All album sleeve art reinterpretations by Sean Reynard

“My God… it’s full of Star Wars fans.”

As soon as I start walking across the plaza of Utrecht Centraal, I become aware of them; cloaked figures at the periphery of my vision. Scuttling. Lurking.

What were those two tiny, cowled humanoid forms zipping past Kantorentum and Bloemenplaza into the shadows? SunnO))) are in town playing Tivoli Vredenburg as part of Le Guess Who? festival tonight; perhaps I just saw their two youngest fans already in costume.

I catch sight of the figures momentarily again. Tell me that wasn’t two fucking Jawas wearing backpacks and drinking cans of Coke.

I can just about hear the train announcements echoing up from the concourse: “Den Haag Centraal… Amersfoort Schothorst… Baarn… Eindhoven…”

A high pitched voice cuts over: “Hootini!”

I spy another Jawa and chase it through the uitgang where I emerge blinking into the November sunshine. Ahead of me a youthful Princess Leia, hair plaited and coiled into bagels and a youthful Luke Skywalker, dressed in beige moisture farm clothes are walking down the huge concrete flight of stairs toward a long straight footpath. At the other end of the path is a gigantic, blocky building with brutally straight edges. It sticks out of the ground, as if the Borg Cube has crashlanded right next to Utrecht’s train station. Luke and Leia start walking toward it.

“This is illogical”, I think.

Jaarbeurs (which means ‘yearly fair’ in Dutch) is a huge conference and exhibition centre which covers more than 100,000m² and is topped by an air hangar-like roof. And for the last decade this giant utilitarian structure has been home to the world’s largest event of its kind, The Mega Record And CD Fair which takes place every November and April.

I have to walk through a massive antiques fair and flea market to get to the area selling vinyl and after passing countless stalls selling enough vintage tat to fill up the British Museum ten times over, I eventually reach a section at the back of the hall selling nothing but records. The fair is big but nothing I can’t get through in a full day if I start now, don’t take lunch, skip the classic rock and punk and move very quickly. I ask a man sitting behind a small table selling record fair T-shirts where the admin office is and he immediately puts me right: “You know this isn’t the record fair right? This is just the overspill. The actual fair is through that archway there…”

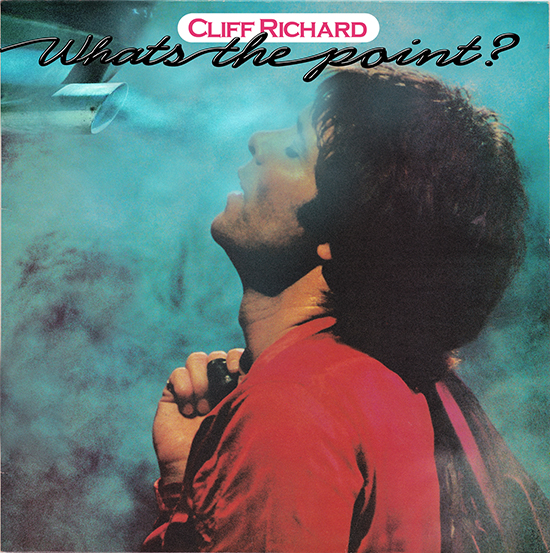

When I enter the actual record fair itself, it doesn’t resemble anything from Star Trek: Next Generation, 2001: A Space Odyssey or Star Wars but does in fact mirror the closing scene of Indiana Jones And The Raiders Of The Lost Ark. It is a dizzyingly huge space that boggles the senses; but rather than legendary occult artefacts that can be used as weapons which have been rescued from the Nazis, it is piled to the rafters with tens of millions of Cliff Richard picture discs. I literally can’t see the other end of the hall and I’m starting to fear that this is because it disappears out of view due to the curvature of the Earth…

The brain-mangling structure is starting to make me feel physically ill. I seek refuge in the admin office and talk to the organiser Cas Bosland. It seems facile to ask it but is it definitely the biggest one in the world?

“You should never ask the organiser because he’s always going to say yes”, he says before adding, “But yes it is.

“I’ve been all over the world and have never seen anything as big as the Utrecht fair, even in America. The next biggest one I’ve seen to this, would have been ten years ago in Barcelona or the one held in Austin Texas. And they are not even one fifth of the size. There were probably 150 dealers in Texas. Here we have 550 dealers from over 50 different countries.”

