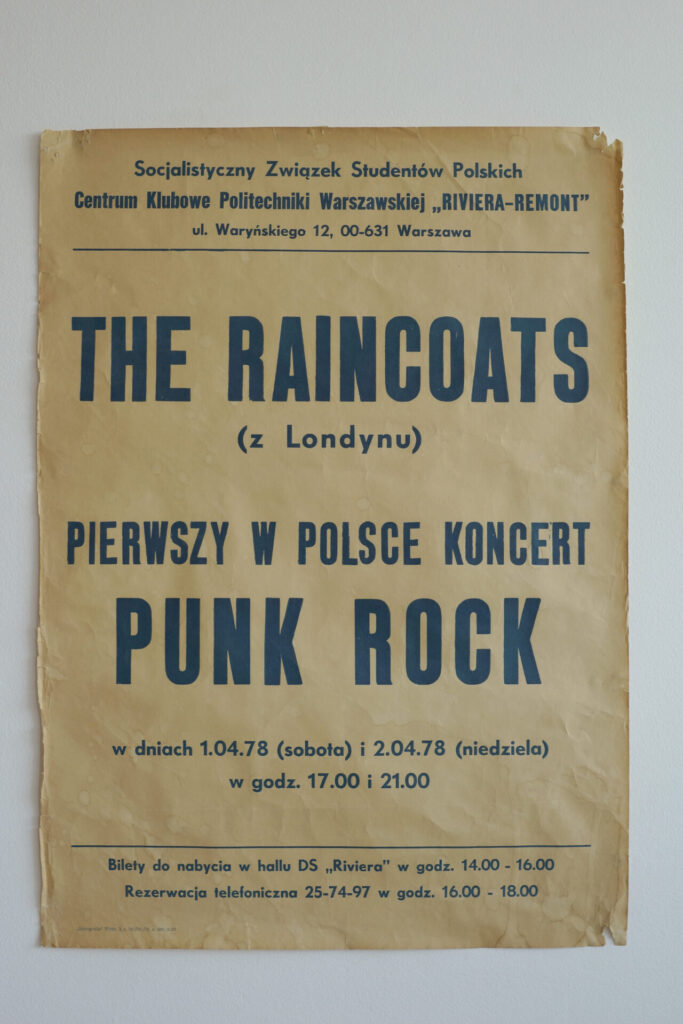

In March 1978, The Raincoats boarded an eastbound night train from London. They were headed behind the Iron Curtain, where they’d be the first punk band to play in Warsaw. Students and activists who’d soon take on significant roles in the country’s burgeoning Solidarity movement had organised underground gigs, and The Raincoats got invited to play. At Friedrichstrasse station in East Berlin, guards appeared, pointing machine guns, tightly gripping the leashes of their Alsatian dogs. From the elevated station, the band could see the Berlin Wall behind them and the old-fashioned East German cars directly below. “It was almost like a black-and-white spy film,” co-founder Ana da Silva recalls. “The lights were all dim. But of course maybe your imagination starts to run away when you’re in East Berlin.”

