Never trust an artist. Returning to his apartment, the young Soviet cinematographer Aleksandr Lemberg discovered his friend and colleague David Abelevich Kaufman had blackened the walls and ceiling in soot, upon which, he had drawn a multitude of clocks in chalk, all showing different times with wildly swinging pendulums. “I did not like this at all,” Lemberg later recalled. Kaufman was, by contrast, manic in his enthusiasm. In his mind, he had transformed what was merely a family home into a Russian Futurist masterpiece. The clocks were a visual poem levitating in the infinity of space-time. “A poem?” an incredulous Lemberg asked. “Yes! Listen… tick tock, tick tock…”

Few artists in any field have captured the dynamism and simultaneity of the city as Kaufman would as a filmmaker. You’ll recognise him by his nom de guerre (this was the time of early Bolshevism after all) – Dziga Vertov. He chose as his inspiration not the hard man ‘steel’ or ‘stone’ of his fellow revolutionaries but instead an identity based on the Ukrainian word for a child’s spinning top, accurately capturing his whirling energy and ideas. “Long live the poetry of the propelling and propelled machine, the poetry of levers, wheels, and steel wings, the iron screech of movements, the dazzling grimaces of red-hot jets” he announced in a manifesto in 1922. Somehow his work matched his fancy talk, especially in that inspiration/bane of every film studies pupil, Man With A Movie Camera, where the city is the main character (though the death-defying cameraman vies for the lead). Vertov was a prophet of a mechanised urbanised world to come, one that would sideline him and destroy countless others. As Soviet culture came increasingly under the Party and Stalin’s control, there was no place for such adventurists. Yet Vertov was no simple victim. He had not only been a propagandist for the regime but his ambitions for a Kino-Eye that would see everything had potentially monstrous applications. He was regarded in some quarters as an imbalanced vandal and an apologist of tyrants when it was modernity itself that was both dazzling and maniacal, facilitating and tyrannical.

Given recorded music has run parallel to the age of urbanisation, musicians have long attempted to convey the experience of cities in their compositions. The same year Man With A Movie Camera was being shot, George Gershwin was staging An American In Paris, incorporating Parisian taxi horns into the performance. Chicago blues, Blue Note jazz, Motown, krautrock, punk and post punk, metal, hip hop, and a multitude of different genres and movements across the world, were all in their different ways responses to the agony and the ecstasy of modern urban life. Electronic music exemplified this, being born in cities from Detroit to Düsseldorf, but also representing escape from metropolitan strictures, whether time (the rationalised miseries of the working week) or space (venturing into the countryside for raves or taking over derelict post-industrial haunts). This division – embodying city life and escaping from it – is Underworld’s realm.

The apotheosis was, of course, ‘Born Slippy .NUXX’. Its original frantic version sounded like a gem from an obscure rave tape. The remade cacophony, a B-side at first, made number two in the charts and consisted of shattered glass memories of falling through Soho, pissed-up imagism, a warning or a cry for help converted into a rhapsody for hedonism, set to a punishing four to the floor beat buoyed by cherubic synths. Trainspotting sent it into orbit but, while it’s hard to hear unburdened now, something electric is present in it from the start. Everyone cites the “lager lager lager lager” section but there’s a moment (“You got a velvet mouth / You’re so succulent and beautiful…”) when Karl Hyde’s cut-up loudspeaker sermon switches into a voice not unlike “the bird is the word”, as if pointing out the ‘look, no hands’ effortlessness of it all. It’s once in a generation beautiful. There’s a kind of post-Beat poetry to it in the way Howl or ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ or their acknowledged idol Gil Scott-Heron conveyed the sensory overload of city life, but this is beyond, propelled into the digital age with even less to cling onto. It’s not some static diorama portrait of a metropolis so much as a neural network; all movement, (lost) connections, joy and ruin inextricable. Every man and his dog these days is compared to Mark E. Smith but this is the way to do it – the Three Rs, the cut-ups, the evasion of singular meaning, the mix of the sacred (“You got to neverland on your telephone / And in walks an angel”) and the hilariously profane (“And look at me, your mum squatting pissed in a tube hole / At Tottenham Court Road”). With Underworld, there’s always a tacit rejection of the categorisation of electronic music, spurning the obnoxious elitism of ‘Intelligent Dance Music’ or any snobbery towards supposedly philistine doof doof music. Their approach was to use electronic music as a catalyst to make life cinematic, whether in a darkened bedroom or amongst the steam-rising hordes of a festival.

