In the latter half of the third century, with the Roman Empire teetering on the brink of disintegration, a strange phenomenon began to occur in what is now the Valley of Natron in the Egyptian desert. Solitary figures began to arrive and inhabit the inhospitable terrain. These Christian hermits came to be known as Desert Fathers and Mothers. At first, scattered across the landscape with minimal connection to each other, they shared little more than their mutual adherence to an extreme form of ascetism. They had, as they saw it, escaped the temptations of the unholy cities of man and entered, as the Bible had counselled, into communion with God where He could be found – in the wilds.

It was a hard bleak existence; spending years where even Christ had only spent 40 days and 40 nights. Yet, as civilisation became more unstable and uncertain, more and more pilgrims joined them and paradoxically the monos (those in a singular relationship with God) spread in popularity as they spread geographically.

Gradually, an odd kind of celebrity began to take hold and with it a climate of competitive suffering. The more agonised one was, the thinking went, the closer one was to the divine. Some of the desert monks sought to outdo each other in acts of audacious masochism. Hairshirts were worn. Flesh was flagellated. At first, it was enough to live in a barren cave but that became seen as too luxurious when compared to a competitor who could barely crawl inside his hovel, or later stylites who rejected shelter entirely and lived at the top of pillars. A month of silence did not hold much weight compared to a rival who kept a stone in his mouth for three years so as not to speak a word. Abstaining from food paled next to a neighbour who abstained from water.

So committed were some Desert Fathers that they lost track of why they were there entirely, and began to dwell more in the realm of appearances than transcendence. All of the penitents would claim to be dedicated to escaping the sinful ways of distant metropolises, and to policing their thoughts and desires accordingly. Yet the old human familiars of ego and insecurity had accompanied them to the desert.

Centuries later, an astonishing sub-genre of painting came into being, focusing on the trials of the greatest of all the Desert Fathers – Anthony the Anchorite. They depict the saint besieged by, and resistant to, incarnations of all his worldly temptations. Some of the paintings focus on a single urge, with questionable outcomes. Choosing greed, Lo Scheggia‘s otherwise charming Giotto-esque depiction of Saint Anthony running away from a boulder-sized nugget of gold is inadvertently hilarious. Choosing lust, Paul Delaroche‘s 1832 harem-like effort and Lovis Corinth‘s 1897 bacchanalian depiction, with an appalled Anthony cowering in the middle of a rampant hoard of nymphomaniacs, have all the power and tragedy of say Ned Flanders accidentally stumbling into an orgy.

The genre comes alive though when all the deadly sins are present and are portrayed as unstable and inscrutable as they might appear to they who are tempted. The point being, we often don’t even know what our impulses and intentions are, given how successfully we lie to ourselves. Martin Schongauer‘s Torment Of Saint Anthony engraving (copied by Michelangelo no less) has the hermit suspended high in the air, being pulled apart at the seams by demons; a reminder that the artists were contemporaries of Hieronymus Bosch.

This surreally satanic and chaotic perspective took off, partly because it allowed artists to give free rein to their darkest imaginations, much in the way diabolically villainous roles can delight actors with their mix of camp horror and childlike playful ingenuity. In 1594, Maarten de Vos had Saint Anthony held aloft by an idiosyncratic series of devils, each worthy of a backstory. Jan Brueghel the Elder has them gathering at Anthony’s cave like an unwanted Comicon. The Surrealists, of course, loved the hallucinatory quality of the legend with Dorothea Tanning‘s billowing whirlwind of flesh rising above the saint proving convincingly nightmarish, and not even his ubiquity on student walls dims the weirdness of Salvador Dali‘s depiction of the naked Anthony just about standing his ground against colossal spindle-legged horses and elephants with towers on their backs (as with all weirdness, the most effective has a history in reality – in this case the traditions of howdah and war elephants).

It may seem strange that Saint Anthony survived into the modern age – when it appears, some would argue, that God didn’t – but this would be forgetting that we are in a golden age of both temptation and delusion. The methods of the Desert Fathers, and the respect once afforded to them, are also still with us. There is still a lot of currency to be gained from heading off into the wilds, living ‘authentically’, returning with something that has tapped into and been sanctified by some animist spirit of the wilderness (Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago for example) or being canonised by dying out there in the sentimentalised backwoods like Christopher McCandless.

