"…we started making what we call ‘style’ by writing rhyming lyrics that went on and on without finishing… continuous style. The way I see it, some MCs live off six lyrics for years and years, never changing. Whereas we’re on the move all the time because time is running, y’know… Smiley and I took a break once and developed 10 new lyrics each and then appeared at the Nottingham Palais. We chatted on the mic non-stop right through to the end of the evening. A wild feeling…"

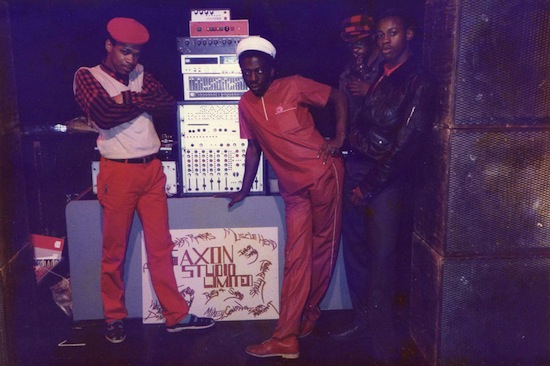

Smiley Culture & Asher Senator from Saxon Sound, in the NME, 1983

Sometimes I want to understand more, but so much of the thrill of pop is down to that which utterly resists such confinement. See: dancehall. I’ve never had much of an idea exactly what the fuck’s going on in a lot of the soundclash tapes that have come my way, but I do know that’s partly why they so often excite me. I know that sense of WTF is what’s always excited me about all Saxon Sound tapes – listen to any of these clashes from the early 80s on YouTube (and there are dozens, with particularly rich pickings between 82 and 85, by which time SS gained an ‘official’ release on the awesome Coughing Up Fire album) and you’re confronted with the necessity of having to totally overhaul the official version of British music you’ve been reared and raised on. Of course, when reading any history you look between the lines, you look at what’s been left out, particularly in any history of UK music, this entity so splayed and lashed and divided by lines of class and race it’s a temptation to forget about what doesn’t get heard any more, and just to be grateful for what can survive.

Most of what’s been written about post punk and new pop, that dizzying five years of innovation from 78 to 82, sees things as a musical rather than lyrical development, and focuses on those bands you know and love making the classic albums you know and love that themselves touched on a rich lineage of anti-classics you know and love. Like you I’m sure, I know and love all of them. But to hear something from that time that absolutely turns that (anti)canonical safety on its head, taps you into a whole bunch of British people making music whose main resource wasn’t a canon of alternative music made by experimental psychonauts. Rather you hear old-testament prophesying and civil-war-borne production line doom about the end times, and inevitably such uniquely sourced and utterly untalked about music touches you more now than all that reshuffling and reiteration of the usual pack of underdogs. Saxon still set such bombs off in your day, thirty years on. Can’t ever get enough of these Saxon Sound System tapes, although wish even more had survived, to further flesh out my growing apprehension that in Tippa Irie, Peter King, Asher Senator, Maxi Priest, Daddy Rusty, Smiley Culture and Papa Levi, Saxon basically assembled thee greatest crews of lyricists and DJs that have ever existed in the UK. Of course, it was no accident that so many of those names ended up signed to majors, but crucially the ‘importance’ (which is massive) of these fuzzy, distorted, sometimes barely-musical, decayed transmissions, doesn’t obscure the sheer pleasure they give, how compelling they remain as listening experiences. And just how much Saxon Sound owned things everywhere they went. They dominated and crushed all opposition. We should’ve shouted about them more. We should never forget to listen.