Most of the attention of Underworld’s reissued records will go on the triptych with Darren Emerson, their imperial phase, as the saying goes. I’ve written at length about Dubnobasswithmyheadman elsewhere on these pages, but listening back to the album alongside its successors, it feels like the opening credits of a film. ‘Dark & Long’ projects images of vast nightlands between cities being crossed at high speed, headlights on the road, constellations cartwheeling in the sky. Part of the incredibly compelling cinema of it is knowing but not knowing precisely that something, an entire life perhaps, has been left behind and another lies in the distance. And if it’s cinematic, the lyrics (“Me, I’m just a waitress” she said / “I went and bought a new head” she said”) are distilled David Lynch.

The city appears like a mirage with the shimmering beginning of ‘Mmm… Skyscraper I Love You’ and we’re soon submerged in bleeps and pulses, tumbling percussion, automated announcements, the lofty heights and the soiled depths (“Porn dogs sniffing the wind for something violent they could do” seen from a window of New York taxicab driving through Downtown Manhattan). ‘Dirty Epic’ is intimate and observational (“Ride the sainted rhythms on the midnight train to Romford… Here comes Christ on crutches”) with more than a hint of early Pet Shop Boys in its street-level voyeurism and kink allusions. By contrast, the truly epic ‘Cowgirl’ is a neon sign blazing high above the rooftops, promising ‘everything’ multiplied by infinity, but delivering nothing but dissolution (‘an eraser of love’). The exclusion of the sonic incarnation of coming up, ‘Rez’, still hurts after all these years.

Second Toughest In The Infants (named after a child relative’s boast) and Beaucoup Fish continue what is a remarkable plateau. Though the spirit remains the same, there are other influences now supplementing the musical palette. There’s an element of drum & bass to Second Toughest’s brilliant opening suites ‘Juanita: Kiteless: To Dream Of Love’ and ‘Banstyle / Sappys Curry’, as well as New Order-esque guitar stabs in the former and jazzy Warp-esque mischief in the latter. For a group renowned for pounding anthems (and ‘Pearl’s Girl’ is one, with its unlikely hook of ‘Rioja Rioja, Reverend Al Green’ salvaged from a drunken night in Hamburg), Underworld excel at shadowy chillout and lo fi moments like ‘Confusion the Waitress’ and the approximate-desert blues of ‘Blueski’.

The group may have worried about becoming too slick and proficient on Beaucoup Fish but there’s a seditious feel to the anthems of the first side, with ‘Push Upstairs’ and ‘King of Snake’ applying a white-hot blast furnace treatment to piano-led dance music. In lesser hands, ‘Cups’ would be lethargic lounge, but Underworld create a distorted space age environment to sink into. ‘Jumbo’ may be the most quietly influential of all their tracks – you can hear its wonkiness and its soar in Hot Chip, Caribou, Floating Points, and a host of others – while the thrilling ‘Moaner’ ends the trilogy on a high, with Hyde sounding like a techno Nick Cave at his most biblical (“Black metal walls are crawling / I am the hunger above your town”).

Despite Emerson’s departure, there was little sign of Underworld losing momentum, or reverting to the electro-pop of their origins, with A Hundred Days Off. The duo come out swinging and the collection holds its own with the trilogy it followed. ‘Mo Move’ is a gorgeous mix of cloudy psychedelic vocals and Vertov-clinging-to-the-front-of-a-train beat; a neuro-kino landscape flickering past. ‘Two Months Off’, with its wedding bell cascades, is out-of-body ego-death anthemic. Every Underworld album has two or three such nuclei, bangers in contemporary parlance, and smaller electrons spinning around them. The album’s relative eclecticism may have been seized on by naysayers – the dervish whirls of ‘Dinosaur Adventure 3D’, the country blues licks of ‘Trim’, the 5am at the sesh spirit channelling of ‘Little Speaker’ – but there were always trace elements of Americana etc in Underworld’s music.

