Three Album Run is a tQ series where we explore the best unbroken run of LPs in different genres. This month it’s twentieth century heavy metal but if you want to suggest a genre for a future essay please email John@theQuietus.com under the heading Three Album Run. The full rules are at the foot of this feature.

In the spring of 1998, when I was sixteen years old, I rented a bike for the day during a family holiday on the North Devon coast. I cycled on the Tarka Trail from the village of Braunton to the town of Bideford, skirting the River Taw estuary – a 28-mile round trip.

I took my Sony Discman and two CDs. The first was the self-titled debut by nu-metallers Sevendust, released the year before. The second was Seasons In The Abyss by Slayer, which I had recently bought. I listened to them both a few times on the way there and back. The crunch and low-end heft of Sevendust was already a favourite. But I ended the journey gripped in the jaws of Seasons In The Abyss.

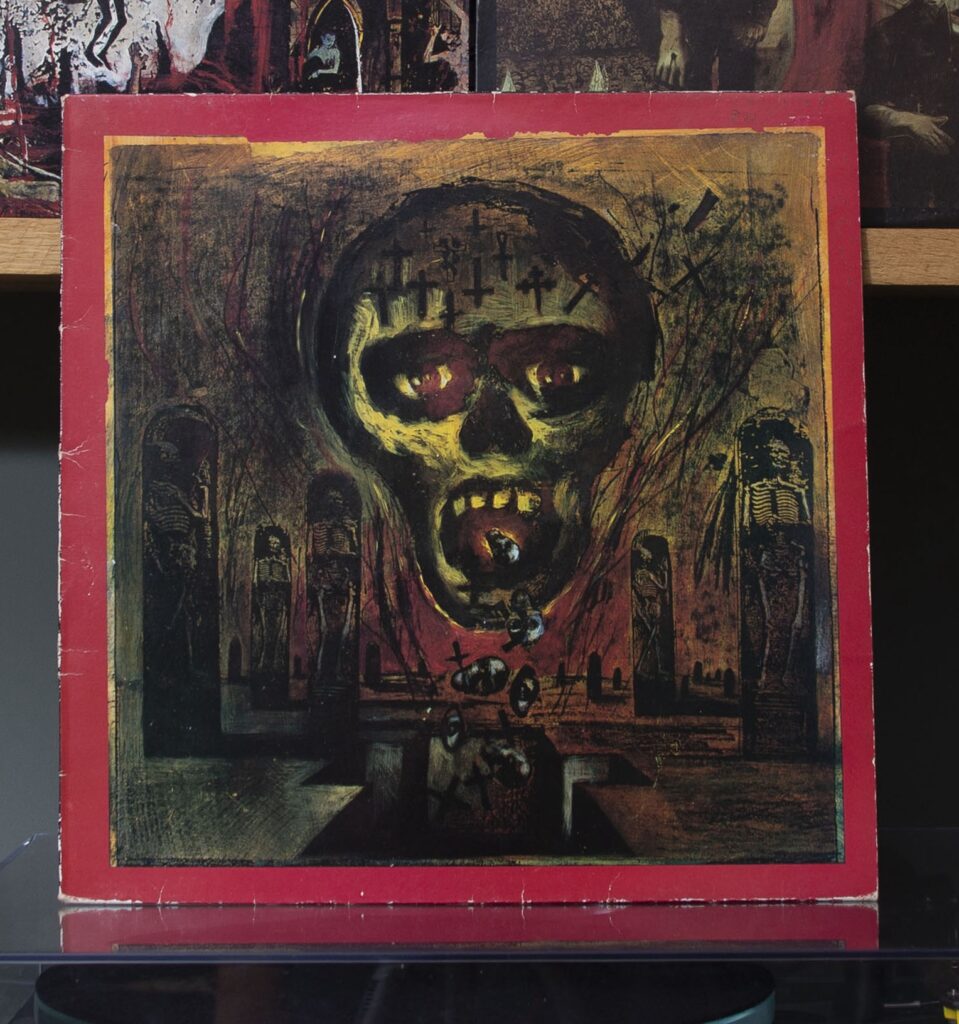

It was apposite to listen to these albums back to back. Seasons In The Abyss, released in 1990, is the final album in a three-album run by Slayer that gave birth to the much heavier metal of the nineties. They pulled back the skin of heavy metal’s artifice to reveal the raw-blooded intensity underneath.

