The UK music industry is up in arms about the cost of Visas that enable artists and their crew to travel to the United States to play gigs. They’ve been up in arms for a while, and there are conversations going on between representatives of the Musicians’ Union and US Homeland Security. I hope these conversations bear fruit, and that the cost of US Work Visas is greatly reduced.

Actually, that’s not true.

I don’t care.

I don’t care because I don’t think the costs are particularly high. Sure, the application process is a pain in the arse, as is getting up at five in the morning to get to the US Embassy for your appointment, and the waiting around, the nervousness brought about by the US Embassy just being a generally intimidating place, and the further waiting around for their answer, plus the fact that they retain your passport, which can cause problems for a number of reasons (I learned the hard way).

But paying £282.03 per year to work in the US isn’t a lot of money.

I’m not getting a discount; that’s what it costs me, my artist, and our FOH Engineer each.

I’ve just read this page on the Musicians’ Union website, and the following quote is startling:

"The cost of a four-piece band requiring work visas and petitions can cost in the region of £6000, and that’s before any crew costs are also factored in."

I appreciate that sometimes radio or TV promo is lined up last-minute and YOU ABSOLUTELY HAVE TO GO BECAUSE IT WILL BE THE THING THAT WILL CRACK THE MARKET. In this case, sure, you will pay a premium, and I’ve had to in the past. But figures of £5,000 and £6,000 are being thrown around as the norm, and putting the shits up artists and managers with reactionary comment in the absence of context doesn’t help, and the MU should know better. Though when it comes to UK industry bodies arguing their cases, I should know better than to expect nuance.

The cost of a US Visa is expensive if you’re not going to make any money on your tour, (and unless you’re very, very lucky, you’re not) but so is the cost of flights, accommodation, crew wages, and all your other outgoings, including those baggage trolleys at JFK ($6 each, non-refundable). And there’s the small matter of Withholding Tax, where the promoter will keep 30% of your fee to pay to the IRS. Withholding Tax is a bastard if you can’t find a way to reduce or offset it.

In November of 2015 I was asked to contribute to a Consequence of Sound article on the subject, which you can read here, and the journalist, David Sackllah, emailed me some questions on the issue. He wondered if I considered the Visa application process prohibitive. I said it depended on your level of determination. The application process isn’t prohibitive at all if you really want to go. The Visa application result can be prohibitive. "Your Visa application has been denied" is a fairly prohibitive statement.

The application process is opaque and onerous (given a choice of the two, I’d rather see it changed than the cost reduced) but there are many things you can do to improve your chances of success:

- Be absolutely sure that going to the US is the right thing to do. I’m a total sucker for that country. I’m in thrall to the cinematic romance of it, of its mythology; the Pacific Highway, the colours of a New England autumn, the view from the Griffith Observatory. But that doesn’t mean I should try and work there, when there are many thousands of bands who live there who no one will care about if they pitch up at The Casbah in San Diego on a Tuesday night, never mind one from the UK. I did it once and seven people turned up. We could choose to tour Eastern Europe instead, but let’s be honest with ourselves; we’re not driven by a longing to eat kalduny at a roadside cafe on the E95 between Belarus and the Ukraine in the same way we romanticise a pastrami sandwich in Katz’s Deli, right?

- Be really, really sure. It’s an enormous country, it’s very far away, and it’s the toughest market in the world to break. Your chances are incredibly small. Run a budget. If there’s a deficit, how will you make it up? If you can, is it worth going? Is there enough interest in you there to justify it? You’re a small business and like any small business you need to make smart decisions. You don’t start making kids’ toys and go from selling them to your neighbours to exporting them to Japan in enormous quantities within the first three months. Go to the US when you think there’s a reason to go. Go when you can afford it, or when you can’t afford not to. Why not tour Europe instead? It’s closer, there are no visa costs and the production standards in their small venues are generally far better.

- Get expert advice. There are a few reputable visa agents, and a great many unreputable ones. Hire one that won’t fuck you over.

- Prepare well in advance. Months in advance. You’ll pay more for a ‘premium service’ if you leave it to the last minute, same as you will if you buy a train ticket from London to Glasgow on the day of travel. I appreciate that’s not always possible. Bear in mind there’s always a backlog around SXSW due to the volume of applications. Artists are allowed to play an official SXSW show without a visa, on the Visa Waiver program that SXSW have negotiated, but few UK bands are going want to spend thousands of pounds to fly in, play one show, then leave. Almost all want to do other shows in town and perhaps outside of Austin, to maximise their time there. US Immigration staff have got better at catching people. They can Google your band name and see your tour dates like anyone else.

- You’ll need to present a very strong case. It’s important to remember – and this seems to be totally lost on those who’re arguing for a better deal – UK bands aren’t being singled out by the US Government. There’s no conspiracy against bands; bands are just people doing a job, like graphic designers, doctors and scaffolders, and like them, bands need to prove the work they do can’t be done by a US national. Don’t take it personally if your application is rejected.

- You should know that the burden of proof for a solo artist (like any solo worker doing any job) is higher than for a group. A solo artist has to convince US Immigration that they are ‘extraordinarily talented". A group only needs to prove that it is "exceptionally talented". All need to prove that their talent has been sustained for an unspecified period of time, so the more print and online reviews and features you can produce to support your case, and the further back in time they stretch, the better your chances. And your chances will be further enhanced by letters of recommendation from prominent people in the music industry who can vouch for you, and your exceptional/extraordinary talent. Your visa agent will be able to advise you when your case is strong enough.

