It’s the late 1650s and these are dark days in England. As many as 200,000 people have died in the civil wars and their aftermath, including a now decapitated king. The regicide and Butcher of Drogheda, Oliver Cromwell is also among the dead, but his corrupt puritan regime will joylessly stagger on for a while longer. The theatres are still shut, no sports are permitted. Drinking is frowned upon and many inns have closed. Cursing, immoral dressing and working on the Sabbath are gravely punished. Christmas is banned. The writer John Milton has been a loyal supporter of the new order, and rewarded with the position of Secretary for Foreign Tongues. He will go into hiding when the regime falls, and the regicides are hunted down by the dead king’s son but that has yet to pass. For the moment, Milton is writing his epic Paradise Lost. Or rather, given he is now completely blind, he is dictating it wholesale to friends, family and amanuenses. In this sprawling work, he recounts the Fall of Man – Adam and Eve ejected from Eden – parallelled with the destiny of Satan, the rebellious once-beloved angel, expelled from heaven, “hurled headlong flaming from the ethereal sky”.

It’s the mid-1990s and these are dark days in England. The Tories have been in power since 1979 and the country has been gutted, deindustrialised and sold off. Thatcher has been ousted but the corrupt puritan regime will stagger on joylessly for a while longer. With John Major’s government mired in sleaze and hamstrung by incompetence, Labour are poised to finally topple them, but leader John Smith dies of a heart attack and is replaced by public schoolboy Tony Blair, with rictus grin and ‘modernising’ plans already in place. Throughout this age of conservatism, culture has been repeatedly revived by young people themselves, via DIY guerilla means, but they have been under concerted pressure, culminating in the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994. This sought to crush outdoor impromptu dance events, increasing police powers in an effective war against soundsystems, raves and electronic music. Something had to give.

The desire for change and breakthrough was organic and essential. The way it transpired, less so. It was easy to be carried along by the momentum of ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Star’ and the enjoyably androgynous disco of ‘Girls And Boys’, especially given the angst of Grunge was now consuming itself. Definitely Maybe became the fastest-selling debut ever in the UK, up to that point, while Parklife sold over a million copies. Yet the ‘movement’ that followed was a contrivance from the beginning, cobbled together by a largely moribund press, under the risible, vacuous title of ‘Britpop’. It would not be long before the welcome charisma, swagger and hedonism of Oasis became a self-parody, the goodwill squandered with coked-up recording sessions, sleb-strewn parties, bloated egos, paparazzi skirmishes and creative redundancy, all draped in the Union Jack. Their spirit was always key to their appeal, unapologetically defiant underdogs, but it was always way ahead of their sound, with its plodding funkless sexless bassless rhythms (only ‘Columbia’ contained the slightest hint that anything like the Haçienda had once existed), thick walls of execrable guitar, paint-by-numbers lyrics lacking any of the hilarity and charm of their interviews, and the aping not of The Beatles (whose inventiveness would have been a godsend) but the also-ran fag-ends of glam rock.

After a volte-face from baggy/ shoegazey origins, there was something similarly off with Blur, a boisterous stage school callowness that eclipsed islands of brilliance (‘To the End’, This Is a Low’ etc.), at least until heartbreak and Pavement saved them. The other bands who made up the numbers were mostly journeymen, trading on authenticity while simultaneously pilfering earlier superior fare, from The Kinks to Wire; an unnecessary regressive betrayal of the underground youth movements at the time and of youth itself. Though rewritten now in the latest profit-driven Ticketmaster wave of revisionist nostalgia, the prevailing insistence then that we all somehow should have been born earlier was particularly revolting. Certain bands and their disciples seemed determined to convince us all that we’d somehow missed out on our youth because we’d been born too late to see The Small Faces in their prime, and so pranced around like extras in Quadrophenia, a copy of a copy of a copy. Added to this was a bourgeois media set, who covered their origins and banality by promoting and cosplaying their own jaundiced projections of working-class culture. Not the inventiveness and glamour of earlier ages – say Roxy Music, for instance, or post punk or even the scene around Factory Records – but laddish posturing, leering misogyny, football chants with none of the soul of ‘the beautiful game’, mindless hero worship and mimicry, the narrowest of sonic palettes, proud philistinism, and knuckleheaded mad fer it babble. Britpop can’t be blamed for the fall of Rome alas but the transition of London’s image from a place where countless new musical genres were being broadcast on pirate frequencies from tower blocks, where bottom-up art scenes could afford to thrive and move through the city, to a two-tier priced-out Richard Curtis-spun Stage English playground of nightmares happened during this watch.

