Wikimedia Commons

Royal Academy, London, 17 September 1997. Milling through the packed crowd in this most exclusive of exhibition private views, where Salman Rushdie is close to bumping into Jarvis Cocker, is an incongruous figure: rakish, unshaven, unkempt hair, dirty crumpled shirt, trousers held up with string instead of a belt, and ‘shoes’ held together with industrial tape. How, our fellow liggers must have been thinking, did this vagrant ever get past security?

It was in fact Gavin Turk, one of the artists in the show being celebrated, whose waxwork of himself as ‘My Way’ era Sid Vicious was among just over a hundred works that would be revealed to an eager public the following day.

Anarchy In The RA? Turk later commented that he was making a statement about the kind of people who are excluded from the world of high art. And in Britain at least it doesn’t come much higher than the Academy, the UK’s most august, establishment arts organisation. But the art in this exhibition, snazzily titled ‘Sensation’, was a marked departure from the institution’s usual fare – the display a culmination of a frenzied period of collecting by just one individual, former advertising executive Charles Saatchi.

As Saatchi wheeled his indiscriminate shopping trolley in the early 90s through makeshift gallery spaces in the areas of London no Chelsea resident would have ever considered go-to destinations – Oval, Deptford, Rotherhithe – his profligate spending would create a movement in his own God-like wake which, with the first show of his purchases in his pristine St John’s Wood Gallery in 1992, would be defined by its title: ‘Young British Artists’.

Five years later, the Royal Academy’s PR spin was promoting ‘Sensation’ as a landmark revolution in its history – the young upstarts with their preserved sharks, bad language, erect penis mannequins and disregard for conventional aesthetics, had entered, squatter-like, into the Corinthian columned gallery spaces that once housed Turner, Constable, Stubbs. Three serving Academicians felt compelled to resign, perhaps fearing the RA turning into a gilded palace of the abject and disgusting.

There was much that was silly about the hype surrounding the exhibition, not least the rather suspect message that these were artists who had largely come from the working class and were now being honoured by their presence in the RA’s chambers off London’s Piccadilly. What was significant, with the benefit of a quarter of a century, was something beyond the art. ‘Sensation’ was a high watermark of a year – 1997 – in which Britain incrementally became a nation in thrall to all things sensational, shedding much of its sense of reason in favour of bravado, dramatic self-congratulation, and (in one major case) melodramatic self-pity.

We’d been here before of course. 1997 was the twentieth anniversary of both the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save The Queen’. It was the thirtieth anniversary of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s and the media phenomenon of Swinging London. The time was ripe for a revival of that hoary old belief that the anti-Establishment was becoming the New Establishment, while putting the ‘Great’ back into our country’s identity.

First off, in February, Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine, pouting on Union Jack pillows, alongside the strapline ‘London Swings Again’. The article inside, though written in an obviously ironic style (one hopes), certainly set the tone for British braggadocio in the months to follow.

"From Soho to Notting Hill, from Camberwell to Camden Town, the capital city of Dear Old Blighty pulses anew with the good vibrations of an epic-scale youthquake! Parliament is undergoing a youthquake of its own! Say hello to shirt-sleeved, smiling Tony Blair, the leader of the ascendant Labour Party. The Right Honourable Tony is just 43 years old and has an outlook to match."

Within weeks of Vanity Fair’s publication, Blair had won a landslide general election – the Sensation(al) People’s PM. He proudly claimed his government would stand for "Old British values but with a new British confidence". His appointed Secretary of State for Culture, Chris Smith, would later give the ‘Sensation’ exhibition his seal of approval, praising it for its dynamic representation of "Britain with attitude". And in the New Labour equivalent of Harold Wilson bestowing MBEs on The Beatles, Blair of course famously welcomed Noel Gallagher to a reception at Downing Street to mark the country’s cultural high.

