This might sound ridiculous, but if you’d walked into a record shop in 1955 on the hunt for new music that was radical and unusual, you might well have been handed a copy of an unknown piece of dazzling, nervy baroque music, The Four Seasons, by a fringe Italian composer called Antonio Vivaldi.

The Four Seasons is now so ubiquitous it’s almost impossible to imagine how strange it would have sounded when it was first heard, and almost no one had heard The Four Seasons before 1955. Or rather, they had, but not for 200 years. In his time, Vivaldi was famous and The Four Seasons, written in the 1720s, was a bona fide cross-Europe smash. But, then as now, careers can collapse quickly and when he died in 1741, broke, so did his music. Incredibly, it only crept back into public consciousness again after the Second World War, with The Four Seasons leading the charge. And although it had been recorded a couple of times before 1955, it took an Italian group called I Musici with their co-founder Felix Ayo on lead violin to turn it into a big-selling album.

So, Vivaldi became a star for the second time in the same year that Bill Haley & His Comets had a hit with ‘Rock Around The Clock’, which broke rock & roll in the mainstream. And that’s just one curiosity of many in Vivaldi’s astonishing story.

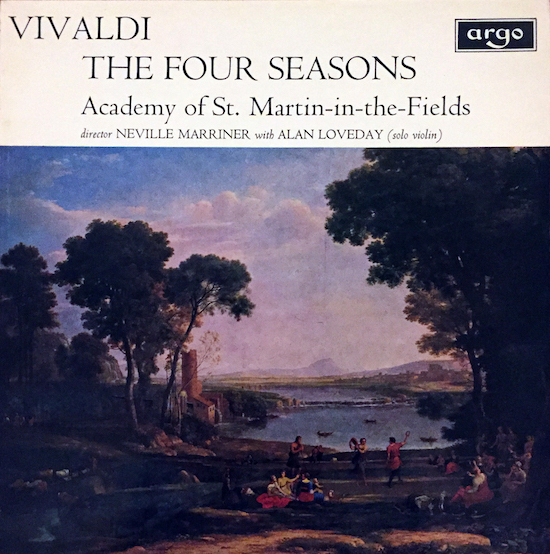

I Musici’s Four Seasons was such a success that they remade it four years later in stereo and sold many millions of copies over the next few years. According to music writer Norman Lebrecht, it’s the third best-selling classical record of all time, but the piece itself “was still an esoteric fad, not yet a tourist staple” until it fell into the hands of Britain’s Neville Marriner and his group, Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. Their brilliant, one-take recording from 1970 captured the zeitgeist and also flew off the shelves. Is it the best version? No idea; there are now more than 1,000 recordings, but to my ears at least it has a crispness of attack that’s exhilarating and it made me realise that The Four Seasons is so much more than shopping-centre muzak.

The Four Seasons doesn’t sound anything like the kind of Germanic baroque music that didn’t get lost to time. It’s fiery, ultra-passionate, very Italian and the pop music of its day. But Vivaldi wasn’t looked down upon. There’s no record of whether Bach specifically heard The Four Seasons, but he knew of Vivaldi, loved his music, and nicked some of his best ideas. He also arranged half a dozen of his concertos for other instruments, and that connection between two giants born seven years apart (Vivaldi in 1678, Bach in 1685) ensured Vivaldi had at least one footnote in music history for the two centuries he was gone.

Vivaldi’s personal story, which we’ll get to, is quite something, and so is the story of how he was re-born. I Musici’s hit record might have helped him cross over to a popular audience again, but research into Vivaldi began earlier in the century, spurred on by two bizarre occurrences. The first concerned a musical hoax perpetrated by the Austrian-born virtuoso violinist Fritz Kreisler, who toured Europe in the 1910s and 1920s playing supposedly unheard works by past masters that he claimed to have found in libraries and monasteries. Included on his setlist were ‘lost’ pieces by Bach, the never-not-amusingly-named Pugnani, and also someone called Vivaldi.

Kreisler, below, had written the music himself, and lied because it offered the best chance of getting his own work heard (and also because he enjoyed a gag). The deception might well have gone undetected if a New York Times critic hadn’t casually asked him in 1935 about authorship and he fessed up, saying, “The name changes, the value remains.” The scandal caused debate (it made the front page of The New York Times), but Kreisler’s reputation remained intact. He died in 1962 regarded as a fine violin player and composer, and also as the man who raised Vivaldi’s name – if not his music – from the dead.