The stats are pretty impressive it has to be said. There are dealers from every continent bar Antarctica. The space covered is the size of two and a half football pitches or 12,500m². There will be 35,000 visitors to the fair during the two days it is on and they will shop at 433 stalls. There is no real way of counting how many records there are on sale here but Bosland’s educated guess puts it in the two – four million disc range. He once saw a copy of The Beatles (The White Album) with an issue number of 0000007 go for £24,000 and The Sex Pistols’ first single on A&M go for £9,000.

I mention the massive antiques fair I had to walk through to get to the record fair and ask him if there is something specific to the Netherlands that fosters a collecting sensibility.

He says: “Dutch people are known as being collectors. We organise the vintage fair, the antiques fair, the science fiction fair and the film fair as well as the record fair. But really it is the same thing – vinyl has become the new antiques… finally. People don’t collect stamps any more. Collecting has grown up with the pop culture generation and older people tend to collect what they liked when they were young. This means antiques are getting less and less popular as more and more people want to collect records.”

Sensing that I’m floundering, Cas gives me a floorplan as a parting gift. The main hall is divided into three zones: Metal/Punk/Alternative; Golden Oldies/Progressive/Beat; and Dance/Black Music/House. As I cut across all of the sections I seem to have wandered into some kind of torrid, slightly narcotic daydream. Stalls display ‘trophy’ LPs on their walls to attract wandering eyes. Everywhere I look there are long out of print Annette Peacock LPs, Mayhem picture discs, lurid Brainticket vinyl, the original, now slightly rusty Metal Box, eye-wateringly expensive Afrobeat originals, belly dance disco LPs from all over the Middle East, the whole history of techno on vinyl laid out before me…

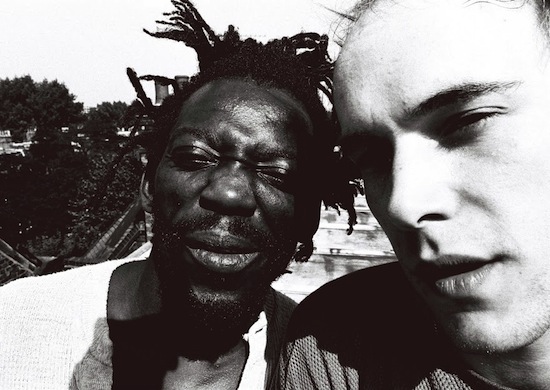

Midway between “progressive” and “black music”, I find Andy Votel, Doug Shipton and their DJ mate Boney running the Finders Keepers stall. A bunch of men in nice trainers and interesting T-shirts, still just on the right side of middle age, are all sticking their noses into some ancient looking record.

“Smell that!” Andy is shouting to some bemused punter. He spots me. “John, smell this.” I put my nose to the copy of Le Regine OST by Raymond Lovelock and inhale deeply.

“He’s Italian, it’s a Japanese LP yet it smells American”, he says triumphantly before adding: “Have you sussed out the vibe yet? Italian dudes are all over there. Swedish dudes are all over there.”

He waves his arm through an arc like a weather vane indicating a large section of space: “That’s prog down there. Punk and metal way over there. If you want to buy Spanish Cliff Richard bootlegs, go over there. Afrocentric stuff over there and don’t bother going over there.” He shakes his head sadly and mutters something about The Beatles and the Sex Pistols.

This is his tenth year at Utrecht and fifth running the stall and it’s clearly something he takes seriously. He explains: “One thing we didn’t want to do was to just come here and sell Finders Keepers reissues – if you do that, I kind of think you’re abusing the heritage of the fair. So it was important for us to sell original records… old Vertigo releases, obscure Italian soundtrack LPs… but to make sure we actually sell them and not just display them. There’s something that I hate in record collecting – you’ll see a lot of it in this room – and that’s trophy collecting. It’s bullshit and it changes what the game is about. There is no punk aesthetic to trophy collecting. Vinyl is a second class format and always has been and that’s the beauty of it. But the thing is, it’s a leap to let things go…”

I ask him if some of the discs on sale at his stall are from his own collection.