By the time of Oblivion With Bells, the prevailing critical view was that the band’s powers were waning. Listening now, this feels entirely misplaced. The cyberpunk ‘Beautiful Burnout’, for one, is glorious. ‘Boy, Boy, Boy’ is a moving riposte to ‘Born Slippy .NUXX’, both circling around addiction (“All your Sundays come back to haunt me / I like to hurt myself like this sometimes”). ‘Ring Road’ has the feel of fellow Essex Boys Depeche Mode, or Nine Inch Nails if Reznor wrote songs about wheelie bins and abandoned shopping trolleys. What seems to have happened was a case of fatigue on the listener’s part rather than Underworld. Familiarity breeds contempt and Underworld had, by then, been so consistently excellent that it was easy to take them for granted, even discard them. ‘Crocodile’, for instance, has so many of the trademark parts of a brilliant Underworld tune that it could seem that we’d heard it many times before. They were victims of their own consistency and our gluttony for novelty. It’s not them, it’s us etc. A hundred flights and the passenger begins to long for turbulence, a thunderstorm, an aileron roll. It’s an album that deserves revisiting and now is the time. Oblivion With Bells emerged following a tide of material created during Underworld’s ambitious Riverrun project, where they explored different ways of recording and interacting with their audience, both straight and oblique. No doubt this was an invigorating but also an exhausting process. The problem might be that, as with its Finnegans Wake-derived title, for all the venturing you find yourself meeting yourself back where you started.

Their only creative misstep in the series occurred with Barking. Yet even this was only partial. Often the most interesting points in artists’ careers are before they find their creative voice and after they lose it, the strange paths not taken, the reinvention aberrations. It was clear from its Kandinsky-esque cover that the duo were seeking new colours. And by working with different electronic artists and producers, they gave it a fair shot. Yet it feels like a retreat after the expansive deconstruction of I’m A Big Sister, And I’m A Girl, And I’m a Princess, And This Is My Horse from Riverrun, which was courageously experimental and full of possibilities. Barking starts well with the brooding Dubfire (Deep Dish) collaboration ‘Bird 1’. ‘Always Loved a Film’ has a satisfying thwack and build to it but is let down by a ruined orgasm of a climax, and a distracting similarity to Sammy Davis Jr.’s version of the ‘Rhythm Of Life’. Too often, the tracks start adventurously but end up disturbingly normie (the aforementioned track), directionless noodling (‘Hamburg Hotel’) or stuck in treadmill circularity (‘Scribble’). Nothing is disgraceful though. The Paul Van Dyke collab ‘Diamond Jigsaw’ is almost the anthem it reaches for and there is joy when it suddenly erupts. ‘Moon In Water’ is class throughout, sounding futuristic and deeply 1980s simultaneously. It’s like finding a breeze while lost deep in a cavern. The finest moments are those of imitation rather than innovation such as the chiming New Order-style guitar towards the end of ‘Grace’. The external production has, however, a taming impact on their sound and you long to either hear the original material stripped down or what a genuinely twisted series of producers could have done with it. Instead, the results are pedestrian for a band that are usually time-lapse accelerationists, safe for a duo skilled at menace and debauchery. Good, even great, by anyone else’s standards but not befitting their heights. The songs are arguably there. You can hear Underworld in there, acting like their usual selves but something’s not quite right, not quite Underworld. It’s like the music is blinking in morse code for rescue behind a rictus smile.

There was a sense of relief and triumph then to Barbara Barbara, We Face A Shining Future. Named after a line Rick Smith’s father said to his mother at the end of his life, it has been framed as a comeback from some kind of fallow period. Given this time included soundtracking the Olympics, movies, an excellent Hyde solo album Edgeland and two full-length collaborations with Brian Eno, how many musicians would flog an organ to have such a career low? Much as Underworld’s lows are overstated, so too is this resurrection. It’s unquestionably an exceptional album and one that feels increasingly exotic. The opener ‘I Exhale’ is monumental, the vocals are a Mount Sinai Mark E. Smith. The urbanist danger and euphoria are there (“Asbestos roofs / Corrugated rhythms”) as is their healthy self-deprecating absurdism (“Big blue / Blah blah blah blah…”), while the atmospheric finger-picking of ‘Santiago Cuarto’ and the blissful nazar of ‘Motorhome’ border on psychedelia and couldn’t be more different from the plentiful house and techno sky-punchers. Underworld found their new colours out in the wide world.