One person who was presumably fooled by the hoax was a French violinist and music historian called Marc Pincherle. Intrigued by the ‘Violin Concerto in C major’ that Kreisler was playing, allegedly by Vivaldi, he decided to dig deep and find out more about the mysterious composer. From 1913 onwards, he dedicated his life to studying Vivaldi and his biography, published in 1948, is the source text for everything we know about the man nicknamed The Red Priest, because of his red hair and occupation.

Early on in Pincherle’s research, the other strange occurrence happened. In 1926, a music professor from the University of Turin was summoned to a monastery/school in a nearby town to value a collection of music that needed to be sold to pay for building repairs. The professor, Alberto Gentili, was handed 97 volumes, 14 of which contained works by Vivaldi written in his own hand. He may not have known Vivaldi, but he sensed a huge score – with one major problem; on closer examination, he realised half of the collection was missing, and there began a painstaking, four-year adventure to not just locate the missing volumes but to prize them out of an aristocrat’s hands.

The music – 300 or so concertos, 14 operas, five volumes of sacred works, and other pieces – had been acquired by the wealthy Durazzo family in the 18th century and passed down until, in 1893, it was divided between two brothers, one of whom bequeathed his half to the monastery in Piedmont. With private backers, the University of Turin manged to reunite the collection and the epic find began the process of putting Vivaldi back on the musical map. Other works in autograph and printed scores, including The Four Seasons, were subsequently unearthed or dusted off, and in 1939 Italian composer Alfredo Casella staged his now legendary Vivaldi Week, with the involvement of American poet Ezra Pound. Just like it had in the early 18th century, his music spread across Europe, here being given a major platform at the 1951 Festival of Britain.

A concerto is a piece for a soloist backed by an orchestra, usually in three movements. The Four Seasons is the first four concertos – all for violin – in a collection of 12 called The Contest Between Harmony And Invention, and although Vivaldi is now best-known for his concertos, in his time he was more famous for being a ferocious, world-class violinist and an opera writer/impresario. He was canny and entrepreneurial, and almost certainly a pretty shitty priest. He caused a scandal in his home city of Venice a year after being ordained in 1703 for refusing to say mass – because, he said, a lifelong condition that caused a “tightness of the chest” (asthma, it’s now assumed) made it impossible. And when, halfway through his career, his switched to opera and worked cheek-to-cheek with a prima donna called Anna Girò, eyebrows were raised again. He lived – innocently, he claimed – not just with Anna but her older half-sister Paolina too, and they travelled with him as part of an entourage when he staged operas out of town.

Vivaldi’s father Giovanni dabbled in baking and in barbery before becoming a professional violinist, and the only musical child of nine that he had with his wife Camilla was Antonio, their eldest son. In Italy then, it was perfectly normal for the oldest boy to train as a priest – for solid work and to bring respectability to a family of modest means – and it was also usual for priests to have second careers. Vivaldi was first trained as a violinist by his dad and they made for a striking pair when they later performed together. Both red-headed, they were listed as a tourist attraction in a guide book from 1713.

Before that, when he was 26 and recently ordained, Vivaldi got a job as a violin teacher at an orphanage in Venice, Ospedale della Pietà (Devout Hospital of Mercy), and, perhaps unexpectedly, it proved to be his making. Girls there were encouraged to play music and in their ranks were some crack players. Vivaldi taught them, wrote for them, and turned them into a Venice-wide sensation. Their performances, which took place behind screens, raised money for the orphanage and fascinated local folk.

In 1716, Vivaldi was promoted to musical director of the orphanage, but his relationship with its governing body was fraught. Rather than being offered a job for life, he needed to be voted back in on a yearly basis and, more than once, he was booted out. However, even when he was elsewhere, he wrote for the girls – for money, and also because it provided a platform for his work. Of the 500-odd concertos he composed, a majority are assumed to have been written for the Ospedale della Pietà ensemble over a 30-year period, including The Four Seasons, which he’s thought to have penned around 1721 or 1722 while working for the governor of Mantua, 100 miles from Venice.