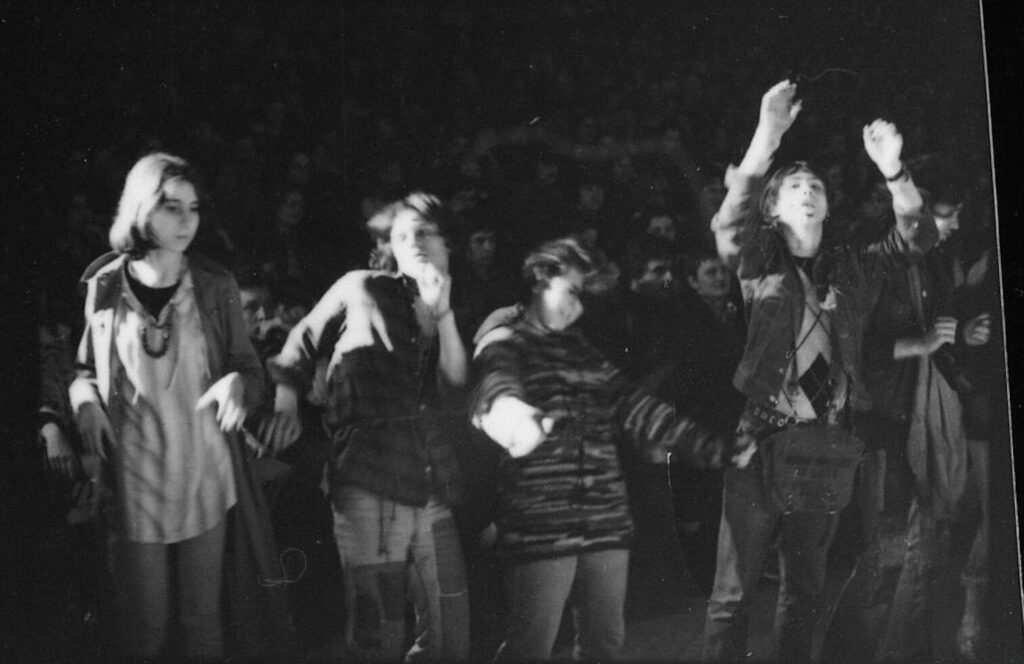

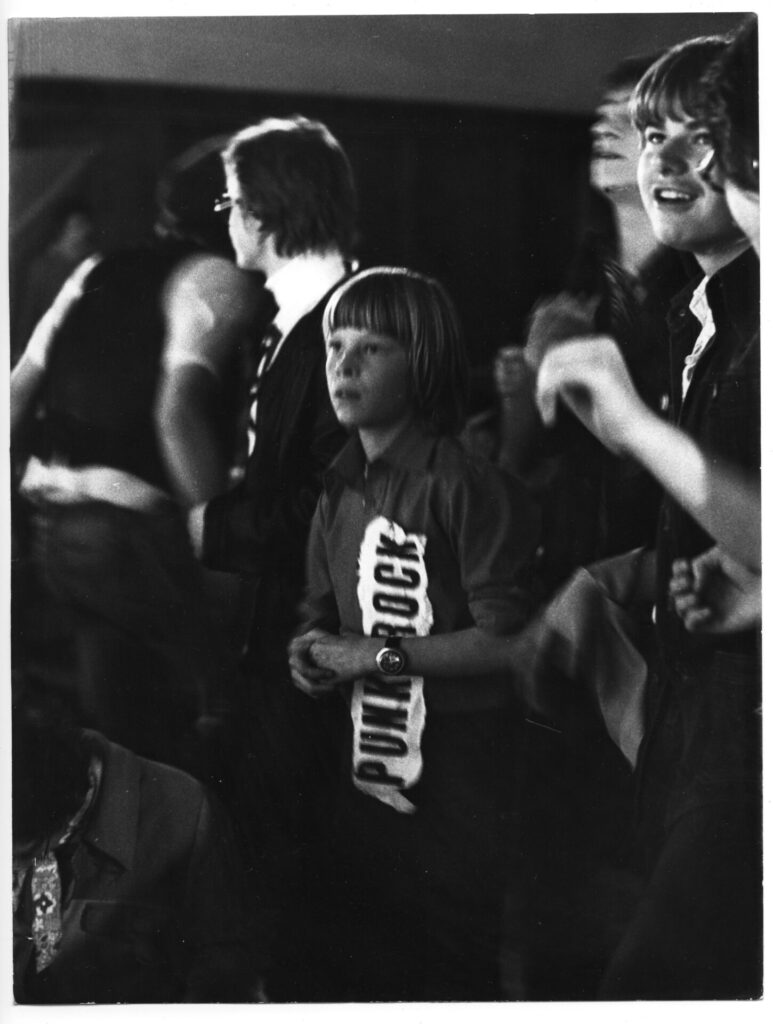

By morning, their train stopped in Warsaw. Tomek Lipinski, a young Polish activist, met them at the station. Ana initially wondered if Tomek had been sent by the communist government to spy on The Raincoats, and she felt uneasy. As it turned out, Tomek was part of the resistance. For him, from the moment he greeted The Raincoats on that train platform, the possibility of revolution permeated the oppressive Cold War air. The Raincoats would perform twice over two back-to-back nights — to hundreds of student punks and political activists in the making who’d turn that music into a powerful weapon against authoritarianism.