He says: “Some of them are my own; some of them are my prized possessions. Roughly speaking these days I’m on a one-in one-out system at home when it comes to vinyl. My philosophy last week was, ‘I’m going to Utrecht to sell all of my records and buy a whole new collection.’ The thing is, you don’t learn anything keeping these records on your shelves and not playing them. And nobody’s got the time to play this many records. So now I’m treating selling records exactly like DJing. I’m getting the same buzz from selling records as I get from buying them. Selling a record to someone who’s never heard it before is the same as getting a full dancefloor to me. You can work and work and tell someone everything about this record and they’ll just walk away and buy some bullshit splatter vinyl horror reissue instead and that’s the equivalent of DJing in All Bar One to me…”

I tell him that this is all fair enough but that I’m probably going to buy a couple of reissues while I’m here. In fact as soon as we’ve finished chatting, I’m going to buy the Holy Mountain soundtrack directly from him…

He adds: “Well, yeah, I’ll happily buy a really well done reissue where the original never really came out or now costs £2000 but I’m not going to buy… fodder. I like to think that most reissues on Finders Keepers warrant the release because they’re so hard to come by. Masahiko Sato’s Belladonna… Jesus Christ, that is an album that warrants a reissue. 90% of what we release has never even been out on vinyl before.”

There is a lot to be said for having nicely packaged records that haven’t been used as drinks coasters, placemats or bifter rolling stations at any point in the last four decades. And there is a massive amount to be said for LPs that don’t sound like they’ve been remixed by Burial when you drop the needle. Some people can be sniffy about this and claim that the format has nothing to do with the music but it really does… for me at least. I tell Andy I’ve had the Tartan Jodorowsky box set for a good few years now and it has both the El Topo and the Holy Mountain soundtracks on CD as part of the package. And yet I’ve never taken them out of the box. I want the FK reissues because of the great artwork and the sleevenotes.

He nods: “I think the best thing about the FK reissues, without wanting to blow our own trumpet, is the notes. We were working on this project for maybe ten years before the Tartan box came out. When the Tartan box came out (2007), they told us we definitely couldn’t do the music. Three years went by and I sent them an email saying, ‘Look, if there’s any help we can give you with the sleevenotes or artwork, I’d love to be involved.’ At which point they sent us back an email saying, ‘Ok. You can do it.’ So as soon as we got the green light I started doing the research and our sleevenotes tell a story that no one ever knew. Even the people who play on the record didn’t know the story of the soundtrack. But the American version of the soundtrack includes a synopsis of the film. Who needs that? I don’t need that – I’ve got the DVD. [LAUGHS]”

He picks up an armful of albums off the FK stall and we set off for a stroll. As we walk up and down aisles he gives me some advice on how to operate inside such an overwhelmingly large environment. Looking over my wishlist he notes Insertion In Middle ‘C’ by Dr. Philter Banx – a fruity 1975 cosmic disco, new age sex music album from Canada and says that it’s important not just to check where the artist is from but where the pressing originates from. In this instance it’s also a Canadian pressing so I need to head back to the ‘Progressive’ quarter and then visit the two Canadian dealers in this section first and foremost.

Every so often Andy stops by a stall, engages in a lengthy conversation with a dealer and then hands over a number of records from under his arm in exchange for other discs from their stall. In the half an hour I’m with him he does this maybe ten times. The scale of these exchanges is bewildering and complicated. He always has the same number of LPs under his arm as we walk along chatting but I get the impression that the value of what he is carrying is going up incrementally with each fresh exchange.

He then confirms my suspicions that he is actually the maverick Second World War profiteer character, Milo Minderbinder, from Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 when he says: “The finances were really tight last year so I came here with literally no money. I had to borrow cash to get here and by the time I’d bought my lunch from a service station I had €20 left. So I went out and bought two library records for €10 each, came back to the stall, flipped them both for €100 each and that was it, I was off. It all came down to having the listening deck on the stall. People from that older generation who don’t have listening decks are a bit lost now really because that try before you buy thing didn’t exist when we were kids.”

He takes another look at my list and sees the rather vague phrase: “Turkish Funk And Disco.”

He rubs his hands together and beckons me to follow him: “I’ll introduce you to some people who sell Turkish records.”

I’m starting to sweat a little bit now. I’ve DJ’d with Andy before and I know he’s got enough Turkish vinyl to do a 24 hour set should he wish – which is no surprise given the numerous Anatolian psych and dance compilations he has put out, not to mention the anthologies of artists like Ersen and Selda that have been released on FK. I’m a complete neophyte and dilettante and now I’m about to have my arse handed to me by a bunch of braniac record collectors who have been doing this professionally for decades.

