“Tiny details imperceptible to us decide everything!” suggests one of W.G. Sebald’s characters in his novel, Vertigo (1990). It seems as apt a statement as any to introduce his work. In a brief but successful literary career, the German-born, East Anglia-based writer quickly rose to prominence, influencing an array of writers and artists. With what would have been his 75th birthday on the 18th of May this year, two exhibitions in Norwich – Lines of Sight: W.G. Sebald’s East Anglia at Norwich Castle and W.G. Sebald: Far Away – But From Where? at The Sainsbury Centre – shine a light on his complex and deeply layered work. Yet what do these exhibitions say about Sebald as a writer, not simply in terms of the very process of writing that marked his four main novels, but in regards to the resonances of his themes today?

Winfried Georg Maximilian Sebald, or “Max” to his friends, was born in the Bavarian Alps in 1944. He studied English and German literature in Germany and Switzerland. In the mid 1960s, he travelled to England where he first taught at the University of Manchester. Aside from a handful of brief stints abroad, he settled in Norfolk, working his way up the academic ladder at the University of East Anglia. He became a Professor and the chair of European Literature, as well as founding the pivotal British Centre for Literary Translation. There’s a reason why their yearly lecture is named in his honour.

Though publishing late in life, Sebald’s writing career was unprecedented in its rise. His first novel, Vertigo, was published in German in 1990 though wasn’t translated into English until almost a decade later. It was followed in German by The Emigrants (1992) and The Rings of Saturn (1995) whose eventual English translations, in 1996 and 1998 respectively, garnered critical appreciation. The Rings of Saturn won the L.A. Times Book Prize and Sebald found himself revered, seemingly much to his own horror, during his own lifetime. In spite of publications of previous essays and poetry collections since, Sebald’s literary life was arguably bookended by Austerlitz (2001), his first book to be published initially English before the German translation, and with a sizeable book deal this time around.

In this time, Sebald’s rise in the literary pantheon had been unparalleled and so his early death, from an aneurism whilst driving in Norfolk on the 14th of December 2001, cut short a career that clearly had a great deal still to give. Even Horace Engdah, the previous secretary of the Swedish Academy put his name forward as a potential candidate for the Nobel Prize had he lived; a startling placement for a writer of only four novels. There is no doubt then as to the power of Sebald’s work which is a stark mixture of meandering travelogue, archaeologies of history and dissections of melancholy, as well as rich and detailed character portraits matched only in atmosphere by the grainy photographs and seemingly inconsequential ephemera that litter his works.

Yet it is this backlog of information that sometimes makes discussing Sebald’s work difficult. Not only has a veritable cottage industry quickly assembled in discussing and analysing his several books, especially in academia, but there’s an aura to his writing which is easy to become possessed by. It is with this admission in mind that I found the two exhibitions to earnestly show a more tangible, practical way to understanding the man and his work. For me, it highlights two key aspects to it: the ability to detect the darker elements of our shared pasts constantly threatening to repeat, and why his engagement with walking and place was dramatically different to the images typically, and often unfairly, associated with such perambulatory forms of writing.

Wandering After Death

The Rings of Saturn (W.G. Sebald as ‘the narrator’). 1995. © The W.G. Sebald Estate

Walking around Norwich Castle’s exhibition is very much like following a condensed version of The Rings of Saturn. It is arguably the writer’s most revered book, built on a long walk around the East Anglian coastline, long enough in fact to have hospitalised the writer soon after completing it. Along with the photographs from the book (and, most intriguingly, those that didn’t make the cut), various objects either mentioned or actually shown in its various pages have been sourced to appear within the four walls of the exhibition. This sense of meandering, especially in The Rings of Saturn, has often had Sebald wrongly associated with other lone walker writers, flâneurs and new psychogeographers; as if he was merely another voice following in a much practiced and oversaturated field, at least here in Britain. This exhibition allows for a deeper engagement with his work.

Sebald was often blasé about the photographs he took whilst on his walks and, looking at the results on display, it’s clear that he was doing himself a typically self-depreciating injustice. The East Anglian light is stunning, the shades and tones rich, the landscapes detailed and the eye perceiving them curious. Such images were famously photocopied down to achieve the black & white Xerox graininess they’re rendered with in his books. The reality of the images and their qualities is intriguing but, more importantly, there’s a dark romanticism behind them. Unlike other such journeyed narratives around Britain’s landscapes and cities, there’s little desire to add layers of either grubby authenticity or gushing pastoralism, both seemingly so essential to other books of this form; as if the admiration of such things was new rather than simply another collection of fetishes. Sebald instead plays upon the banal – for a deeply underrated strain of black humour – and the vastness of his places. The melancholy is an effective editing process, if anything removing the clichés.

