In 2016 I rewatched the 1982 Jim Henson film The Dark Crystal film and had a musical epiphany.

I first watched it in 1988 with my grandparents on VHS cassette and I saw it again when I was 16 or 17. So I have seen and heard it three or four times in my life, but the last time it struck me that a lot of the music on the film was a sound that I have been unwittingly trying to capture myself for several years.

My music lives between tradition and improvisation, between early and contemporary music and so too does the soundtrack to The Dark Crystal, with its real and imagined landscapes and sounds. A large part of the epiphany stemmed from how the film introduced me to double recorder playing. This is a technique which feels very natural to me even though anytime you play more than one instrument simultaneously you run the risk of seeming gimmicky or even a joke. But I have a genuine conviction that this is an intrinsically beautiful sound which stems from the double pipes of the ancient Greek instrument, the aulos. The technique feels like it completes the instrument and echoes a strange tradition which feels very familiar, despite being rarely seen or heard now. I would describe the sensation as listening to something you know you have never heard before but it is familiar to you; part of your collective folk memory.

I taught myself how to play the double recorder when I was studying for my music A-level in the 1990s but it was only when I saw The Dark Crystal again in 2016, that all of this music began to make complete sense. The soundtrack was embedded in my ears and heart, with its familiar yet exotic sound, somewhere between early music, traditional Celtic, medieval and baroque string orchestral. After reconnecting with it I felt like my life in music made more sense, and it was nothing I could have learned at school or college. The exciting small ensemble interludes between the orchestral suites which identified the characters, such as Podling, Gelfling or Scecsis, were mind blowing. It made me feel like there was room for this sound in the contemporary music landscape. When I saw and heard the double pipes in the film in 2016 I knew that I had somehow learnt and absorbed this music, and had been trying to find my way back to this magic for years and years.

I hadn’t been trying to find my way back to it so that I could copy or repeat it, but so that I could feel the kindred musical sounds in a musical world where I had always felt singular, not part of how other people were making music. Realising that I needed to ditch the idea of fitting in and to focus on making the music I wanted to hear. This is one of my favourite sayings and pinned up in my music room. It’s also the best advice I can give anyone making music, "Make The Music YOU Want To Hear".

It turns out the music I want to hear was planted in my head at the ages of 8, 16 and 36 and I am only discovering how a few moments of listening have shaped my life. I still don’t think I can tell you what the full storyline of the original The Dark Crystal is because to me the music has always overpowered sense especially through its small folk ensemble minimalism. You don’t need much to release your imagination, a small melodic passage, a motif, a signal and you are transported to a new world.

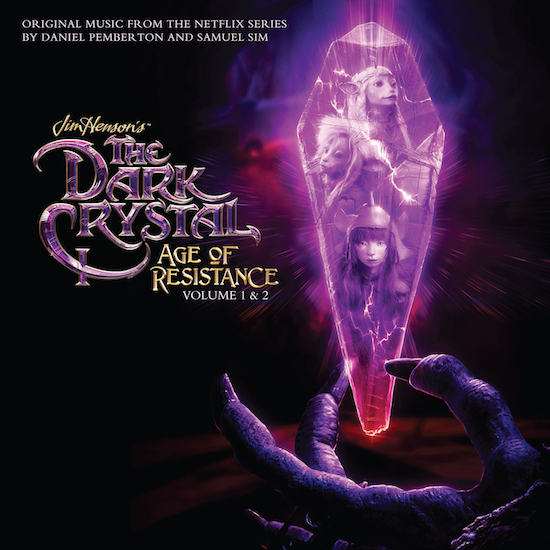

Early next month, Music.Film is releasing vinyl versions of both volumes of The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance, containing some of the music from the recent Netflix series, which was a prequel to the film.

It continues the remit of using early instruments alongside the orchestral, the new composers of the 2019 prequel Daniel Pemberton and Samuel Sim having given themselves certain limitations. For example they shaped the music by choosing not to include a grand piano, thus playing with traditional ideas of balance. The omission of the instrument was a conscious decision, it isn’t part of the sound world of Thra, which leaves this space more open to unequal temperament rather than locked into the Western scale on black and white carefully measured notes.

A hollow, woody, wide bore-sounding recorder soars above an orchestra. This can’t happen in a real orchestral setting, and it is one example of how the composers turn balance and pitch on their head. The magical sounds of unusual and ‘creaky’ early instruments hold their own over the bed of strings. This element also feels like the narrator; it sets the scene, it tells you if you can relax or if someone or something ominous is around the corner. The strings are there to make you feel safe but they are also spritely and tricksy. There are details which make the soundtrack speak of an earlier alternate universe, such as the colours and textures and employing little or no vibrato in the traditional instruments which give a pure innocence at all the right moments.

Brittle plucked strings are pitted against smooth legato passages cutting floating atmospheres. There are so many interrupted endings, senses of unease which are conjured by sinister spiralling unearthly sounds that crash into epic flutes which are suddenly dropped five octaves down.

