"Distance," writes the French philospher Jacques Ranciere in his latest book, "is not an evil to be conquered but the normal condition of any communication." A sobering thought in a time when any kind of artistic endeavour that does not give its audience the opportunity to "interact," no matter how superficially, is inevitably dismissed as "elitist" by the twittering classes. How refreshing, then, to hear of Sonic360’s new series of ‘deep listening’ experiments, entited ‘A Celebration of …’ which ask little more of their audience than to sit down and shut up for once.

American composer Pauline Oliveros coined the term ‘Deep Listening’ only a couple of decades ago as a means of thinking about different processes of listening and learning to concentrate on our acoustic environments. Her Deep Listening Band with David Gamper and Stuart Dempster would choose particularly resonant spaces to play in. And the low-lit confines of Shoreditch’s early eighteenth century St Leonard’s Church provide of course just such an environment for, this time, not a concert, but simply the playback of records by a man to whom such surroundings, and such a ritualistic approach, seem peculiarly appropriate – Florian Fricke, better known as Popol Vuh.

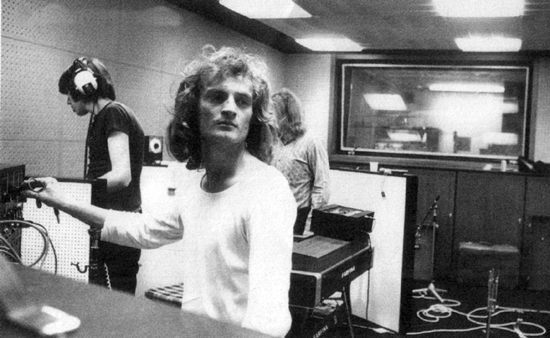

Fricke was born on the Bavarian island of Lindau on Lake Constance, in 1944. The man who would later develop a fondness for namechecking Mozart in interviews and even played Chopin in Herzog’s debut film, _Signs of Life, started piano lessons young and studied at the conservatoires of Freiburg and Munich. It was only upon finishing his formal education, however, that he realised the direction he wanted his music to go in, and the emphasis from the very beginning was on music to be recorded and released, not just to exist on paper. It was at this time, in the mid-60s, working as a music and film critic for Der Spiegel and living in Munich, that Fricke would meet two people who would have a profound effect on his fortunes, his future manager and producer, Gerhard Augustin, and the film director, Werner Herzog.

Augustin remembers Fricke as "a sincere – very religious person – but not so much a Christian believer – more a universal believer in different directions," and in a sense one might argue that the entire Popol Vuh project was an exercise in restoring music’s lost auratic, ritualistic qualities. But if Fricke’s music tends to be associated with a certain kind of sublime pastoral excess, this may be in large part due to its use in the films of Werner Herzog. One of the leading exponents of New German Cinema in the 1970s, Herzog once pledged to go down to hell and fight hand to hand with the devil himself if his fil required it so, and, with a series of films starring Klaus Kinski (Aguirre, Fitzcarraldo, Cobra Verde, etc.), established himself as perhaps the quintessential director of the operatic struggle between an iconoclastic Wagnerian hero and an indifferent if awe-inspiring natural world.

Meeting Herzog in 1967, Fricke would go on to either act in, or provide music for, all of Herzog’s most significant films in the 70s and 80s, idelibly linking the pair in the public consciousness. But, as pointed out by K.J. Donnelly, the music of Popol Vuh rarely fulfills the traditional function of music in Hollywood films, building tension and heightening the audience’s emotional investment in the characters – indeed, the music is rarely associated with any onscreen characters at all, but acts rather as a kind of overture or intermezzo. Herzog’s Woyzeck is very different from Alban Berg’s, but the music does at least share a certain pungent thickness, a coarse violence that refuses reinscription in any normalising discourse.

A classically trained pianist who chose to form a band rather than conduct an orchestra; playing a mixture of rock (guitars, drums, synthesizers) and nonrock (oboe, tambour, massed voices) instruments; practising improvisation but favouring ancient or exotic scales; a pioneer of electronic music who gave away his synthesizer (to Klaus Schulze) after two albums which predicted many of the most significant trends in the pop music of the next twenty years (from ambient music to the Burundi beats of British post punk); Popol Vuh’s music exists in a curious hinterland between the worlds of rock and contemporay composition, a grey area that had hitherto been dominated by the world of easy listening.

Having been taught composition by the brother of Paul Hindemith, inventor of Gebrauchsmusik ("functional" or "useful music"), Florian Fricke in fact shares with the purveyors of mood music a great many concerns: the exotic fascination with faraway lands of Martin Denny, Les Baxter and the 101 Strings; the massed voices and Gregorian influence of Ray Conniff and the Swingle Singers; the use of found sounds and field recordings of Frank Clacksfield; the space-age sounds of Gershon Kingsley; the mysticism and promised healing properties of Andreas Wollenscheider’s New Age music. However, as in film so in other contexts: Popol Vuh’s records will never quite co-operate with an assigned role as background hum. The music has an unsettling quality, almost despite itself. Like Erik Satie’s Vexations, a disquieting sensation arises from a place you can’t quite pinpoint, all the sonorites seem in themselves perfectly pleasant but something about their combination and juxtaposition renders them uncanny. The more the sounds withdraw into their own beatitude, the more they seem to gnaw at you.

Popol Vuh, then, is uneasy listening, but like all the best mood music it envelops you in its own sound world, cocooning the listener in waves of sound. Fricke rarely played live and submitted to few interviews but inspired a kind of cult-like devotions amongst his fans. One of his very last projects was an audio-visual installation based around the myth of Orpheus – perhaps the ‘cult’ musician par excellence, of whom it was claimed his music could coax the trees and rocks into dance. He referred to the acoustically designed chambers of the installation as "good rooms", explaining in a contemporary interview, "We hear so much that we don’t hear anything." Now, as music becomes increasingly the atomised personal soundtrack to every mundane activity, the music and ideas of a soundtrack composer for whom music was never background music, and always inseparable from a community of the faithful, from site and from ritual, may prove to be a much needed corrective, or cleansing purgative.

all was in suspense, all calm, in silence; all motionless, all pulsating, and empty was the expanse of the sky. [from the 1st book of the ancient Mayan text, Popol Vuh]A Celebration Of Popol Vuh takes place in St. Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch, this Thursday February 25th