In a recent article for the online publication Real Life, the American philosopher Robin James writes about Lil Nas X’s hit ‘Old Town Road’ as a peak example of a 21st century pop song’s "remixability", or its cultural sturdiness and formal adaptability – in James’ words, "how open a song is to being iteratively reworked, meme-style, without becoming substantially different."

Songs that demonstrate a capacity for remixes, reworkings and cover versions tend to succeed more in today’s music marketplace, James argues, "if an original release is adaptable enough to transgress boundaries between things like genres or demographics." Capitalism loves reiterations, sequels, and franchises, because they at once expand upon a cultural form’s capacity for generating profit while simultaneously cross-pollinating diverse audiences, transcending barriers like age, race, class, and aesthetic taste.

Yet soft-drink jingles mastered this mimetic style of remixability far before Lil Nas X, internet memes, or Instagram. In the twentieth century, commercial jingles were the most innovative form of advertising, pairing a product with an icon of popular culture. What Coca-Cola introduced was the concept of adapting their jingles to as many musicians as possible. Coke even released a record of these various iterations in 1966, and the corporate jingle became a mainstay on radio, television, and in film for decades afterwards. There is something charming about these jingles in the way that there is something charming about folk songs and songbook standards. There’s something to the idea of music as an exercise. But when money manipulates and moderates and modulates those exercises, they don’t strengthen the art. Instead, they weaken the entire artform.

The young crooner and heartthrob Bobby Curtola was a cultural icon and teen idol in 1960s Canada. His smash songs ‘Fortune Teller’ and ‘Hand in Hand With You’ helped make him a local household name, sold multiple millions of copies, and vaulted the Ontario native to international stardom. But in 1964, Curtola had an unusual hit. The song was called ‘Things Go Better With Coca-Cola’, and it was unusual because it was both a commercial song and a song commercial. "Life is much more fun when you’re refreshed," Curtola chirps, "and Coke refreshes you best."

Even though the company had a half-century long history of corralling star celebrities to endorse its product, beginning in 1900 with the cabaret singer Hilda Clark, Coca-Cola and Bobby Curtola’s connection marked a pivotal shift, the very moment at which the popular music recording and soft-drink industries indelibly entered into an uneasy alliance. Curtola’s original version acts as a kind of skeleton upon which the substance of different artists’ styles can be globed on, like a musical Frankenstein monster. Among the artists to record Curtola’s song were Roy Orbison, Otis Redding, and The Supremes, and they each brought their signature sound, and spoke to widely diverse audiences.

The Roy Orbison version, for instance, frames Coke as central to the break-up-make-up cycle of heteronormative romantic relationships: "Let’s talk again, let’s joke again, let’s get together for a Coke again." Here, the product is entwined with a heartbreaking narrative of love, nostalgia, and the ultimate comfort and joy of reuniting with a lost mate. And the theme of "reliving" – i.e. reiterating – seems consciously pushed to the fore in Orbison’s recreation.

The Otis Redding version appeals to audiences of colour and focusses acutely upon the "things" that go better with Coke. Coke after Coke after Coke. The Supremes version rings with the MoTown Wall of Sound aesthetic and appeals more to younger and female audiences. Unlike the melancholy of the Orbison and Redding versions, the Supremes’ iteration is effervescent, mentioning music, dancing, and the beverage’s tingling bubbles. And both Redding’s and the Supremes versions have prominent horn sections making for altogether hornier dubs of the jingle, trading directly in hypersexualised, racist stereotypes.

