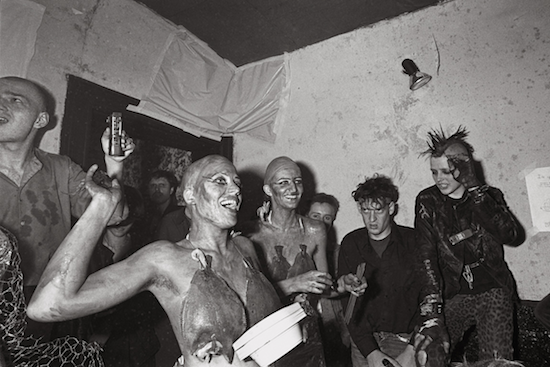

Mermaids at the Wassermusik Festival, 1982, by Anno Dittmer

In the autumn of 1998, after graduating university, I was backpacking around Europe when in Barcelona a stranger mentioned to me that Nick Cave owned a bar in Berlin. Returning to the States, I relayed this information to my best friend Andy and, without doing any further research whatsoever, we decided to fly to Germany to find it.

In those largely pre-internet days, without even knowing the name of what we were looking for, our sheer excitement had us genuinely believing we would get off the plane at Tempelhof Airport, ask the first person we saw, ‘Which way to Nick Cave’s bar?’, and then spend the rest of our trip living it up in the wild world of its confines. Instead what followed were nine days of confusion, thwarted plans, and perpetual drunken misery. Including a two-and-a-half day hallucinatory absinthe hangover that saw us wind up in Prague. [In 2019 I began telling the tale of this epic misadventure on stage and eventually wrote it up as a book.]

After 20 years we increasingly came to doubt that Nick Cave ever owned a bar anywhere. Then one day I Googled the phrase “Nick Cave’s Bar” and was shocked to find another result besides my own promotion for the shows. On author Hattie Holden Edmonds’ site, there was mention of “hanging round Nick Cave’s bar” and I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Further investigation proved that a bar similar to what we had imagined had indeed existed during the early-mid 80s, we were just 15 years too late. Somewhere where music blared, drink flowed, violence seethed, and art was lived. Where the likes of The Birthday Party, Wim Wenders, Alan Vega, Jim Jarmusch, and Christiane F, to name but a few, had been spotted within its walls. Although he didn’t own it, could this have been where the legend I heard of ‘Nick Cave’s Bar’ had sprung from?

Risiko stood at 48 Yorckstraße in West Berlin, in a Turkish immigrant neighbourhood still bullet-riddled and derelict from World War II, on the border between the Kreuzberg and Wilmersdorf-Schöneberg sections of the city. “Most of the nightlife in those days was centred in those two areas,” Blixa Bargeld, who bartended at Risiko during Einstürzende Neubauten’s early years, explains.

“One of the reasons why it was full was that everybody either coming back from Schöneberg going towards Kreuzberg, or the other way around, had to pass it.” Blixa is quick to dispel the myth that The Birthday Party coming to Berlin had anything to do with Risiko’s popularity. “They were probably there two or three times, except for Tracy Pew. For a whole month he came every evening, brought his own bottle of Jack Daniels, sat at a table drinking it all night, and then left again [laughs]. Risiko’s popularity was more due to its location and the fact that all different scenes mixed there – the punk scene, the gay scenes, the drug scenes, night party crowds, I don’t know how to label all these people. It was mainly a lot of individuals, who would come every night.”

Musicians, filmmakers, painters, poets, and punks crammed into its small three rooms, revelling long into the morning hours. Its clientele didn’t arrive until after midnight, usually more towards two or three AM after hitting some of the other local clubs – SO36, The Jungle, Metropol – and, in this city with no curfew, could stay until the bar felt like closing, often at nine or ten in the morning.

“It was a home from home, in a way,” musician and B-Movie: Lust & Sound In West-Berlin 1979-1989 star Mark Reeder recalls. “It was where everybody ended up. In the 80s, the flats were all coal oven flats. People didn’t have central heating. You’d share a toilet out on the landing with your next door neighbour. In the winter, your flat was freezing, and you had to go get coal from the coal merchant. And if you’ve been clubbing it all night, getting leathered, the last thing you wanna do is have to go get coal. So we’d end up in the Risiko cause it was warm there.”

