The ghosts and echoes of Manchester’s grim and glorious history lay dormant in the shadows of the city centre. It was a particularly dank day in the moody November of 1985.

It was a shame winter had to arrive – the summer and autumn had blessed the city with unlikely sunshine and a welcome jolt of musical activity. This had centred on the opening of two extraordinary venues – Colin Sinclair’s Boardwalk, literally hammered together by his father in a Victorian schoolhouse on ghostly Little Peter Street, and the larger International Club in Longsight, powered by the legendary DJ and booker Roger Eagle. Both clubs would help to tug energy away from The Haçienda, bringing in a new breed of guitar bands from the USA.

Despite the NME’s insistence that Manchester was "a city without a scene", a whole swathe of disparate acts enlivened venues of all sizes. This was celebrated in the sunshine of Moss Side’s Platt Fields park in August with the free International Youth Year Festival, featuring new league leaders Simply Red, supported by James, Easterhouse, Marc Riley & The Creepers, The Jazz Defektors and Kalima. Beyond this core lay embryonic outings by The Stone Roses, Happy Mondays and various musicians who would soon morph into Inspiral Carpets. The seeds of Madchester had been sown. Until this bright new dawn, Manchester’s big three – The Smiths, New Order and The Fall – seemed to have eternal dominance. Despite all this frenetic musical activity, a curious paradox remained. The Smiths in particular were entering arguably their greatest phase, amid rumours that their next album, The Queen Is Dead, would surpass even the glories of their first two.

The city had fallen into a similar state of flux. Although technically pre-regeneration, and a full nine years before the IRA’s bomb triggered full-scale redevelopment, Manchester was already moving slowly away from its industrial past. In 1985, three years after the opening of The Haçienda, the genteel Cornerhouse arts centre, cinema and cafe took over the carcass of a former ‘mucky film’ cinema. People had started to – gasp – live in the city centre. Even Roger Eagle moved into a development perched directly on top of the ugly, cavernous Arndale Centre.

Morrissey had moved to London and maintained a Northern link by buying a sumptuous detached house for his mother in leafy Hale Barns in Cheshire. The Smiths were embedded in ‘old’ Manchester and its dank, evocative nature seeps from their early recordings. Morrissey told City Life magazine in 1985 that, "the Manchester I knew is slipping sadly away."

On that November morning, The Smiths arrived on the train from Euston for a photoshoot with budding young photographer Stephen Wright that would cement their attachment to that old Manchester. Wright had spent time working in the Piccadilly studios of Kevin Cummins, whose work had helped define the city’s musical heritage since he began snapping the Buzzcocks and The Drones in 1976. It was a steep learning curve, but Wright had proven himself equal to the task. Branching out on his own, he operated from a bedsit in Longsight, using drinks cans filled with hot water to warm the developer. Wright was making an impact as a scene snapper and had benefitted from the new swell of local bands. Soon he would be working extensively for the Manchester Evening News, Black Echoes, Record Mirror, City Life and the council-run Manchester Magazine. (His work for the local glossy Muze Magazine was perhaps not mentioned when he approached The Smiths – the band were embroiled in a legal battle with Muze at the time.)

He had taken live shots of the band at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall in 1984 – full Moz classics, energised flower whirling and ironic pout – and had optimistically written to Rough Trade about getting some kind of commission. To his amazement, Morrissey said yes.

"I was really nervous the night before," Wright says. "I remember sitting in my room, realising that this actually might be a genuine cover shot."

Had Wright understood just how precarious his position was, given the legendary and sudden ‘changes of vision’ that Morrissey often succumbed to, his state of nervousness might have been unbearable. As it was, he set off armed with a naivety that Morrissey fully anticipated (and perhaps preferred to the assured cool and certain brilliance of Kevin Cummins). Wright met the band at Piccadilly station. Rough Trade’s multitasking ‘press officer’ Jo Slee (aka Jo Novark) outlined the brief – a link between the band and an iconic setting, perhaps a shot at Victoria station, or the Arndale?

