A new kind of music is sweeping the nation’s youth. Its sound is deliberately alien and incomprehensible to outsiders. Fans are immediately recognisable on the streets from the strict (if largely unspoken) dress codes associated with the genre. Its aesthetic tenets have even spread beyond music, into the other arts. Certain forms of street art, of short film-making and spoken word performance, may even have claim to precedence over the music, in what should probably be regarded more as a rising movement than mere generic tag. Manifestos are being written. Already schisms and expulsions are creating divisions and highly-contested dissident factions which play out their feuds in an active samizdat press of Tumblr blogs and cheap xeroxed zines. To stumble across these communities – on the web, at a gig, or on the street – is to enter a world complete unto itself.

None of this is really true, of course. And if it were, it might seem faintly ridiculous – somewhat terrifying, even. But by presenting this set of fictions together like this, I hoped to draw attention to something that we might regard as missing (or perhaps simply less visible) from our culture over the last quarter century. For somewhere in that first paragraph – give or take the odd clause, substitute the odd predicate – we can recognise many of the artistic movements through which the story of 20th century culture is now commonly told: futurism, Dada, surrealism, beatnik, punk, hip hop, etc. And also: socialist realism [sotsrealism]. This last is key, because it is in large part due to the spectre of communism – and of communist theories of art – that today we are so suspicious of the totalising impulse in cultural movements.

A few weeks ago, I attended a talk entitled ‘Dreaming The Lost Collective’ at the Calvert 22 gallery in London. The talk was given by Agata Pyzik, author of a new book called Poor But Sexy: Culture Clashes In Europe East And West, in conversation with Professor David Crowley from the Royal College of Art. In amongst various discussions of old Polish fashion magazines and the historical context of recent events in the Ukraine, one statement in particular caught my attention. The year 1989, Pyzik said, signified not just the end of the USSR, but the "end of totality". Since that date, all talk of totality in art and culture, she claimed, has become "deeply unfashionable" in east and west alike.

In her book, Pyzik raises the possibility of a "theoretical redemption" of the much-derided school of socialist realism. "The greatest success of postmodernism," she writes, "is that we still behave as if we don’t believe what’s going on." In 1979, as the left lay in tatters after the descent into stagnation of the USSR and the successive defeats of May 68 and Italian workerist movements, Jean-François Lyotard announced the new "incredulity" towards grand narratives. But where does one go when the mantra of pluralism and official cynicism leads to the dead end of moral relativism – when all that is left is this generalised incredulity towards all narratives, large and small? While the old, abstract avant-gardes of the twentieth century are now officially canonised, it is – perversely – the state art, those vast canvases of party chiefs and "workers like gods", that retain the seductive whiff of the forbidden.

As Pyzik reminds us, there was always more to sotsrealism than this anyway. The ghosts of surrealism, expressionism, and constructivism could never be fully exorcised – rather they were harnessed towards a new kind of collective style. "Individual talent ceased to have any importance," she says. "What was important, at least in intention, was how art will transform their lives … sotsrealism was supposed to encompass the totality of human life."

This relates to something Johannes Kriedler said the other day, in conversation with the critic Adam Harper at the London Contemporary Music Festival. I can’t separate the music I write from the rest of everyday life, the young German composer insisted, because "they are all on the same desk". By which he meant that the bills, the letters from the bank or from his landlord, inevitably encroach upon the space in which he is writing notes on a sheet of staves, precisely because it’s the same physical space.

In the past Kriedler has made music using sonifications of stock market reports from the run up to the crash of 2008. He has also fulfilled composition commissions by outsourcing his musical labour to cheap Asian workers, hiring them to plagiarise his previous work. Repeatedly his works reach out beyond just music to a whole multimedia world from which politics – and the intrusion of some real beyond representation – is inextricable. His statement about all these concerns intruding across the physical space of his work desk reminded me of Pyzik’s reflections on sotsrealism. But it also reminded me of something James Bridle said to me last year about William Gibson’s writing.

Gibson has spoken in the past about how he tends to write with "Word open on top of Firefox", constantly Googling everything that goes into his novels and letting the online world slip from one window on his computer screen to another, infecting the narrative world of his story. In a way you can see this is in his recent books, in the way they tend to wander down the same kind of rabbit holes, chasing odd loose ends and cultural minutiae, something we’re all familiar with from using the internet on a daily basis.

This becomes particularly acute in his last book Zero History where these flying penguin-shaped drone balloons seem to have been almost literally copied and pasted from the manufacturer’s YouTube channel into the text. Bridle calls this ‘network realism’. "Fictions that are built upon or within other fictions," was how he put it to me via Skype last year; a case of authors, like Gibson, who are "so well connected [that their work] appears like science fiction to most of us, even though they are in fact contemporaneous."