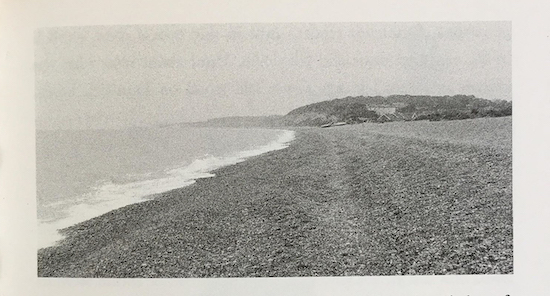

The landscape as seen in The Rings of Saturn

Sebald’s original photograph

For me, this means Sebald has more in common with the writers whom he openly admired such as Robert Walser, Adalbert Stifter or Thomas Bernhard; writers he himself often wrote about and arguably kick-started a wider appreciation of in the English language. The Rings of Saturn, for example, has far more in common with the meandering microfictions of Walser than any British walking books, fiction or nonfiction. The book also has more in common with Stifter’s The Bachelors (1852) – with its detailed landscapes seen with a mixture of darkness and practicality – than any novel wandering the endlessly trekked Lea Valley or the like. His eye builds contrasts with the reality of what plagued the picturesque. The stark renderings of place and atmosphere lure the reader in until close enough to see the horror behind the history. This contrast also makes the syntax of his writing compelling and antiquarian, with far more in common with older European essayists than twentieth-century British fiction writers. His flowing sentences are seemingly taken out of time.

W.G. Sebald, Untitled (East Anglian Landscape with Shadow). 1997. © The W.G. Sebald Estate

Of course, not everyone has been satisfied with Sebald’s vision of the East Anglian landscape in particular, even though it was by no means the only place he wrote about in such detail. Both the naturalist and writer, Richard Mabey and Mark Fisher, were critical of Sebald’s representation of Suffolk. Yet both their criticisms, in their differing ways, can be explained and contextualised. There’s firstly the obvious aspect of Sebald’s work still ultimately being fictional. It’s rather like being frustrated at Émile Zola for his representations of Paris or at Raymond Chandler for his portrayals of California. That same stretch of coastline that Sebald found barren and melancholy is a haven for wildlife and a resort for birdwatchers who flock regularly to many sites there. Minsmere in particular stands out as an obvious omission, housed between two of Sebald’s pivotal markers in The Rings of Saturn: Sizewell Nuclear Power Station and the crumbling village of Dunwich. A Mabey-esque wanderer would probably have found several books’ worth of excitement and joy at the wildlife on display in just that spot.

Fisher is slightly different. The landscape was instead a genuine place of solace and personal happiness throughout his life, a refuge from the increasingly stressful academic and digital world. For Fisher, the question was how could a writer not find within the various beautiful vistas and flat, never-ending horizon lines, a sense of comfort; a chance to rebuild the walls constantly knocked down by Post-Capitalist depression. “The landscape functions as a thin conceit…” he wrote critically of Sebald’s portrayal. Fisher did, however, express a potential change in view of the writer’s work in a review of Grant Gee’s documentary, Patience (After Sebald) (2012). His overarching criticisms seem to be more born of reactions to Sebald’s work and the general machinations of the industry to create and portray “great literature” than anything else.

Whether such rehabilitation occurred in Fisher’s eyes is sadly a question that will remain unanswered. Again though, the context of Sebald is worth noting: the eyes from another continent avoiding all forms of nostalgia, the discipline to stick to an aesthetic, partly autobiographical, partly in character with the narrators of his books. All of these aspects explain the differing views of the landscape, as much a fictional character as any other, and also attest to why Sebald is so different from the more typical perambulatory writers, arguably for the better.

The Veil

With some suggesting that Sebald inaccurately sketched places, bending them to suit his needs, it’s unsurprising to find that the most intriguing aspect of the exhibitions, and Sebald’s writing as a whole, is the sense of trickery that lies behind it; its mixture of fact and fiction, its narrator a shadow-self of the writer, its history real and yet its figures often half fictionalised. Of course, such sleight-of-hand manoeuvres are clear when properly dissecting his work, whether through walking around the places his ghostly alter egos wandered, or even researching the writers that inspired him.

Such trickery became most powerfully apparent when discussing the Far Away exhibition with one of its curators. The exhibition was still being installed during my visit to the brutalist campus of the University of East Anglia, and so the conversation tended towards the photographs of Sebald’s rather than the artwork in the show by Tess Jaray and Tacita Dean. As in the other exhibition, Sebald’s photographs were laid in roughly the order of the book they appear, Austerlitz in this case, along with many that didn’t make the final text. There’s a beautiful curiosity within the photos, a moment perceivable where it’s obvious that Sebald discovered the panorama setting on his camera and experimented until the photos fitted into his schemata for the book (something often assumed to be cropped in the formatting of the photos as in his previous work). The journeys here are a far more sporadic display of trips than the more linear Rings of Saturn walk, traversing locations from East London to Paris, Marienbad to Prague, lending the photos a sense of flux.

