2015 may come to be seen as a watershed in the gradual erosion of the UK’s small-scale music venues. Over the last 12 months, we’ve seen a frightening number of vital underground spaces across the country either close, or be threatened with closure: from Plastic People in January to Power Lunches in December; clubbing institutions like Glasgow’s Arches to rock & roll landmarks like Manchester’s Roadhouse; large Arts Council-supported mainstays like Rich Mix to tiny basement dives like People’s or Club 414. Across the UK, but particularly within London’s ongoing and extravagantly deranged property bubble, the picture has been grim.

While this is by no means a new phenomenon, 2015 has felt particularly bleak, with small venues’ prospects looking more precarious now than at any other point in recent memory. In September, the Music Venue Trust published a report indicating that 35% of London’s grassroots music venues had closed since 2007. A report by the Association of Licensed Multiple Retailers reveal similarly depressing figures for the UK’s nightclubs, half of which have closed in the last decade. Seeing these cumulative losses presented as one lump sum is stark and depressing.

Partly, this is just economics: independent venues are more likely to occupy pockets of the city with at least some identifiable cultural capital but less prohibitive property costs, placing them squarely in the crosshairs for gentrification and redevelopment. Likewise local councils, facing deep cuts to their budgets, seem increasingly risk-averse when dealing with the night-time economy. Why spend limited resources on supporting music venues, when restricting them can reduce strain across licensing, policing and elsewhere? Hackney Council’s recent decision to drastically restrict license approvals is a case in point: such a policy might not immediately lead to large numbers of venues closing, but the overarching priorities seem worryingly clear.

The pressures on independent musical and cultural spaces are also symptomatic of more fundamental threats to under-represented and marginalised groups within society. There’s the soft bigotry of rhetoric around “British Values" and the like, implying that cultural worth is singularly-defined and divergence fundamentally suspect. This is frequently paired with the erasure of local areas’ cultural identity or access to venues when existing communities are priced out, discriminated against or excluded from local decision-making (often replaced by others who treat that heritage with ignorance or hostility). All this occurs against the background of continuing cuts to the financial and social supports people depend on simply to survive, let alone go out and listen to music. None of these problems disappear the moment a particular venue ceases to be threatened with closure, and all demand broader awareness. Even defining concrete terms is difficult: one group’s community space may end up marking another community’s demise.

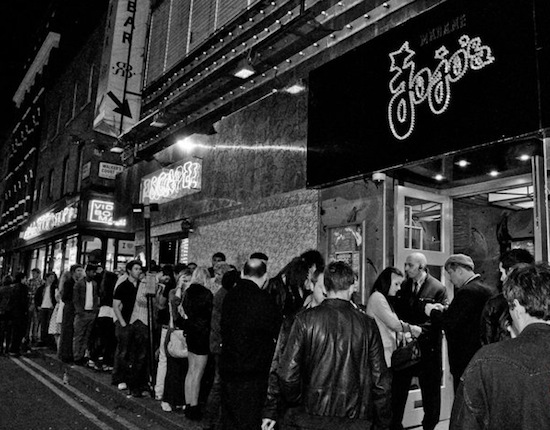

The fate of much-loved cabaret and club venue Madame JoJo’s embodies the conflict between artistic, commercial and social concerns more succinctly than most. Long an emblem of the lavish creativity lurking beneath Soho’s scruffy veneer, its license was permanently revoked by Westminster Council just over a year ago. On one level this was entirely predictable, after security staff were involved in attacking a member of the public with baseball bats.

And yet, digging into things raises a few questions: in their license review, JoJo’s managers underline their previously clean record, and claim a positive working relationship with the police. Their proposals for substantial new security measures were subsequently rejected by the licensing committee, in favour of revoking the license entirely. It’s hard to understand whose interests are served by permanently mothballing an immensely popular venue instead of working positively to improve or reform its management.

Of course, Madame JoJo’s fate had in fact been sealed back in December 2013, when the building owners Soho Estates (a property development firm originally founded by porn baron Paul Raymond) were granted planning permission to redevelop the area. Whether by accident or design, revoking Jojo’s license merely served to smooth the path for 2016’s planned demolitions. In their submission to Westminster’s licensing committee, Soho Estates refer to these redevelopment plans, reveal that they’ve already begun their own legal action to evict the venue managers, and warmly welcome JoJo’s license being called in for review.

