, he was embarrassed to find many of his old haunts had become "sushi shops and bars that charge $10 a beer". But when one of the members of his band took him to a gig in Williamsburg, he started to recognise the expressions on people’s faces, the styles, the ambiance. He went to concerts in a warehouse in Bushwick and thought, "this is like The Kitchen was when we first did it … The kids have found a way."

In the latter half of the twentieth century a whole network of such spaces, dream houses and miniature cockaynes, sprung up in New York in an ever-shifting terrain of creative islets and smugglers’ coves; pockets of creativity that burst through the surface as a result of seismic activity. The period witnessed an unusual ferment of artistic energy that changed fundamentally the relations between the different arts and between the different genres of music. Downtown is a myth, a fairytale; it is a mode of activity and way of thinking more than any strictly demarcated locale, a zone that has constantly mutated ever since this peculiarly American word first entered the dictionary at the end of the nineteenth century.

Like all fairy tales, it began when a small group of intrepid explorers went down into the woods, into the darkest corner of the forest. Rhys Chatham explains, "Artists like Yoko Ono, Walter De Maria, Jackson Mac Low, Robert Morris, La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, Henry Flynt, went down to this area that you weren’t even allowed to live in, called SoHo…"

South of Houston and north of Canal Street in the lowest tip of Manhattan Island, SoHo was once the most populous ward in the city. But as Broadway became what a 1973 New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission report called "a boulevard of marble, cast-iron and brownstone commercial palazzos … the entertainment center of the city," the area was transformed – and fast. The cobbled streets behind Broadway became notorious for their ‘houses of assignation’, the middle classes left in their droves, and manufacturing took their place. The 1860s saw a 25% drop in the population as factories and warehouses moved into the ward.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the city centre had moved north and the more upscale businesses with it, leaving just paper waste and textile firms behind. The district slumped and for several decades saw little change. "It was not until the 1960s that a new movement began to stir," continues the Landmarks Preservation Commission report. "This, surprisingly enough, was caused by the trend among artists to paint on larger and larger canvasses…"

"Richard Serra would move down there and say, this is a great place to do my sculpture," Chatham continues, "Dancers need space. You’d have Yvonne Rainer in a big loft. I got my first loft in SoHo in 1970. I was eighteen and couldn’t wait to move out of mum and dad’s house. I had a loft of 1,200 square feet for $180 a month. No-one wanted to live there. No-one would even think of living there. First of all it was illegal…"

In 1960, when Yoko Ono started presenting events in her loft at 112 Chambers Street in TriBeCa (that is, the triangle below Canal St.), her friends from the Juilliard School of Music, where her husband Toshi Ichiyanagi studied composition, thought she was crazy. "My friends in classical music advised me not to do it downtown," she told Kyle Gann in an interview for the Village Voice; they told her, "you’re wasting your money, nobody’s going to go there. Anybody who’s interested in ‘serious’ music goes to midtown."

Ono’s first series of loft concerts was curated by a composer named La Monte Young, a former academic dodecaphonist who had encountered the ideas of John Cage at the famous Darmstadt summer school in 1959. Young put together a series with Richard Maxfield, a former student of Cage’s at the New School for Social Research who was interested in experimenting with magnetic tape.

Ono performed a piece called Wall Piece for Orchestra which required the instrumentalists to bang their heads against the wall, while Henry Flynt improvised on homemade instruments made of toothpicks and elastic bands. La Monte Young released a butterfly into the audience and called it Composition 1960 #5, wrote a piece which invited the performer to feed a bale of hay to the piano "or leave it to eat by itself", and drew two notes on a stave, seven semitones apart, with the indication "to be held for a long time". Marcel Duchamp was in the audience, smiling appreciatively.

