Ricky Gervais describes a scene from his next sitcom, provisionally titled Black Comedy. "Anyway, so, it stars this little fat bloke, right, rich, and he’s got this black mate, so,

you know, awkward. So here’s how it is, right, get this, right, HAHAHAHAHAHA! He’s all done up as a minstrel, right, just relaxing at home, doing ‘Swanee River’ on the old banjo as you do, when the doorbell goes, right, and it’s only his black mate! And there he is, all done up as a minstrel, I mean, embarrassing, or what, HAHAHAHAHAHA!! Talk your way out of that! See, it’s funny ‘cos it’s real. That’s what’s happening to black people every day but no one wants to talk about it. Anyway, his black mate says, "Apologise." But why should I apologise? All right, I apologise. Yeah? Then Johnny Depp turns up, he’s all blacked up too ‘cos he’s playing Nelson Mandela in a (etc)"

What happened to Ricky Gervais? Did he fall from grace after The Office or was The Office actually a temporary, out-of-character, ascension to grace? Has he been spoiled by success, or has success merely allowed the true Ricky Gervais, in all his self-obsessive, disconcerting unpleasantness, to be given free rein and full exposure? Why does that opening, italicised paragraph seem more probable than satirical?

Gervais’s latest sitcom, Life’s Too Short, is currently midway through its run. Car crash TV doesn’t do it justice; watching it, week after week, is like standing by a foggy motorway, looking on as consecutive cars slide on the same patch of black ice, one after the other, careering sickeningly into the rear bumper of the one in front, and being helpless to do anything about it but grimace.

Life’s Too Short is not entirely unfunny; the stand alone celebrity segments do actually work, by and large, even if the shtick has become cloyingly over-familiar. As for what’s wrapped around these pellets of comic relief, however…

In The Office, much of the comedy derived from Brent’s excruciating, backfiring attempts to showboat playing out in front of stunned, mute, unsmiling co-workers. That device is much used in Life’s Too Short, which stars Warwick Davis as himself, a hapless little person with a modest IMDB history of bit parts in blockbusters, desperately casting around for acting work, any work, as well as coping with tax problems and an impending divorce. However, whereas in The Office, you were doubled up with laughter, with Life’s Too Short, you, too, the viewer, are stunned, mute, unsmiling. This is someone’s idea of a joke? How was this ever commissioned? Yes, we understand it’s A Ricky Gervais Production – Davis is so obviously a Gervais proxy – but beyond that, what the hell is it supposed to be?

While giving a lead to a dwarf in a high profile series is ostensibly "progressive" (and Davis doubtless, understandably, glad of the work), the comedy, which is constantly at the expense of his height, feels, well, arrested. Even in the dark, pre-political comedy days of the 70s – when Asians were considered inherently amusing, when no fat woman could enter a scene without a bassoon striking up, when a TV bulletin warning about a local rapist on the loose would see a sitting room spinster sigh and remark, "Chance would be a fine thing!" – Rudolph Walker had to pay for making a similar breakthrough to Davis’s as one of the first lead black characters in a UK sitcom (Love Thy Neighbour). His success came at the cost of him enduring the continual taunt of "nig-nog" and "sambo"; and even back then, audiences and execs would have winced at the indignities Davis undergoes for our supposed amusement. The nadir of this comes in the episode four, in which he’s locked in a bathroom because the door handle is too high, falls out of his car because his seat is too high, and can’t reach an item on a high shelf, despite his frantic clambering, because, well, the shelf is too high.

Perhaps this is some triple-axle attempt at post-post-postmodern irony, an ultra-sophisticated comedic in-joke that has tied itself up in such obscure knots it only seems crass to the un-knowing, the obtuse. Well, that’d be me because from where I’m sitting it looks like we’re supposed to be laughing at a guy for being "too" short.

What’s even more confusing is that, whereas in The Office, there was a naturalistic plausibility to the action (and inaction), the overlapping, halting dialogue and half-glances from work station to work station, that exquisitely judged sensibility seems to have drained away entirely from Gervais’s post-Office work. For a show whose surrounding tagcloud is bound to throw up the words "political correctness", the characters in Life’s Too Short are mystifyingly bereft of that quality, and all the common courtesy and sense of shame it entails.

Take the a passer by who starts videoing Davis in the street because, "you know, it’s funny, a dwarf carrying a box". (He eventually ends the scene by falling over because, HAHAHAHAHA, the step into a building is too high.) Johnny Depp unabashedly treats him like a performing circus freak, Gervais himself, as himself, refers to him as the "inch-high detective", etc. Sure, dwarves might well encounter these attitudes, but all the time, from absolutely everybody? This has no accordance to reality – rather, it’s like Gervais has tried to bake up his own Curb Your Enthusiasm, but got the ingredients all wrong.

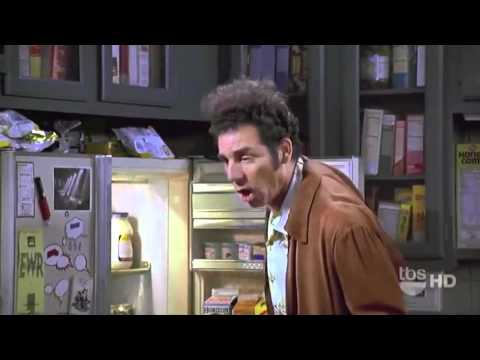

Is this the only way you can garner laughs from little people in a sitcom – constant reference to their littleness? No. Here’s an example of how it should be done. Mickey Abbott, Kramer’s occasional sidekick in Seinfeld.