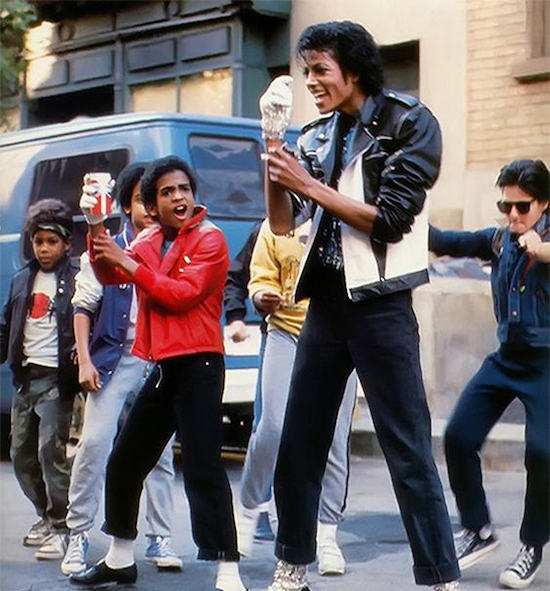

Speaking of hypersexual, in the famous 1984 Pepsi ad featuring Michael Jackson, you might recognise a young Alfonso Ribeiro, who would go on to play Carlton Banks on 147 episodes of the American sitcom Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air. This advert highlights how kids – and particularly black kids – are targeted, recruited, and objectified by soft drink companies. The Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity at the University of Connecticut recently found that black children were almost twice as likely to view TV ads for soft drinks than their white neighbours.

Tobacco and alcohol have age restrictions on the purchase of their products, and their marketing since the 1990s has been heavily regulated and scrutinised to ensure that it doesn’t engage minors. Soft drinks, however, exhibit the very essence of predatory behaviour. Reach them while they’re young, addict them to sugar, caffeine, addict them to addiction itself, addict them for life. Both music and soft drinks ultimately encourage addictive behaviours, stimulating the brain’s pleasure centers by releasing dopamine and serotonin into the bloodstream. "Music is my drug" and "sugar is my drug" are both true statements, not mere hyperbole.

In 2016, after a particularly uneasy night at a Red Bull Music Academy-sponsored event in Montreal, I came home at once exhausted and fully charged. Some of my favourite local musicians, among them Tim Hecker, Kara-Lis Coverdale, and Alex Moskos, had played a seemingly very high production value gig in an abandoned warehouse that I had walked by hundreds of times but never truly considered. Indeed, the entire neighbourhood was once mostly empty. Gentrification in Griffintown, Montreal, was well underway, though, and condos were sprouting up quickly. I had seen not only empty warehouses retrofitted into swanky and expensive digs; developers were after residential properties, too. One, just up the street from my house, a three-story brick building built in 1900 and containing ten low-rent apartments and a corner store (in Quebec we call them "dépanneurs", or "deps") had burnt down under suspicious circumstances. A new condo development now stands on that spot. The dep is gone, and the condos, some AirBnb’s going for several hundred dollars a night, are anything but low rent. Somehow, I couldn’t help but see the Red Bull event as part of this process – as a gentrifier of entire scenes, entire communities.

I had remembered the media critic Rob Walker’s book, Buying In, which I would immediately dig up and reread. I’d recalled that it contained a lengthy segment critical of Red Bull’s unorthodox promotional campaigns. Red Bull was leading the soft drink industry when it came to inventing innovative and exciting marketing strategies, carefully constructing itself as an edgy, hip, street-wise brand. They accomplished this by deliberately avoiding old-fashioned promotional strategies. This meant experimenting with non-traditional concepts: for instance, hiring everyday people as "brand evangelists" to help build "grassroots" word-of-mouth campaigns. Or especially by sponsoring outsider activities. That is how Red Bull became involved with extreme sporting events.

Red Bull was the major benefactor of a catamaran team that illegally crossed the ninety-mile corridor from Key West to Cuba. Throughout the US, they held breakdancing competitions called "Red Bull Lords of the Floor" and distributed free Red Bull at high-profile video game tournaments. But their masterstroke of micro-targeting the so-called "unreachables" – the emerging, tech-savvy, and highly profitable millennial generation of consumers that most industries regarded as beyond the grasp of conventional advertising – was Red Bull Music. "The company picks a dozen or so cool young people in several cities," Walker described in 2008, "and enrols them in a free multiday workshop where they learn how to create original music using the latest electronic technology."