Across geographic spaces and moments of political oppression, music has been used as an armament to defy tyranny – a hammer breaking down walls, a dagger aimed at the heart of racist and gender-based violence, and a flame illuminating passageways through darkness.

In the Warsaw ghetto of the early 1940s, just a short walk from where The Raincoats would play to crowds of young rebels three decades later, music could be heard – it became a way of expressing Jewish identity as Nazi occupation sought to extinguish it. Across the Atlantic, Billie Holiday recorded the haunting jazz standard ‘Strange Fruit’, a cry-out against racist murders in the American South during the final, often brutal phase of racial segregation. Young political prisoners detained in the 1950s and 1960s by the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal taught themselves “protest music serenades” to survive being tortured in the dictator’s prisons. As Ana and fellow Raincoats co-founder Gina Birch were thinking about starting their band in mid-1970s London, Jamaican musicians such as Bob Marley battled racism through their recorded output, placing the idea of neocolonial oppression firmly in the consciousness of the young. And Rock Against Racism soon entered full-swing in the UK, pushing back against the white nationalist politics of the far right National Front party.

The political power of music has been wielded at specific moments of tyranny throughout the last century. The Raincoats’ music has made a particularly distinct sonic armament, its message moulded by young activists in different places and times to be deployed against numerous injustices.

Against political oppression in Lisbon, Portugal to Warsaw, Poland; against gender-based violence in London, England and Belfast, Northern Ireland to Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina; against anti-LGBTQ laws in North America and the UK; and against the re-emerging right-wing regimes that continue to threaten equality and freedom in the twenty-first century — The Raincoats’ music has served as ammunition for resistance.

The start of The Raincoats’ resistance timeline begins in Portugal with Ana. There, she witnessed her mother’s inability to participate in Portuguese social and cultural life under the Salazar dictatorship, rooted as it was in misogyny and patriarchal religion, and her cousin’s arrest for his role in the resistance. Ana started to find her voice by attending university protest meetings and listening to clandestine music. The songs of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell were among the first to teach her “alternative ways of thinking, being, and living in a freer way.” In that Civil Rights-era music, Ana learned that one could “use music as a weapon.” She’d soon find a co-conspirator in Gina, a rebellious art student who’d become part of London’s squatting revolution.

Ana and Gina initially created sonic weaponry during their foray into the Eastern Bloc (just four months after playing their first-ever gig in London). They didn’t realise it at the time, but they’d change the lives of some young Poles who sought political freedom. Tomek was the band’s guide in Poland and shortly after The Raincoats played their Warsaw gigs, Tomek started one of the first Polish punk bands, Tilt, and performed on underground stages. “They didn’t want that music to spread in Poland,” Tomek says today, describing a government that sought to maintain control over its citizens by criminalising any kind of radical idealism. Tomek wasn’t deterred; he knew what music could do after seeing The Raincoats. He got a Dutch filmmaker to sneak a Fender Telecaster into Warsaw for him (“there were no guitar shops here,” he explains). With his guitar in hand, he listened to The Raincoats and other punk tapes he kept on the sly, and wrote resistance music. When martial law was imposed in 1981, he was beaten severely by authorities along with fellow activists but refused to stop copying cassettes, making music, and spreading the good punk word. In 1989, the government fell, and he forged a thriving career as a musician in one of Poland’s most popular rock bands of all time, Brygada Kryzys. “The Raincoats completely changed my life, my reality,” says Tomek.

At that exact moment far west of Warsaw, The Raincoats’ music was being taken up as a weapon in a far different set of political circumstances, the sectarian violence of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Young people around the same age as the Warsaw giggoers were being inculcated by the narrow ideological borders of their worlds, committing acts of violence in the names of republicanism and loyalism. In the political prisons that housed the hundreds convicted of crimes against the state, Long Kesh (or “the Maze”) and Armagh Gaol, The Raincoats’ music shot through the walls and communities that surrounded them. That story begins with activist circles across the Irish Sea in London.