Like any other urban degenerate, I’ve laughed at such figures for their naivety and indulgence, while simultaneously fixating over the time Wittgenstein went and lived in a shack in the middle of nowhere or when Nietzsche hiked in the Alps or Nan Shepherd or Bruce Chatwin or whoever buggered off to wherever and I’ll retell the stories second-hand in pubs in shipless docklands to friends who resemble bearded lumberjacks and trawlermen convinced we’d be one of them, the solitary geniuses wandering above a sea of fog, and not one of the ‘phonies’. Inauthenticity pulls at our souls, ragged as any airborne Saint Anthony, just as consumerism and life online and the media and desire and envy and a thousand other new and ancient demons do.

Yet wildernesses do have a formidable power in terms of stripping away distractions and focusing attention on the essence of life, consciousness, and their possible meanings. It’s no accident that prophets, and continent-conquering religions, were often forged there. There’s little question that contemporary humans benefit psychologically if not spiritually from, at least temporarily, escaping the inundations of metropolitan life, "far from the madding crowd’s ignoble strife" as the poet Thomas Gray put it. And yet, in a confirmation of the fact that there is nothing human beings cannot spoil, the closest we have seen to a Desert Father in recent times, a figure increasingly seen as a warped icon, is the very embodiment of ignobility and strife. His name is Ted.

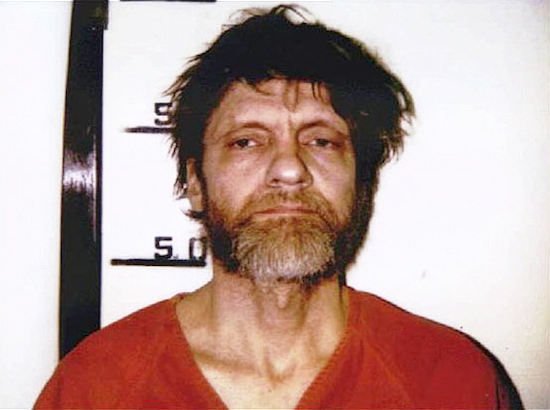

Theodore Kaczynski was a deep thinker, a Harvard-educated mathematics professor no less, who abandoned civilisation for the ascetic purity of the wilderness, living out his days in a tiny austere cabin without electricity or running water in the Montana woods. From there, he railed against a fallen mankind whose weakness, in terms of machines and psychology, would condemn the entire world. He was a modern millenarian, a secular anchorite and, perhaps to himself but certainly to a growing chorus of others, a prophet. The crucial difference between Ted Kaczynski and the Desert Fathers of old was that Ted was a psychopathic murderer.

This month, Blanck Mass released an original score for the forthcoming motion picture Ted K. The track ‘Montana (Main Theme)’ is incongruous on first listen. It has a brooding industrial quality, full of menace, but there’s an odd, though acknowledged, Leone-era Morricone influence in the background voices and the flourishes that feels discordant. Blanck Mass’ ambiguous approach is telling, with its mix of palpable malevolence and this jarring pseudo-heroic chorus, voices that pulse as incessantly as machinery in the background, echoing the death-drive of a self-destructive society or a compulsive mind in a similar downward spiral. Its just the latest in a litany of appearances Ted K, or the Unabomber as he was named, has made in music.

He’s been referenced in hip hop (Eminem, J Cole, Master P), garage punk (The Donnas’ ‘I Wanna Be a Unabomber’), Detroit techno (Underground Resistance) and so on. Much of which could be put down to callow swagger, in the same way Axl Rose strutted around stage in cycling shorts, bandana, and Charles Manson T-shirt (a countercultural ‘icon’ whose cult found relevance by butchering a heavily pregnant woman among others). Ted K has the added mystique of intellectualism, which makes him a gift for those seeking cheap radical credentials as well as those simply trolling. Other songs, like Fat White Family’s hypnotic ‘I Believe In Something Better’, toy more ambivalently with the subject, where the provocation has another purpose, unsettling for sure but at least leading somewhere, even if it turns out to be an Arcadian abyss.

The first time I became aware of the existence of the Unabomber was through such a song. Like any good autodidact pleb, I’d enrolled in the university of the Manic Street Preachers as a young teen, and, to my eternal gratitude, they introduced me to many writers I later became obsessed with – Camus, Plath, Primo Levi, Henry Miller, R.S. Thomas, Octave Mirbeau, Raoul Vaneigem etc. The coming-of-age ritual of being handed on knowledge was tempered by the realisation that it meant eventually outgrowing the certainties of youth. The Manics understandably changed after Richey Edward’s harrowing decline and disappearance, most evidently heard on the melancholic This is My Truth… Tell Me Yours album.

