It looks like a sea of beans out there. White, greasy and bulbous – haricot, perhaps, or borlotti, each flabby shaved head bobbing about in the sweaty, man-stink morass of a mosh pit that’s populated and policed by the most far right Nazi street thugs that the North East of England is capable of producing.

It’s 1992, at the Riverside in Newcastle, and our fourteen-year-old Sunderland-supporting drummer Michael has told a derogatory joke about Newcastle United, a bold and ultimately suicidal move in a region where football is religion.

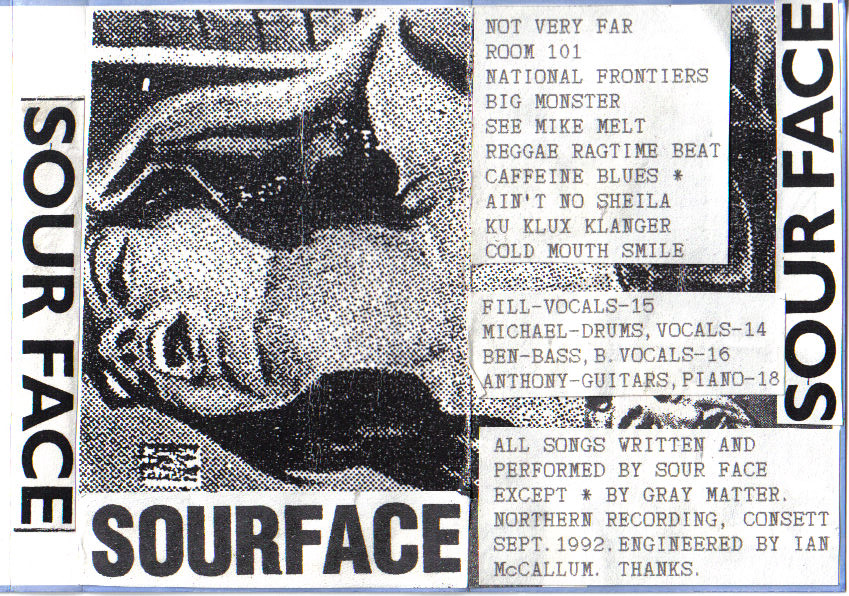

We are Sour Face and we have come for your children.

The Riverside has hosted shows by Beastie Boys, The Stone Roses, Henry Rollins and Red Hot Chili Peppers. Nirvana played their first overseas gig here opening for Tad and in 1994 it will be the venue whose crowd will feel the need to leap on-stage to lamp Noel Gallagher in the chops and literally run Oasis out of town.

But for now it is hosting a flailing Sham 69, a band whose last charting single was released the month that our drummer Michael was born, and who are now reduced to playing Doors covers and Oi! classics (and the extended, prog-flecked twelve-inch version of ‘Borstal Breakout’ is a classic) while suffering the ignominy of sharing a bill with four pre-pubescent (again literally in the case of our thirteen-year-old singer Fill, whose voice had not yet broken) virgins from the suburbs.

Sham 69, lest we forget, originally split in 1980 after releasing an album described by singer Jimmy Pursey as “shit”, and seeing their shows marred by the violence of the same right-wing skins who co-opted Pursey’s “for the kids” street level rhetoric into their own twisted ideology. But now it was the 1990s, a new decade entirely, yet out in the northern provinces little had changed in the interim as the stubbled hair of three hundred saggy skinheads stood on end when confronted with the mighty ‘Face.

All bands are idiots. Having spent twenty-five years trailing them as a music journalist – from the height of Britpop through to the COVID pandemic – I do not make this judgement flippantly.

In fact, I knew that all bands are idiots long before I talked my way into the position of staff writer at Melody Maker literally the day after I sat my last university exam, long before I was bouncing around Hollywood squeezing coherent sentences out of two-bit, multimillion selling nu metal bands for Kerrang!, and way before I spent five years co-running an independent record label in the 2000s, at the very same moment that physical sales began to plummet and the commercial end of the music industry fixated on a few safe bets.

I know all bands are idiots because from the age of fourteen to sixteen I played in one.

Sour Face were a punk band literally born out of my friend and our first drummer Kevin’s garage in a semi-detached house on an estate a few miles out of Durham City. We started out, as all bands do, playing metal covers, and with a name – Diamond Child – a logo, and a hand-drawn poster (for ‘The Golden Ski Jacket’ tour) in place. No gigs or songs to speak of, though. Within four months we experienced something of a collective epiphany when it became apparent that metal can actually be quite technical, and in fact hardcore punk was a genre better suited for disguising inability. We changed our name to Sour Face, a reference to a description of Richard III, and talked our way into a debut gig in March 1991.