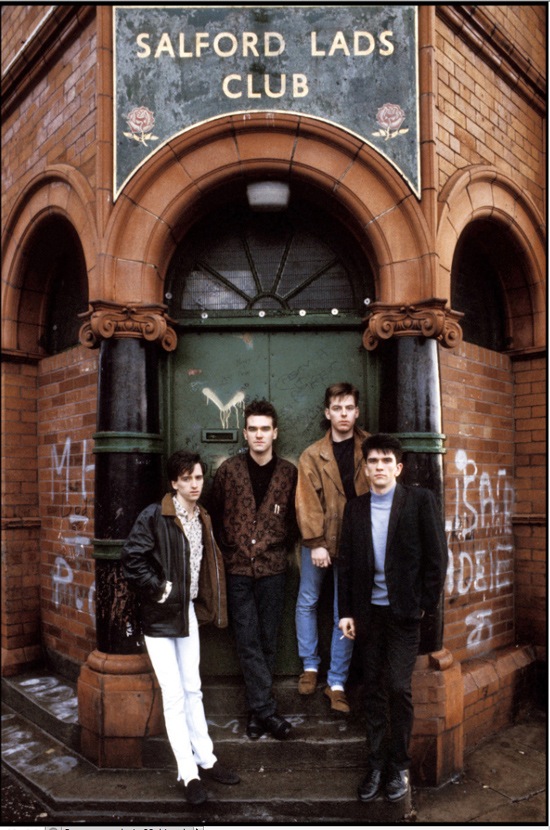

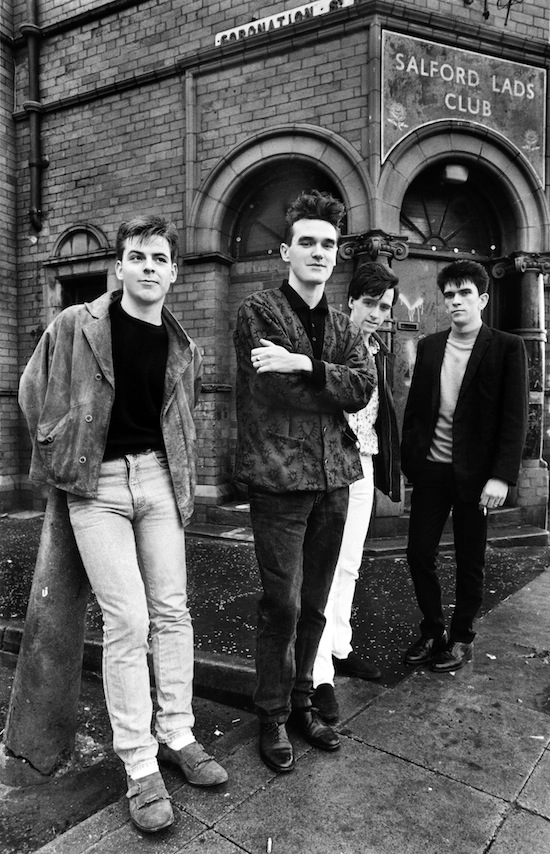

"The Salford Lads Club shot was entirely Morrissey’s idea," says Wright. "It showed that Morrissey had such a brilliant and realised vision."

The Smiths, Slee and Wright bundled themselves into a taxi and arrived, 15 minutes later, at the Lads Club on a day that was darkening by the minute. It was a dour, bitingly cold scene; Wright, fan-turned-photographer, was armed with just his £150 Nikon FE. And in that simplicity lies the key to the shot. In 1985, the gaudy snaps and videos of the second age of pop still lingered in recent memory. Could any picture be more perfectly the antithesis of Duran Duran in ‘Rio’?

"I had no idea that it would become such a famous shot," says Wright. "I was just worried about making fundamental mistakes."

