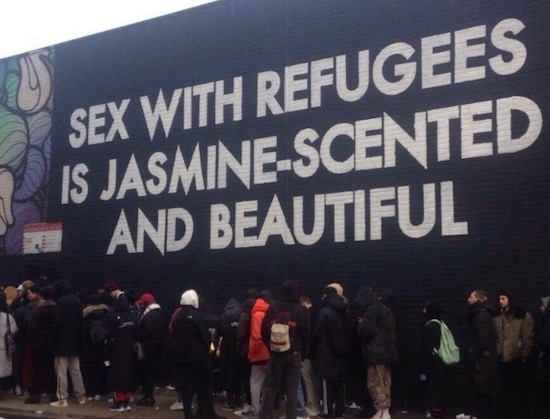

The other day, a line of text by conceptual artist-poet Robert Montgomery was painted in his signature white all-caps font on black on a wall in Shoreditch, round the corner from niche designer A Cold Wall’s sample sale. It read: "SEX WITH REFUGEES IS JASMINE-SCENTED AND BEAUTIFUL.” An employee at A Cold Wall denied that they had anything to do with it, ascribing it instead to Montgomery, an artist known for his guerilla art installations of poetic text, in the vein of Jenny Holzer with a side dollop of Barbara Kruger and Christopher Wool. He first came to prominence through papering over London billboards with dissociative text fragments reminiscent of the ‘Choose Life’ speech in Trainspotting, but has since gone on to create fire and light pieces that illuminate his bon mots.

Outrage was quick to follow, given that refugees are at high risk of sexual abuse, and the mural was swiftly painted over. In response to a Facebook post questioning his motivations, Montgomery apologised, saying that the words "were taken out of context in a way that [he] did not authorise” and that it was "excerpted from a much longer text that came out of workshops [he] participated in on how it might be possible to reverse the stereotyping language used to represent refugees in the mainstream media.” He added: "The workshop was about experimenting to find language that might reverse the tone of de-humanisation applied to refugees by certain media.”

Oh context, the escape route for a weak idea. Montgomery’s work is textual aphorism – it should literally speak for itself. Much like a good joke, good textual art should be self-evident. When something only works in context, its transcendental power is diminished. Even so, there is no context that would make that sentence defensible, short of it coming under the heading "Things not to say when attempting to humanise refugees.” Montgomery implies that someone other than him had access to his presumably private musings, and that someone signed this off in his name: it follows that either there is a shockingly incompetent editor within Montgomery’s inner circle who’s rifled through his desk and gone rogue on his personal documents with a highlighter, or that he’s just shunting the blame.

Montgomery also said: "It was not painted by me and was not intended as an Artwork [sic] by me.” Could this again be the work of the mysterious rogue agent, who alters other people’s signage without their express permission (coincidentally, a fitting description of Montgomery himself)? Or is it more likely to be a curious case of blame deflection? He may not have physically painted the mural himself, but they are his words, in his signature style, at a time when he is producing multiple murals across Europe to promote awareness of refugees’ plight (as evidenced on Instagram): that he didn’t take up palette and brush himself is irrelevant. Andy Warhol didn’t do all his own screen prints and Damien Hirst certainly didn’t make all of his spot paintings. What’s more, it’s not the medium that people are outraged over, but the words that he wrote – the part for which he has taken credit.

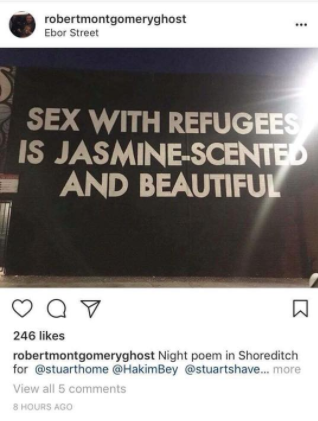

A screenshot is being shared online of Montgomery’s Instagram, showing a picture of the mural posted to his own account a few days before a public outcry led to it being painted over. The caption ‘Night poem in Shoreditch’ shows no signs of the dismay you would presumably display if your embarrassing private thought had been stolen and painted sky high on a Shoreditch building.

