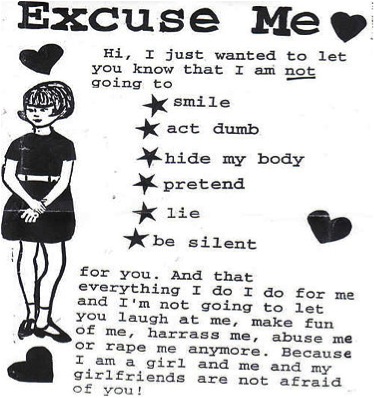

In the spring of 1993, 20 years ago, Huggy Bear and Bikini Kill toured the UK to promote the release of their split album Our Troubled Youth/ Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah (Kill Rock Stars/ Catcall Records 1993). Already heralded by a wave of pieces in the music and mainstream press, the riot grrrl movement had emerged into popular culture as a strident call to women and girls to break their silence on sexism and misogynist violence through zine writing, performance, consciousness-raising and political activism. A couple of weeks before the tour began, Huggy Bear had made an appearance on Channel 4’s infamous late-night show The Word, offering 3m 22s of situationist abandon in the form of third single ‘Her Jazz’ and later angrily detourning a show segment about pneumatic models Shane and Sia Barbi, better known as the Barbie Twins. When the moment of disruption ended with the band and friends being violently ejected from the studio and the carefully mediated pseudo-chaos of late-night programming resumed, my little group of friends, watching our tiny TV in the kitchen, found ourselves inexplicably on our feet.

…there’s a sense of urgency in the air right now it’s been growing for some time like we’re all starting to get it i mean REALLY GET IT things are burning collapsing we are watching rome fall…

Fix Me zine, Joanna Burgess & Erika Reinstein, 1992

Hello Petra,

My name’s LUCY and I’m 13. I am a RIOT GRRRL because I believe punk girls can should change the world for real!

Excerpt from BM Nancee letter, 1993

The UK tabloid press reacted with predictable derision to this emergence of the Real into mainstream discourse. Though Huggy Bear had long attracted the interest of the music weeklies, this was national attention on an unprecedented scale. Many dates on the tour attracted audiences far outside the imaginable demographic of a radical feminist punk rock/queercore soul hybrid. The tour is best memorialised by the excellent short film, It Changed My Life, by Lucy Thane.

Bikini Kill in the U.K. 1993 from Lucy Thane on Vimeo.

Thane’s documentary approach captures the excitement generated among young women hungry for feminist self-expression and a way into a punk/hardcore scene too long dominated by moshpit violence and sneering exclusivity. The film also hints at something of the atmosphere of violence that surrounded the tour following the tabloid press interest in Huggy Bear. After similarly inept coverage in the US by Newsweek and USA Today, Bikini Kill had become used to verbal and even physical sparring with men in the audience who resented their unapologetic grrrl-centricity, and many US riot grrrl chapters had a policy of media blackout for that reason.

Bikini Kill’s US shows were subject to frequent misogynist heckling and threats, and band members engaged their audience directly in the task of tackling any violence, asking cadres of girls to point out and eject abusers in the audience, or guard the band and van during loadout to prevent further confrontation. ‘Girls to the front’ meant more than a view of the band, or even a joyful reclamation of the moshpit for safer self-expression; it was a political strategy aimed at subverting the oppressive gender dynamic of punk shows, and a security policy for managing the violence that often resulted. The girls at the front were riot grrrl’s S1Ws, a response to colonised space and an open challenge to privilege (riot grrrl has often been criticised for its appropriation of critical race theory and the overwhelming whiteness of the movement, perhaps never quite so aptly).