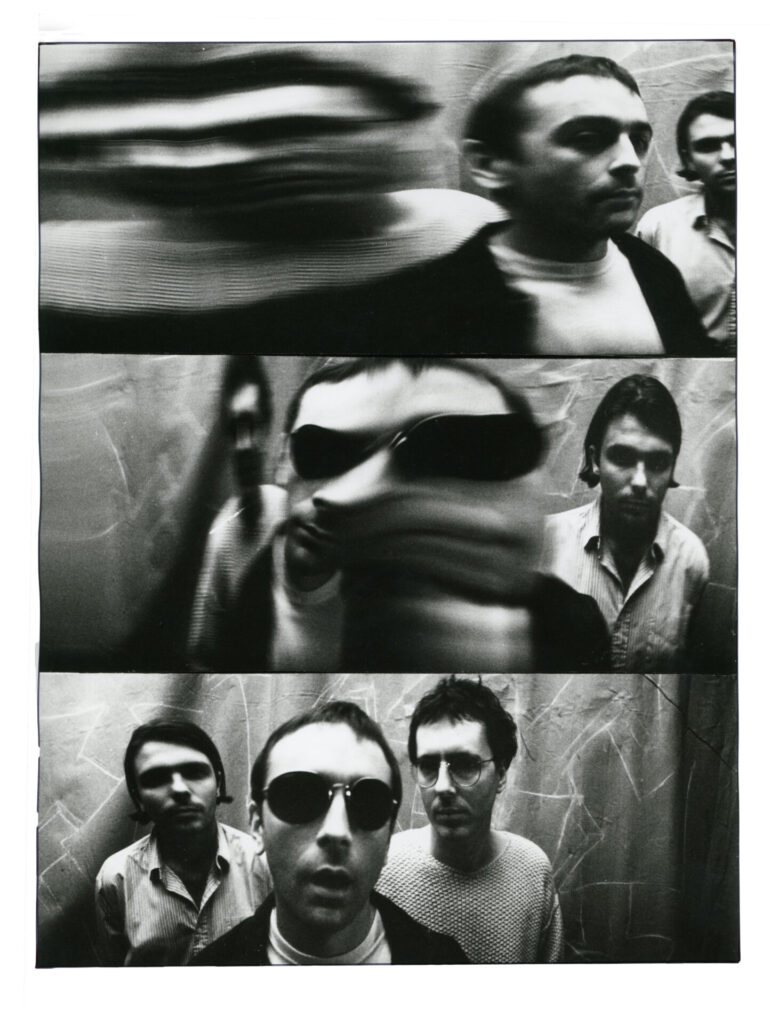

The reissues have not extended yet to more recent fare. Their Drift series, for instance, is their most explicit embracing of psychogeography/situationism and the album Drift Series 1 remains, for what it’s worth, this writer’s favourite Underworld record. It directly addressed the great theme that runs through all their work – the city and the individual. It’s obvious from the earliest cryptic cover art of the reissues, the xeroxed collages that reflect the palimpsest of urban life, influenced by everything from Dada to Lettrism, Jacques Villeglé’s torn posters to Bob Cobbing’s typewritten concrete poetry. Yet it goes way beyond aesthetics. It is not art that is fracturing in the urban/digital age but us, our psyches, communities, and souls. In The Metropolis And Mental Life, Georg Simmel wrote, “The deepest problems of modern life flow from the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society, against the weight of the historical heritage and the external culture and technique of life.” The challenge remains, far more now than then, how to exist in any meaningful authentic sovereign way when bombarded and compromised from every direction? The genius of Underworld is to encapsulate this sensory overload and, unlike Vertov who for all his stunt-filmmakers was all for the city overwhelming the individual, advocate for the interior soul and its flight. Trance might even be a form of resistance now to the constant bombardment of data that’s clearly fucking us up. Underworld may have sounded the way Vertov looks; Man With A Movie Camera with a drum machine and synths. Yet they were and remain on the side of the beleaguered half-mad citizen, finding a crooked path through an ever-changing labyrinth to some kind of transcendence, escaping the void and the clock. It turns out that redemption is other people, through desire, love, and exiting solipsism. Listen back and hear how many boys and girls are in those Underworld songs, how many attempts to reach out, in defiance of atomisation, to another for some kind of communion that would prove each other to be real in a world of illusion. They were love songs all along. Bringing darkness into the cities. Bringing light into a dark place.

New reissues of Underworld’s album catalogue from 1994 to 2016 are available now via Smith Hyde Productions