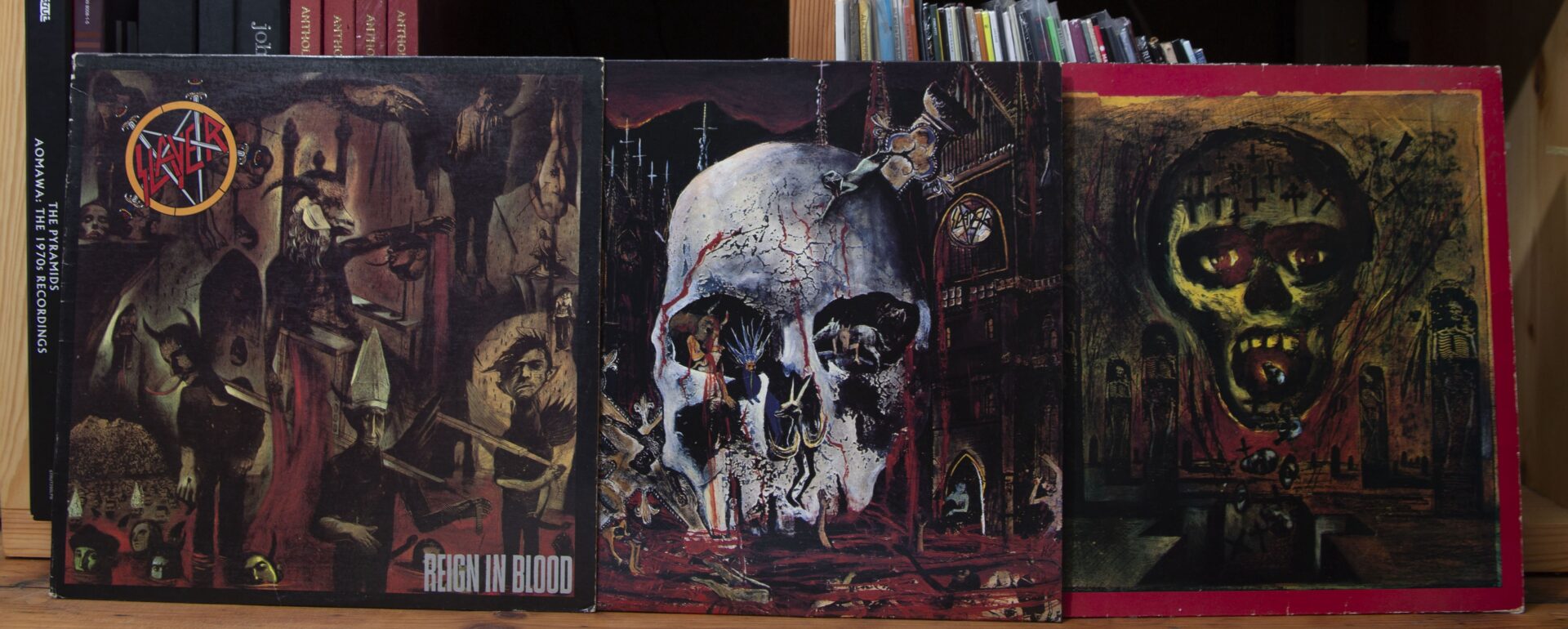

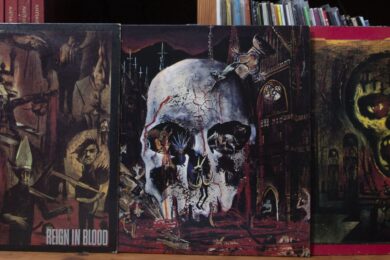

With Reign In Blood (1986), South Of Heaven (1988) and Seasons, Slayer created a shadow world – a dark mirror to reflect the most horrifying elements of humanity. This three-album run – which functions as a diabolic trilogy though it wasn’t designed as one – ripped heavy metal out of its moorings and threw it into the fire. They transformed the genre with a musical radicalism and lyrical perspective from which there was no going back. The brutal innovations that followed – at the fringes of heavy metal and at its centre – were built upon the foundations of these albums. They constitute a revolution in twentieth-century metal, itself a revolutionary form, that makes them the most important sequence in the genre.

