On a quiet night in a few years ago, I found myself on YouTube once again watching clips of Threads, the 1984 nuclear war film made by Mick Jackson and Barry Hines, and it struck me that I found the experience weirdly comforting.

The realisation made me feel sick. After all, what kind of person would find one of the bleakest, unsparing films ever made reassuring? First broadcast forty years ago this weekend, Threads is a speculative television drama which portrays the run up to and the aftermath of a nuclear missile exploding over a British city. The backdrop is one of creeping international tensions as the lives of two families, the working-class Kemps and the middle-class Becketts, are brought together by an unexpected pregnancy. News headlines, radio bulletins and TV reports are ignored right up until the point this becomes impossible. In the background to the quotidian drama the viewer can see things unfolding nightmarishly on news reports as the Soviet Union invades Northern Iran then moves nuclear warheads to Mashhad; the US deploys B-52s to Turkey, then one of its submarines is sunk in the Persian Gulf.

Forty-seven minutes in, a nuclear bomb detonates above the North Sea, followed by a second wave focused on NATO military targets, then a third at economic and industrial centres, including Sheffield. The next hour and ten minutes show the full bleakness of what could happen to humanity after such an assault: slow deaths, harrowing grief, the collapse of civil order, the onset of a sickening nuclear winter. I kept going back to this stuff – I’m still going back to it now – seeking solace in the detail. But I found out it wasn’t just me. There are lots of us out there.

While making a documentary for BBC Radio 4, Reweaving Threads: 40 Years On, which is being broadcast this Saturday, I realised that I’ve become embedded in a community of ‘Thread-heads’. I scoured IMDb messageboard posts dedicated to the film after Threads director Mick Jackson told me about the film’s presence on the site. He’s still a regular lurker himself. Why? “To see if it’s still reaching people”, he explained.

Notable ‘Thread-heads’ include author Julie McDowall, the creator of the Atomic Hobo podcast, which analyses Threads in four-minute-chunks over the space of 29 episodes, and filmmakers Rob Nevitt and Craig Ian Mann, who’ve spent the summer interviewing extras for a documentary to accompany Severin Films’ 4k UHD release of Threads, due in January 2025. (“We’ve spent the last few months making old ladies cry,” was Mann’s response when I asked him how he’d sum up the project.) Threads also featured recently in Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard’s Horror Show, at London’s Somerset House; and hangs as a heavy presence in the worlds of Scarfolk, The Haunted Generation and Black Mirror. The creator of the latter, Charlie Brooker, talked about how the film cast a long shadow over his television work while a guest on Desert Island Discs in 2018. It is a huge influence on filmmaker Martin Stirling, especially this startling 90-minute film for Save The Children in 2018, and was even re-shot scene for scene during the same year by director Richard DeDomenici in the original locations, as Threads Redux. (If you squint hard enough while watching this update you’ll be able to spot me, as an extra, running around Sheffield shopping district The Moor when warning sirens go off.)