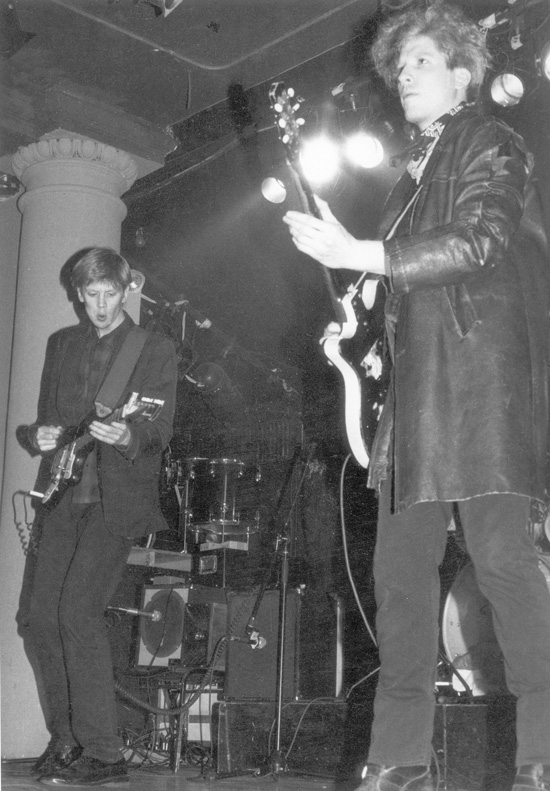

feature continues below image

The floodgates were open. George Maciunas, ringmaster to the international Fluxus circus, helped many artists to purchase former industrial buildings, many of them ex-sweatshops, and convert them into combination living and working spaces. They called them ‘fluxhouses’ and though they lacked trivial things like heat and plumbing, their vast open spaces made ideal performance spaces. La Monte Young and his wife Marian Zazeela moved to a loft on Church Street in August of 1963 and began to dream of a concert space where the music would never end. It would be a complete light and sound environment, and it would be called the Dream House.

Meanwhile, Steve Reich and Philip Glass’s ensembles were playing regularly in lofts owned (and lived in) by the likes of Meredith Monk and Yvonne Rainer. Ornette Coleman opened up his Artists House on Prince Street in the West Village in 1968. And Phill Niblock renamed his own loft Experimental Intermedia as a venue for his films and microtonal compositions, and increasingly those of many other artists and film-makers too. It was at Niblock’s place that Rhys Chatham saw his first loft concert. "The difference when you heard a concert at Phill’s," he says, "is that it was his living room, so we’d all be lounging around on couches and beds, sitting on the floor or whatever, and it was a very, very comfortable, very relaxed environment. It was something informal. I suppose we could call it the modern day chamber music."

At that time, in 1970, Chatham was nineteen years old and had been studying electronic music with Morton Subotnick at New York University, where he had access to one of the first generation Buchla 100 Series electronic synthesisers. At Subotnick’s studio at NYU, Chatham had created some music for a number of art works by an older couple named Woody and Steina Vasulka. "I gave them lessons on the Buchla 100 series and they were so touched, and I guess they thought I was so cute," he says.

On June 15th 1971, the Vasulkas opened up a space in the Mercer Arts Center, a huge former hotel in SoHo that had been divvied up into a series of studios. The Mercer Arts Center was home to a rehearsal space for theatrical directors like Richard Foreman, but it also contained the Oscar Wilde Room, which was occupied by the New York Dolls for much of 1973. The Vasulkas’ space was originally intended to be a venue for the newly emerging genre of video art, but they decided to have a contemporary music night every monday and asked Chatham to curate the series.

The story goes that the space had once housed the kitchen of the hotel, but Chatham doubts this story, "because the space was too large to be a kitchen. It was this humungous loft with ceilings that were probably thirty feet high. Woody and Steina had a loft near Union Square and they’re very sociable people and so many ideas were hatched in their kitchen. That’s where they got the idea to call it the Kitchen."

From the beginning, Chatham’s idea was that the Kitchen’s music programme could be a kind of über-loft. "People like Philip [Glass] were doing these concerts in people’s living rooms, and we thought we could do it better. We had a beautiful sound system and a beautiful Steinway grand and we did publicity. So it was another place to play where everything was in place, so it would cost the artists less to put their own concerts on."