One of their b-sides from that time showed another way they’d transformed, and not just in the oblique electro-tinged aspect to the music. The band never lost their magpie’s eye for a morbidly fascinating story but although ‘Montana / Autumn / 78′ is a song about the Unabomber it has none of the provocateur/puritan streak that Richey had towards distinctly toxic characters from Filippo Marinetti to Patrick Bateman to Valerie Solanas. It begins in their familiar fragmentary way ("Luddite lover/ Forgiving father") but it is much more qualifying than before; compare the "You’ve ruined more than you’ll gain/ Know what you mean – but not what you do" lyric to Edwards’ ‘Archives Of Pain’, "Don’t be ashamed to slaughter/ The centre of humanity is cruelty". When you are badly burned by experience, you learn the intrinsic value of what is lost. It is no longer a game or a pose. As one of the Manics’ icons André Breton put it, after the Second World War, the Holocaust, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, "We no longer want the end of the world." The theatre ends when shit gets real.

Youth has many virtues and also vices – the temptation to mistake darkness for depth, callousness for decisiveness – but youth is also eminently forgivable. It is less easy to excuse those who are old enough to know better, who know that radical means going back to the roots rather burning down trees, who know the enemy of an enemy is not automatically a friend, and that ends do not justify the means but rather means corrupt the ends. Ted Kaczynski’s appeal has only grown with time, due to misplaced romance and expedient alliances against the technocracy he opposed, a mix of radical chic and edgelord snark, both of which are ultimately forms of cosplay. It is also fuelled by a resurgent true crime industry that, with thinly veiled indifference towards living survivors and grieving families, wallows with salacious pleasure in the agony of others and elevates the mystique of predators. Ted K is placed somehow deferentially above this squalor. Articles abound online by ‘acolytes’ proclaiming Kaczynski to be an ‘epic hero’, as if he were no more than a latter-day Thoreau. Let’s assume, as some do, that he was a prophet, of what exactly? To fully understand, we have to look at what Ted K did rather than simply what he said he stood for and against.

On 25 May 1978, a package was found in the car park of the University of Illinois. It was sent on to Northwestern University’s Professor Buckley Crist Jr, whose name had been written on the return address. It wasn’t familiar, upon arrival, so he began to open it. Under the wrapping, he discovered a wooden box with a small door marked ‘OPEN’. The professor sensed something was wrong, initially suspecting a misdirected shipment of drugs, so he contacted campus security. A police officer arrived and duly began to unpack the parcel. Crist recommended pointing the little door away from him, just in case, and sure enough it exploded. Thankfully no one was seriously injured. Two years passed and a cigar box was left outside the office of a graduate student John Harris. He picked it up, intending to keep stationary in it. The detonator exploded with a flash, but the explosives mercifully remained intact.

A similar malfunction saved the passengers and crew of American Airlines Flight 444 from Chicago to Washington, D.C. A bomb in the hold failed to fully go off but filled the cabin with smoke. This was followed by an explosive device sent to the home of the United Airlines president inside a hollowed-out copy of the WW2 novel Ice Brothers by Sloan Wilson, seriously injuring him upon opening.

The attacks marked the beginning of a spasmodic almost twenty-year terror campaign. It was waged against academics, airline companies, scientists, corporations; targeting symbols of the technocracy that was supposedly despoiling the earth and corrupting minds. What it really meant was the mutilation and traumatising of human beings, often secretaries and students. Fingers blown off, faces burned, bones fractured, eyes damaged, arteries severed, shrapnel driven into bodies at high speed and with immense force. Three people were murdered. A computer shop owner by the name of Hugh Scrutton in Sacramento. An advertising exec in New Jersey called Thomas Mosser. The president of the California Forestry Association William Dennison. In a perversely revealing ‘behold the man’ passage, Kaczynski wrote of the first of the fatalities, "Experiment 97. Dec. 11, 1985. I planted a bomb disguised to look like a scrap of lumber behind Rentech Computer Store in Sacramento. According to the San Francisco Examiner, Dec. 20, the ‘operator’ (owner? manager?) of the store was killed, "blown to bits, on Dec. 12. Excellent. Humane way to eliminate somebody. He probably never felt a thing. 25,000 reward offered. Rather flattering."