West Berlin in the 1970’s was, by all accounts, grey and grim. A place few visited. Most I spoke to for this piece credit David Bowie and Iggy Pop with having a big influence on the emerging culture of the city. Not only with the art they made, but the fact that armed with visions of its 1920s glory, of Christopher Isherwood stories and the film Cabaret, these two singers came to Berlin to record in the mid-late 70s, helping to put the city on the map internationally and inspiring other artists to move there. The rents were cheap and one could survive on little income.

Also, despite military service being required of West German residents, men registered as living in West Berlin were exempt from joining the army. Mark Reeder laughs, “So anyone who was a pacifist, gay, weird, artistic, or just a shirker, they’d all come to Berlin.”

Although it was an island in occupied territory, surrounded by the Wall, West Berlin felt free and liberal. Journalist and Sexorzisten singer Oliver Schütz remembers, “The more interesting people, who were more artistic and extreme, needed freedom to develop and they couldn’t realise that in their West German hometowns. Once you got to West Berlin, there were so many interesting places and people, so much to do, one hardly felt walled in. There were all these weird, interesting corner characters and you emotionally connected to them because they weren’t so polished. And all the drugs helped people open up as well.” Drugs were a big part of it. More on this later.

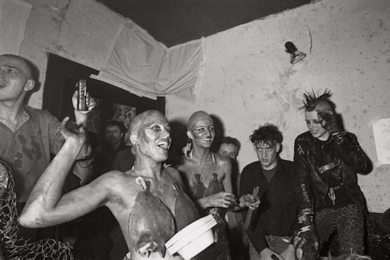

Alexander Hacke performing as Alexander von Borsig watched by Blixa Bargeld (in leather), Antje Fels, Stefanie Mahlknecht on the right. Photograph by Anno Dittmer

Die Tödliche Doris’ Wolfgang Müller laughs when I tell him that we were looking for a bar Nick Cave owned. This is a common response during my quest to find out more information about the infamous Risiko. Such mythologising was Müller’s reason for penning the 600 page tome Subkultur Westberlin 1979-1989. Freizeit. [West Berlin Subculture 1979-1989. Free Time.] Indeed everyone I spoke with acknowledged that in the years since Risiko closed in 1986, there has been much fabulation and altering of the facts. The German term for one who does so, Blixa informs me, is “Geschichtsklitterer”. Attempting to set such colourful varied history straight, Müller has two chapters in his book dedicated to the bar, ‘Risiko 1’ and ‘Risiko 2’, breaking up its story into two distinct owners and timeframes.

Originally one of the first lesbian bars in Germany, Blocksberg was named for the mountain peak that the witches are said to dance on during Walpurgisnacht (30 April, the springtime corollary to Halloween). Along with a few friends, Blocksberg regular Stefanie Mahlknecht soon took over the venue in 1981 with the intention of making a “free, creative space” for both lesbians and gays. They chose the name Risiko (German for ‘risk’) precisely because of the riskiness of such a venture. With almost no experience running a café, they were using the last of their money to open a place that would face much hostility towards its open policy. Soon after Risiko opened its doors under a logo combining the pink triangle and punk typescript, “a delegation of dykes stormed the shop, smashing the urinals in the men’s toilet with a sledgehammer”. Throughout its lifespan Risiko would also be the target of skinhead and right wing radical violence.

“It was always mixed,” Müller expounds, “not just lesbian and gay people, but everybody. You would call it queer in that way, but it wasn’t about orientation, it was more about being open-minded. A very creative place, with a sense of humour. Punks would order a cappuccino and the foam on top would be dyed with food colouring to match their hair – blue, green, pink, yellow.” Such a spirit saw the Risiko play host to an assortment of events – gigs, early showings of Jörg Buttgereit’s ‘splatter’ films, along with other, stranger, performances. One of these being the infamous Wassermusik festival with Die Tödliche Doris and Einstürzende Neubauten on 29 May, 1982. Müller explains, “It was a very chaotic thing. We had two bathtubs, Andrew from Neubauten (N. U. Unruh) used a metal one and I used a plastic one. We were both sitting there more or less nude in the water with Handel’s ‘Wassermusik’ playing very loud on the stereo. People were curious and came to see what would happen and we let the performance be very open in that way.” Three women served fish fingers while dressed as mermaids, their bikini tops made of plaice bought fresh from the fishmonger that morning. Blixa adding, “it ended up in a giant water orgy, people were doing whatever they could with water.” Stefanie Mahlknecht recalls “That was a huge mess. The floor was covered in four centimeters of water. It stank for weeks. Some were shocked. But it was worth it, it was fun.”