Even in the false dawn of Britpop, however, there was a sign of hope, even redemption. A blazing comet descending at the exact moment Britpop was ascending, a band crashing to earth in the grandest way possible. Its name was Dog Man Star.

There used to be a cliché that the correct answer to ‘Blur or Oasis?’ was ‘Pulp’, which however pretentious it sounds bore the mark of truth. If you answered ‘Suede’, the reaction was interesting. Eyebrows raised. You were suddenly… suspect, questionable. The word even sounded like a basement password leading to untold debaucheries. It carried a loucheness, the faint air of being disreputable, like wearing a green carnation or reading The Yellow Book during the Victorian Fin de siècle (the band inherited a queer literate Wildean quality from The Smiths, who were themselves, standing on a continuum), the suggestion of being a denizen of some orgiastic netherworld and donning a skin-suit of respectability for the daylight hours. There were worse ways to be or appear. It might even have felt like a badge of honour.

One of the more infuriating aspects of the class system is the fact that the ritualistic performance of authenticity, even when it is blatant stolen valour from the poor, is more highly prized and rewarded than actual authenticity. Though stylistically disparate, bands like Suede, Pulp, the Manics and so on came from working class backgrounds and shared a proud and voracious appetite for culture. They were shamelessly erudite, glamorous misfits and attracted similar followings. Their authenticity was expansive (in literary, political, even sexual ways) and went in a deliberate multitude of directions. It might lead you to Scott Walker or Albert Camus or Sylvia Plath or J.G. Ballard or whoever. And yet this curious expansive quality, always present in the self-educating side of working class culture incidentally, was seen as less real than a bunch of rugger buggers and finishing school girls caterwauling about drinking booze and doing lines in someone else’s accent.

Commentators have pointed to Suede as the beginning of Britpop, which is like blaming the defendant in a libel case for being sued or a victim of witchcraft for having a hex launched against them. The term would prove to be a dread millstone for them until Dog Man Star made a nonsense of the claims of paternity. Whoever owned this changeling, it was not theirs. In an interview with the author Adelle Stripe, Brett Anderson pointed out a crucial differentiation that separated Suede from the pack, “I was documenting Britain and they were celebrating Britain.” They had marked the beginning of a wave of genuine excitement and possibility, with three astonishing, brash and provocative singles (‘The Drowners’, ‘Metal Mickey’ and ‘Animal Nitrate’) and a lot of delightfully doe-eyed ’fuck me’ poses on magazine covers, all cut-glass cheekbones and fringes and incendiary cover lines asking for trouble. They hailed from the right side of glam (Bowie was undeniably a forefather) and while they had a swagger, as much as decadent goth-peacocks can, there was something very appealing in their disconnection from the braggadocio of earlier rock icons. They were as coy or even sub as they were seductive and bold, being sexually ambiguous at a time that badly badly needed it.

It was the fourth single though, ‘So Young’, that pointed the way ahead. An incredibly atmospheric nocturnal cityscape of a song. You didn’t need to see the video, as it was its own video. Impressionistic, unmistakably romantic, naïve even, in love with being young, where even the invitation of “let’s chase the dragon” sounds irresistible. The sinister magic wears off though. You end up chasing the original hit, and the innocence therein, but you can’t get it back, it’s gone forever, and eventually, if you keep going and you do, you might not even get yourself back.