Seasons In The Abyss is held up by three tentpole songs: ‘War Ensemble’ at the beginning, ‘Dead Skin Mask’ in the middle, and the title track at the end. The first bars of ‘War Ensemble’ capture everything important about Slayer. There’s the drum stroke and clutched cymbal that launches the warp-speed tremolo-picked guitars, and three further drum hits that punctuate the turnaround of the opening riff. On the second pass of that impossibly fast riff, the crowd of notes in its tail barely fit within the meter. Guitarist Jeff Hanneman wrote the song. As Slayer’s other guitarist Kerry King said to author D.X. Ferris of Hanneman’s skill: “Jeff plays notes that are just angry to be together.” Following that, there’s Dave Lombardo’s almost disorderly drumfill and the thrilling, locomotive effect of Slayer at full tilt. Thirty-five years later, ‘War Ensemble’ remains a shock.

The song begins almost exactly like ‘Angel Of Death’ from Reign In Blood, a record of such concision and ferocity that Slayer infamously shaved four minutes off its recording time from instrumental cassette demo to final studio version. Why Slayer’s three-album run doesn’t begin with 1984’s Hell Awaits is because that album has two fewer tracks than Reign In Blood but is eight minutes longer. What outstripped Hell Awaits was the band’s ruthlessness in self-editing. Slayer’s focus and incisiveness peaked with Reign and blazed on for two further albums.

What we’re hearing in the first riff of ‘War Ensemble’, and the second-phase breakdown riff in ‘Angel Of Death’, is a new form of chromatic catholicity in heavy metal. Slayer partly dispensed with the pentatonic character of their earlier albums and embraced modes of songwriting and key changes that owed more to free jazz. Hanneman and King’s squalling guitar solos, deployed in ferocious, strafing attacks, were blasts of anti-music. They created a new language for metal in their dissonance and brinkmanship, akin to speaking in tongues and mocking the blues-based hard-rock order.

Almost as startling as what emerged from the furnace of Reign’s writing sessions was the collateral reinvention of other, contiguous heavy music genres. Slayer changed metal by infusing thrash with the speediest hardcore punk, and then, in turn, changed hardcore forever. South Of Heaven saw the band slow to a mid-paced stomp on ‘Live Undead’, ‘Behind The Crooked Cross’ and ‘Mandatory Suicide’. After the devil-dancing instrumental break of ‘Ghosts Of War’ from that album, and the rudely sublime melodic revelation of Hanneman’s second solo, Slayer hits a corkscrewing breakdown that hardcore stalwarts Terror lifted wholeheartedly on ‘Spit My Rage’ from 2004’s One For The Underdogs. I went to see Terror support Knocked Loose a few years ago. I was unfamiliar with them before that night, but as soon as that breakdown hit, it was as if Slayer had been summoned into the room to rip the crowd apart.

Slayer were about distillation, rubbing against metal’s tendency for overabundance. These albums were all co-produced with the band by a young Rick Rubin, as well as engineered and mixed by Andy Wallace (who also took a production credit for Seasons). Slayer’s greatest three-album run is also Rubin’s as a producer for a single artist. The three albums have an arid production (hell is a dry place), with selective reverb on the drums, close vocals and a serrating guitar tone. Slayer sounded heavier live – but they didn’t sound as Slayer-ish.

“Distilling a work to get it as close to its essence as possible is a useful and informative practice,” Rubin explains in his 2023 book, The Creative Act. “Notice how many pieces you can remove before the work you’re making ceases to be the work you’re making.”