A video of the night exists and some of the sounds recorded were even released on CD by the US label Psychedelic Pig in 2002. As bathtubs in bars often do, one of these stayed in the back room and was incorporated into another event. Blixa says: “Because of the consumption of beer, there was always an enormous amount of empty bottles. There was another performance that was (laughs) meant to be musical, but the main element was Andrew systematically and rhythmically smashing one bottle after another into the empty bathtub while a guitarist and a bassist played with cardboard boxes over their heads. I recorded that on a tape recorder and it was later released as one side of an album. It was a fantastic performance.”

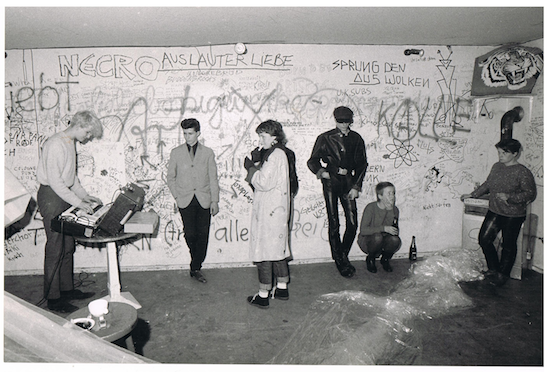

Alex Kögler by Evelyn Obermeier

Towards the end of 1983, Stefanie and co. were off to pursue other avenues and who better to take over the Risiko lease than a stylish, alcoholic, cocaine user who had recently come into some cash. Enter the one-and-only Alex Kögler. Blixa says: “Alexander Kögler had no experience as a gastronome, or anything like that, but he happened to inherit a lot of money. And he had no interest except spending it on cocaine and beer.” Mark Reeder adds: “It was very much a case of, ‘I’m going to have a bar so I can drink for free.’” Kögler was much-loved, very sociable and charming, always handing out free drinks, wearing tailored suits and looking a bit like Robert Mitchum. Schütz described him as “a careless lover of life. Very funny, with a stark sort of humour, but he also had manners.” Maria Zastrow, herself a prominent figure behind the bar during this second phase of the Risiko, with her exceptional musical taste, rockabilly look, and giant quiff, remembers Kögler as “one of a kind. He was really an interesting guy, but he destroyed himself completely. In a way of course he was the one who made it all happen with his inheritance. He was like a big baby, he never really grew up. He was our boss but he was also like our child, we looked after him. But he was amazing. He looked amazing. He would have his clothes drycleaned and delivered in the afternoon along with the liquor delivery [laughs]. He was very impressive.”

Kögler moved into the apartment above the bar with his girlfriend, Sabina van der Linden, and Risiko closed for a few months while she set about renovating the place. The pinball machine in the front room stayed but the cabinets behind the bar were replaced with a giant sheet of plexiglass, painstakingly handpainted yellow and black in diamond shapes (Blixa: “it looked fantastic”), while the back room was turned red and blue. But no amount of paint could cover up Kögler’s lack of experience in running a bar. Schütz who stayed in the flat above for five months during a period of homelessness recalls, “He never fucking cared. His room was a mess, bottles all over the place. He was a total cocaine addict, he wouldn’t even think about bills. You’d open the front door of the apartment and there would be piles of unopened legal notices on the floor.” Maria Zastrow tells of how, on the first night of the reopening, instead of adding the required second men’s room toilet to a bar of this size, Kögler tried to get around city regulations by hanging a giant sheet of transparent nylon in the middle of the room to act as a makeshift wall, claiming ‘now it’s smaller’. “People weren’t supposed to go to the other half of the room,” Zastrow laughs. “But of course everyone just started cutting it down and tearing it apart. The ‘wall’ only lasted for one night. Alex was so naïve.”