Many of us are likely familiar with the Red Bull Music Academy story, and what happened next. But for a moment, it seemed brilliant, a major advertising coup. Red Bull never commissioned a musician to sing a Red Bull jingle or contracted an artist to be their celebrity spokesperson. Instead, they devised insidious ways to harness themselves to grassroots communities that were already in full trot, infiltrating music scenes like a virus instead of simply co-opting them. Rather than the brand being dropped into the music, the music was dropped into the brand. For the following decade, Red Bull would deploy with evolving precision the strategy that Rob Walker termed "murketing" – blurring the boundaries between what we buy and who we are – to simultaneously cement their own brand identity and, in the process, nurture one of the most radical musical ecosystems of the early 21st century.

"Capitalism’s top brand names – Coca-Cola, Google, Starbucks – have attained an asignifying abstraction," wrote Mark Fisher in his essay Atwood’s Anti-Capitalism, "in which any reference to what the corporation does is merely vestigial. Capitalist semiotics echo capital’s own tendency towards ever-increasing abstraction." What a company actually does – the products it manufactures and markets; the services it delivers – is deliberately diffuse and indeterminate in the 21st century. Red Bull Music Academy in particular relied upon vast new infrastructural vistas: a flailing music industry, the internet and emerging social media, cutting-edge digital music technology, avant-garde fashion and body modification, mobile wireless communication, &c.

Slavoj Žižek in his 2012 film The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology reminds us: "It was already Marx who long ago emphasized that a commodity is never just a simple object that we buy and consume. A commodity is an object full of theological, even metaphysical niceties. Its presence always reflects an invisible transcendence." Think of the taglines: "Coke is it." "Coke is the real thing." "The joy of Pepsi." "Red Bull gives you wings." Red Bull’s slogan explicitly renders the promise of transcendence visible, even tangible.

Žižek continues: "In our post-modern societies, we are obliged to enjoy. Enjoyment becomes a kind of a weird, perverted duty." Music events implore us to participate in part because of their extraordinary ephemerality – their event-ness – and in part because we feel obliged to have fun. Concerts and festivals, like the one RBMA staged in my neighbourhood, exist for our total, hypnotic enjoyment, for the abandon of workaday realities, the corporeal and physical limits of capital that confine and restrict us. The festival is an emotional release valve of sorts. It makes capitalism acceptable – even preferable – to its alternative, in which there is always the possibility that there may be no festival. The festival provides us with a safe and regular time and place for reckless delight, so that we can again unproblematically and immediately resume upholding the dominant social order.

The festival’s setting – the smoke, the lighting, the mise-en-scène – is all designed to immerse our senses. But none is as visceral as the music’s sheer volume. At Red Bull’s festivities, there is no sense, indeed no atom of one’s being, that is not bombarded, assaulted with sound. Writing on loudness, the post-modernist theorist Paul Mann noted in his 1995 essay Stupid Undergrounds: "There is, in a certain sense, no difference, no line between sound so loud it is all one can hear and sound so deep and pervasive it cannot be heard at all."

Where once festivals might have served as modes of community-building, social cohesion, and solidarity, they are now feats of endurance, an obligatory energy drain. Volume can be read in a double sense: loudness, but also overabundance. Red Bull Music Academy’s twelve-hour-long Griffintown event in 2016 was dubbed Drone Activity, ostensibly an acrostic wordplay on military drones and the drone music genre, but also a tacit admission that the company’s goal was to facilitate mindless, repetitive, predictable, and most importantly profitable action. "Our event series," Red Bull’s website proclaims, "[brings] together the most intense music in the world." It is during these intense, emotional, and profoundly affective events that brands have sneaked into our most vulnerable states, the very moment which Žižek describes as "idiotic enjoyment" – that rare and particular period when "even totalitarian manipulation cannot reach us." But brands have found a way in.

