Another US election cycle, another spike in global tear-gas consumption. It was hard, watching the coverage of protesters at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions being brutalised, beaten, and arrested by masked and armoured cops, to resist a feeling of, well… nostalgia. For in 2008, there’s something inescapably quaint about the idea – whether propounded by the protestors themselves, or those whose activities they are protesting – that chanting, singing crowds pose such a serious threat to the status quo as to warrant such repressive measures.

It was not, assuredly, always thus. The disturbances outside the Democratic get-together may have been decidedly lower-key than their Republican equivalents, but the rubric under which many of them were (dis)organised expressed an explicit and elegiac yearning for a time when such protests could and did alter the course of political events. "Recreate ‘68" was the central theme for the ruckus; and its meaning was unmistakeable.

Unmistakeable, and not a little baffling; following a legendary free public performance by the MC5, the riots at the 1968 DNC in Chicago saw protestors clash all week with police. Over 1,000 people were injured, a HUAC hearing was eventually convened to investigate the organisers, and the disturbances were widely credited with helping Richard Outhous Nixon to his narrow election victory. Not, you would think, a result anybody but the fringiest of the fringe would hope to replicate.

How long ago 2000 feels, in that respect at least. Risible as it might seem now, there was a widespread feeling that no significant difference existed between the platforms of Al Gore and George W Bush, that both stood in more-or-less equal measure for Big Business, environmental pillaging, rapacious imperialism, and tax cuts for the rich. The only "real" left-wing alternative in the election, it seemed. I was among the protestors outside the DNC in L.A. that summer, as Al Gore secured the Democrats’ nomination and, while it would be a decided exaggeration to say we would gladly have cost him the election, it is hard to imagine many of us would have shed many tears at the thought we might do so. After all, a Bush presidency would be no worse than a Gore presidency, right? Ah, the folly of youth!

If those protests are remembered today (…and if they are of interest to Quietus readers…), it is for what took place on the opening night, Monday 14th August. Somewhere inside, Bill Clinton was speaking. Outside, Rage Against The Machine were headlining a free protest concert. And that’s pretty much the last thing that night that anybody agrees on.

The confusion and contradiction of what happened was nicely captured in the following day’s LA Times, where a picture of clouds of gas billowing over the crowd was juxtaposed with the headline "LAPD Refuse To Confirm Tear-Gas Used On Protestors". The incident would become known as The Battle of Los Angeles, after Rage’s then-current album. Indeed, many people will swear blind that the album was named after the riot; a spectacular feat of prescience if true, given that it was released in 1999. As far as the popular image goes, Rage Against The Machine played outside the DNC, while cops beat and gassed their fans.

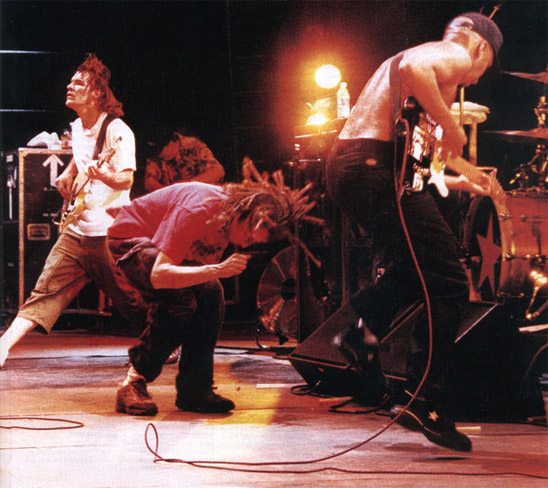

In fact, Rage weren’t even playing when things kicked off. Absolutely not. Believe me, I was there. They had played earlier in the afternoon, which rumour had it was to avoid being shut down by The Cops. They put in a truly shitkicking performance, loud and extremely pissed-off. Zack told the crowd they had a solemn duty "to oppose these motherfuckers", before unveiling a then-new cover of the MC5’s ‘Kick Out The Jams’ – the inspiration of Chicago ’68 could scarcely have been more explicit. The afternoon was sweltering, and the crowd was beginning to seethe with anger, aggression, and some drunkenness.

It was after Rage, during Ozomatli’s set, that everything boiled over. A group of the ubiquitous "Black Bloc"ers, soi-disant anarchists clad in facemasks and the eponymous anti-uniform, had – not for the first time that week – begun to use the shelter of the crowd to antagonise a leaden-handed police force who were, quite visibly, looking for any excuse. As though screaming "Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me" in frustrated, impotent rebellion against the biggest, baddest parent-figure of all, the anonymous strop-artists began throwing whatever projectiles came to hand over the fences at the massed ranks of riot cops; stones, coins, even bottles of piss. The response was every bit as predictable as it was disproportionate.