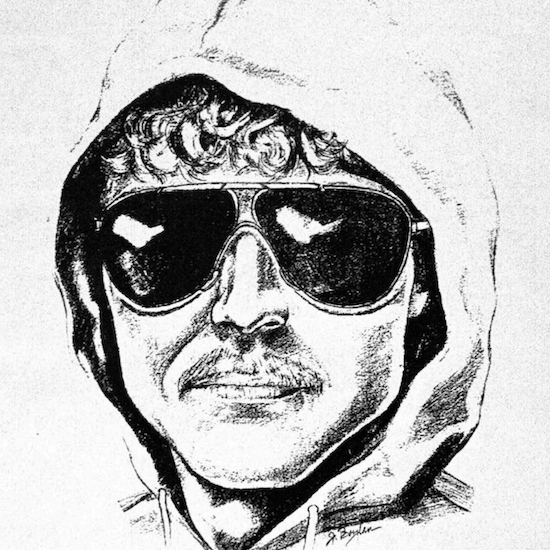

What seems to elevate Kaczynski, in the view of some admirers, beyond lesser psychopaths, is his manifesto or as he named it, Industrial Society And Its Future. This was published by the Washington Post and the New York Times after he essentially held them to ransom, threatening to take more lives if it wasn’t released. The FBI gave the newspapers the green light hoping, correctly as it turned out, it would lead to someone identifying the perpetrator. Whatever mystique the Unabomber Manifesto might have does not survive its reading. It is 35,000 banalities, a muddled diatribe that says more of its author than it does the past, present or future of society.

What is genuinely surprising, and this is where its truly prophetic qualities begin, is how oddly normie it seems. Perhaps this was different at the time of its publication. Perhaps Kaczynski had some impact on the mainstream after all. Or perhaps capitalism has an irresistible ability to pull extreme positions in from the margins and absorb them. The opening paragraph could be an innocuous press release for virtually any NGO/

thinktank/ activist group now or any number of writers across the political spectrum from Roger Scruton to Noam Chomsky, John Gray to Naomi Klein, though as we shall see there is a crucial difference in intention: "The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world."

What is evident throughout the manifesto is how much of a cliché it is, how toothless compared to the brutality of Kaczynski’s actions. There are tepid rants against ‘leftism’, arguing that it is built upon ‘feelings of inferiority’ and ‘oversocialization’ that suggest were he to have emerged now, with such half-baked opinions, he’d have earned himself a podcast or a ‘contrarian’ newspaper column rather than a jail cell.

Nowhere does he penetrate deeply, paling even next to someone like Christopher Lasch who deciphered the latent narcissism within certain elements of the left. Instead, Kaczynski takes the work of the admirable Anarcho-Christian thinker Jacques Ellul, particularly The Technological Society, and desecrates it, removing both conscience and discernment. Kaczynski passes over genuine opportunities to exert critical thinking and prophecy; predicting the corporate co-opting of progressivism would be a start, for instance. He skims continually across the surface, blaming the left for the modern ills of "boredom, demoralization, low self-esteem, inferiority feelings, defeatism, depression, anxiety, guilt, frustration, hostility, spouse or child abuse, insatiable hedonism, abnormal sexual behaviour, sleep disorders, eating disorders, etc” but paying little heed to entire billion-dollar industries designed to profit from the manufacture of insatiable self-obsession and inadequacy on industrial scales or the commodification of every aspect of life.

At times Kaczynski appears almost naïve, believing the performance of masochism among activists to be sincere for example, but ultimately he is incapable of meaningful critical thinking because there is no possibility of self-examination. He displays pettiness throughout towards pet peeves and strawmen but also demonstrates a curious desire to be liked (at times taking care to point out he is not racist or misogynist). His urge to be seen as reasonable is astonishing. "As for our constitutional rights," Kaczynski writes, "consider for example that of freedom of the press. We certainly don’t mean to knock that right; it is very important tool for limiting concentration of political power and for keeping those who do have political power in line by publicly exposing any misbehaviour on their part." You have to continually remind yourself you are being lectured to by a man who demanded his screed be published or he’d continue to detonate mail bombs in strangers’ faces or perhaps bring down a passenger plane or two.