Saxon started in 76 in Lewisham as a purely party set-up, soon progressing to supplying sound systems at local venues, functions and weddings in and around the borough, and spending the rest of the 70s building their rep as the number one sound system in the UK. It was instantly clear to anyone who heard them that their MCs, dubplates and DJs were a cut above. Perhaps it was clear that anyone who heard DJ Peter King (who always had such a stunning ability to switch his voice, going from light speed chat to slow drawling cockney within the space of a syllable) at the DJ Jamboree dance in Lewisham in 82 was witness to the birth of a totally new style, the reverberations of which still seismically rumble through UK rap, grime and d&b. A style that in a sense cut the umbilicus between UK dancehall and Jamaican dancehall. ‘Fast Chat’, as the style came to be known, certainly had its antecedents in the artists that Levi, Smiley, Asher, Irie and King were raised on, the U-Roy, Brigadier Jerry and Nicodemus yard-tapes that were then circulating. But in the hands of Saxon the style got stretched out, extended, elaborated upon, given up to English as Londoners speak it and crafted by a consciousness that was pure black British. These were voices straight from the streets and shops and homes and intellects which struggled in Lewisham and elsewhere to come to terms with their own first and second generation immigrant identities. These voices struggled with their own parabolic relationship with international black consciousness. These are voices that walk a tightrope between slackness and roots every time they step to a mic, and that walk that line with charm, grace, humour, poetry and an almost-frantic inability to stop themselves. The only white guy to come close at the time was Mark E. Smith and that’s not an altogether daffy comparison – there’s a similar sense of deeply literary/poetic eccentricity and irresistible life to the best of Saxon’s output. Why Saxon? Why Lewisham? Why them?

Because if your day-to-day life tells you you’re at the margins, that you’ve got to remain silent, try and sneak by for fear of violence, for fear of bigotry, then when you get that mic in your hand there’s a very real danger no-one will be able to stop you talking. The ‘Fast Chat’ style enabled the artists on Saxon to say the things they had to say in a totally unique way, to push themselves and their experiences out as compellingly breathless art. It was as complete and simultaneous homage and immolation of a ‘homeland’ culture as Two Tone was, and should be listened to at least as regularly. ‘Rapid rappin’ was another name for the style Saxon pioneered, and it fits. At a time when the UK was just waking up to hip hop Saxon were delivering British rhymes, lyrics that could only have been birthed in the minds of British people, delivered with supreme finesse at dizzying speeds, freestyled over thumping bass-heavy beats to a point where sometimes all you can hear is a 2-speed kick drum pulse and somebody’s deepest and darkest, funniest and lightest thoughts coming at you like a nuclear train. Saxon Sound were perhaps the only British artists to get close to the kind of thing The Treacherous Three and Run DMC were pulling over in NYC at the time, even though how conscious of hip hop Saxon were has been lost in the mists of time.

Peter King explained the birth of the fast-chat style in an 85 issue of Echoes:

"A lot of English MCs was chatting like yardies, they weren’t trying to be original. I heard a lot of MCs copying and pirating, not entire lyrics – just the style. It all became rather the same … I did the fast style in 1982. People was already coming to Saxon but they used to love the fast style … People from other sounds used to say the ‘fast style’ was bad. They come to me and say ‘drop it in now’, in the dance so that they could hear it. Everybody was doing a style off a it – just said, well, cool runnings, at least they know who originated it."

Listening to the tapes, you hear Levi, Senator & Irie in particular stretching the possibilities of breath, of thought, of throat. Nothing compares to it – nothing contemporary at least – but it does recall later work by Shut Up And Dance, London Posse (both of whom were regular attendees at Saxon parties), or the most frenetic, mind-blowing grime to come much later (listen to Saxon tapes, then listen to Sir Spyro’s shows on Rinse and draw your own connections). There’s also a warmth, a humour, a turn of phrase simultaneously so English and yet so revolutionary you frequently have to note down where you’re gonna rewind to, just to check you were right to believe your ears. Just as Jamaica had discovered its own ska sound in 62 beyond merely copying American r&b sources, so you can hear in tapes from 82 onwards Saxon discovering their own sound, a new way of both grounding themselves but also propelling themselves into totally new territories lyrically and musically.