At this point, the police cut the sound from the stage. That much is clear, though it was hard to make out what happened next, in the ensuing chaos. The police claimed they gave the crowd fifteen minutes to disperse, using megaphones, and there’s no particular reason to doubt this. But this was a crowd of 15,000 or so people, at an open air rock concert, in a barricade-lined square. It took a long, long time for word even to filter through to those near the exits, let alone for a congregation united in its distrust of authority to get moving, and by the time we did, the LAPD had lost patience. They started the attack with teargas; protecting ourselves with bandanas and kerchiefs, toothpaste under the eyes and slices of lemon to suck on, we were prepared but comically outgunned.

Then the baton rounds began. Rubber bullets are supposed to be "safe", in the sense that they are non-penetrating, non-lethal. But they are solid and heavy objects, fired at high velocity, and they have the same effect on the victim as, well, being struck with a truncheon. Shoot one at someone’s temple from sufficiently close range, and you’re very likely going to have a corpse on your hands. Originally designed to be fired at the ground so they would decelerate and bounce into the legs of rioters, they carry a mandatory minimum safety range so that their velocity can drop sufficiently before impact to avoid maiming or killing; the Israeli Defense Forces consider their use within 40m of the target to be strictly illegal, but most democracies insist on fifty. I cannot say with any precision just how close the LAPD were when they shot at us, but I helped carry away one schoolteacher whose badly-bruised and probably-broken leg also bore burn marks. They were, he explained to the first aid team, powder burns from the rifle.

That is not, to say the least, the typical 2008 gig experience. But it’s worth thinking for a bit about why that is. As the Recreate ’68 folks know, and as Zack De La Rocha was surely aware in invoking the MC5, there was a time when rock music genuinely did seem a threat, on some level, to the political establishment; and that threat peaked, just about exactly, forty years ago. Political violence was endemic; riots engulfed university campuses across Europe, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King – always a far more radical figure than contemporary hagiography is apt to remind us – were assassinated, and the US was in the grip of a violent cultural conflict from which it has arguably never recovered. The nostalgia industry reminds us of the "summer of love" in 1967, but it was very quickly supplanted by an altogether different mood; by 1968 the prospect of universal brotherly love had receded, amphetamine consumption was far outstripping that of LSD, and the mainstream and "counterculture" faced off against each other with mounting distrust and violent tension. Revolutionary, even terrorist figures like Black Panther Bobby Seale, Yippies Abbie Hoffmann and Jerry Rubin and – remember this one, if you think the scars of the era have fully healed – Bill Ayers of the Weather Underground, were central to both the message and milieu of the era’s rock music.

It’s hard to imagine now just how deadly serious The Rolling Stones’ ‘Street Fighting Man’ must have sounded back then. "Fighting in the street, My name is called Disturbance…" The Stones still tour, of course, but these days when Mick Jagger hears the sound of a thousand marching feet, they’re as likely as not on their way to the champagne bar. And that change is instructive. It’s true that the massed ranks of the Slebs still support the nominally left-wing alternative as a matter of course (for a particularly gruesome illustration, see Dave Stewart’s recent ‘American Prayer’ video for Barack Obama). But "support" in that context has come to mean Bono posing with the Pope, or Chris Martin scrawling things on his hand like a particularly precious fourteen year-old. It’s difficult to imagine either of them toting machine-guns on stage, or calling for blood in the streets.

The problem, if one may wax inappropriately pretentious for a moment, is that the symbols of what used to seem genuinely a counterculture, a transgressive and oppositional riposte to the culture of the political and social mainstream, have been co-opted by that mainstream. The symbols remain, but nothing of substance now underwrites them, and we are left with an empty semiotics of radicalism. Bobby Gillespie may bang on about the Black Panthers and the MC5 at every opportunity, but he had meekly renamed ‘Bomb the Pentagon’ by the beginning of October 2001.

As Rage Against The Machine once again hit the summer festival circuit this year, even scheduling their appearances to free up time to provoke another near-riot outside the Republican National Convention in Minneapolis-St. Paul, it’s worth asking whether all this goes for them too, whether they are mere poseurs or, perhaps worse, a genuine anachronism.

Probably, they were an anachronism even in 2000. The nature of a capitalist system is to appropriate its opposition, to absorb the symbols of dissent, and repackage them as part of the whole; anti-capitalism itself becomes a marketing ploy within the capitalist whole. It was swiftly forgotten at the time, but overlooking the "designated protest area" where Rage played in LA eight years ago, was a six-storey billboard, emblazoned with the images of John Lennon, Martin Luther King, and MK Gandhi, and advertising Apple’s new iMac. Since then, even Kicking Out The Jams has been co-opted, as pretty young things sport artfully distressed MC5 t-shirts on red carpets and catwalks everywhere; the Revolution brand, it seems, will be mass-marketed. Whatever you may think of Rage Against The Machine’s music, or their politics, they’re a reminder that there was a time when rock – mainstream rock – was properly dangerous, a genuine rejection of, if never in truth a serious threat to, the status quo. And the more rock music is taken over by the very social forces whose overthrow it once seemed to seek, the more Brit School graduates and warbling squaddies clog up our airwaves, the more the likes of Ticketmaster and Carling tighten their grip on the very geography of what still purports to be a mode of dissent, the more relevant, the more essential, Rage remain. It’s good to have them back.