The photo is no longer on his profile, and the woman who shared the photo posted that he took the photo down after she called him out on it. Montgomery should really get rid of this implied saboteur, who not only steals and misrepresents his words in his exact style, but then posts happily about it to his personal Instagram account.

"The use of this particular text without its context was grossly mis-judged [sic] as it was clearly open to misinterpretation,” Montgomery wrote. It is not clear what interpretation he intended. Was it that refugees, too, are fuckable? If so, did he intend to reduce everyone, including displaced people who have suffered unspeakable horror, to objects from which to derive sexual satisfaction? Did he intend to display an entitled attitude to sex, in which his appraisal of another as sexually attractive renders them a valuable commodity?

Perhaps he intended to depict refugees’ foreign provenance as alluring. He certainly connected the dots between their exotic viscerality and their erotic potential by describing sex with them as "jasmine-scented and beautiful.” If that was intended, rather than humanising refugees as intended, he’s fetishised them instead. He could have meant to sweeten what he considers an unattractive proposition – sex with a refugee – by telling us it’s "jasmine-scented and beautiful,” thus reiterating the exact concept he was trying to dissemble.

Whether he meant it or it was accidental is by the by: it’s sloppy to leave the possibility of so many unpleasant interpretations when you are using a medium that can preclude them. The openness of its meaning has, in fact, been jumped on by the xenophobic – exactly who he claimed to wish to tackle – who are now tweeting in their droves: "Should the hundreds of women raped by migrants be told their attack was jasmine-scented?” (NB: the statistics on this are unverifiable or inconclusive.)

Perhaps he meant well, and the problem is that it’s superficial. There is a popular, if trite, sentiment that refugees are ‘human, just like us’, and a concomitant belief that art can and should be used to spread the message of our shared characteristics: we, the benevolent white humans; they, the beings criminalised by the Daily Mail and Brexit voters (boo, hiss). Yet good intentions are not enough to rescue the ‘We’re all the same’ trope from setting your teeth on edge. It’s shallow – thus rendering any art based on it rather lacking – and in its disregard for difference, it irons out cultural variations in favour of a homogenous image of the world, made in the speaker’s own likeness. It’s always "they’re just like us,” never "we’re just like them.” Maybe Montgomery intended to convey that the reader and refugees are on the same level, all one in his work’s likeness – detached, urban, neon-lit dreams of bodily communion through coitus – which, to some, has a certain disaffected romance.

But the ‘We’re all the same’ perspective ignores the chronic, systemic and violent disadvantages people of colour have had to face – and still do. What staggering oversight to assume that a refugee and a Shoreditch urbanite might arrive at a sexual encounter in equal standing. Refugees – men, women and children – are extremely vulnerable to sexual abuse and trafficking. They entrust their lives and bodies to people smugglers who may force them into sex work. They may have been raped by armed men (which is why they are refugees). They may live in makeshift shelters where they are not safe from intruders. They may turn to sex work through desperate poverty. In a year when it’s been top of every news agenda for months that even the rich and famous have not been safe from sexual abuse, it is quite a feat to be so tone deaf to sexual politics.

Montgomery is a man who, as he purports in his apology, supports numerous refugee charities. As mentioned above, he is currently in the middle of a series of murals raising awareness of the refugee crisis and has also contributed a piece to be sold at auction to raise money for charity. This mural depicted a wildly inappropriate statement for someone trying to help, and smacks of artistic conceit: daring to find the taboo fuckable. Maybe it’s essentially the art version of "I love my curvy wife.” If he has positioned himself as a post-woke provocateur, he has revealed his own biases and self-congratulatory ethos – "Look at me, my dick does not discriminate” – and then pulled a Taylor Swift and tried to exclude himself from the narrative. In this misjudged mural and obfuscating apology, this street poet looks as manipulative as the ads he’s trying to replace.

With thanks to Olivia Waddell for data on refugees and sex trafficking.