They’ve since promised that a new version of Madame JoJo’s will return to the redeveloped site <a href="http://www.thisiscabaret.com/official-madame-jojos-will-re-open-in-a-couple-of-years/“ target="out">“in a couple of years’ time", but the security of that promise, or the precise form any new venue might take, is unclear. Soho’s seedy reputation is allowed to act as an edgy backdrop for a promotional campaign starring Raymond’s granddaughters, but any genuine traces of the area’s complex history appear to be undesirable.

It’s difficult to gauge Westminster Council’s attitude amidst all of this. They were keen for me to note that they “remain very conscious of the cultural significance of Madame JoJo’s, and would welcome the venue rising again under new management": this may well be true, but it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that any good intentions must ultimately have wilted under the glare of financial concerns, police criticism, and wealthy local interests. Perhaps this confluence of inter-connected pressures helps explain the shocking numbers of venue closures elsewhere, too.

2015 has also seen new venues and events springing up to fill the gaps created by others closing, but it’s worth considering what form those venues have taken, and what those forms embody and represent. Most visible has been the pop-up, which in a few years has gone from innovative to ubiquitous, co-opted in 2015 by everyone from the National Trust to Jamie xx.

Ephemeral and opportunistic, pop-ups at first seem to draw on the same lineage as free parties or squat raves, repurposing unwanted spaces to create something daring, disruptive and unburdened by red tape. The reality is often a bit different: as outlined in this excellent article by Dan Hancox, pop-ups are just as likely to be a vector for larger corporations to make use of cheap rents and some vaguely rebellious branding. Even when that’s not the case, many pop-ups are still a poor replacement for spaces which more naturally emerge from or respond to a specific community’s needs. Their finite lifespan demands a quick and direct route to profitability, which perhaps explains why so many of them veer towards universal feel-good fodder: an ocean of barbeques, cupcakes, and cocktails, pop culture references, and cheerfully bland infantilisation of a ball pit for ‘adults’.

Near where I live in South London, a disused space originally earmarked for the “Grow Brixton" project and intended to focus on community groups and environmental sustainability, was launched earlier this year having been rebranded as Pop: Brixton, now run in conjunction with property developers The Collective and hosting product launches for Adidas. Pop have since been granted permission to redevelop a multi-storey car park in Peckham, previously home to Frank’s Bar and the Bold Tendencies arts organisation. Bold Tendencies’ own proposal for the site, built around 800 affordable artists’ studios and Peckham’s long-term creative sustainability, was rejected in favour of Pop’s focus on “pop-up retail and a multi-use events space". Pop-ups become, in Hancox’s words, “a gloss of fake ‘community’ painted over the cracks rippling through Britain’s social structures".

In this, the pop-up also ties in neatly to the other noticeable trend across the summer of 2015, namely a loosely-themed “experiential" approach to music events. Writing in August, Clive Martin sums this up as:

A club culture that’s affluent but not gaudy, urbanised but certainly not intimidating, often utilising reclaimed, picturesque city locations such as rooftops and riverside spots. These events often have sideshows involving corporate sponsors, street food stalls, marquees, competitions, generic wedding-playlist DJs and all sorts of additional activities on top of the old staples: getting fucked and dancing.

The same themes seem to be at play here as with the pop-up: as the outlook for traditional bricks-and-mortar spaces becomes increasingly bleak, venues are defined less by the communities they represent than by a set of easily-digestible and inoffensive lifestyle activities attached to them.

Not every new venue conforms to these stereotypes, of course, nor is it a zero-sum game between more traditional venues and temporary ones. Grassroots venues also aren’t perfect by any means: there’s room for many to be safer and more inclusive for marginalised groups, for example. Still, it’s hard to escape the feeling that music venues which define themselves by opposition to the mainstream, in whatever form, are disappearing at much the same rate that ones catering to a more homogenous, wealthy and sociopolitically disconnected audience seem to be prospering.

One particular day in 2015 sums up this contrast with almost poetic efficiency. On 11 November, it was reported that the Bussey Building in Peckham, home to a multi-floor music venue, arts café and record store, was facing closure due to a proposed residential development mere feet from their front door.