Just like today, musicians in 18th century Europe made money by signing publishing deals and Vivaldi’s favourite publisher, Estienne Roger, was based in Amsterdam. Roger printed The Four Seasons in 1725, after it was first performed, and he did so with four sonnets – one for each of the seasons. In the sleeve notes to the Neville Marriner (above left) recording, it says, “The concertos’ dedicatee, Count Morzin, heard the music before he read the sonnets, so we know Vivaldi did not mean them to be listened to exclusively as illustrative music – they can perfectly well stand on their own,” and that’s very true. The music is wildly imaginative, but the sonnets really aren’t; they’re merely descriptive, and possibly written by Vivaldi himself.

If they are Vivaldi’s work, they do at least provide some clues to the music’s intention, outside of, “This bit is meant to sound like a dog barking, and that bit like chattering teeth.” What’s incredible and gripping about the four concertos is quite how poisonous they can sound. ‘Summer’, you might imagine, would be soft and pastoral, but it’s full of tension and foreboding, telling the story – according to the sonnet – of some shepherd who, first, gets roasted by the sun, then a storm brews, then he gets savaged by gnats and flies, before eventually being dumped on by mighty rains, which flatten the crops. ‘Autumn’ is just as brutal, recounting a hunt in which “the beast, wounded, threatens / Languidly to flee, but harried, dies”. And bleakest of all is ‘Winter’, which flips perspective between those “trembling from cold in the icy snow” and some smug man who’s inside in front of a fire, then back again to the poor bastards outside who, walking on a frozen river, “slip, crash on the ground and, rising, hasten on across the ice lest it cracks up”.

It takes an exemplary ensemble to handle the operatic drama inherent in The Four Seasons and that’s why I love Neville Marriner and the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields’ 1970 recording, which features Alan Loveday on solo violin. It’s bright, but taut and modern, and according to Norman Lebrecht’s 2007 book, Maestros, Masterpieces And Madness, laid down after a session in the pub: “On their return from lunch, several musicians seemed visibly the worse for wear. On the red light, Alan Loveday, the New Zealand-born leader, took up the fiddle and played without pause for 40 blistering minutes. His one-take wonder hit the racks with a rush and started selling in shoals. It made the Academy Britain’s most sought-after musical export and Vivaldi a dinner-party accessory for aspiring hostesses the world over.”

Vivaldi’s career began to stall not long after The Four Seasons was published and became a hit across Europe, especially in Paris. Ironically, it was the form he pioneered – the concerto – that contributed to his downfall, as other composers took his ideas and ran with them in interesting new directions. Vivaldi couldn’t keep up and, forever the eccentric cleric, he was suffocated by the church too, who scuppered plans he made late in life to stage an opera in Ferrara. He lost a fortune in costs and was later forced to sell off his manuscripts at appalling prices, rather than getting them published with the promise of an on-going fee. No one knows exactly why he left Venice for Vienna in 1739, or why it took him a year to get there, but he was probably looking for work. He died in the city in 1741, aged 63, of “internal infection” and was buried in a pauper’s grave.

Even in his second life, Vivaldi was controversial. Stravinsky, a modernist, said in 1959, “Vivaldi is greatly overrated – a dull fellow who could compose the same form so many times over.” From someone with the stature of Stravinsky, it was a weird thing to say. Vivaldi certainly wasn’t dull; he was flamboyant and original, and although a lot of his 500 concertos are a bit samey, it helps to remember the circumstances under which many were composed – under contract to the Ospedale della Pietà at a rate of two a month, for one imagined performance only, and with absolutely no thought to them ever being later forensically examined by future musicians and scholars alike.

Since Stravinsky’s statement, Vivaldi’s star has only risen higher. His operas don’t get performed often, but his sonatas and sacred works have come more and more into focus. They can make for stunning, blissful listens, so I’ll leave you with two recommendations: if somebody decent has recorded a Vivaldi album that isn’t The Four Seasons and you see it in a charity shop, definitely buy it, and also grab any music by the great Neville Marriner, who died last year, and his Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. They’re still going, led now by American violinist Joshua Bell, but it was under Marriner that they became a powerhouse chamber group capable of consistently making classical music sound effortless and vital on LP.