Vicky Aspinall, Raincoats’ violinist and ardent feminist, roomed with likeminded Caroline Scott, an accountant by day and political activist by night. Vicky and Caroline attended Troops Out Movement meetings (supporting Irish republican and anti-colonial politics), shared a flat, and together wrote ‘Off Duty Trip’. Those lyrics targeted rape as a weapon of war, condemning the news of a British soldier acquitted for a heinous act of sexual violence. It was among the first songs in history to so directly address rape in this context, and its impact reverberated across the Irish Sea; nonpartisan rape crisis centres began emerging, The Raincoats played benefit gigs in support, and likeminded artists began to speak out. Leeds-based post-punk band the Au Pairs released the politically-related song ‘Armagh’ on their 1981 debut album Playing With A Different Sex.

In that year’s June issue of second-wave British feminist magazine Spare Rib, editor Lucy Whitman heavily quoted ‘Off Duty Trip’ in a feature on institutional power and male violence. With new consciousness, she suggested, women were turning their political anger into sonic power.

Around the same time the Au Pairs heard ‘Off Duty Trip’, Rough Trade received a piece of Raincoats fan mail with a startling return address: H.M.P. Maze, Belfast. Political prisoner Jim Kyle, just a teenager, had received copies of Raincoats records thanks to Sue Donne, who handled Rough Trade mail orders.

Now, you might assume feminist punk fans in the Maze were members of the IRA, of the same republican cause Vicky and Caroline supported. Jim was a loyalist. Yet he and other young loyalist prisoners were also coming of age amidst the rise of punk. Jim’s cellmate and longtime friend, William Mitchell, learned about protest music from Jim, and the two began to see themselves as part of a burgeoning sonic cultural revolution. In his fan letter, Jim made clear there were no sides to take as far as sexual violence was concerned; he voiced his frustration toward “that bigot [Dave] McCullough” who’d written a sexist review of The Raincoats’ self-titled LP. “The standout for me,” he concluded in his letter, “is the excellent ‘Off Duty Trip’.” Access to Raincoats records in the Northern Ireland prison made possible a music education that opened minds amidst stifling ideological walls that led Jim and other young people to commit acts of violence. Upon release from the Maze, Jim opened a record store and William founded a reconciliation initiative in Belfast; they came a great distance, due in part to music like that recorded by The Raincoats.

Two decades later, The Raincoats would again offer a sonic sabre against gender-based violence. War raged in the former Yugoslavia, and Serbs attempted a genocide against Bosnian Muslims – murdering men and boys, and establishing “rape camps” (a measure intended to prevent the births of Bosnian Muslims, as Islam is patrilineal). Nirvana’s record label, Geffen, decided to release a Bosnian Women’s Aid charity CD in the mid-1990s. The label had already reissued The Raincoats’ first three albums on CD in the US and asked the band to be part of the CD compilation. Once again, their music became part of a sonic arsenal carried to the front in the battle against gender-based violence.

The Raincoats’ sonic weaponry was often distinct in its subtlety, underscoring that resistance music takes many forms. In 1983, for example, while reggae artist Peter Tosh unveiled an M-16 guitar on stage in Los Angeles on his Mother Africa tour, rallying support for South African boycotts that would eventually bring down the end of the racist Apartheid regime, The Raincoats’ music was being reshaped on the sly by LGBTQ activists in Toronto, Canada.

G.B. Jones, who co-founded the band Fifth Column and zine J.D.s, was mining lyrics for queer allusions and found kinship in The Raincoats’ music. In J.D.s – the zine that would open the idea of “homocore” to the world and in which G.B. would coin the term “queercore” – G.B. made sure other queer punks tuned into The Raincoats’ song ‘Only Loved At Night’; it appeared repeatedly on the zine’s Homocore Top Ten list. It “was even more overt than other songs we included on that chart,” G.B. says while referencing the song’s “whole section devoted to the female protagonist and her relationship with another woman.” Through music and kinship, G.B. helped give rise to a queecore community with grassroots strength, and songs like ‘Only Loved At Night’ became part of their arsenal. They formed their own bands, joined other activists in protest, and fought for LGBTQ rights. Following the passage of homophobic Section 28 in the UK, filmmaker Lucy Thane recalls being gifted a Raincoats cassette. With that armour, she became part of London’s “queercore militia” that protested across the city.