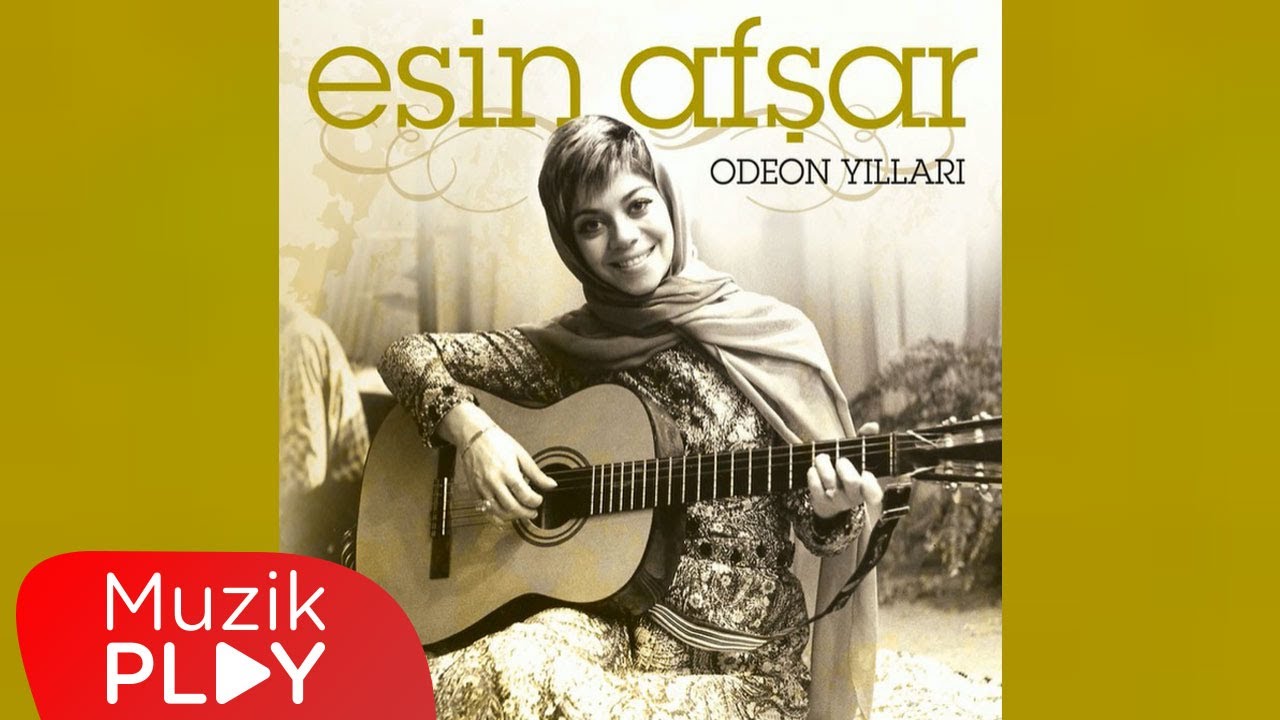

Andy introduces me to Fred Kramer of the Belgian DJ collective Radio Martiko – I want to run somewhere far away where there are no circular black discs in sight – but instead I find I’m being given a massive pile of ancient looking, expensive 7”s from the Middle East and being pointed in the direction of a comically small record deck and a pair of battered headphones held together with masking tape. How I wish I was at home with my Phonica and Discogs sourced Turkish edit 12"s, not having my ears tasked like this… Although edit bootlegs are easy, however, they are also frustrating releases as they often don’t tell you what the names of the original tracks are… you can’t help but wonder what the tracks would sound like if they weren’t bolstered by a rigid beat or if they hadn’t had some extra, synthesized bass added. And just as I’m whistling the electric saz line of one of these nameless tracks to myself, I drop the needle onto the groove of a particularly fucked looking 7”… and exactly the same music, in exactly the same key, plays back to me through the headphones. I wait until the threat of gibbering or fainting passes, check the label surreptitiously and turn to Fred saying: “Ah, Esin Afşar – ‘Zühtü’. I’ve been looking for this for ages…” I hand over some cash and suddenly the room feels ever so slightly smaller and it’s as if some weight has lifted from my shoulders.

(I leave this here without comment as a warning to others. After all: this is how it starts. Just when you think you can’t descend any further down the vinyl staircase, you realise that you’ve only just begun taking your first few faltering steps…)

I go to say goodbye to Andy. He’s got more perplexing international record exchanges to take part in (“I’m just after Japanese jazz this year, which I’m probably going to get from Swedish and Italian dealers. Japanese dealers are only good for ABBA and The Sex Pistols for some reason.”) And I’ve just spotted a German stall that seems to be selling nothing but Coil and Nurse With Wound vinyl; and this is where our sonic interests probably diverge.