It’d be wrong to suggest that Mickey’s height doesn’t in some way contribute to the comedy; there’s a tall/short thing going on, and Mickey’s volcanic irascibility comes better and funnier from a little dude. But in this clip and his appearances elsewhere in Seinfeld, the laughs come from non-height related physical business and the sheer strength of Mickey’s character, especially in cahoots with, or set off, Kramer.

In Seinfeld we trust. In Gervais, we do not. I parted company with the Karl Pilkington podcasts. For many, Pilkington’s quasi-autistically bizarre take on the world was reason enough to chuckle. But if he was a funny enough character in his own right, why on earth did he need Gervais and Stephen Merchant riding shotgun with him, constantly making with the "How mad is that?" commentary and manic guffaws? Surely it’s not for a show’s co-creator to provide all the laughter in its laugh track. Surely it’s for us, the audience, to decide how "mad", or whatever, your comedy is. Moreover, it felt like schoolboy baiting, as if Pilkington were some shambling creature with a rope round his neck, roped in to amuse the sixth formers with his hilariously untutored, eccentric utterances. (Though again, it was confusing. Is he for real? Is Pilkington Pilkington, or "Pilkington"?)

Gervais has always had a thing about "special", or "challenged" types. Here’s his Derek Noakes, from a 2000, pre-Office sketch.

This feels modern, insofar as it’s a downbeat parody of reality TV but while it’s strong on bathos, it’s utterly without pathos. The Satie music is there as a joke. We’re not meant to sympathise with this Noakes creature, or find anything noble or moving in him; he’s just a futile fucking idiot. Worryingly, that’s what we’re invited to find funny. You can too well imagine Gervais did, as he conceived him. HAHAHAHA! It’s as if there’s some residual lump of schoolboy cruelty in his soul. It’s like one of his balls never dropped.

HAHAHAHA! That laugh, see, that’s the problem. Now, Gervais is indisputably educated in comedic matters. He’s got great taste and cultivated opinions in comedy. Unlike most comedians, however, who, being so good at what they do are not easily moved to laughter, Gervais laughs with grating, high-pitched frequency. It doesn’t seem to take much to set him off his inner, giggling adolescent.

Which brings us to "Mong-gate". No need to revisit the rights or wrongs of that issue. There’s a debate to be had about context, connotations, public and private use of certain words. The problem with Gervais is that he conducted himself so shiftily and aggressively in the hoo-hah that followed, throwing out cliched, ad hoc accusations to his detractors of being "uptight" and, worst of all, referring to the "humourless PC brigade", the sort of phrase the scoundrel resorts to when even the last refuge is closed. His excessive defensiveness made him appear unengagingly boorish, and, worst of all, unsure of his own ground. Again, can we trust this man? He seems a bit . . . haywire. And a bit of a boor, and a creep, and a bully, and an oaf, too – the worst sort of boor, creep, bully and oaf, in that he knows much better than to be a boor, creep, bully and oaf.

Though, like Stewart Lee, I believe Political Correctness to be absolutely a good thing (remembering, as I do the dark days of "Chance would be a fine thing!"), comedy should naturally be fearless, nothing should be off-limits. It’s comedy’s prerogative to be transgressive. But you don’t just charge in like a Frankie Boyle into a china shop of sensitivities. For that sort of thing to work, you need to be operating from an absolutely sound and stable moral core. In other words, to do non-PC comedy, you need to be PC as fuck – the way South Park‘s Trey Parker and Matt Stone are at heart, or, as brilliantly demonstrated in this clip from Louis C.K.’s new "reality" sitcom Louie. This is how the grown-ups do it.

Talk about having your cake, eating it, sicking it up and eating it again. It runs the gamut. It’s teeteringly homophobic, hilarious, repugnant, sombre and enlightening by turns, with a punchline, delivered by the most reactionary guy in the room, that’s thoroughly earned. Louis C.K. you can trust. This is "edgy" all right, but expertly wrought, educative even. Now you know about flaming faggots, and aren’t likely to forget.

Interestingly, Gervais appears in the first series of Louie as a doctor who cracks up at his own, bad-taste AIDS jokes. Handled properly in this context, he’s funny. Gervais, of course, has been very successful in America. He straddles the Atlantic. And that, maybe, is what’s happened to Gervais. He’s been allowed to get away with slack, self-indulgent, repetitive comedy that speaks more about his hermetic social set and dubious mindset than it does to us, the audience. He gets away with it because of the Brand Recognition surrounding his name and overweening presence and, because no one at the BBC is big or bold enough to lob stuff like Life’s Too Short back at him and tell him to try harder, be better. Do that, you suspect, and it’s bye bye Ricky to America for good, where he’s more appreciated – a terrifying thought for Beeb execs.

Funny, when he was fat, Gervais’s comedy was a great deal more lean. Now that he’s gotten buff, his comedy has gone flabbily to seed. He’s been coasting, not challenging himself. If he ever wants to recapture the form of The Office, he needs to give himself a proper look in the mirror and shape up. But who’s going to make him?