It remains a brilliant and strange shot, with Morrissey in his BodyMap cardigan (more Covent Garden than Eccles) looked heartily self-assured while Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce simply lurk. An exhausted Johnny Marr huddles from the cold and stares meekly over the singer’s left shoulder. Above them, and above adjoining Victorian arches, the Salford Lads Club banner to the right and, sitting on the eaves, the Coronation Street sign.

Johnny Marr told City Life magazine: "I seem to remember some kids having a go at us, but it all passed by in a flash. I do recall seeing the photos. I said, ‘These are great – but don’t use that one.’ Of course, that was the one they eventually used."

It wasn’t without mild controversy. Morrissey’s decamp for London – and, later, Malibu and Italy – certainly distanced him from Salfordian endeavour. (Mark E Smith once told me, "All that Salford Lads Club shite… Morrissey doesn’t know Salford from his fucking, bloody arse, does he?") Admittedly none of The Smiths were from Salford, but the Morrissey family home in Kings Road, Stretford, is only a couple of miles away.

Of course, neither Wright nor the band could have grasped the future of that image as they made their way to Victoria station for the second part of the shoot. Given Victoria’s grand facade and its interior with the tiled mural of Lancashire’s railway network, there seemed to be no reason why the station shots wouldn’t match the outing to Salford Lads Club.

"We couldn’t shoot at the station," says Stephen. "It was really too dark this time and something just wasn’t right." The excursion across the road to the chromed ugliness of the Arndale Centre was equally frustrating. The results of the day remained uncertain.

(Morrissey later sent Wright one of his trademark postcards on which, in standard spidery scrawl, he proclaimed, "A sweeter set of shots was never taken." Years later, and completely out of the blue, Morrissey sent Wright to take shots of George Formby’s grave in Warrington. That image adorned the back cover of the first edition of Viva Hate, with Formby’s grave masked out, leaving only the leaden skies of Cheshire.)

Perhaps because of the Affleck’s Palace chic of their initial appearance – early-80s downbeat student in Levi’s, white T-shirts, secondhand overcoats, loose suede jackets, Doc Martens, etc – it has always been tempting to underestimate the power of The Smiths’ visual appeal. They were always a good-looking band, but their determination not to succumb to the airbrushed perfection of their pop counterparts did tend to shade this fact.

The aforementioned Kevin Cummins had already teased powerful imagery from the rather mundane threads and style of Joy Division. Cummins’ relationship with Morrissey weaves back to his own beginnings as Manchester’s premier punk photographer of the mid 70s. While Cummins hovered around Manchester’s ragged glitterati – Buzzcocks, Drones, Ludus, Devoto, Worst, Warsaw etc – the shy, young Morrissey watched from the shadows. Later, after Cummins allowed John Muir of Todmorden’s Babylon Books to publish a collection of his Smiths shots, Morrissey fired off another one of his postcards: "Kevin, I never knew tackiness was your forte." The great irony lies in the fact that Muir was also publisher of two of Morrissey’s pre-Smiths pamphlets: James Dean Is Not Dead and The New York Dolls.

Cummins’ most famous shots remain those of Joy Division, inside Tony Davidson’s rehearsal studios on Little Peter Street or on the snow-covered bridge in Hulme (although his recent book showcasing the Manic Street Preachers might challenge this), but he’s also forever linked to The Smiths. It was Cummins who initially captured the (possibly ironic) sensitivity of the band. My personal favourite set of Cummins’ Smiths shots are from September 1983 at Dunham Massey gardens in Altrincham (although for a long time Cummins thought they’d been at nearby Tatton Park).

Cummins recalls: "The Dunham Massey session was different because it was a softer approach to a band shot. I’d normally use the elements found in an urban setting, but with The Smiths I wanted the grass and the fountain. I wanted to bring out their sensitivity as well as the slightly narcissistic side of being in a rock & roll band. The individual portraits of them staring at their reflections in the water do that perfectly."