What Rubin removed from Slayer was the booming midrange frequencies that would have muddied the sound. Rubin discussed this at length with Wallace. Together they wanted it to feel like you were in a boxing ring with the band.

“I played him [Wallace] a Metallica record as an example of what I thought was wrong,” Rubin recently told YouTuber Rick Beato. “And I said, ‘Would it be possible to record in such a way that it was hard-sounding but everything was short, because it’s fast and we want there to be this?’ I didn’t want it to be a blur of bass; I wanted it to be a pulse.”

Slayer broke it off with Wallace when he mixed Sepultura’s Arise album, released in 1991. Wallace then went on to produce Sepultura’s follow-up, 1993’s Chaos A.D., which encapsulates the sonic legacy bequeathed by Slayer. It’s a stripped-back, pummelling album infused with bare-bones intensity. The following year, Wallace also produced Jeff Buckley’s Grace, firmly imprinting his infernal mark on nineties music.

Now I’ve mentioned Metallica, why isn’t this piece about them? Despite their unquestionable importance in metal’s history, and preeminence in the Bay Area thrash scene of the 1980s, I don’t think they have three albums in sequence which cohere as well as this trio by Slayer. Neither Kill ‘Em All nor …And Justice For All are as good as Ride The Lightning and Master Of Puppets, the two albums which need to belong in any proposed run. If people are shocked by this idea then it is received wisdom that has only really solidified with time after Metallica became one of the biggest selling bands in the world; back when when it was released, Kerrang! called Reign In Blood “far superior” to Master Of Puppets.

Over the course of these three albums, Slayer developed a means of saying the same things differently. That is what they share with the ethos of AC/DC and Motörhead. ‘Spirit In Black’ from Seasons sounds like it’s quoting a passage from Reign In Blood with the furious acceleration in the second half. Slayer were both radical and sounded reliably like themselves.

What about other contenders? The main problem with Black Sabbath is where do you start and end the run within their first six albums? Also, though they gave birth to the genre, it was yet to have grown into itself, and Sabbath aren’t actually as metal as Slayer. Judas Priest, beloved of Slayer’s members as they are, simply don’t have a viable trilogy which isn’t spoiled somewhere. The band that troubles me the most in this equation is Iron Maiden, specifically their run from The Number Of The Beast to Powerslave via Piece Of Mind. But it’s in the nature of their worldview which makes that run inferior to Slayer’s. Bruce Dickinson’s “theatre of the mind” and the inherent storytelling of Maiden’s songs – holding the audience at arm’s length – falls foul of Slayer’s all-consuming Satanic Realism.

Slayer singer/bassist Tom Araya pioneered a way of articulating drill-sergeant-spewing, documentary-like lyrics. Araya is witness, judge, jury and executioner. Even when their songwriting is lurid and borderline camp, such as on ‘Dead Skin Mask’, or the proto-death metal lyrical fodder of ‘Piece By Piece’, Araya’s sharp enunciation, pitch-black humour and sheer relish brings you into their songs.

Slayer also uses the rhetorical device of prosopopoeia – personifying an absent person or abstract concept – to truly inhabit the material. It’s what landed them in trouble for beginning ‘Angel Of Death’ with a couplet that was on its first line declamatory, and with its second line switched to the perspective of sadistic SS physician Josef Mengele: “Auschwitz, the meaning of pain/The way that I want you to die”. Def Jam’s parent label CBS refused to distribute the album because of ‘Angel Of Death’ (Geffen eventually did the honours in the US).

“They want the cutting edge. But they’re afraid to get cut,” spat Rubin.

Time and again, whether it’s the “convicted witch” of ‘Reborn’, the aborted fetus of ‘Silent Scream’, or representing the spirit of war itself on ‘War Ensemble’ (“The final swing is not a drill/It’s how many people I can kill”), Araya is our dispassionate guide to the horrors in which we are all implicated. By extension, at some deeper (or maybe surface) level, we enjoy their depiction.