As a parting shot I ask him how important Utrecht is to him now and he replies: “I’m turning into one of those guys who just buys all of his records here. About a month before Utrecht, I start getting the vinyl bug to buy loads of records and I think, ‘Ungggh. If I go to Utrecht I won’t have to pay for postage.’ So I go to Utrecht and buy a load of records. And then that will probably be it for five and a half months – until it’s time to start preparing for the next trip to the Netherlands. It’s like when Spock has to go back to Vulcan every seven years to mate.”

It’s now eight hours since I arrived and all the stall owners are starting to pack up as I head for the exit and I spy a long row of trestle tables mobbed by people in Star Wars costume. About thirty actors from all seven films are signing autographs. I’m pretty sure I spot Warwick Davis, the British actor who played Wicket the Ewok chatting to a bunch of Jawas.

If you hang around long enough, eventually everything becomes clear.

BACK CATALOGUE REISSUES OF THE MONTH: African Headcharge – The First Four Albums

Just after I turned 19, David Lynch’s road movie revamp of The Wizard Of Oz, Wild At Heart, went on general release and I went to see it three times at the pictures in Hull in one week. Despite being generally dismissed as garbage at the time, there was, I felt, a lot about it to recommend repetitive viewing of the film. I was particularly taken with one peculiar scene in which three hired assassins carried out a contract killing on the well-meaning but ill-fated Johnnie Farragut (played by Harry Dean Stanton). The terrifying trio included handsome blacksploitation veteran Calvin Lockhart as Reggie and Lynch regular Grace Zabriskie playing the demented killer in calipers, Juana Durango. Of all the horrific bloodshed and mayhem in that film, there is nothing quite as disturbing as Juana’s screamed ullulations as she prepares for sex with Reggie… while he in turn prepares to shoot Farragut in the head.

However, little did I know that this was actually a much tamer version of the scene than the one originally shot by Lynch. In the initial, longer sequence, the sadistic treatment of Farragut caused mass walk outs in two test-screenings; which in turn caused Lynch to realise that the scene was “strangling the film”.

The unpleasant, disturbing and sexually charged energy this scene possesses is amplified by the raw, cavernous dub music, with its sick-sounding slurring vocal track playing in the forefront of the mix as the scene unfolds (as if to suggest that this isn’t non-diegetic soundtrack but actually the ear-rattling music that the killers listen to while carrying out their work). The springily reverbed bass echo causes the uncomfortable sensation for a fleeting second or two that you might actually be in that horrible cellar with Farragut and three maniacs.

During the Summer of 1990 I had been taken under the wing of some, older crusties in Hull who were disabusing me of the idea that all reggae-related music was terrible. In fact they were actually helping me to explore the idea that a lot of modern dub was, in fact, fantastic. They did this primarily with the aid of a stack of On-U Sound vinyl and a lot of ganja. It has to be said that out of all of the records they introduced me to that summer, Lee Perry’s Time Boom De Devil X, Creation Rebel and Dub Syndicate were a much easier sell than African Headcharge. At first I didn’t know what to make of this stark, spacious, experimental and almost austere dub but I was blown away during one hazy session when I realised that I was listening to what sounded like the incidental music from the Wild At Heart torture scene. It was indeed a ‘version’ of the same track, ‘Far Away Chant’ from their debut LP, My Life In A Hole In The Ground originally released in 1981.

Of course heard in isolation from the film, this track, and the rest of the album, wasn’t some nerve shredding industrial bass fest, although there were still moments of pure dread lurking in the shadows to horripilate the chemically relaxed and unsuspecting. Check out the unsettling, glitchily recorded vocals of King Cry Cry (Prince Far I) and the speaker traversing whale-song noise that’s recast as an Evil Dead-style demon howl on ‘Primal One Drop’. But mainly this is a broadcast sent from the outer perimeters of dub just before the advent of affordable sampler culture.

Listeners (especially of the young, foolish and pot-addled variety, like I was) were perhaps being invited to consider the inauthenticity of world music – the title is a clear reference to David Byrne and Brian Eno’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts – even though this was a much rootsier album than anything else I had then come across on the label and aspects of it sounded very ‘authentic’ indeed to my ears. In A Hole came out just months after Bush Of Ghosts, and celebrated Eno’s “search for psychedelic Africa” while gently lampooning African Headcharge’s more modest budget. The titular hole in the ground was in fact the very modestly decorated and fitted out Berry Street Studios situated in a basement in Central London. But as with a lot of notable dub excursions over the years, necessity seems to have been the mother of invention.