One of the first people Chatham invited to play was La Monte Young. "I had studied his Selected Writings the way only a teenager can. So I called up La Monte, completely innocently. Even back then, he was really a superstar on the downtown scene, but I called him anyway." Young invited Chatham over to his place on Church Street and played piano for him on an upright tuned in just intonation. Mindful of the site-specific nature of much of his music, however, and the long periods of tuning and preparation he required in situ before a concert, Young was somewhat loath to perform at The Kitchen. "Then Marian said, well, you know La Monte, we don’t have any grocery money for this week, so maybe we could play the record and sell them. So that’s what we did. It’s the only concert we did like that at The Kitchen. Afterwards, Marian was quite pleased, she said, well, we got our grocery money."

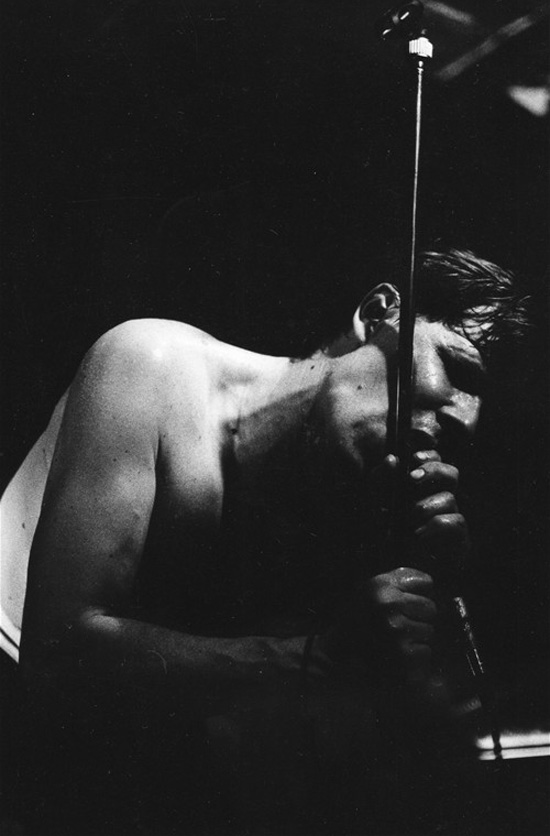

feature continues below image

While The Kitchen’s programme of post-Cagean composition went from strength to strength, other loft scenes were brewing in the same neighbourhoods, other scenes and other islands of activity with scant communication between them. After Ornette Coleman’s short-lived Artists House, the loft jazz scene had exploded in the downtown area, nurtured by exclusion from the prestigious Newport Jazz Festival. Woodwind player Sam Rivers had Studio Rivbea on Bond Street, commemorated on the legendary Wildflowers compilations released by Douglas Records in 1977. Down the street, singer Joe Lee Wilson had The Ladies Fort, while in the East 20s, there was the Jazzmania Society.

At the same time, even in the same neighbourhood, DJ David Mancuso started to use his own loft as a venue for a weekly series of all-night acid-fried dance parties. Dancers brought whistles and rattles, making the whole space into one big percussion section, and Mancuso would mix and stretch the funkiest bits from a wide range of music, from Philly soul to African percussion records. Ever mindful of cues from the crowd, he would shape his selection of tunes into a sonic journey, a narrative of multiple climaxes. "What had emerged," writes Tim Lawrence in his book Love Saves The Day, named after a note on Mancuso’s flyers, "was a social and egalitarian model of making music in which the DJ played in relation to the crowd, leading and following in roughly equal measure."

"Clubs are set up for the purpose of making money," Mancuso told Lawrence in a 2007 interview. "This is not what the Loft is about. The Loft is about putting on a party and making friends … For me the Loft is all about social progress." A similar sentiment would be put forward by Rhys Chatham in relation to his time at The Kitchen. "None of us were getting paid. For the artists we charged at the door and none of this bollocks of 50% of the door," he tells me, "we gave [the artists] 100% of the door."