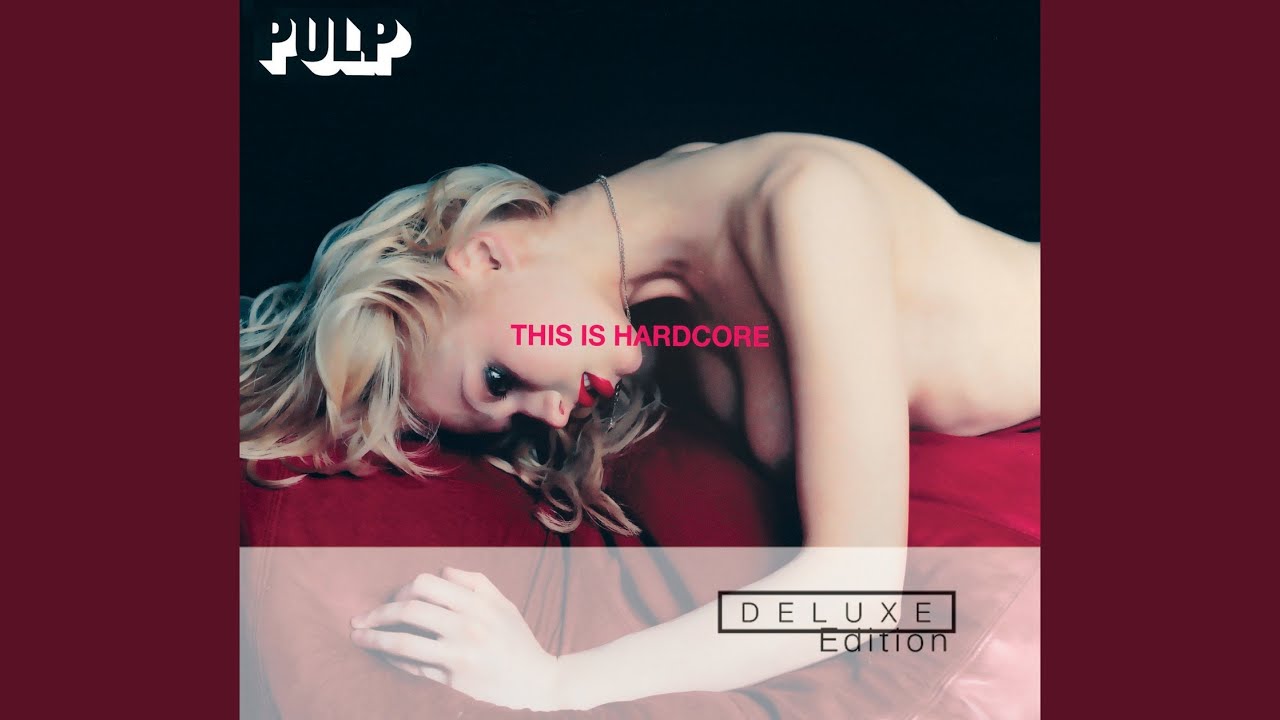

Thankfully, not everyone was buying it. In the sleeve notes for the deluxe edition of Pulp’s masterpiece, This Is Hardcore, Jarvis Cocker recalled watching television coverage of Labour’s giddily congratulatory election night party on the balcony of London’s Royal Festival Hall. "As I watched Tony Blair punching the air to the strains of D:Ream’s ‘Things Can Only Get Better’," he writes, "I thought to myself: Is that so?"

Cocker would later be inspired to write the song ‘Cocaine Socialism’, prompted in part by a turned-down invitation to join the Blair support campaign, but also by noticing how ubiquitous the drug had become in the artistic rush of mid-90s Britain.

"Now I’ll get down to the gist / Do you want a line of this / Are you a socialist / Well you sing about common people / So can you bring them to my party and get them all to sniff this and all I’m really saying is ‘Come on and rock the vote for me.’"

The prevalence of cocaine had certainly, for some, fuelled their part in Blair’s ‘new British confidence’. Damien Hirst, whose art was crucial to the success of ‘Sensation’, made no secret of his fondness for the drug. Similarly, Noel Gallagher would later claim that he snorted some in the Queen’s private toilet when he attended Blair’s Number 10 party.