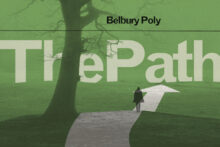

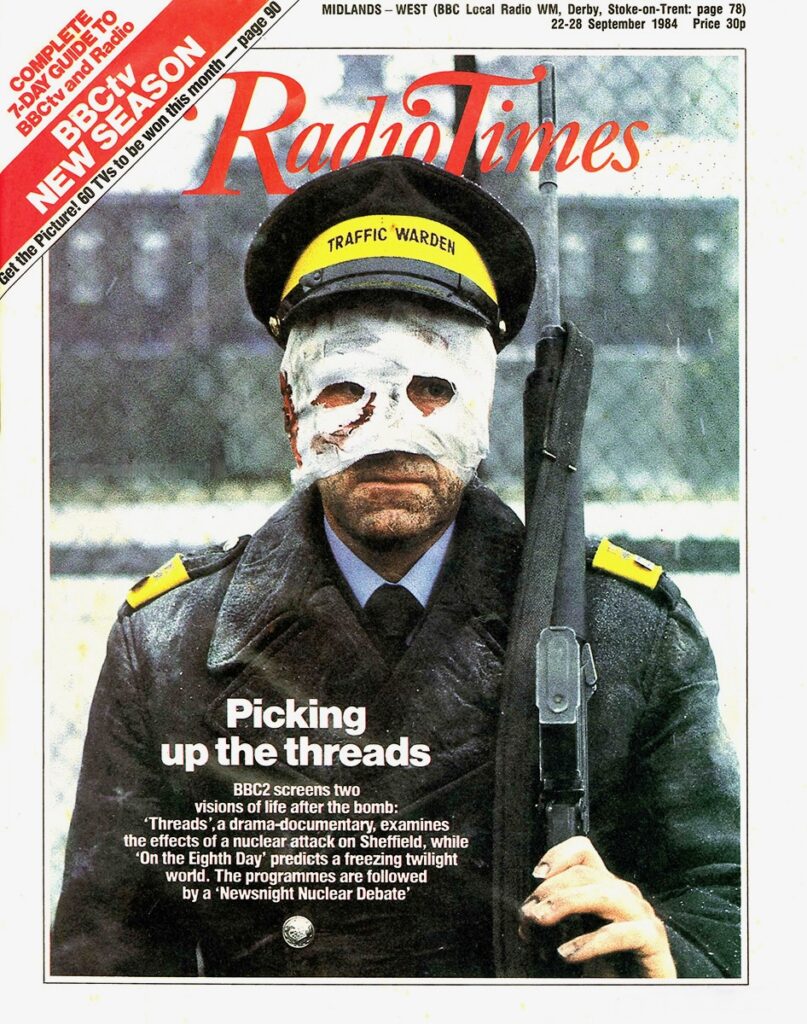

Many screenings are happening this month, one staged in a nuclear bunker, another followed by a walking tour of Cold War locations, several featuring specially pre-recorded Q&As. A sold-out screening at the Sheffield Film Festival this summer even featured a Q&A with its most famous extra: Michael Beecroft, a traffic warden who moonlighted as an extra on local productions, and spent just one day on the shoot, having been told to come along wearing his uniform.

The actor ended up on the cover of the Radio Times on the week of Threads’ broadcast, his head wrapped in bloodied bandages, a gun over his shoulder. He was found earlier this year by BBC Sheffield after a tweet by Craig Ian Mann which got over 200,000 views. Was this level of engagement because people wanted to know if there was someone real, someone human, behind what that image represented? Either way it was an act of macabre sublimation of the everyday into a generation-defining image of horror.

The chief ‘Thread-head’ is arguably Sean Judge, founder of the Threads Survivors website, who creates action figures of the traffic warden. An anatomical pathology technician by day, a pop culture obsessive by night, Judge is one “of those people who have shelves of stuff about nuclear war… a Geiger counter, fallout signs”. Self-deprecating black humour is never far away when he talks to you.

Judge first saw Threads in the aftermath of 9/11 after reading a post about the “top ten most disturbing films” on IMDb. He hunted down a VHS copy at Maidstone’s Tower Records for £17.99 (“and bought it alongside a copy of This Is Spinal Tap, which gave me some relief”). He now owns two VHS copies, two DVD copies and two Blu-Ray editions of the film and is, no doubt, looking forward to owning the 4K. On first viewing, he found Threads “very traumatic”, but also felt the intention of the film makers had come from a “good human place”, a perception that has only strengthened in the years since. He set up the Facebook group in 2018 as a “safe space” place to discuss it. Why? “Because most people don’t want to chat about something like this, but some really do.”

We discuss the idea that neurodivergence may be one of the linking factors between some ‘Thread-heads’; certainly some research has shown that ADHD can cause the mind to loop around distressing subjects, and elsewhere that so-called ‘existential OCD‘ often involves persistent and intrusive rumination on the meaning of life and existence. By the same token however, it’s true that Threads can dredge up murky childhood memories of ‘nuclear war’, sensations that viewers actively want to revisit or re-experience. Judge says a viewing can be a chance to trigger other less obvious, more complex feelings “that they want to work out”. Two nuclear physicists, a former USAF ICBM operative, or “missiler”, and several other ex-military personnel are among their number, as are people who haven’t even braved watching Threads yet. Judge thinks he knows what bonds them all: “Finding other people who have the same thoughts about something very heavy.”