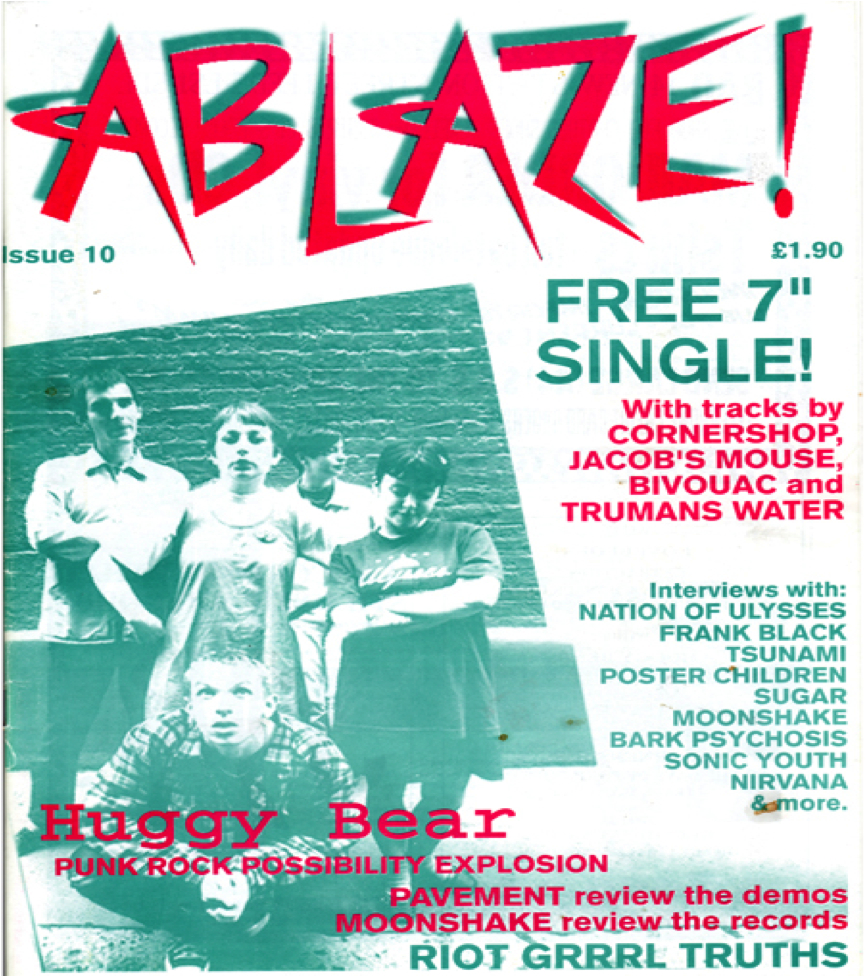

The tour’s most rapturous dates were in Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds, where Ablaze! zine had most effectively prepared the way. Karren Ablaze, its editor, published an editorial in 1990 written by Terry Bloomfield entitled ‘New Voices, New Guitars’, arguing for punk as a feminine form of expression. Issue 10 featured Huggy Bear on the cover and Ablaze’s own Grrrlspeak Manifesto for Girl Power International. "Girl Power intends to destroy the whole ‘civilized’ world, with all those dominant cultures based on corrupt, damaging gender roles – and replace it with something far better," she wrote. "The transformation: through catalytic noise-sounds and inflammatory literature, previously ‘impossible’ possibilities are unleashed. After a period of extreme energization a vision of the necessity and practicality of removing oppression in every sphere becomes apparent."

"For me it was a political movement," says Ablaze of her work at the time. "Feminist ideology was foremost; whatever kind of creativity or action that inspired was secondary. Personally I was reading radical feminists like Daly and Solanas; I understand that bell hooks was a big influence on the first riot grrrls.

"The key element for me was that girls could get together and change things. I put on the [Huggy Bear/Bikini Kill] show in Leeds and the venue, the Duchess of York, filled beyond capacity with more people trying to get in. Myself and other riot grrrls were overwhelmed by the numbers, particularly of girls in the audience, and several of us clambered onstage between bands to grab the mic… both bands had a great deal of power, they were on a mission. Huggy Bear live was like a hurricane, and explosion of energy and anger. Bikini Kill had a clear message to deliver, they wanted to empower all the girls in the room."