The origin of ‘postlapsarian’, meaning to be post-romantic, is ‘after the fall’. It seems to fit Dog Man Star perfectly. At the time, it must have felt like a disaster. A terminal case of second album syndrome. The extraordinarily talented guitarist Bernard Butler had left in acrimonious circumstances before the album’s completion, after separate tour buses and recording sessions, private outbursts and theatrical public salvos. Much of these incidents seem understandable in retrospect, especially when throwing grief and substance abuse into the mix. In a wider sense, it’s unrealistic to expect band relationships to be a campfire jamboree. Artists are beautiful monsters, that’s the whole point of them. Yet the loss of such a crucial force so early feels tragic, the kind of change that can never be reversed, hence postlapsarian. Though in truth, in Dog Man Star we hear them mostly recording in freefall, with the ground an ominous rumour.

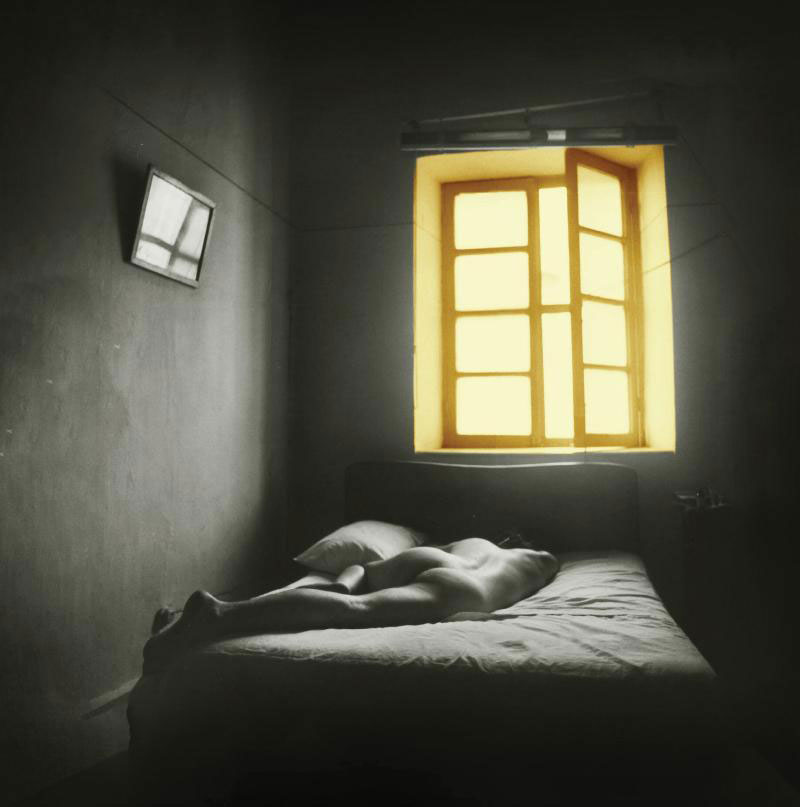

The postlapsarian condition is perfectly captured in the album’s cover. The image is ‘Sad Dreams On Cold Mornings’ from the feminist artist Joanne Leonard’s Dreams And Nightmares (1971). In the series, Leonard features romantic imagery glimpsed through the windows, reflecting on their unreality, and how far women fall when they reach for these false promises as she sees them, leaving them entrapped or abandoned. The enigma and androgyny of Suede’s first album cover (a Tee Corinne photograph from the book Stolen Glances) is repeated here but there’s a palpable sense of loss, even dejection.

How then does Dog Man Star feel not only like Suede’s finest album but the beginnings of a redemption of that entire period? It does so because it encapsulates the fall as few have before or since, the fracturing upon landing and then the reconstruction, the salvation from the fragments. It is a dark, cracked album and both qualities add to its power. The fact that the mixes feel wrong at times, the sense of it being both expertly sequenced as a voyage, neatly bookended, and yet incomplete, wanting and wanton, actually works in its favour. One form of the band is disintegrating, the next has not yet formed. That old line from Gramsci’s prison diaries springs to mind, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” What is terrible in politics is not necessarily terrible in art. Dog Man Star is an album that gives “a great variety of morbid symptoms” a good name. Perfection would have been a mistake. It feels like Kintsugi, the Japanese tradition whereby gold seams are used to join broken pieces of pottery, making them far more fascinating and attractive than just another pristine manufactured piece.