Watching the BBC’s 1997 Oasis documentary Right Here Right Now it’s fairly clear that much of the swagger and arrogance comes with restlessness and dilated pupils. Thinly disguised as an exclusive, full access portrait of the band, it was ostensibly an extended promo for Be Here Now, their highly anticipated third album. In an act of extraordinary hubris, completely in keeping with the ethos of our Sensation Nation, it was released at 8am on a Thursday as opposed to the Monday morning norm – the band supremely confident that just four days’ sales were needed to make it a record-breaking number one.

Yet once the hype had become yesterday’s hangover, the reality of actually listening to it proved to be the aural equivalent of some of the more aggressively in-yer-face YBA art soon to (dis)grace the Royal Academy; shouty, hollow, bombastic, and (frankly) boring. Slap, bang, wallop. I can’t be the only person who felt disenchanted by the time the third track, the excruciating ‘Magic Pie’, had gone wrongly supersonic at the close of its interminable and unwarranted seven and a half minutes.

I know exactly where I was when I finally tried to give Be Here Now the benefit of a second chance. I was on a train to Glasgow to plan and then attend the funeral of my mother, who had died after an unexpected stroke a week before. There was an eerie, static atmosphere among my fellow passengers, since that morning the country had woken to discover that Princess Diana had died overnight in a gruesome car crash in Paris.

In the midst of an all too personal grief, over the next few days I watched, slack jawed, as the Princess’s death became a spectacle where society appeared to have abandoned measure in favour of hysteria. That Diana died in such a tragic fashion was unarguable, as was the impact on her family and her sons. Yet the Sensationalising of this tragedy became a juggernaut of mass mourning. On the BBC news I caught a middle-aged man saying, "I never cried at anyone’s death in my family, but I cried over this." As the streets around Buckingham Palace and The Mall became a giant carpet of floral tributes and sympathy cards, I wondered: with this heady mix of new British pride and emotional overstatement, had we reached peak 1997? The ascendancy of surface over both substance and rationality?

In The New Yorker, the normally reliably acerbic writer Clive James, admittedly a friend of the late Princess, amped up the magnitude of this mass mourning. "The more you know she was never perfect, the less you, who are not perfect either, are able to detach the loss of her from the loss of yourself, and so you have gone with her, down that Acherontic tunnel by the Pont de l’Alma… London has gone quiet; the loudest human sound is the murmur of self-communion."

Elsewhere, on an American television show, his good friend Christopher Hitchens was more succinct: "We’ve been drowning in drool."

A fortnight on, while the tidal wave of flowers, teddy bears and love hearts was being cleared, a short walk away through Green Park the ‘Sensation’ exhibition was poised to become a media tsunami, ensuring that September 1997 would be marked by the twin poles of a Royal death and a manufactured ‘youthquake’ in British art history.

Writing in Time Out magazine, chief art critic Sarah Kent argued, "At the private view, the joke was that ‘Sensation’ will do for the Royal Academy what Princess Di did for the Royal Family – make glaringly obvious the dowdy irrelevance of the fusty institution." A sour quip, perhaps, since by unfortunate coincidence the gritty portraits of every contributing artist featured in the show’s catalogue had been specially commissioned from the insider paparazzo to the YBA scene, Johnnie Shand Kydd, Diana’s step-brother.

Just as Be Here Now had been met with reviews of unwarranted hyperbole, so too was the assured buzz that ‘Sensation’ would prove an unarguable historical milestone. Sponsored by the aforementioned Time Out, the publication was producing a special supplement tied to the show, widely distributed both with the magazine and at the Royal Academy itself, giving artistic context while boosting the importance of the work on show, and the canny eye of its curator/collector patron.