The composers haven’t relied on regular instrumental pitches, they make a terrifying and craggy new world which feels organic and familiar, but you won’t find the instruments to make these pitches for sale in any normal music shop. Samples of acoustic instruments are manipulated, magnified to experience every sine wave and microsecond of texture.

Pemberton and Sim have brought experimental music into a mass audience territory through this soundtrack. They have turned detuned cello, wineglass samples, old creaky medieval instruments into the folk music of a different planet. Now that this door has been opened, people could go deeper and listen to Lucy Railton’s Cello, Andie Brown performing her on giant wine glasses and electronics or the composer/performer Stevie Wishart cranking brittle shapes from a meta-hurdygurdy to hear the origins of such ecstatic explorations.

Field recordings are integral to this release and I can’t help feeling that the recordings of metal sculptures that the composers sampled on a snow covered mountain were in the shape of the main characters of Age Of Resistance.

It’s not unusual to use ancient instruments to create new music and I’m declaring a personal interest here. After all in order to create a new world we can first start with what it sounds like, which in this instance means combinations of recorders, nickelharpa (Swedish keyed fiddle) and sub bass flutes.

So much of this music is emotional and uses the messa di voce singing technique which relies on the vocalist sustaining the same tone but increasing or decreasing the volume. This happens so many times throughout the sound track, and I defend it to the end, the tension and suspense in texture tells enough of a story on it’s own.

The dissonant clashing chords of ‘Into The Catacombs’ echo with water dripping wind harmonics creating sounds of wailing animals down tunnels, my only sadness is when the rhythm becomes a regular beat, like when Jordi Savall the great grandfather of the viola da gamba brings a percussionist in to an otherwise wild and intoxicating piece.

‘Dzenpo!’ is a recorder, drum and crumhorn dance, which pushes one into the waistcoat-clad danger zone of earnest early music. I don’t want to be rude about it, but it makes me cringe when I imagine a band playing this style of music, but if I think in the context of what it is accompanying I can try to get on board with these sounds representing an other worldly culture. It’s the functional dance music of a ceilidh; the equivalent to the music played by the cantina band in Star Wars. Not all traditional tunes are the best, but they have a role to play. I love that recorders are integral to The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance, but in a similar way to their representation in baroque music, these instruments are often used to personify the pastoral, but I would argue they can be as moving as the strings en mass.

‘Song Of Thra’ almost lulls you into an epic familiar string zone, the type which features in so many movies but in this case, just as it reaches its golden section, when you think you can predict the rest a new texture and grit appears and you remember that this planet has magic and sorcery and otherworldly sounds and creatures. Almost every piece has huge heartstring tugging motifs, and it’s hard not to respond to the blood pulse and pounding rhythm of ‘Together We Fight’ with its sudden drop to silence and tears, the shimmering calm after the storm. This piece is everything, it is complete.

I find myself physically leaning in to ‘The Blue Flames Part I’, I want those untuned underneath parts to emerge more, give me more of the crunchy slurs and glissandos which happen only at the very end, it’s worth the wait though. ‘The Hunter + The Storm’ and ‘Dreamspace’ are complex and full of sound critters scampering from ear to ear in the mix, based on source recordings of crickets which have been slowed and manipulated. Exciting and rousing tracks, they live somewhere between the raw circular breathing and foley sounds of Colin Stetson’s saxophone, and a performance I recently saw of Oliver Coates and 20 cellos at The Southbank’s Deep Minimalism 2.0 Festival.

The threat and danger of Thra is ever present, almost as soon as you feel safe the sound is twisted, the ground beneath you falls away. Every time there is epic drama there is a cut to the small stature of the Gelfing encouraging small but powerful and beautiful sonics.

‘The Pod Dance’ on the original soundtrack is high energy virtuosic recorder in medieval Italian Saltarello style, we also have to remember that the new OST is a prequel so which that logic when the world of The Dark Crystal is more established. This is not simply the work of male composers sitting at the piano, they have searched out the folklore and folk music of this imaginary world and have discovered ways to help it express it’s barren and craggy tundra to give it a voice.

Sparked by listening to this new release I have been sucked back into the original original soundtrack to the film and my advice is to listen to everything. Some of the field recordings and early musical instruments which influenced The Dark Crystal film composer Trevor Jones are completely essential to understanding where the new soundtrack has come from. Jones employed the use of instruments which spanned five centuries, one of which is English Regency instrument the double flageolet, which is actually the correct term for the double recorder.

Daniel Pemberton and Samuel Sim have stuck to this innovative blueprint, right down to re-inventing instruments through which they continue The Dark Crystal tradition of developing instrumental sounds by manipulating and experimenting to create music for sounds which can only exist in a world inhabited by Gelfings and Skeksis.

The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance is released on vinyl on February 7 d