It’s a challenging listen for sure, from the off. Inspired by Buddhist chants in a Japanese temple, the drone of ‘Introducing The Band’ is designed to shake off the tentative. It sounds like apparitions walking through the Great Smog of 1952. Renowned as a hook-laden singles band, the song sets expectations that this album is an album. A journey. The first part of which is to swim through the swamp of the production that Butler loathed. Yet as diverting as the alternate versions included on the deluxe edition are – the more exposed, vaguely Doors-esque ‘Squidgy Bun’ version or Eno’s epic version, which sounds like it’s in search, and deserving, of a film – the final choice was correct and admirable in its contrariness. Inspired by Orwell’s line, from 1984, “If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever”, the track is as far from the cheery mockney pantomime of ‘Parklife’ as humanly possible. It’s dystopian, oppressive but not resigned.

The extended passage of Orwell’s is worth including as it hints at questions of power and dominance even sadistic pleasure that Suede were tuned in to: “There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always – do not forget this, Winston – always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless.” The lyrics of the song teeter on the razor’s edge of parody but the playful teasing of sexual roles and BDSM is compelling, and the drone acts as a guide, making the rock & roll/totalitarian analogies more Diamond Dogs than The Wall. Humans are never just political creatures but rather there are many other desires and impulses simultaneously at play; very much Suede’s kingdom back then.

Given that ‘Introducing’, admirably, was the sound of commercial suicide, ‘We Are The Pigs’ was an invigorating assurance that the band had not lost or abandoned their talent for resplendently grubby choruses and flamboyant statements. The vision remained dystopian though. Suede always dealt in urban imagery – flyovers and laudanum, cursed love affairs and sunsets viewed from sinking tower blocks. The romance has ebbed here a little, the menace increased, though it’s delivered with glee, somewhere between Lord Of The Flies and ‘Come To Daddy’. It’s a hymn to anarchy and destruction but the nuclear references, a recurring echo through Anderson’s lyrics, remind us that what are bands of marauding pig-faced rioters compared to growing up in supposedly sane societies where the apocalypse was only a four-minute warning away?

It would be wrong to say Dog Man Star is bereft of romance. ‘Heroine’ opens with Lord Byron’s “She walks in beauty, like the night…” Yet the romance is never simple, and never was for a band skilled in portraying both the night before and the morning after. The song plays on the similarities of ‘heroine’ and ‘heroin’ (there are at least three different types of eye rolling throughout), and the subject is really isolation and the replacement of love with the pathos of pornography, a development that has since consumed the Western world. Byron is the perfect foil for this twist, given if there’s a real-life embodiment of Milton’s anti-hero Satan, it’s this particular Romantic poet, an infamous figure cast out for his transgressions.

Another change, compared to its predecessor, is that the finest moments on Dog Man Star are its quietest and most delicate. There’s a newfound confidence not to strut but to let the songs exist as their own little worlds. This is evident in ‘Daddy’s Speeding’, a warped hymn to Hollywood and James Dean, killed driving his Porsche Spyder, nicknamed ‘Little Bastard’, along Route 446. Dean is a fitting character to focus on. Sexually charged and ambiguous stories swirl around him, a free but tormented figure in a corrupted time. It’s an unusual song combining show tune theatricality and dreamy-then-phased vocals (prompted by Lennon’s sleepy/acid period) with ghostly chamber music, never quite settling, brilliantly so, climaxing with a whirling wall of feedback, a crash and the roll of a wheel. Beginning with what sounds like a drunken saxophonist falling down a lift shaft, ‘This Hollywood Life’ is song that finds its way to the corruption behind the mask of glamour, where the monsters are not aberrations, dreams are bait, and celluloid faith is no less venal than any other. “Forget it, Jake. It’s Hollywood.”