The group’s membership is now at 1,300, having increased by 30% since the summer – “and it’s busy all the time”. Judge’s action figures are in demand. He hand-paints them unless the recipients fancy painting them themselves. He’s also done stand-up in the past and is writing a one-man play on the subject.

I commissioned Jim Jupp of the Ghost Box label and Belbury Poly to create an original soundtrack for the Radio 4 documentary. He used synthesisers commercially available in 1984 as a starting point, even though usually when he makes music, he is concerned with fighting against nostalgia: “I want to connect with the energy of my youth differently, to reframe stuff from my past in a more fantastic way.” His work on the documentary supports the sound design of my producer Leonie Thomas, who used audio archive from the film itself, and many of the programmes made in response to it, as well as new interviews and my script. This audio response to the film – an act of creating new art from the rubble of the past – strikes me as something both productive and healthy.

I had a lightning-bolt realisation about my Threads obsession while making the documentary. I lost my dad suddenly in 1984, as I’ve written about before, a trauma that I kept buried under my day-to-day life. As a child I became fixated by other disasters I was exposed to via TV, revisiting them time and again as an adult. I’ve watched countless documentaries about the horrors of the 80s: about the IRA, Lockerbie, Hillsborough, Zeebrugge and the distressing fate of the Challenger shuttle, moments of horror and trauma from a frightening decade that other people experienced from the same perspective as me, hearts racing in their chests, while sitting on their sofas. These disasters existed outside my younger, grieving life, outside of the specific situation about which I felt couldn’t talk to anyone. World events held horrors that everyone understood, and felt like better places to put all these feelings – I felt comfort in being able to think about horrifying things in similar ways to other people. Watching Threads as an adult also reconnected me to the textures of my 1980s… the fashions, the haircuts, the contexts of my earlier grief. From a safe distance, I could make my traumatic past come alive, in a way I could control.

Threads also reminds me of how it felt to live on British soil in the 1980s. It was screened during the miners’ strike and two weeks before the Brighton bomb. It features a CND protest in which a woman on a megaphone says industry will be destroyed by a nuclear attack, to which a man responds, angrily, “We’ve got no industry in Sheffield!” Jimmy’s father reacts to the news of Ruth’s pregnancy by saying “Hell of a time to be starting a family in the middle of a recession.” He does this while serving tea in his apron, a detail that the Barry Hines-studying academic David Forrest believes was not a sign of gender equality, but of job loss.

Threads takes me back to the South Wales where my father died, where my grandfather had ‘been retired’ early due to the savage “slimlining” of the steel industry, to a house where the TV was always on, relaying the news. The presence of current affairs media as a colouring agent in the drama has a chilling quality, calling to mind Jean Baudrillard writing in America: “There is nothing more mysterious than a TV set left on in an empty room… it is as if another planet is communicating with you… a video of another world, ultimately addressed to no one at all, delivering its own message.” The television set talks to itself until you have to listen.

Other ‘Thread-heads’ have recognised themselves in my theory about my response to the film, their childhoods or young adulthoods involving comparable tough times. That said, every life involves grief and darkness, of course, and we’re not the only people spending downtime drawn to other grim subjects. A 2023 interview I did with film professor Tanya Horeck for The Bunker podcast, about the pull of the profitable genre of true crime, became instructive in the context of Threads. Watching heavy things, she said, can “make you feel safer in your own life”, and watching Threads, for me, does to a point.

“A reassuring narrative frame” helps, though, she added – which is something that Threads doesn’t have. After the bomb, several of its main characters just disappear. The film literally stops mid-silent scream. Its storytelling isn’t formulaic, but jagged, without easy resolutions, abrupt. A lot more like life.

In his recent book, Everything Must Go, an extensive survey of apocalyptic narratives in pop culture, Dorian Lynskey explores how end-of-the-world stories have persisted across decades, centuries, and millennia even; but agrees that the shadow of a mushroom cloud gives these specific tales an explosive urgency. Susan Sontag’s 1965 essay on atomic-era films, ‘The Imagination Of Disaster’, is a key text quoted by Lynskey: “One can participate in the fantasy of living through one’s own death and more, the death of cities and the destruction of humanity itself.”