The risks to the site, originally saved from demolition in 2007 with the involvement of community group Peckham Vision, were clear: as one employee explained, “once the flats and shops go into the block, you can forget about the Bussey Building and about everything we do there, because nobody would be able to enter the building properly. It would kill us".

In the glossy planning document produced by the developers Frame Property, mention is made of an earlier “series of discussions with Council officers" about the proposals and, more ominously, the developers’ desire to work with the “current and future occupiers of the Bussey Building". As with so many developments of this kind, there’s an overwhelming sense of the application process as a mere formality, with the real meat of the issue agreed privately beforehand.

On the same day as the Bussey’s precarious situation was revealed, a new venture was launched via the equity crowdfunding platform Seedrs. Summerland, scheduled to open in December 2016, plans to build a “hyper-real tropical paradise" in the heart of East London, featuring DJs atop waterfalls, extravagant rainforest environments including a projection-mapped sky fading from day to night every 4 hours, street food, “fit lifeguards" and so on; an escape from the “grim" realities of London in winter, as they put it.

If the organisers had set out to embody the criticisms made by Dan Hancox and Clive Martin, they could not have done a better job of it. Summerland captures the breezy vapidity of a thousand rooftop discos, merged with some hefty equity funding and, predictably, a “secret venue" somewhere in East London (investors are allowed to see the exact location only after they’ve signed an NDA). The transience and infantilisation of the pop-up is expanded here to form an entire make-believe world, defined by an utter disconnect from its surroundings: it’s taken as read that the only sane response to London’s “grimness" is to ignore it completely.

Little if any of Summerland’s media coverage has noted that CEO Debs Armstrong and Communications Director Garfield Hackett, were also directors of the London Pleasure Gardens, which went into administration in 2012 after a disastrous launch, including the cancellation of that year’s Bloc festival. That collapse took with it some £5m of public money invested in the project by Newham Council, home to some of the highest poverty rates in the UK. When London Pleasure Gardens Ltd was dissolved in August 2012, its auditors Deloitte pocketed £400,000 (graciously reduced from £1m and paid entirely by the Council): from the documents filed at Companies House, it appears that there were no further assets with which to pay staff, suppliers, or to return taxpayers’ lost investment.

By contrast Summerland (a wholly distinct entity from London Pleasure Gardens) predicts annual turnover of £8m, profit of £3m and reserves of £7m by the end of 2020. Early corporate supporters include Virgin Atlantic and See Tickets, while £155,000 has been raised through their crowdfunding campaign (£148,000 coming from a single anonymous individual, somewhat undermining the “crowd" aspect of things). When asked whether Summerland will be engaging with their local community, Armstrong told me: “Summerland is a commercial, cultural and theatrical show, it is not a creative regeneration or community project nor is it working in those segments". Because the venue location remains secret, it’s not clear whether those “segments" include Newham residents.

Summerland is billed as being closer to something like Secret Cinema than the more straightforward events venue and community hub of the Bussey Building. Even so, the juxtaposition of these two projects sums up the strange inversions at play in 2015: grassroots cultural spaces intrinsically linked to their local communities have to fight relentlessly to stay afloat, while their local Councillors cosy up to property developers; at the same time, lavish experiential ventures are dropped into the East End with little mention made of the financial damage done to the local community last time around.

Thankfully, 2015 may have seen this lopsided state of affairs start to right itself: the aforementioned Music Venues Trust report on venue closures was in fact developed and launched alongside the Mayor of London’s office, via a dedicated taskforce set up at the beginning of the year to protect music venues. In many ways this is excellent and overdue news: detailed policy work is now feeding into a single-purpose body with genuine powers to create change in London, and potentially lead the way for other regions across the UK.

Again, though, the reality might be a bit more complicated. For one thing, Boris Johnson’s Mayoral reign has been defined far more by the flashy than the substantive: similarly glitzy launches for his money-guzzling and barely-used Dangleway, the proposed "Garden" "Bridge" (it functions as neither) and the half-cocked announcement of 24-hour Tube services all point to a policy agenda geared more towards burnishing London’s international brand, and feeding Boris’ own Prime Ministerial ambitions, than meeting actual need.