As a filmmaker and sometime art writer who’d worked with some of some of the prominent artists, I was commissioned to write a piece on Charles Saatchi’s stature as a collector. The final text, which was far from damning, referenced what I cheekily called the ‘Sandro Chia Incident’ – a moment in the 1980s where Saatchi’s sudden offloading of this Italian painter’s work caused a permanent crash in Chia’s market value. Closer to home, it also carried an insider anecdote of one prominent YBA refusing to sell Charles any more of their work. When asked why, the response was a frank "I don’t need the money right now". Naively, I thought that as an independent voice it was important to be inquiring as much as laudatory.

I had either misread the workings of a nation where its socialist leader now had, as his right- hand man, something called a ‘Spin Doctor’ to counteract criticism, or more likely had simply upset Charlie in his moment of institutional glory. Whichever, many thousands of copies were printed, but they never found their way onto the newsstand, nor the grand staircase or shark-infested galleries of the RA. In the end it didn’t matter – ‘Sensation’ was the highest attended exhibition of contemporary British art for fifty years. Its fairground ride of what the Marxist critic Julian Stallabrass dubbed ‘high art lite’ predated the future mass-market success of Tate Modern.

Much of the work that was on show is forgotten beyond the hits, two of which stand out in the context of its time. ‘Dead Dad’, by Ron Mueck, was an eerily lifelike, pale-skinned waxwork of the artist’s late parent, but reduced in size so the body had a fragile, unlifelike aura. According to security guards at the RA, not merely was it the most popular piece in its gallery, but people were actually weeping when they stood around it. Similarly, Tracey Emin’s appliqued tent, ‘Everyone I’ve Ever Slept With’, embroidered with the names of everyone she had shared a bed with (sexual or otherwise) had lines of people waiting to go inside. Both – poised at the intersection of emotion and voyeurism – were perfect talismans for the Spirit Of 97.

As the country forged ahead into 1998, its champagne supernova for now unabated, construction began on the peak symbol of the new maximalism – the Millenium Dome. Tony Blair, high on his electoral victory, proudly announced that it would be "Britain’s opportunity to greet the world with a celebration that is so bold, so beautiful, so inspiring that it embodies at once the spirit of confidence and adventure in Britain and the spirit of the future in the world." It was 1997’s bluster blown up to epic proportions in an overblown domed tent nobody would ultimately really care for.

Much like the Sensation artist Ron Mueck’s five metre tall figure of a grossly enlarged crouching boy that was the centrepiece of its ‘body zone’, the Dome physically embodied the arrogant and confused largesse of Vanity Fair and New Labour’s belief that we had never had it so good. But the comedown from 1997 was inevitable. The Dome was the Be Here Now of grand public projects – shallow, hyped, hollow. Not until Danny Boyle’s Jolly Roger Olympics ceremony in 2012 would we see the like again.

But back in 1997 there was one last hurrah to come. In December, as Sensation entered the final month of its run, the predictable tabloid scandals were very much yesterday’s news. Nevertheless, The Young British Upstarts – so often lazily compared to the punk movement – finally got their Bill Grundy Moment.

Reacting to criticisms that the 1997 edition of the annual Turner Prize for art was exclusively made up of video and installation art, the Prize’s sponsor, Channel 4, decided to run a late-night live discussion programme enquiring ‘Is Painting Dead’? I would be one of its producers. Alongside a panel of artists, critics and art historians I had managed to persuade Tracey Emin to take part.

Tracey had been enjoying the lavish hospitality of the Turner Prize dinner beforehand, which, combined with medication for a hand accident, had made her by far the most ‘refreshed’ member of the panel. Halfway through the drearily earnest discussion, she broke loose.

"Are real people actually watching this?" she wondered out loud. "I’m the artist here from that show, Sensation. I’ve had a good night out, I’m drunk, I want to be with my friends." Finally, she’d had enough. After a comedic struggle to remove her radio mike, hampered by a splintered finger, she got up, walked off with gusto with a cheery "Bye everybody!", then disappeared towards the darkness. While the esteemed critic David Sylvester leaned forward and launched into a lugubrious speech on Turner’s ‘Fighting Temeraire’, Emin exclaimed from the half-light a final, triumphant, extremely 1997 word…

"Excellent!"