And then of course there was the money situation. Between the astronomical amounts of free drinks given away – Reeder says, “Most people drank for next to nothing. I don’t think I ever paid for a drink in the Risiko” – and Kögler’s raiding the till to buy drugs, there never seemed to be any cash. With Kögler frequently forgetting to order enough stock, out of necessity staff would often take what little money there was in the cash box to the petrol station around the corner to buy beer and vodka to then sell behind the bar. Blixa says: “Alex never really got his shit together so most of the time we ran out of everything including beer and oil and all the essential things that you needed. Often we didn’t even have enough glasses so we would cut the empty beer cans open and fold the rim inside so that we could fill them with drinks. It was dangerous, you could easily cut yourself.”

Kögler was also a huge music fan, getting obsessed with individual songs. Somehow hearing of how often he played ‘Aural Sculpture’, The Stranglers once sent a postcard to the bar to thank him. Maria Zastrow remembers him jumping around to his favourite music. “He always had these ‘hits’. Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s ‘Relax’ was his favourite song for a month or so, he played it all the time. He also liked glam rock very much. He loved Bryan Ferry, and wanted to be like Bryan Ferry with his suits. He wanted to be the best dressed man in town.” Blixa confirms, “Alex Kögler was a huge Roxy Music fan. And being a coke fiend, in the early hours one night he was playing ‘Mother Of Pearl’ endlessly on repeat. Two strippers were at the bar and for some reason one of them ended up being taken outside by a building site worker. They somehow managed to strap her onto a giant crane and lift her up over the rooftops while the crane drove around. Meanwhile we had the door open and ‘Mother Of Pearl’ was blaring in the background while Alex Kögler stood staring up at the spectacle with a bottle of beer in his hand. It was unbelievable, completely surreal.”

Music was part of the lifeblood of Risiko, and it was always ‘enormously loud’. The bartenders took turns DJing on the cassette decks, playing an eclectic mix ranging from rockabilly to Throbbing Gristle to pop hits of the day to Lee Hazlewood and Johnny Cash, Blixa even sometimes playing John Cage. Maria Zastrow, who on Elvis’ birthday would play only The King, DJ’d “stuff that no one else played at that time, even The Beach Boys. People hated me for that, because at that time they didn’t understand how great that music was.” Police would stop by about the noise, even once screwing the volume knob in so it couldn’t go above a certain level. But it didn’t take long for the bar staff to find a way to circumvent this and return the noise to its former glory.

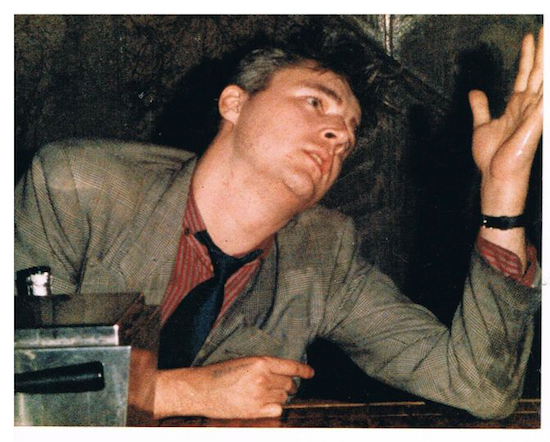

Maria Zastrow

And of course there were the drugs. “The fast ones,” as Blixa puts it. “Everything else we didn’t really want. That doesn’t mean it didn’t happen but we were not supporting it. This was before the time of ecstasy so the main thing was amphetamines.” Mark Reeder agreeing, “it was all cheap speed from Czechoslovakia.” Oliver Schütz tells of his own experience that seems emblematic of most patrons at the time. “At first I thought it was so cool to stay in the flat upstairs from the bar but it was actually the beginning of my biggest nightmare. I started taking speed as well and I couldn’t sleep. The music was so loud you couldn’t go to sleep until 10 in the morning and then the traffic started on the street out front. So you couldn’t sleep in the day, you couldn’t sleep at night, you couldn’t sleep at all, and on top of that you were on speed. I remember having a lot of nightmares from it all. Nightmares became our friend [laughs].” Like other scenes of the time too, heroin would make its way in, with visitors spying patrons shooting up in the corners of the backroom.