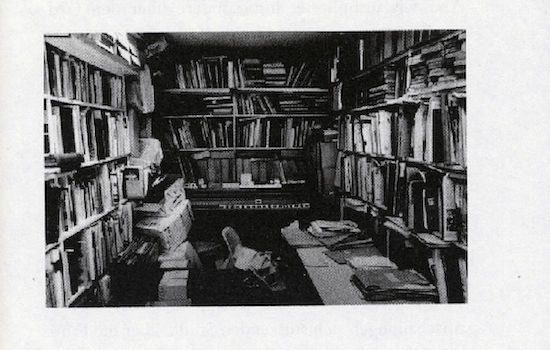

One of the photos in particular caught my eye, of a messy office space supposed to be that of Jacques Austerlitz, the main figure of the novel. I had seen the photograph scanned and published online several times, its archaic fustiness being typical of Sebald’s atmosphere and tone. It had also been falsely attributed as being Sebald’s office several times – as if the dividing line between the narrator and writer was always inescapably paper thin. I was curious then about finding out more. “You’d be surprised to learn,” the curator said, “that it’s actually an office of one of Sebald’s colleagues.” Even more intriguing, however, was the revelation that said office, so antiquarian looking and dusty, was actually directly below where we were standing in the Sainsbury Centre at that point. The office had been one of the metallic cubicles below us, housed in the incredibly futuristic looking hanger, which is now home to an array of mostly modern design work and sculpture.

Sebald describes the office in the following passage in Austerlitz:

“Almost every time I went to London in the years that followed, I visited Austerlitz where he worked in Bloomsbury, not far from the British Museum. I would usually spend an hour or so sitting with him in his crowded study, which was like a stockroom of books and papers with hardly any space left for himself, let alone his students, among the stacks piled high on the floor and the overloaded shelves.”

The deception was clear. Comparing the photograph to the reality of the space, a reality which I would have remained oblivious to had it not been pointed out to me, showed Sebald’s true skill and the fictional disjoint in his work; in casting believable veils over reality in order to do justice to our troubling historical trauma. With this realisation, the veil was no longer shrouded. And yet what was left in its place was equally as powerful and mysterious: namely the question of why, knowing the tricks and mechanisms deployed in his work, Sebald’s novels still retain a powerful essence of moral truth. As with so many things connected with the writer, it is likely to remain a mystery, a cobweb seeming to briefly find shape and design before floating back into the ether. But perhaps Sebald’s troubling sense of accumulated history contains the answer.

The Accumulation of History

Writing this on the day of the European Elections, one particular idea of Sebald’s feels starkly resonant. The deeply moribund character that occupies even his lightest of novels seems to be tracking the root or source of the narrator’s melancholy. Often in his novels, the site or source of this feeling is located unconsciously in history though it becomes more complicated than simply an act of remembrance or haunting. Instead historical calamities seem to emerge out of patterns. The Sebaldian narrator – whether through walking a landscape (something that happened a lot less than is often suggested) or talking to people he meets on his travels – finds such patterns in history and recognises his inescapable place within them. This is evident whether in the past or in the present as it collapses into the future.

This was partly autobiographical, stemming from Sebald’s own fear over his father’s role in World War Two, hence its lingering power, especially The Rings of Saturn which deals with the fears of what could be called the accumulation of history. Essentially, the realisation is one of growing catastrophe. The tragedies of yesteryear, whether the World Wars, their foreshadows in previous colonial conflicts or the formation of early empires, seem to accumulate. The mechanisms behind them gain momentum, rather than slow down. Such historical events from the past weren’t something that could be directly learned from positively either as is so often suggested. Instead they were merely a foreshadow of a greater calamity ahead. As the writer famously put it, “We learn from history as much as a rabbit learns from an experiment that’s performed upon it.”

The effect this has on Sebald’s curatorial eye is there for all to see in his prose, but also in his photographic subjects too. In the Lines of Sight exhibition, his eye roams almost haphazardly to express this quiet trepidation of the future, marked by memories of previous epochs threatening to repeat. He finds synchronicity at the Orford Ness weapons testing facility on the Suffolk coastline, the photos almost post-apocalyptic, to the point where the landscape seems to resemble a place hit by the weapons actually researched there (the site was the testing station for the firing mechanisms of a variety of large scale weaponry, including nuclear warheads). Further along the coast, Sebald ties this apocalypse to a natural one, an ecological mirror in the form of the lost town of Dunwich, once one of England’s largest ports, since mostly fallen under the waves.

Ecological catastrophe is present in these photographs as much as man-made catastrophe, the two seeming to speak the same language on some basic level. But the sense of accumulation is there. It can be felt through something as simple as the image of a Jewish grave in Tower Hamlets Cemetery or an East Anglian cliff top falling into the sea; the bones from the Greyfriars Priory intermingling with the pebbles on the beach, as if all of the stones were somehow gathered there to acknowledge some mass extinction. As the results roll in for the election in the coming days of editing, switching between writing this and watching in banal horror once again, it feels almost absurd to call Sebald’s writing timely. He was merely watching with a wider grasp of such historical momentum, the wheel still sadly turning.

Sebald as a writer saw simultaneously that fiction could be a useful way to address real echoes from the past and, equally, that such a past benefited from certain freedoms allowed for within the novel. Considering his chief subject (albeit almost always addressed indirectly) was The Holocaust, it’s unsurprising to find him creating fictional imprints to whisper greater truths. Staring head on was, and still is, almost unbearable, as the echoes begin to repeat.

For more information on the Lines of Sight exhibition at Norwich Castle go here and Far Away – But From Where? at UEA’s Sainsbury Centre here