But despite their similar ethos and physical proximity (by the mid-70s the Kitchen was on Wooster Street and Mancuso’s Loft was just around the corner on Prince Street), the Loft and Kitchen remained two different worlds. And might have remained so, if it wasn’t for a series of changes in the world of contemporary music at the end of the 1970s.

In the mid-1970s, the post of music director of The Kitchen was taken over, first by Arthur Russell and then the trombonist Garrett List. Between them, Russell and List started breaking down some of the venue’s unspoken taboos.

A classically trained cellist from Oskaloosa, Iowa, Russell had moved to New York in 1973 to study music. After an argument with Charles Wuorinen, he promptly dropped out of college and became music director at The Kitchen. Initially, he hewed close to the established traditions of the venue but there was this little local band he liked, in whom he detected some of the spirit of musical minimalism enthused with the energy of punk and new wave. So he took a chance and booked them. The name of that band was The Talking Heads. "It caused quite a lot of comment at the time," Chatham remembers. "Nobody had any idea what CBGB’s was. We thought of this as an anomaly."

Russell’s tenure as music director was short-lived, and he was succeeded by the trombonist Garrett List, who had played alongside Rhys Chatham in La Monte Young’s Theatre of Eternal Music. Towards the end of the decade, List had started playing with Frederic Rzewski, who at that time was busy hipping New York’s contemporary music scene to the virtues of free improvisation and the exciting things going on in the loft jazz scene. So List started inviting the likes of Art Ensemble Of Chicago and Don Cherry to come down. Meanwhile, Arthur Russell had been taken by a boyfriend to a place called the Gallery, where the DJ Nicky Siano was building on the new sound developed by Mancuso at the Loft. Pretty soon, he was there every week.

"Back in the 1970s," Chatham explains, "there was this pyramidal hierarchy where you had music of a classical tradition on top, jazz somewhere below, and rock was barely considered music. What we were trying to do back then was to break down these barriers … This music was intermingling and merging together and finding common points of reference." Increasingly, the programme at The Kitchen began to reflect this.

Into this increasingly liberal music environment stepped Michael Gira. Born in Los Angeles, Gira had studied at Otis College of Art where he had met and befriended fellow student Kim Gordon. In 1979, he moved to New York, attracted by the "apocalyptic environment" suggested by the film Taxi Driver and the no wave scene them emerging from downtown art galleries. "It seemed very appealing to me, somehow, that New York," he tells me over the phone.

"However, when I got to New York, no wave was already dying. There was this void for a short period of time musically around New York, I think. It was just this kind of fake jazz music that was going on. British dance music was kind of infiltrating the clubs." Gira’s band Swans and Gordon’s band Sonic Youth started playing around town together, hoping, as he tells me, to fill "that void with something else. We created our own space and we were closely aligned for a short period of time."

Gira recalls Swans being booked by Chatham to play at The Kitchen during the latter’s second tenure as music director, taking over from Garrett List again at the end of the decade. "I recall that when we played there the police came and shut it down because we were so loud."

But there were other spaces, a little further off the radar. "There was something called the Sin Club that was on Avenue C and Second Street or something, which was at the time just total apocalypse. Gunfire all over the place, burnt out cars everywhere. I remember that the PA there got heisted by the local police." Inside the Sin Club "was just a graffitied dry wall space. There were no amenities really. Some sort of laughable PA." Similar sorts of spaces would regularly "pop up and happen for a year or six months."

Gira had a rehearsal space that Swans shared with Sonic Youth. "I found a storefront on 6th St. and Avenue B for a hundred dollars a month," he explains. "It was just a shell and I had to build to make it liveable. I cut it in half and lived in one half and we had a rehearsal space in the other half." Working as a construction worker at the time, Gira set about making his new home into "an impenetrable fortress". The place had no windows except a little porthole in the back and he fitted the doors with double bolt locks. "It was a pretty dangerous neighbourhood," he says. "I heard gunfire every night. I would hear machine gunfire."