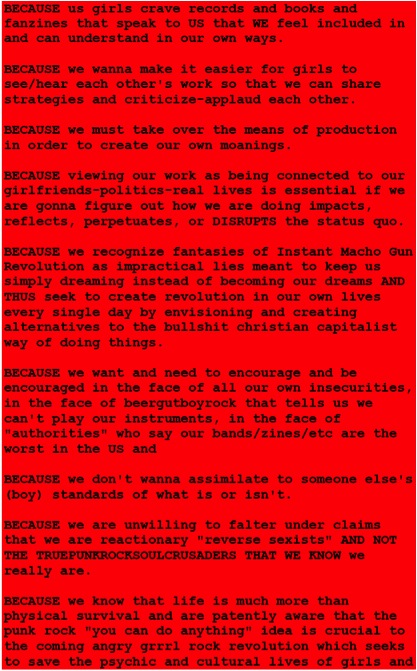

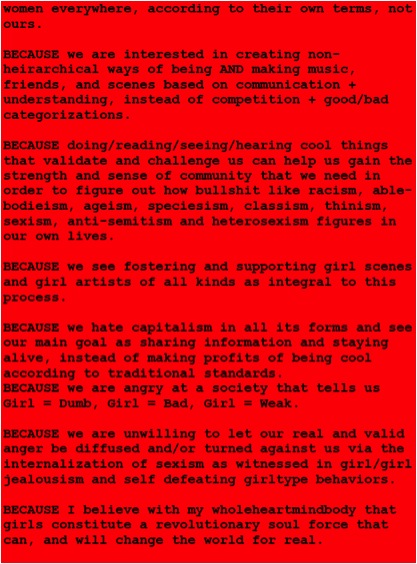

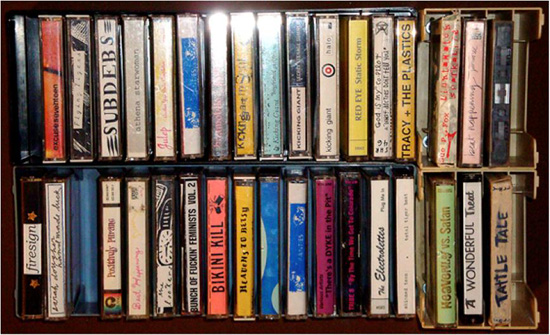

(Bikini Kill zine, issue #2)

The origins of riot grrrl are contested, its lineage blurry. For some, it’s adequate to say that the movement coalesced around the appearance of a handful of feminist punk bands (Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Heavens To Betsy) and zines (Jigsaw, Girl Germs) around Olympia and Washington, D.C. in 1990-91, and the simultaneous, though less notorious early UK riot grrrl scene in the form of Lungleg, Skinned Teen, Huggy Bear, and the Girlfrenzy and Ablaze! zines. Others point to a feminist musical continuum stretching back through Mecca Normal and the Runaways to the Shaggs in the US, or argue for UK riot grrrl as an offshoot of the joyfully shambolic C86 scene of the 80s. This riot grrrl YouTube playlist, guest-edited by Leesifer Frances of Riots Not Diets, gives a sense of the breadth of the form.

Photograph courtesy of Larrybob

But riot grrrl was far more than a musical movement: its project was to radicalise a generation of girls into direct action against sexism and misogyny, and to form a new slew of women artists, performers and writers who would drive sex-positive first-person feminist expression into the grassroots of everywhere. The by-now international Ladyfest tradition continues to place women’s creativity at the centre of feminist organising, but it’s the political provenance of riot grrrl that reveals its true legacy. DIY is a strategy, not just a sound, and riot grrrl’s impact has spread far beyond music culture. Though Girls Rock Camp is an honourable estate, and women’s representation in music still a thoroughly defensible goal, it is in the more explicitly political current feminist movements – Slutwalk, Pussy Riot, the prefigurative feminism of Occupy – that riot grrrl’s defiant mix of performance, direct action, and belief in the power of first-person experience to unite and liberate women and girls, echoes most strongly.

Young women at the New York City Slutwalk, 2011

I’m marching because my body is MINE and I can wear what ever I chose to. I’m marching for all those girls in abusive relationships that never leave and never call it rape and never report it. I’m marching for all those ignorant men out there who blame women for men’s vile actions. We blame ourselves anyway. We judge ourselves and chastise ourselves and hurt ourselves. Every day I am angry. Even in my dreams I am livid.

‘Why I Am Marching,’ Slutwalk London participant, 2012

(Jigsaw zine, issue #3, 1991)

Riot grrrl emerged in 1991 from the gender politics of the Bush administration, the Washington D.C. race riots and the Clarence Thomas hearings; it represented a widespread re-engagement with feminism as a survival strategy at a time of political peril for women, girls and other queer genders. Just so now, populist forms of feminist resistance are sorely needed here, as the UK reels through the coalition’s madcap programme of upwards redistribution. Austerity measures are aimed squarely at women and girls; our reproductive rights are once more under threat; domestic violence has risen by 19% over the past three years; around 2/3 of women in the UK have experienced mental health issues. Trans people and other gender minorities, whose liberation is intimately linked to any feminist project, are also facing similarly epidemic levels of mental illness linked to their experiences of discrimination and abuse. 2012 saw bruising public debate over rape culture and sexual violence in the form of the press furore over Julian Assange and Jimmy Savile.

Folded into these phenomena are the differences between us: between women in the global north and south; between cis women and trans* feminine spectrum people; between white women and women of colour; between disabled and non-disabled women. The movement materialising at this crucial political moment draws heavily from riot grrrl’s populism and performative strategy, but is aware of its legacy, its shortcomings and failures – its whiteness, its insularity, its failure to engage practically with queer and post-colonial feminisms – as well as its strengths. These new feminisms must dare to demand justice and liberation for all women, whatever our complex identities and experiences; not only to resist psychic death but to disrupt all oppressive systems. With this as its project, the Revolution Grrrl Style Now may finally have found its horizon.