Durham had a strong hardcore scene thanks to a complete lack of musical infrastructure and a couple of highly motivated straight-edge skateboarders who, inspired by Minor Threat, Youth Of Today, Slapshot and Negative Approach, formed their own bands in order to open up for whoever they could persuade to stray from the beaten touring track to play our local youth clubs.

How easy it is today to forget that pre-internet, the bands who meant the most to us teenagers were those who were right in front of us: those local acts who we could see for £2 in venues without alcohol licences – bands like Steadfast who, having released an actual seven-inch single, might as well have been The Beatles. When key American underground bands such as Born Against and Quicksand came through our town, me and my pals wanted in on the action too, and at the dawn of 1991 formed Sour Face.

We were: aforementioned first drummer Kevin (mustachioed at fourteen, I once saw him get punched by older hard lads for having long hair, and then disarm them by laughing openly in their faces); guitarist Davey (a virtuoso pianist and still my best friend today), singer Fill (a precocious thirteen-year-old combination of Johnny Rotten and Jay from The Inbetweeners) and on bass, a twitchy, five foot tall, bespectacled golem with a mullet, who couldn’t play a note but did have access to amplifiers thanks to his older brother being in the North East’s premier shoegaze band and sometime tour mates of My Bloody Valentine, The Lavender Faction.

That golem was me.

Our first show was a fifteen-minute, early afternoon set opening for eleven other bands on a “pay or play” bill. We rattled through our seven songs at a frantic whiplash pace, with an inability that was disrespectful to the entire concept of music, but that nevertheless managed to upstage the various over-serious thrash, death and hair metal bands who followed. We swiftly recorded a demo tape, which we copied on to old red or green cassettes that had previously held computer games for an early BBC Microcomputer. We couldn’t shift them quick enough and began to get reviews.

Our third show was supporting a Californian punk band called NOFX, who we found wandering lost in their minivan, and whose drummer Erik Sandin was evidently discovering that heroin was not so freely available in Durham City Rowing Club as it was in the squats and crash pads of San Francisco and LA. NOFX could not only write songs but they could sing harmonies too and they blazed a trail playing non-venues that their pals Green Day would follow six months behind them (eight million album sales later, NOFX play their final shows in late 2024). Soon afterwards we ourselves were supported by a new band born out of the ashes of Steadfast, who were now called Voorhees and whose snarling musical violence would define them as one of the key UK hardcore bands of the 1990s.

But because all bands are idiots and twelve months is a long time when you’re a school kid, Sour Face couldn’t hold a steady line-up for long. Schisms appear, cliques develop and new splinter groups form. Our drummer Kevin departed to be replaced by thirteen-year-old wunderkind Michael from Spennymoor, who impressed us all by dropping some mescaline one night and running around red-faced for several hours. What even was mescaline? Michael also had an encyclopaedic knowledge of Japanese avant-garde noise, could drum like the devil himself and we were already pals with his brother Stephen, who sang in various death and doom metal bands such as Morstice and Blessed Realm. Davey departed when his parents banned him for playing a show the night before he and I sat a GCSE exam. We ruthlessly replaced him with our friend Lukey, a fan of The Fall who wore a fishing gilet onstage, whose pockets were stuffed with Gaviscon, and in whose garden shed we brewed the cloudy gut-rot homebrew that fuelled our performances.

For two years we gigged, argued, scraped together finances, recorded and released demo tapes, and gained a certain level of notoriety across the North for being unrelenting in our ability to wind up both fellow bands and punters alike. But when you’re fourteen and grown men with cars, jobs and children are donning the studded wristbands and corpse paint, it’s hard not to point and laugh. Which we did, often. Our songs were nonsense blasts about testicular injuries, meeting Rolf Harris in Paris, obesity and racist twats, and we shared stages with dozens of bands such as Hellbastard, Lawnmower Deth and local heroes China Drum. We played with grebo bands, black metallers, bequiffed garage punks, quirky indie groups. We got thrown out for being drunk in a Catholic school which had inexplicably booked us to headline an end-of-term show, without having heard us. We opened beer cans while pious straight-edge bands preached purity. We took mushrooms before playing with a bunch of anarcho bands on an Animal Liberation Front benefit show, before carrying all our gear for five miles across Newcastle at kicking out time. While still tripping.

Yet, at the same time, in those two years I learnt more transferable skills than I did from the GCSEs that I took during the same period, and not all of them involved getting as high as possible on a minuscule budget. At fifteen I learnt how to deal with adults by ringing venue promoters. I had a Filofax (it’s like a mobile phone without a signal) stuffed with the numbers of other punk bands, labels, promotors, fanzines, local journalists and anyone who could help the cause. I got us interviewed on local radio, raised finance from community grants for studio time, achieved some degree of press coverage, played close to forty shows and managed to avoid any of us being arrested and/or receiving the severe kickings that we – piss-takers to a man – undoubtedly warranted (all of that happened the summer after the band split, when I was battered and robbed in Durham one week, and then arrested in Leicester Square the next).