The world is now undergoing an awakening that at times seems painfully slow, and at others appears to run away from us. Every day, more and more people are making the connections between capitalism and climate change, between capitalism and poor physical and mental health – ultimately, between capitalism and falsity. This story has been told many times before: industry X produces product Y; truth about product Y jeopardises profit; industry X obscures truth. These processes are happening on a global scale and are so entwined within industry and culture as to seem inextricable. Nevertheless, we must at least attempt to tell the truths as we see them about our own experiences and areas of expertise. We have to try and loosen the knots of capital from binding everything to it and sinking the whole ship.

Global water security is the most urgent concern we face. The World Economic Forum, the influential Swiss-based foundation, warns that water crises will become "the biggest threat facing the planet over the next decade." Water is the source of all life. Any and all industries that turn water into an unhealthy product and trademark it for human consumption and corporate profit must be held accountable. Similarly, sugar is one of the gravest threats to human health in the 21st century, and the fight against the global sugar industry is tantamount to the 20th century fight against big tobacco. Countless clinical studies have linked early age consumption of soft drinks with childhood obesity and type-2 diabetes, among other serious ailments. According to the health and science journalist Gary Taubes, author of The Case Against Sugar, sugars "have unique physiological, metabolic, and endocrinological (i.e. hormonal) effects in the human body that directly trigger (diabetes and obesity)." Add to this caffeine, Taurine, aspartame, and other artificial, complex, and highly processed chemical compounds, and we begin to understand why soft drinks can pose significant health risks, and consumption habits that mimic addiction.

We no longer recognise brands and commodities as socially constructed, so we want to oversimplify and assign agency to them – agency that is really much more chaotically distributed, structurally prescribed, and historically driven. We tend to say, for instance, that the Walkman changed how we listen to music, rather than saying that home electronics companies changed how we listen to music, or the desire for portable listening devices changed how we listen to music, or an influx of inexpensive Japanese consumer goods into the malls of America changed how we listen to music – all of which are also true.

The mythologizing statements that Red Bull Music Academy made this spring in the days following the announcement of its dissolution – that it was much more than another round of job losses, that RBMA was a benevolent patron of non-commercial art forms – endowed its operations with immense influence and undue magnanimity. The creative activity that occurred under RBMA’s watch was doubtless significant. But attributing these kinds of immense cultural movements to the purview of products rather than their vast social and industrial dimensions, ascribing them near-mystical abilities to affect real-world changes of enormous magnitude, is the very definition of commodity fetishism. This misidentification of power has disastrous consequences: the subject’s alienation; the transference of fear and desire to things rather than people; and ultimately, the determinist air of it all. As Robin James wrote, "When building capacity and the pleasure in doing so is experienced neither for its own sake nor our own sakes but for the sake of generating profits for the wealthy, the pleasure we feel in resiliently overcoming our prior limitations merely masks our subjection."

What’s at stake here is bigger than one’s opinion of whether or not an artist is selling out by singing a jingle or performing at a corporate-sponsored festival. It is about nothing less than the viability of future life on this planet, and we now have to forge a new path between taking individual responsibility for our choices and pushing for policy changes from industry and governments.

Because its inner workings are concealed, capitalism appears fateful to us, and every one of our decisions is reduced to some degree of sneering forfeiture. Underground artists especially have been forced into a corner, forced to compromise the very ideals that make independent artists independent. Imagining a world beyond this despair means grasping the complex totality of social labour and our potential roles in it, reclaiming agency away from corporations and industries, no matter how full of fizz the deal might seem on the surface, and charting a new course that better benefits all of us.

This article is a version of a talk given at this year’s Unsound Festival in Krakow. The author gratefully acknowledges the support of Unsound, the Municipality of Kraków and Kraków Festival Office in producing this work.