Within a few years, however, Gira was keen to get out of New York. "I just got sick of it. For me, it was just a never ending struggle." Chatham left permanently for France around the same time. "The rents got more and more expensive," he recalls, "so those of us living in SoHo moved to TriBeCa. Then that got more expensive, so we moved to the East Village. Then I moved to France…"

feature continues below image

William Basinski moved to New York only a year after Michael Gira. "We were a few years too late for the dirt cheap huge lofts in Soho and Tribeca," he explains. "There were still some shit holes available but we’d talk to tenants and they would tell us, ‘our landlord is crazy. He’s trying to kick us all out. He chopped the power lines with an axe and threatens us.’ Well, we were determined, damn it. Somehow we got to Brooklyn, I can’t remember how."

With the visual artist James Elaine, Basinski moved into a "5000 sq. ft. former sweat shop on the 6th floor of a beautiful old seven storey brick building with 26 rotten windows." Bewitched by the murals on every subway train and horrifed by the stench of urine and the "huge rats having the time of their lives, they imagined their new home as the "edge of the earth", like something out of Antonioni’s Il deserto rosso. They went to The Kitchen and to Experimental Intermedia and visited La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House.

Basinski spent a few years playing in different bands, while Elaine struggled to get collectors to cross the river to see his work. Finally, just as they had finally come to some sort of permanent settlement with their landlord, they got a letter in the mail saying the city was condemning the entire neighbourhood and they had to move out.

With a buy-out from the council – thanks to a law firm who took their case on pro bono – they went on the hunt for somewhere new. The first one was a commercial property in Williamsburg. "We got there not knowing where the hell we were," Basinski recalls. "The door was open and we walked up into this amazing gothic ruin full of pigeons, vaulted ceilings in repeating octagons, peeling paint, pigeon shit, filth, decay, floor to ceiling windows with views of Manhattan and the East River – it was gorgeous!" They took it. Basinski’s friend Chauncey suggested they call it Arcadia, after the mythical home of the god Pan. "I knew we had to have a stage at the end, and a performance space. We had to share this. It was too beautiful not to."

"We got the place in spring, worked our asses off and had it shining by late June with the help of all of our artist and musician friends, still no gas for the kitchen and heat until November, but the first concert was 4th of July 1989." Pretty soon they had a regular concert series and an inhouse recording studio. "We nurtured people we liked, and everyone from various bands helped each other, so there was a kind of core group for a while. I was developing an agenda and a curatorial focus. Arcadia was a testing ground for bands I wanted to produce."

Though there were still a great deal of artist-run spaces and loft gigs at that time – particularly in their neighbourhood in Williamsburg – Basinski insists "there wasn’t really anything comparable to Arcadia as far as baroque beauty and glamor [went]. It was unique. We thought it would last forever, but no." Eventually the lease ran out and it was going to be ten grand a month to renew. "That was the end."

Basinski and his "repertory company" lasted nearly twenty years in their "Venetian palazzo" on the East River. "No-one ever forgot a visit to Arcadia," he tells me, not without a melancholy tinge for times gone by. But he seems genuinely stoked about the concert series he has coming up in "sparkling London".

In the meantime, the tectonic plates of New York’s effervescent cultural scene continue to shift and stir. "There’s a place in Bushwick a bit further out called the Secret Robot Room," Rhys Chatham tells me at the end of our conversation, "these artists leased a building so you’ve got visual artists there, they do concerts there, Oneida rehearses there.

"SoHo lives on in Bushwick," he says. "The scene is vibrant there."

William Basinski’s Arcadia Series takes place at venues around London over the coming year, in association with Art Assembly.

Tomorrow, Wednesday 12th March, Michael Gira plays solo at St. John’s Church in Hackney, alongside Basinski. On Thursday 20th March, Rhys Chatham and Charlemagne Palestine play a collaborative show at St. John’s Church, again with Basinski. Click here for more information about the full series confirmed so far, and to buy tickets.