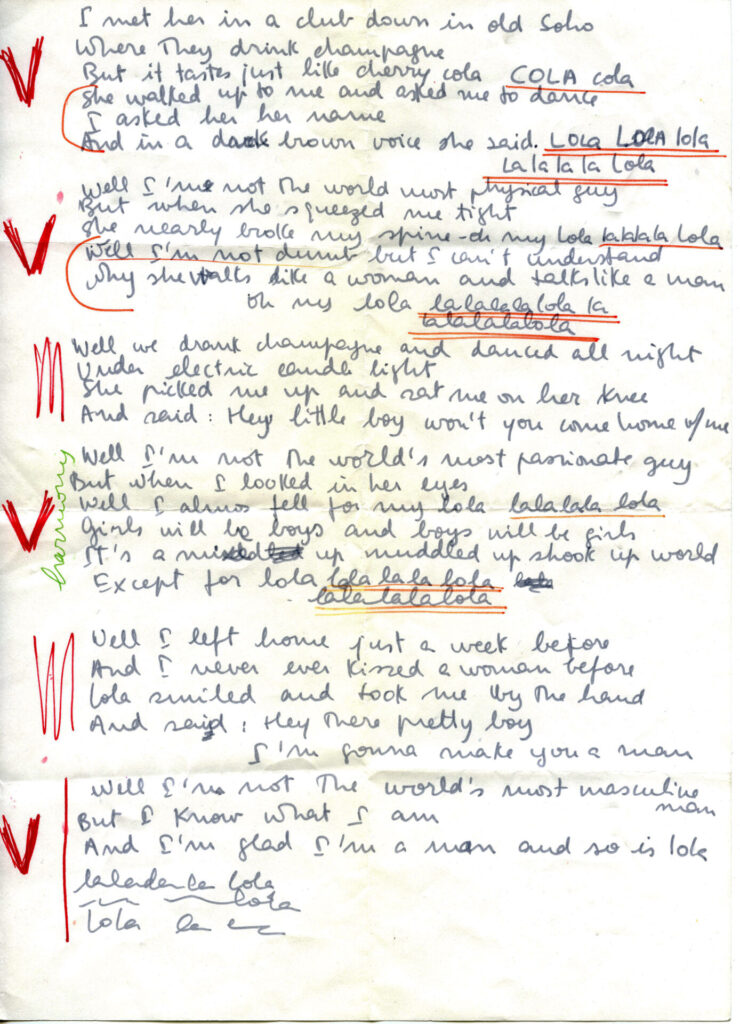

The fight for LGBTQ rights continues, and The Raincoats remain part of the firepower. Their cover of The Kinks’ ‘Lola’ has become a trans anthem, used by young listeners in coming-out videos on Tiktok. Steph Phillips of Black feminist punk band Big Joanie reflects on how ‘Lola’ went “from a feminist reframing” in The Raincoats’ 1979 cover to a song “elicting an interesting conversation about trans identity.” For Kathi Wilcox of Bikini Kill, the song is clearly “queer-positive” and has maintained its sociocultural power into the present. Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill describes it as one among many of The Raincoats’ “protest songs.” With the recent UK Supreme Court recently ruling against trans women and massive attacks on trans rights by the Trump administration in America, The Raincoats remain crucial.