“The idea that people quickly clung to [in the face of a nuclear attack] was that the lucky people in that horror are the ones that die,” Lynskey says. A quick ending is so much easier than prolonged deterioration. His main motivation for writing his book was to find out why people were attracted to such narratives, he added. Did he get a clear answer? “People are drawn to exploring their fears through telling stories about the worst thing that could happen.”

Sometimes people are also driven by the idea of starting again from scratch – Lynskey mentions HG Wells visiting San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake when 80% of the city was destroyed, noticing how positive people were about building something new. Threads doesn’t allow those who live in its world this potential, as the research Mick Jackson was digging into during 1983 didn’t allow for happy endings – the conferences he attended, the books and papers he read suggested a much gloomier prognosis. These findings were delivered to us, in clipped BBC received pronunciation, by Threads‘ narrator and BBC Horizon presenter Paul Vaughan – but the actual characters in the film felt real, even though they were fictitious. Now when we watch them, we are watching them from the future, from afar, from a vantage point that allows us to pay attention, and to take action.

While researching I interviewed Dr Sylvan Baker, who wrote about the power of docudramas for academic website, The Conversation. His experiences in care as a child have fed into his profession as an adult, working in what he describes as “verbatim theatre… using the words of real people to tell stories that explore a range of social and political issues, and offer a voice to unheard perspectives”. He judged the use of relatable language and dialogue in Threads essential to the powerful psychological effects it created: “Threads offers an invitation to change the relationship to the piece of testimony, narrative or information that you’re being exposed to.”

“The drama is a bit of a MacGuffin to allow you to be exposed to the enormity of what happens if a nuclear device explodes. People are watching a version of themselves on screen, and this might sound flowery, but they’re watching a version of themselves dead or dying.” When I watch Threads, I think of my hometown, Swansea, similarly full of post-war concrete, milk vans shuddering around terraced streets, old blokes in anoraks drinking in Victorian pubs. Everyday objects in Threads also linger long in my mind: Jimmy’s bird book – a nice nod to Barry Hines’ past as the author of Kes – which Ruth carries around like a totem; Michael’s early handheld electronic game, which his father cradles in the absence of his youngest child who is now dead; the milk bottles melting on the step, an incredible call back to Alison Kemp sipping on a drink just weeks earlier while studying French homework, pausing a Walkman in order to listen to a TV news bulletin. I always think of my teenage self when I think of her, mainlining music, working hard to aim for new horizons, not knowing what is coming next.

The depth of Threads is fractal; there are so many other things I could share with you given more time and space. You could read Russell Hoban‘s review of the film published in The Listener and consider how his incredible novel, Riddley Walker, might have influenced the breakdown of language in Threads. I want you to notice that the milk van that pulls up on the morning of the bomb has Hillsborough, Leppings Lane, on its destination board, a visceral reminder of another horror yet to unfold. I want to tell you how Mick Jackson’s wife was in the early stages of pregnancy when Threads was being filmed, and due the day after the broadcast – he wore a beeper while appearing on Pebble Mill At One in case she went into labour. His daughter is forty in a few weeks time, and she has decided not to have children, he told me, because of the state of the world. I think of Ruth giving birth to her child in a barn during a freezing December, her fiancé, a carpenter, having vanished. A strange, twisted nativity.

I also want you to know about Jan Nethercot, Threads’ head of makeup, now a potter in her 70s, who showed me her astonishing archive of the production, hidden away in a cupboard for decades. Polaroids of every person she made up, plans showing the degradation of their bodies, and even a drawing that actor Karen Meagher (Ruth) made of her at sitting at her kitchen table surrounded by vats of boiling fake blood.

I’ve since put Jan in touch with Dave Forrest at the Barry Hines archives. The day I’m filing this piece, Sean Judge published a letter on Threads Survivors which he wrote to Mick Jackson accompanying a traffic warden doll, now on its way to America’s west coast. I’ve told you about groups, films and books that have helped me work through my fears, and this in turn helps me to communicate with you, to know that this ‘Thread-head’ is not alone. The act of creativity has been the precursor to making genuinely meaningful connections that lift me out of the dust of my past. Telling stories in new ways, it turns out, also helps some of us understand who we are.

Reweaving Threads, 40 Years On, is on Radio 4 on Saturday 21 September at 8pm