This is the crucial point about Slayer: their music is not cathartic. These three albums are a harrowing journey into the darkness; we are plunged into it and they hold us there. The feral devotion that listeners give to Slayer or “fuckin’ Slayer” or “SLAYAARRGGGH”, depending on how big a fan you are, recognizes that they will take us places we are too unwilling or afraid to go to by ourselves.

As Orlando Reade notes in his book about the legacy of Paradise Lost, What In Me Is Dark, John Milton thought that untested virtue was “excrementall whitenesse”. Slayer will test your virtue to its limits, and it’s more revitalising if you don’t shy away. William Blake said Milton was of the devil’s party without knowing it, but first-time listeners know when they’ve been ensnared by Slayer’s revolutionary energy.

When the band first travelled to the Bay Area from their base in Los Angeles in 1984, they played the Keystone venue in Berkeley. Back then, they wore eyeliner onstage. But after being reprimanded by the local thrashers that this wasn’t de rigeur, they left it off the following night at the scene’s epicentre, Ruthie’s Inn. Slayer, already a vicious anomaly within the thrash movement, were being shown the courage of their convictions by their peers: keep it real. What they were expressing and how they were expressing it didn’t need to be dressed up or dissembling.

This extended to the band’s collaborators. The artist Larry Carroll initially confounded the band with his cover painting for Reign In Blood, which landed somewhere between the hellish chaos of Hieronymus Bosch and brutal beauty of Anselm Kiefer. His artwork for the trilogy (and later 2006’s Christ Illusion) overhauled heavy metal visual tropes. Carroll’s art is so synonymous with the band that he only ever worked with Slayer in the genre.

The blood that rains down from a lacerated sky at the conclusion of Reign is the blood of angels infusing satan with power. At the opening of South Of Heaven – Slayer’s greatest melodic construction – we are in the welter of “Chaos rampant,/ An age of distrust”, where we remain for that album and its successor, until the final feedback of ‘Seasons in the Abyss’ fades. This Slayer trilogy begins with the word “Auschwitz” and ends with the word “insane”. It represents nothing less than the legacy of the twentieth century, as the band blazes into the final decade and sets the pace for the new millennium.

Having given birth to the realism and naked aggression of nineties (and later 21st-century) metal, Slayer toiled to adapt to a world they had created as the decade progressed. The band mutated, and were overtaken by others who had paid close attention to their lessons in violence. But even in 1998 they were a force, co-headlining a world tour with Sepultura supported by new Rubin protégés, System Of A Down. In recent years, they have grown to staggering proportions in the history of the genre. Particularly in the past 12 months, as they have re-emerged to headline festivals five years post mortem and their official final world tour that ended in 2019.

When Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive was released, I went to a screening with an introduction by the director. He said he had only two stipulations for his films – that they be no longer than ninety minutes and “extremely violent”. Listening to Reign In Blood, South Of Heaven and Seasons In The Abyss in a row will take you a little longer than that – 108 minutes, give or take. The dreadful realisation of inhabiting the world Slayer created on these albums is not how well they capture the horrors of our past. The vitality of the trilogy as art is how they describe a hell that goes on and on, and illuminates the darkness within us all.

Sign up to tQ’s free weekly Digest Newsletter for future 3LP features and much more

Three Album Run: Rules

- No live albums, no comps, no covers LPs, no collab records, no anthologies etc.

- Albums listed by year they were released not recorded

- No name changes unless name changing is part of the aesthetic. I.e. including albums by Tubeway Army and Gary Numan in the same run is not OK, but any permutation of the Osees as a three album run would be OK

- Album run has to start after 1970

- Ignore the band or artist’s feelings on what genre they are. The Cure are either goth, post punk or alternative rock. Sorry, The Cure!

- Even if we find the genre slightly spurious we’ll rely on main/leading genres provided by Wiki, All Music and Discogs. I.e. if Wiki say Roxy Music are “Art Rock” or “Glam Rock” then one of those two genres is what we’ll stick with