The thing that anchored the project in a clear heritage of both Jamaican and African music was the incredible percussion of Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah, who had studied drums at a Rasta drumming camp in Wareika Hill under Count Ossie (he who produced Grounation with The Mystic Revelation Of Rastafari and Tales Of Mozambique, the latter recently reissued by Soul Jazz). Over a bedrock of drums and bass, he was given the space to create percussive patterns that were by turns intricate and thunderous while Adrian Sherwood was left free to orchestrate a fluctuating band of collaborators into improvisational exploratory sorties into uncharted territory as well as spiritual jazz and post punk.

I never like making special pleading for vinyl even though I hoard the stuff; because I also hoard CDs, MP3s and cassettes as well. However I have to say that, finally, after three or four years of saving up and buying pieces here and there, I’ve finally got a new stereo system set up at home (I’m going to try and salvage the last few tatters of my dignity by not listing the components here) and these records sound just great on it played on these new wax reissues. You won’t often hear me saying this (as I genuinely don’t think it’s that important half the time) but given the amount of luxurious depth these recordings offer, it would be a shame to listen to them on a Crossley or through laptop speakers or on earbuds and for me at least these fabulously recut slabs of wax are the way they’re meant to be listened to.

Erasure Reissues – The First Three Albums

I heard the noise first.

It was a soft, regularly recurring popping sound, gradually getting louder; as if a distant steamroller were driving slowly in my direction along a road made from bubble wrap.

It was June 3, 2005 and all down my street men were reading an article in The Times and then their heads were blowing up in a Scanners-style explosion of blood.

Caitlin Moran [Blatt!] had suggested that Erasure [Blatt! Blatt!] were better than Kraftwerk! [BLATT! BLATT! BLATT! BLATTY FUCKING BLATT BLATT!] And then she brought gender, race and sexual orientation into it and it was game over – you couldn’t hear anything for the sound of (straight, white, male) heads exploding in rage for the rest of the week.

"Let’s face it — there is nothing Kraftwerk did that Erasure didn’t do better, for longer, and while wearing a blue sequinned cowboy hat and chaps."

It was such a bravura piece of challops that I’m still slightly in awe of it now a decade later. Despite being a fan of Erasure I remember almost blowing my own top before thinking to myself, “Well, hold on a second… if you actually think about it and pit ‘Ruckzuck’ against ‘Who Needs Love Like That’ and ‘Vom Himmel Hoch’ against ‘Oh L’Amour’ then Wonderland probably is better than Kraftwerk and I don’t even need to check the track listing of Kraftwerk 2 to know that it’s not as good as The Circus. How about The Innocents versus Ralf And Florian? Hmmm, maybe… Let’s scroll forward a few. How about Trans Europe Express versus I Say I Say I Say. No! You’ve gone too far! Wait a second… why is my forehead bulging outwards? Aiiieeeeeeee! BLATT!”

(The article is still available online but now lives behind The Times’ paywall, which is probably just as well for the sake of the spatial integrity of the heads of music spods everywhere.)

Was it fair to suggest that uptight male Kraftwerk fans couldn’t handle some out and proud gay synth pop? After all, it’s not like Pet Shop Boys, Soft Cell and Coil aren’t wreathed in hipster kisses; and many other critically tolerated groups, such as Tubeway Army, Human League and, perhaps, Depeche Mode have been identified as queer or (non-normative at the very least) at one time or another. Probably not 100% fair then but then that wasn’t the main thrust of what was being said as far as I can remember. Operating in a genre where an outsider narrative was the norm, Erasure’s complete refusal to dress their music up in the borrowed robes of alienation, the occult, pop art, decadence or anything else was itself a truly militant stance in relative terms. The main thrust of the article for me was actually a killing blow aimed straight at the heart of the (traditionally but not exclusively) male way of discussing music as a conversation avoidance strategy – comparing, listing, ranking, with no real insight to speak of; not to mention the knee-jerk tendency to dismiss any music that can’t easily be intellectualised.

“There’s no clever narrative to these records to speak of… I’ve been forced into a position where I have to discuss how they make me feel… BLATT!”

As per, it’s not difficult to find these albums in second hand shops but the remastering is so crisp and the packaging so luxuriant on these three reissues that I’m taking the relatively unusual step, for me, of consigning my original copies to the charity shop and keeping these instead.