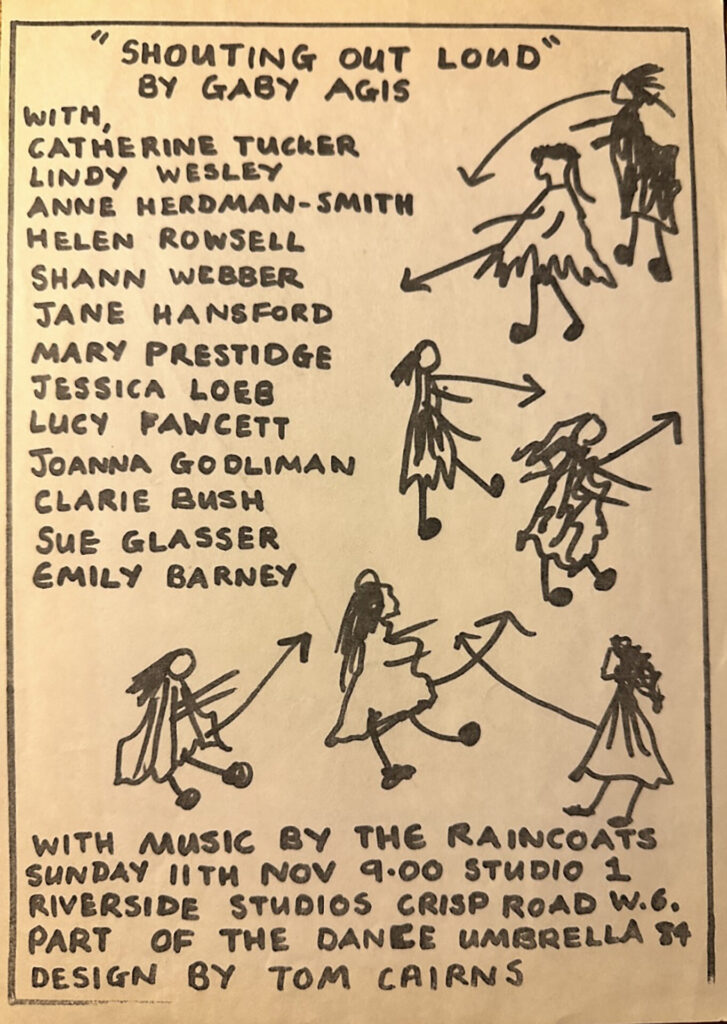

Amidst the twenty-first century slide toward authoritarianism, the reshaping of sonic fortification against government tyranny has continued. For the last forty years, choreographer Gaby Agis has been taken with the message of collective female resistance she heard in The Raincoats song ‘Shouting Out Loud’ which opens boldly:

“Shouting out loud/ a woman alone/ A man/ with fears outside at night/ Singing alone“

She wanted to turn that message into a work of collaborative performance art, which she gave the same title as the song. It was first staged in mid-80s London, with the political backdrop being the Troubles which raged across the Irish Sea; the violent and racist Apartheid government remained in power in South Africa, student activists were “disappeared” standing up against tyranny in the Southern Cone and Southeastern Europe; and the oppressive Soviet Union borders neared a tipping point. “So much of the world we were all inhabiting,” Gaby reflects, “as young women – the chaos, the riots, Thatcherism, all amid the rising anti-racist, feminist movements taking shape and resisting the sense of a world closing inward – it felt pretty gruesome.” By creating her performance piece in collaboration with Ana da Silva, the two artists found a way to flip the political script. “Shouting Out Loud established a solidarity among the performers, and the possibility of tenderness and support,” says Gaby. It revealed how it was “possible to create a feminist community within performance.”

That piece took on significantly greater political stakes in 2019 when Gaby re-staged it in Istanbul, Turkey on International Women’s Day. Gender-based violence and oppression had become tools of strongman Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s regime, and Shouting Out Loud offered a crucial form of resistance. Gaby knew the importance – she’d been teargassed in the city a few years earlier along with other protestors. The Turkish dancers Gaby enlisted to perform the piece experienced a “constant sense of fight or flight,” she says, citing the “layer of threat, and fear of violence that could just spring up when you turn a corner.” In Erdoğan’s Istanbul, participation in a feminist political performance could become a matter of life and death. “Those women needed the piece more than women in other places,” says Gaby. As the piece drew to an end, she and the dancers moved slowly into the street together and walked toward the 2019 International Women’s Day march and were attacked by riot police. Nevertheless, they pushed forth.

Speaking with me in 2023, Charles Hayward, co-founder of experimental rock band This Heat and one-time Raincoats drummer, remained awed by the band’s enduring political import. Whether you’re hearing about punk group Pussy Riot’s 2012 opposition to Russia’s authoritarian regime, or the Grammy-winning Iranian protest song ‘Baraye’, inspired by the 2022 state killing of Mahsa Amini for her refusal to wear hijab, there’s something of The Raincoats music there, he suggested.

“You don’t need to know about The Raincoats to be in a reality where The Raincoats made change and created all the good parts of the reality now, where women have confidence and know they can be loud inside previously male-dominated space,” he added. Female artists using their voices to inhabit such coded spaces, and to speak out against political subordination in all its forms, he suggests, is “testimony to what The Raincoats did.”

Unless otherwise noted, all quotes come from original interviews by Audrey Golden for her new book Shouting Out Loud: Lives of The Raincoats published by White Rabbit in July