This points to the heart of why Ted K really was prophetic, though not as he intended – the chasm between self-obsession and self-awareness. When Guy Debord and the Situationists proposed The Society of the Spectacle, the veil that capitalism pulls over our eyes, the idea was a relative innovation. Mass communication was still finding its feet and pysops were clumsy enough to appear authoritarian rather than to present as allies. Today, we have a very different world and sadly not only for the Situationists but the rest of us, their legacy is one again of absorption.

A case in point, there is no group anywhere on the political spectrum that is not gnostic now. By which I mean, that every single position from furthest left to ‘moderate’ centre to furthest right believes they are the sole possessors of hidden conspiratorial knowledge, and that every other position are dupes. All are anti-establishment now, including the establishment. All are mavericks and rebels, especially those who prop up the status quo. That’s not to say that there is moral equivalence across the board but when every party believes it has uniquely awoken or been [insert colour]-pilled, we have to accept that the Spectacle has absorbed the very idea of escaping the Spectacle. To put it another way, we escape Plato’s Cave and are celebrating our liberation in another cave, perhaps one where we make the shadow puppets but a cave nonetheless. Or to put it another way again, as the sideshow trick goes, the most credulous marks are the ones who think everyone else is a mark.

Ted Kaczynski is hard to place on the political spectrum. Is he an anarchist? A fascist? A luddite? A classical liberal? A fanatical ecologist? An alt-right prepper? Perhaps that inability to fit is instructive; another piece of evidence, alongside billionaire ‘populism’ and bourgeois ‘socialism’, that basing everything political on the seating arrangement of the National Assembly of the French Revolution has been a mistake. One of the reasons Kaczynski fits everywhere and nowhere isn’t because of vagueness but rather something more troubling.

Nihilism is evident in every movement, however apparently benevolent. At the very least, it is a pertinent omnipresent risk. The rot sets in quicker than people think. It’s there in moral expediency, in hypocrisy, in the blind eye, the kickback, the nepotism and the untruth, in the justifying of unjustifiable things, in the abstraction of human life and suffering, on and on until what you espouse, truly espouse beneath language and posturing, is no better than what you opposed. It is there, embryonic, in Malthusian anti-natalists who want to save the planet but believe human beings to be nothing but a cancer. It is there in accelerationists who wish to make things worse so they will miraculously get better. It is there in a much more developed, powerful and grotesque sense in companies that despoil the earth and degrade its people under a green or rainbow camouflage. All have a religious character. Truth, by contrast, is not just what they do not want you to find but also what you do not want to find. For all the cultural relativism in the world, which Kaczynski rails against in his manifesto, there are few ways of grounding in universal reality more effectively than following the money or remembering the dead bodies. Some of us have seen it before; when, for example, freedom fighters take mothers off to be shot, and the chorus applauds or covers up from a safe distance. Over and over, it happens, and everywhere. In this sense, Kaczynski is mundane, both disruptive and mundane. He is what goes wrong with idealism. And those who celebrate him might as well worship rust.

They found a library of books in Kaczynski’s cabin. For all his hyper-intelligence, the point of many of the volumes – 1984, Darkness At Noon, The Stranger, The Trial – was entirely missed. In his copy of The Brothers Karamazov, Kaczynski would have found, and likely passed over, the following passage, "Imagine that you are creating a fabric of human destiny with the object of making men happy in the end, giving them peace and rest at last, but that it was essential and inevitable to torture to death only one tiny creature – that baby beating its breast with its fist, for instance – and to found that edifice on its unavenged tears, would you consent to be the architect on those conditions? Tell me, and tell the truth." Whatever his experiences, whatever his justifications, he consented to these conditions.

For all the temptations that awaited the Desert Fathers, the two virtues which they held above all others were the fear of God and crucially humility, knowing that if followed this would prevent the path to corruption and hubris that would follow. It enabled them to leave the world no worse than how they’d found it. "The Fathers of the Church were not afraid to go out into the desert because they had a richness in their hearts" wrote Franz Kafka, another of Ted K’s chosen authors, "But we, with richness all around us, are afraid, because the desert is in our hearts." Before anything else could be achieved, they set themselves the task of knowing themselves, however painful. Only then could they guard against the real deadly threat of solipsism, the temptation that led Ted K to the woods, to his prison cell, and others to their graves.