The role of the internet in all this is paradoxical: a hyperstitious virtual world which produces a new form of realism, the fastest means of connecting people ever invented which has the effect of splintering culture endlessly into myriad tiny microclusters. It has become almost a cliché of music journalism over the last few years to blame the internet for a supposedly endless proliferation of micro-genres, but as Adam Harper noted in a 2012 essay for Dummy magazine, it’s equally symptomatic of the present century for commentators to feign cynicism towards each new identifying tag.

Harper mounts a spirited defence of the "fluid and subtle" genre landscape of the past decade as a potentially liberating "democratic music-making project that many hands (musicians and listeners) build and change dynamically." But Harper is also aware of the potential pitfalls in terms of "rigidity and imprisonment" that come with "slapping labels on things as if we’ve got the measure of them."

If the online environment comes across as flexible and liberating to consumers, to marketing people it can be a tremendous tool for the imposition of ever-tighter cages. Perhaps the clearest example of the way genre works in the 21st century is less the ecstatic neologising of Bandcamp hashtags than the 76,897 cross-referenced and personalised microgenres employed by Netflix to segment and predict its userbase. None of which, I think we can safely assume, are likely to have the all-encompassing cultural impact of punk or hip hop.

Today punk is celebrated as much for its visual artists (such as Linder and Jamie Reid), its film-makers (Derek Jarman, Don Letts), or its fashion designers (Malcolm McLaren, Vivienne Westwood) as for its music. While hip hop was giving the world Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, it was also throwing up Futura 2000, Jean-Michel Basquiat and b-boy dancers like Louis Angel Matteo and the Rock Steady Crew.

Partly this may be to do with physical presence. It’s much harder to compartmentalise one single aspect of a person or group of people when you have to deal with them face-to-face. Like Kreidler’s desk, rap, turntablism, graffiti, and breakdancing became enmeshed because they all occupied the same space. But youth subcultures are about more than just being together and sharing interests; they’re about imagining and enacting another world and another way of living. To think of it in these terms is already to join the activities of urban youths to a centuries-long tradition of utopian thinking.

Perhaps the clearest example of this link was rave. Few could resist the conclusion that rave was about a whole way of life and not just a particular form of music when that lifestyle was abruptly rendered illegal by the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. Much of the creativity that spurred the direct action and new social movements of the 1990s came from people who found themselves thrust forcibly into political activism by the provisions of that bill.

Twenty years later, the rave movement looks like the last of its kind – the last musical genre to which we might meaningfully even apply the word ‘movement’. For in between the second summer of love in 1988 and the passing of the Act in 1994, the world itself had moved in two significant directions.

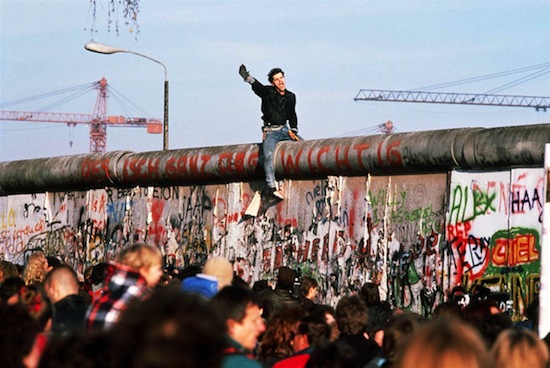

On the 9th of March 1989, Tim Berners-Lee drafted his first rough proposal for what would one day be known as the World Wide Web. On the same day, 300 people were detained after protests in the Ukrainian city of Lviv. Three days later, further mass demonstrations broke out in Hungary. Within just a few weeks, round table talks in Hungary and Poland were setting the stage for multiparty elections. By the 12th of November, when Berners-Lee and Robert Caillau published their formal proposal naming for the first time the "WorldWideWeb", the Berlin Wall was open and the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia was about to erupt. By the end of August 1991, when the Web was made public, communist rule in the Soviet Union was effectively over.

There’s obviously no relationship of causality between the birth of the Web and the fall of communism (although if the latter had happened any later you can bet people would have attributed it to the former), but their coincidence makes some of their effects hard to disentangle. Francis Fukuyama watched the Berlin Wall fall down and saw the End of History. Since then, many engaged in digital archiving have voiced similar fears apropos the instability of digital formats and the difficulty of maintaining a proper public record when everything takes place online. Likewise, the failure of communism in the eastern bloc may have engendered a suspicion towards grand, totalising projects, but big data and web 2.0 made fragmentation a reality – and a profitable one at that.

But one genre of music still maintains the will to encompass the whole of life, to include all forms of art at once and to unite them in the service of constructing new worlds. That genre is opera.