The most concrete power embodied in the Mayor’s new taskforce is the “agent of change" principle. This places a legal responsibility on people and businesses moving into an area to adhere to its pre-existing cultural and environmental norms: for example, requiring new housing built next to music venues to install adequate soundproofing to mitigate existing noise levels. In an ideal world, this could solve problematic situations like the Bussey Building’s in an instant.

The taskforce cites Australia in particular as a country where these “agent of change" rules have been implemented successfully. In reality, though, they’ve been far from a complete solution. As this superb piece by Andy Webb reveals, they’ve done little to protect Sydney’s club venues from a series of controversial “lockout" laws, prohibiting re-entry (even from smoking areas) to any venue after 1am. In the words of one club forced to close by the resultant drop in late-night business:

Small business owners lack influence and do not have a voice. The overarching agenda by conservative groups for Sydney is to remove late-night culture rather than acknowledge it as a core part of the cultural fabric that enriches a city.

Speaking to the Sydney-based author and urban policy analyst Ianto Ware reveals some of the complex issues behind this, and underlines the need to encompass a number of different policy areas (several of them, in London’s case, outside the Mayor’s direct control):

My home town of Adelaide introduced an “agent of change’ principle in 2001. It didn’t work as well as we’d hoped. The problem was that it didn’t flow evenly across all the related policy frameworks. Whilst the Agent of Change principle was within the planning system, it didn’t flow on to other pieces of legislation, like environmental pollution.

Residents found that they couldn’t complain through the planning system, and shifted to using environmental protection legislation to have venues classified as an emitter of noise pollution. Without clear definitions as to what ‘pollution’ meant, it became incredibly easy to lodge ongoing vexatious claims and simply drag the issue out until the venue gave up and stopped hosting music. Ironically, this led to more bars with nothing to do but drink, and more anti-social behaviour.

One thing I’d recommend in retrospect is to treat ‘agent of change’ as a principle for the character of an area. If an area has a history of live music, performance and art, the regulatory framework that governs it should protect it. That means planning, licensing and environmental protection should all support cultural activity, but also that new developments should be required to include cultural infrastructure.

The "agent of change" principle has already begun to gain broader attention, with Labour MPs tabling an amendment to the Housing and Planning Bill which would enshrine these ideas in national planning law; Government ministers appear broadly sympathetic, but the need for further consultation suggests that it may be a while before any visible changes occur.

These top-down governmental solutions are only part of the picture, though. Following news of the threats to the Bussey Building, Southwark Council received over 1,500 complaints; Frame Property decided to “pause" their redevelopment plans before announcing in December, following a meeting with the local community, that <a href="http://peckhampeculiar.tumblr.com/post/134544576344/breaking-news-victory-for-bussey-building“ target="out">all plans for residential development on the site had been abandoned. Similar action may now be required to save another nearby venue: plans for a block of flats next to Canavan’s, a few hundred yards away on Rye Lane, were announced mere days after the Bussey won its reprieve.

Learning from grassroots successes like the Bussey Building, and those of broader anti-gentrification campaigns like Focus E15 and Save Cressingham Gardens, may ultimately prove to be more effective than relying on policymakers to advocate on our behalf.

As far back as the Criminal Justice Bill of 1992 and beyond, cultural spaces unable to state their value in purely commercial terms, or with reference to a narrow and easily-understood set of cultural benefits (predominately those catering to a middle-class and quietly parochial mindset) have risked being treated by local and national policymakers with ambivalence at best, and antipathy at worst.

Whether the starting point is Westminster Council’s professed good intentions, competing demands over the use of urban space, or more nakedly authoritarian initiatives like Form 696 (used by the Metropolitan Police to demand the names, phone numbers and addresses of performers at gig or club nights, and arguably targeted predominately at black and Asian audiences), the collective need for non-mainstream spaces as sites of refuge, self-expression, or Bacchanalian release is too often given mere lip service. For the most part, these spaces are permitted for only as long as they avoid impinging on more valued constituents: as soon as any meaningful financial or political sacrifice is required on their behalf, they are deemed an extravagance.

The struggle, therefore, is not only to defend individual venues, but also the principle that our access to them is fundamental. 2015 has revealed what might happen if that understanding is lost: an infinite selection of identical Keep Calm And Pulled Pork pop-ups, under an endless projection-mapped sky, in a city none of us recognise or care about any more.