And now here we are, in the glamourous Riverside venue, which has its own TV show on Tyne Tees television and whose backstage fridge contains nothing except one frozen, cigar-like, human turd.

As a score of skins clamber on stage and turn our heads into waffles, I attempt to defuse the situation by announcing from behind a bass the same weight and size as me that our next song is “about the Ku Klux Klan” (topical). It’s met with cheers of approval, so I meekly add “No, no – it’s against them.”

The mood quickly sours further as the ‘seig heils’ start and the venue’s security begin to look scared for the safety of the four children who have had to be granted a special licence from the council to perform in such adult venues. Reasoning that punks of all political persuasions loved the Sex Pistols, we revert to our trump card – a double-time cover version of ‘God Save The Queen’, a song that for the league of bald-headed borlottis recalls happier, simpler times of endless summers, jumpers for goalposts and hate crime. Miraculously it works and the borlottis show their appreciation by fully invading the stage and enveloping us entirely. We are actually much less scared than the venue staff are as our instruments disappear beneath an intensely homoerotic pile of bleached jeans, red braces and bomber jackets. There’s always been a fine visual line between love and hate in the codified rituals of the punk/hardcore/skinhead crowd, and tonight we tread it. We win them over though – the naivete and confidence of youth is a wonderful weapon – and having faced down a frothing crowd of rabid fash, we’re exhilarated as a concerned Jimmy Pursey looks on. “Facken ‘ell, lads,” he says as we pile into the dressing room.

Sour Face soldier on until we don’t. We last for the entirety of 1991 and 1992 – the same amount of time as the Sex Pistols. It’s a two-year period that effectively sees all that we have grown up loving go overground thanks to the success of Nirvana, the only contemporary band (apart perhaps from Fugazi on a much smaller scale) who all the various indie, punk, goth and hardcore kids equally – and rightly – love. We split, as all bands do, under a cloud of rancour and resentment, the origins of which I can no longer recall.

The only regret is that we never released a seven-inch single – only cassettes. How could we? We had no money, no patronage, no local record labels, no wheels. Only paper rounds and terrible attitudes.

And now as I write this today, at the age of forty-eight, the internet tells me that after Sour Face split, three of us formed another band called Bagpuss, who played three gigs before dissolving. I have no recollection of that band or those gigs, though that doesn’t mean they didn’t happen; I’m often reminded of things I have said and done and places I have been that I have little recollection of (The Gambia, Las Vegas or Buckley, for example).

But what I do know is where the former members of Sour Face are today: first drummer Kevin played in several bands before moving to Australia and publishing an acclaimed book about Lookout! Records. Second drummer Michael played in many better bands, toured the US when he was sixteen, released records over three decades and curated an impressive archive of avant-garde music. In 2023 while visiting a cashpoint in Middlesborough he was stabbed in the head with a screwdriver by two teenagers and has experienced “life-changing injuries”. His attackers got heavy prison sentences; at the time of writing, he has lost the ability to drum. Michael’s metal vocalist Stephen transitioned, and is now Kat, a well-known and well-liked face on the international metal underground, and currently fronting Thronehammer. Guitarist Davey suffered some health problems recently but is on the path to recovery; he teaches music and currently plays in psychedelic folk band The Shining Levels, who recorded a soundtrack album for my novel The Gallows Pole and one to accompany Booker Prize-winning writer Pat Barker’s novel The Silence Of The Girls. We chat most days.

Second guitarist Lukey works in the local council office, as he has done for three decades. We’re also still friends. He remains much a Fall fan, and all that that entails. After not seeing him for twenty years, singer Fill (who once had ‘SKINHEAD’ tattooed on his noggin long after the Sham 69 debacle) messaged me one night shortly before Shane Meadows’ BBC adaptation of The Gallows Pole aired to tell me I “always was a wanker and a pretentious cunt”.

And me? I’m still here, a wanker and a pretentious cunt still doing the very same things I did at fourteen: listening to music, writing stories and avoiding anything approaching the responsibilities of real adult life, while still loosely adhering to the broad ethos of “punk”: never waiting for permission, and never allowing something as trivial as inability to hinder progress.

Sour Face were obnoxious people making obnoxious music. But at fifteen, we were also grafters, hungry to make an impact.

I wouldn’t have it any other way.

Benjamin Myers’ recent novel Cuddy won the Goldsmiths Prize, the Winston Graham Prize and is shortlisted for the Ondaatje Prize. His new novel Rare Singles is published in August 2024 by Bloomsbury. The adaptation of his novel The Gallows Pole is on the BBC iPlayer now