And it helps if the subject understands the medium: "Morrissey is the perfect subject because he is very collaborative and very self-aware. He understands the importance of photography in rock & roll mythology."

Martin O’Neill is another photographer who helped make his name by teasing something special out of Joy Division – such as those shots of the band onstage at Bowdon Vale Youth Club, surrounded by flock wallpaper. O’Neill’s more documentary style paid dividends when he shot The Smiths at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall.

O’Neill: "The funniest thing I remember about the Free Trade Hall gig was going backstage and Morrissey’s mum was there. I got a picture of the two of them together and the NME used it with little photo-album corners on it, as if it had been taken from the family album. But my favourite shot was the ‘nipple’ picture, where he’s almost out of the frame. They were a dream to shoot."

I remember, back in 1983 when the band was just breaking, Sounds photographer Paul Slattery made a similar statement: "You don’t have to think – it’s like they’ve already done the work for you."

I remember that I wasn’t convinced – but time has proved them right and me wrong. The Smiths have since been the subjects of an extraordinary number of distinctive photoshoots, and the Salford Lads Club shot remains their most enduring image. Wright says, "It is the band that are classic, not the photo," but it should be noted that the sheer resonance of that quick shoot is almost unparalleled in recent decades. Not least the effect it’s had on Salford Lads Club itself – that crumbling edifice would surely have gone unnoticed without Wright’s portrait. Instead, the club has iconic status; it remains a magnet that draws Smiths fans from around the world.

It remains fully functioning as the Salford Lads & Girls Club, and a more thought-provoking building would be difficult to find; I visited it for the first time last month in the company of Wright. Although no longer based in Manchester, Wright still makes regular forays to Salford from his native Berkshire, often to attend to the desires of Smiths devotees wanting their picture taken on the same spot by the same photographer.

Wright recently granted permission for the club to use the famous image on the front of Queen Is Dead T-shirts, with the aim of raising money to send six young members on a visit to Red Cloud High School in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. Sales have been "astronomical". As a measure of thanks, the club recently granted Wright a lifetime membership and a benefactor’s plaque, where he’ll be formally acknowledge alongside an array of youth workers, councillors and, indeed, Morrissey.

The exterior may be iconic, but it does not prepare you for the cavernous evocation within. The ghosts and echoes that began this piece seem crammed into every recess. You can picture excitable laddish braggadocio at every corner. During our visit it was deserted save for workers on an essential upgrade. Each room seemed in a state of polished Victoriana; the museum-like spaces and walls were lined with fading images of boys en route to summer camps in the Isle of Man, Anglesey and Llandudno. Wright seemed assured and familiar with the layout, guiding me upstairs to the boxing ring and gymnasium. On one wall, the image of a smiling Rocky Marciano. What a day that must have been for the ragamuffin tribes of Ordsall.

And downstairs, the infamous ‘Smiths Room’. Small, cubic and fully lined with a thousand fan stories, mostly standing before that famous edifice. From Portugal, USA, Poland, Brazil… from everywhere! We were thrilled to discover among them, taking shameless place in the tourist parade, the check-shirted figure of Ryan Adams. (Adams is a noted admirer of Moz, of course, as the argument that opens his celebrated Heartbreaker album testifies).

The is another delightful little twist, too, about a link between the replaced wooden eaves of the Lads Club and the woodburner at local venue and rehearsal space Islington Mill, where Manchester bands of today gather. Paddy Shine, from Mancunian psych ensemble Gnod, explains.

"Bloody hell, that story has been getting around," he says. "And it’s true. I was burning the eaves of Salford Lads Club for a month or so in our woodburner. Cracking burn. I knew the lads that were on the job and I’ve always got my eye out for cultural landmarks to set on fire. I kept one piece as a fantastic bit of carpentry that you just don’t see nowadays."

Wooden beams from old Manchester warming the artists of 2015. It is a detail that, I am sure, Morrissey would appreciate.

Stephen Wright’s photos of The Smiths are available as limited-edition prints