In fact, Saxon’s lyrical innovations offer stark counterpoint to what was going on in Jamaican dancehall at the time. A waning of political emphasis in Kingston, a growth of slackness and a proto-hip hop kind of assertive individualism opened up that space for Saxon to reaffirm the lost Rastafari consciousness of roots reggae, apply that dialectic to dissecting the ravages suffered by young black Britons in Thatcher’s first two terms. It’s not as simple as a rejection of Jamaica’s changing lyrical emphasis though – there’s still plenty of slackness in these tapes, these guys were too big fans of Yellowman to totally excise that stuff and you wouldn’t want them to. And as Saxon started playing and winning clashes back in Jamaica, that speedy style fed back into Jamaican dancehall itself, reinvigorating a style that had only fleetingly been hinted at before. Listening to Shinehead or Supacat from later on in the 80s it’s clear that Jamaica fed back Saxon’s impetus and explorations – that Jamaican crews returning home after battles with Saxon had been infected a little by just how odd, just how convincing Saxon were. It’s Saxon’s fluidity, their ability to melt together their roots, their present, and glimpses of the future in their music that makes these tapes so compelling. You can hear the crew’s diasporic disconnection get fused, get fixed and lived with: an incredibly liberating, joyous thing. Never just bleak, though sometimes bleak, never just happy, though often happy, Saxon summed up the defiance, despair and triumph of their times like no-one else, stylistically AND in terms of the topics and things they chatted about. Also of course it helps that, in comparison to Jamaican tapes from the time, tapes of clashes involving Unity, or Batman Riddim, or Coxsone or Saxon in England are just more lively, funnier, with way more crowd interaction and way more bedlam. These tapes document a desire to party hard, because the Monday that beckons will be hell, because the mean time between dances is a mean time indeed.

In retrospect, it was inevitable that Lewisham would be the birthplace of Saxon, the place they so often returned to. After all, it was Lewisham where Jah Shaka’s record shop opened up; Lewisham where Jah first started his dub soundsystem Shaka Sound; Lewisham that contained the Moon Shot Youth Club which was raided and vandalised by police in 75, adding to tensions that would grow and explode into the Battle Of Lewisham in 77. It was Lewisham that was witness to the horrors of the New Cross Fire; Lewisham where the NF and other fascist groups focused their terror and thuggery, making every walk out for young black kids an exercise in running the gauntlet of hatred and violence. You can hear that tension teasingly hinted at in Saxon tapes, even if the main impetus is liberation and joy – the sound system, the clash, the dance as safe haven, as transcendental refuge, a place where black unity and autonomy was celebrated, a space where pleasure and politics could coexist. Dr. William ‘Lez’ Henry, who started out as a soundboy with Jah Shaka, was in no doubt about exactly why Lewisham would prove a fulcrum for British dancehall, as he explains in this fascinating interview from 2013:

"They were alternative public arenas and alternative public spaces. That’s exactly what it was. DJs in the UK were articulating about absolutely everything; from love to hate to life and death.You know they say that hindsight is a fine thing because when I was immersed in the culture and DJing as Lezlee Lyrix, although I appreciated certain things, you don’t really understand just how profound the nature of what you’re doing is until you reflect on it. And when I was doing my doctorate work, I concluded – and I’m not asking people to conclude with me, it bothers me not if they do or don’t – that what was being articulated in reggae sound systems in the UK from probably 1981 to 1987 is probably the most pro-black, African-centered voice to ever come out of the UK. We governed that space. We were judge, jury and executioner of what happened. It was almost like an autonomous space in that sense, and a self-regulating one. Personally, I don’t think people really appreciated that. Especially, in the contest of the Black-British sound system and DJ culture … people would be articulating what you could do to get yourself out of your situation. What you can do about a particular situation. That’s why on the sound systems, the DJs would talk about everything from being stopped and searched by the police to how to deal with love problems. The focus wasn’t just on race or racism. That was just one aspect of our live or our ‘livity’ as Rastafari would say. People need to understand that these were transcendental spaces and not just spaces of resistance."

In 2014, still topping the youth unemployment league table (JSA claimants currently outnumbering available jobs 14 to 1), Lewisham’s suffering continues in sight of the city, finding itself the victim of both all-new brutalising cuts to youth services by the coalition and all-too-familiar police tactics of racist stop and search, both before and since the riots of 2011. How much would Lewisham benefit from a transcendental space again, and from a set of artists who could summate and surpass these times as effectively and elegantly as Saxon Sound did? Needed now more than ever, Saxon Sound and the art they made is an 80s you’re being kept from in most nostalgia from that decade. Get that wild feeling and then go and find who’s doing this now and report back to me. Saxon Sound for life. A wild feeling.