Why is it not okay for a model to take fashion inspiration from the homeless and why is this even a question I’m having to ask?

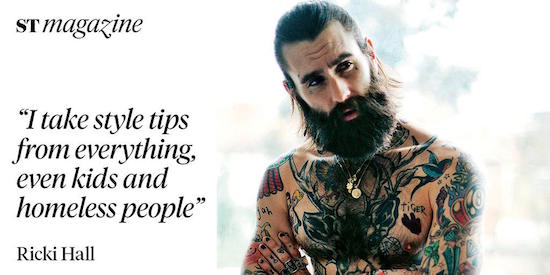

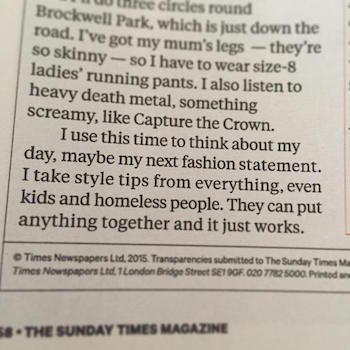

In a week of bigoted and really stupid things people said being reported on social media – and in some cases, inexplicably, by their own fair hand – people were angry on the internet again yesterday when, in a Sunday Times interview, model Ricki Hall let the world know he gets his sartorial cues from homeless people. Why? "Because they can just put anything together and it works," of course.

It’s difficult to know where to start with all the things that are wrong with this or to know for sure whether Hall is a real life Mugatu with a passion for the Derelicte (like Kanye citing the 2011 London riots as a major influence for his Adidas collection) or more like one of those other hapless handsomes in Zoolander, larking around, just minding their own business and enjoying your standard, carefree petroleum-fight until – inevitably – it literally blows up in their intolerably-smug face (and, we have to assume, scatters the vehicular and biological parts of the other patrons across the forecourt – which is the kind of collateral damage you just don’t hear about when models get together).

Yes, there are explanations more lenient towards Hall. The one which would be most likely – kindly offered up to Twitter users in an attempt to quiet the shit-storm before it reached the point of Twister-esque cyclonic cattle fly-by – was that he had been misquoted. Sure, it happens. It happens a lot. Every day, probably. What doesn’t tend to happen, though, is the victim of alleged misrepresentation immediately retweeting another user praising the interview in question for its honesty; for how "refreshing [it is] to read about someone who doesn’t bullshit in interviews".

No: someone – somewhere in that interlinked Venn diagram of questionable editorial policy, things no one with their brain switched on would possibly think it was appropriate to say to a journalist or say to anyone for that matter and people not knowing when it’s best to just shut up for Christ’s sake – is bullshitting. (NB: A second widely-touted and reasonably well-evidenced theory is that he’s just kind of a prick with the self-awareness of an infant pet rock.)

Aside from the one Hall retweeted, calling bullshit on his own calling bullshit on The Sunday Times, responses haven’t exactly been kind to the model, with Vice taking the lead (though admittedly needing little encouragement) to ask, ‘Is this guy really the worst person of all time?’ Reserved for only the highest levels of people behaving terribly in the public sphere, Get In The Sea has done its usual bang-up job dishing out the aquatic imperative (@getinthesea “IN YOU FUCKING GO, HALL”) and novelist John Niven, an early contributor to whole affair, was keen as ever to publicly disassemble the man who – if nothing else – objects to being painted as the kind of guy who uses Lynx Africa.

You could almost – well, not even nearly almost – be forgiven for thinking there were probably as many male models as rough sleepers in the UK: if you own a television, a computer of any sort or have found yourself on a street with shops in more or less any city in the last few years, chances are you’ve seen a male model. And you’ve probably also seen homeless people, too – not just the ones who ask you to buy a well-known charity magazine or spare some of that loose change you’re sorry that you’re not carrying – but also men, women and children who aren’t obviously displaced: in 2014, an estimated 2,744 people slept rough in London alone on any given night of the year (a rise of 55% in four years) and 280,000 people approached their local authority for homelessness assistance.

While there isn’t, as far as I’m aware – and, yes, I’ve looked – an official statistic for the number of people in this country currently employed as a male model, I’d wager it’s fewer than either of those two numbers. And, while the media has its part to play in that – bombarded as we are with images from the time we have trouble waking up because the bombardment of images has been so exhausting, to the time we have trouble falling asleep because the bombardment of images has been so utterly stimulating – it never hurts to actually consider the personal microclimate of privilege which facilitates that.

Unthinkingness and total disregard for/acknowledgement of privilege aside, I’m sure all those homeless people Hall scouted for hot tips are totally overjoyed to be getting a shout-out in a broadsheet newspaper which costs more than a hot drink, namechecking them as though they’re some kind of wilful subculture or, worse, like they’re a single, homogenous entity – the wider problem is a misuse of language.

The statement, teeth-grindingly ridiculous and blood-spouting-from-the-ears infuriating as it is, rests on a single word so far removed from the lexical field of marginalisation applicable to homelessness (but one linked intrinsically to the world of fashion to which Hall belongs) that it is jarring even to see them put together in that way: ‘can’.

It’s flippant and entitled terminology, and it simply doesn’t come into play for people who have been forced into a position of doing what they ‘need’ and ‘have’ to do in order to survive just to be able to do the same thing again tomorrow. The reasons for homelessness are complex and nothing like as simple as a choice people make when they wake up in the morning (“The turning points most often cited by UK male participants were relationship breakdown, substance misuse, and leaving an institution [prison, care, hospital, etc.]; while for UK women the most common were physical or mental health problems and escaping a violent relationship.”), and it sure as shit isn’t comparable to the wash-gradient or distress factor of your shitty jeans.

Karl Smith is Literary Editor of The Quietus and a freelance writer. Follow him on Twitter: @karlthomassmith