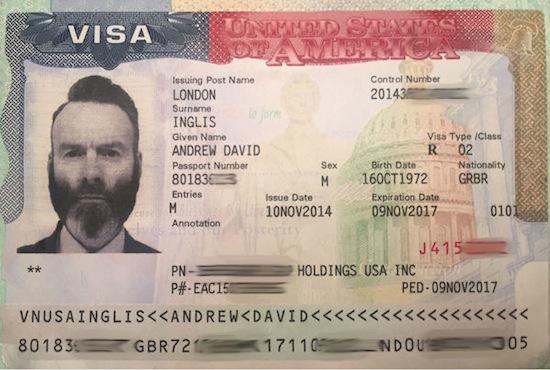

Here’s what I paid for our recent O1 and O2 Visas. The O1 is for the artist, the O2s are for the supporting crew:

$2,900.00 for the US side Includes Immigration Filing Fee, Union Advisory Fee and our Visa Agent’s fee

£538.80 for the UK side Includes Visa Processing Fee and Handling Charge That’s a bit on the high side, but I pay for peace of mind, and for a specific reason I’ll tell you about if youemail me

£2,538.30 total, for three people, or £846.10 each. Our Visas are for three years, which means it costs each of us £282.03 to work in the US each year.

That’s not expensive.

What is expensive, though, are flights.

I paid £2,405.85 for five flights for three people on one working trip, excluding excess baggage (London > US > London, plus two internals). £801.95 each. So it cost us almost three times the price of our Visas to get to the US to work in the first place, but I’m not sitting here wondering how I can lobby American Airlines for a reduction for artists and crew.

Now wait. That’s not a fair comparison; American Airlines are a commercial enterprise. They’re a company. They exist to make money. True, though once you see how much of the US Embassy in London is given over just to processing Visas, you’ll appreciate that the US Government isn’t doing this out of the goodness of their hearts either. Welcome to capitalism, the same capitalism we benefit from when we add a mark-up to our T-shirts at the merch stand. UK bands don’t have any inherent right to play in the US and the US Government isn’t obliged to make it easy for them to do so, any more than American Airlines are.

The arguments put forward by those angry at the perceived high costs, and what must appear to some like arbitrary application denials, seem to follow three paths:

It’s not fair because we’ve no idea why it was denied

It’s not fair because American bands can come to the UK for much less

It’s not fair because something something special relationship something"

Let’s take these in turn:

- Aye, fair enough. That must be hugely frustrating. Though if you haven’t done your homework/taken good advice/left enough time, when you had the chance to, then I’ve no sympathy

- The comparison between US and UK Visas is a bogus one. In every commercially relevant sense there is no comparison between the UK and the US. The UK population is 64 million, the US is five times bigger at 320 million. The UK has cities with populations of over on million people, whereas the US has ten. We have five indoor arena venues here in the UK, whereas the US has 87 – seventeen times as many. You’ll appreciate it’s not easy to count the number of small venues in both territories, so I’ve used indoor arenas for ease of comparison. The US has five times as many people, is forty times bigger in area, has five times as many large cities and seventeen times as many arena venues. In every measurable way the earning potential for a successful touring band in the US is far higher than in the UK. A better comparison would be to compare the cost of a US and a European visa, if such a thing existed. Though continental Europe is twice as populous as the US, it’s still a closer comparison to draw. The UK and US just aren’t analogous markets at all. And while I’m drawing comparisons, US bands (and those from Canada, Australia and other mostly white former colonies) generally don’t need work Visas to play in the UK. They only need Certificates Of Sponsorship which are entirely different things, and understandably priced very differently. I say "understandably" but a lot of people don’t seem to grasp it. It’s apples and oranges, but you go right ahead and call it apples and apples if it suits your rhetoric. And by the way, musicians from predominantly non-white countries most likely do need a visa to play in the UK… and a Certificate Of Sponsorship, all of which can cost them as much as UK bands pay for US visas, and which can be as arbitrarily denied.

- Winston Churchill has a lot to answer for. He first used the phrase "the special relationship" in 1944 and cemented its use in a speech in 1946. It’s worth noting he had an American mother. Seventy years on, the UK and US work together as it suits them, and how it suits them changes with the weather, and I swear to God the Obama administration has more to think about than whether or not your band’s going to get a knockback by Homeland Security at Austin–Bergstrom Airport in March this year. The Obama Administration doesn’t give a shit about your band, any more than the Tory government gives a shit about that US band you read about on Pitchfork last week. It’s safe to say that Churchill, Roosevelt and Truman didn’t give a shit either.

You do your argument a disservice when you use a seventy-year-old quote about an extraordinarily complex political relationship in the aftermath of a world war as a means to justify your annoyance that your desire to play music in America isn’t enthusiastically embraced by its lawmakers. You don’t get to go to America because you thought you were meant to be best pals. You get to go because you met the criteria for a successful visa application.

I’ve no reason to not salute those who’re fighting to have the costs reduced, but I wish they’d expend as much energy on pushing through the Agent Of Change principle, getting the music industry to financially support the small venues it benefits from, and speaking up about the sexism, and gender and racial inequality that surrounds them.

With thanks to Emily Moore for research and debate