Skinhead raids continued and a doorman was soon hired. Maria says: “Holger was a great guy. He looked like he was super weak but he could be extremely strong. He hated fascists and right wing radicals, was totally on speed and always ready. Holger was on a mission to protect us because he thought the place was so important.” Kögler soon ruled that no more than three skinheads could be inside at any one time. The atmosphere inside was rowdy enough anyway. Artist Mike Hentz was once thrown through the front window during a fight, breaking both his jaw and the glass. Zastrow recalls, “The was blood and glass all over the place. We never called the cops, of course. It was too dangerous because there was so much illegal stuff going on in the place. So we had a big hole in the window. It was the middle of winter, around -20 degrees Celsius, and it was horrible. We taped cardboard over the damage, and it didn’t get repaired for half a year.” So much for being warmer than Mark Reeder’s flat, not that that deterred any patrons.

With Einstürzende Neubauten gaining popularity and the gathering chaos of the establishment getting on his nerves, Blixa’s time behind the bar came to an end. “On a very, very memorable night for me, I left. I decided, ‘I can’t take this anymore.’ There was a woman that I knew who had a really loud, obnoxious singing voice. And she knew that it drove me nuts. On this particular night at Risiko, she was sitting in front of me at the bar and of course at some point she starts singing. So I turn off the music and say, ‘Nadja, stop this!’, emphasising my words by pointing at her. And what does she do? She bites into my finger. I reacted by pushing her head down, which resulted in her throat being cut by the wine glass on the bar and she was bleeding from the jugular. Nobody saw this of course and everybody blamed me, they thought I had cut open her throat. I explained and then they were yelling at me, ‘Call the ambulance! Call the ambulance!’ And I said, ‘The telephone has been cut off for six months, I can’t call the ambulance.’ Somebody ended up going outside to a phone box, but when the medics came she refused to be taken away. She started a fight with everyone and people were yelling at me of course. At that point, I decided, ‘This is it. I can’t work here anymore. This is too much.’ So I left. It was already very late so I went to a café, and who comes in while I’m having breakfast? The singer. And she doesn’t even remember anything. The hospital, the bandages on her throat, all the rest. She doesn’t know what happened. And I thought [shaking head despairingly] ‘I can’t work there anymore. I am ok with just being a musician, I don’t really need to do this as well.’”

Risiko itelf wouldn’t last much longer. No one is entirely sure why it closed, but with the way its business side operated, with suppliers and rent rarely paid and bills piling up, it is no surprise that Alex Kögler was in over his head. As Mark Reeder puts it, “You can’t give away your drinks all night every night for years and expect to carry on.” In 1985, Kögler sold the bar to a lesbian couple, ownership coming full circle in a way, its doors finally closing the following year. Strangely enough, concurrent with the witches dancing on Blocksberg, the last night of the Risiko was April 30th – Walpurgisnacht. Filmmaker Uli Schueppel of Schueppel Films caught some of final morning on Super 8. At the end you can see Nick Cave and Nikki Sudden amongst the pack making their way up the stairs, leaving Risiko and heading to the Superfly discothek.

Maria reflects, “In a way, what was nice about the place was that we were all so different. Filmmakers, cleaners, punks, skinheads, artists, musicians, people with different kinds of tastes of music. Everybody had their own special thing, and also the clientele was very diverse. I met interesting people almost every day. And soon everything was changing. Nick left and went to England. Blixa was all over the place with Neubauten. Some people got into heroin and disappeared to more junkie hangouts.” The music was changing too. In three years the Wall would come down and the scene would shift to the electronic sounds coming out of East Berlin. But for those who lived to tell the tale, and many didn’t, Risiko was a central part of the city’s thriving cultural nightlife. Blixa observes, “It was very much anchored in what West Berlin was. It would be unthinkable to do something like that today.”

Aug Stone’s live album and book, Nick Cave’s Bar are out now