Politics do play a part throughout, but they are explored where they truly manifest and matter, which is in people’s lives rather than polemic – race in the relationship of ‘Black And Blue’, class and empire in ‘The Power’. Growing up in poverty shadows much of Suede’s work but it’s always poetic, resistive and idiosyncratic, as hard as it gets, because that’s what it’s actually like (Anderson’s first excellent book Coal Black Mornings is especially strong on this) rather than the caricature it’s depicted as from outside. Sexuality is another major theme and attraction of the group. While hardly Coil, Queercore or Paris Is Burning, Suede’s shapeshifting sexual attractions, identities and gender roles was welcome at a time of ‘acceptable’ mainstream prejudice towards LGBTQ people and worse (Section 28, the unsolved murders of Michael Boothe and others, the moral panic of AIDS, the poisoned soil that led to David Copeland’s bombing of the Admiral Duncan among other atrocities, and so on). The fragile and thus inflated masculinity revived by Britpop, encouraged by lads’ magazines, was one of the most depressing spectacles of the era and had real impacts upon peoples’ lives, at a time when so-called ‘gay-bashing’ was not uncommon and intolerance was rife. The freedom exalted in so many Britpop anthems could be a deceptively exclusive thing.

The soul of the album is ‘The Wild Ones’. It feels related to ‘Stay Together’, a magnificent stand-alone single of the time that serves perhaps as Bernard Butler’s magnum opus. Where ‘Stay Together’ is a Busby Berkely production, ‘The Wild Ones’ benefits from its relative intimacy, even though the vocals were aiming for Jacques Brel territory. It’s romantic but it’s a wise even scarred kind of romance. And it’s worth noting that Anderson wrote the album’s lyrics while living in Highgate, a stone’s throw from the place where the most mysterious of the Romantics, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, went to overcome his opium addiction and ended his days. No longer are they intoxicated by being young and fabulous, instead ‘The Wild Ones’ is a desperate plea for a love not to leave. ‘The 2 Of Us’ continues this mood of the sweetest melancholy, and can be read, regardless of their wishes, as a broken love song between Anderson and Butler. Every choice in life, it suggests, involves the negation of another path, lost possibilities, and there is no avoiding this one chooses the false harbour of safety and stagnation. Fucking up rarely sounded so serene.

While the extended roaming outro of ‘The Wild Ones’ has a darkly psychedelic mood, reminiscent of Jane’s Addiction or The Cure, ‘The Asphalt World’ is the best example of their ability to create and sustain a soundscape. It’s majestic but never loses a whispery closeness. And, as a strong contender for their finest moment, it’s amazing that while the band and album seemed to be falling apart, all the disintegrating pieces just happened to land into shapes that were mountainous, temple-like.

Collapse is inadvisable. There’s every chance Dog Man Star was simply a freak of nature. Never let a resident genius, a Marr or Butler or whoever, leave. Few bands survive such a loss. Or at least let him or her stay to see what their vision is. And yet, this anomaly exists. Adversity is not something that should be courted, there are many who unjustly cannot escape it, but that’s not to say the friction does not have results. The light and heat of atmospheric re-entry. Blur ascended a level when the wheels began to come off – the trilogy on 13 (‘Caramel’, ‘Trimm Trabb’ and ‘No Distance Left To Run’) marking new heights and depths, both being intrinsically connected. Even Oasis made their deepest, most interesting third of an album with the beleaguered Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants, peaking with ‘Gas Panic!’, before retreating back into the sheeeeiiiiiiiite. Dog Man Star accelerates past both. In which direction is superlative. The idea of up and down is nonsense in space where everything is relative. You can soar downwards or fall upwards. Everywhere is exiting heaven. It’s the energy and mass that matters and what it leaves behind when it finally crash-lands. Satan, patron saint of jaded romantics, is always falling through the skies. And his message, as dictated by a blind writer centuries ago is still as true as ever, “Better to reign in Hell than to serve in Heaven.” Next year, when tired old relics are once more dusted off in stadia at great cost and to ever-diminishing effect, remember the treasures to be found in the wreckage elsewhere, not just back then but right now, all around us. If Suede created this at a hopeless time, there’s always signs of hope, always something gloriously plummeting to earth.