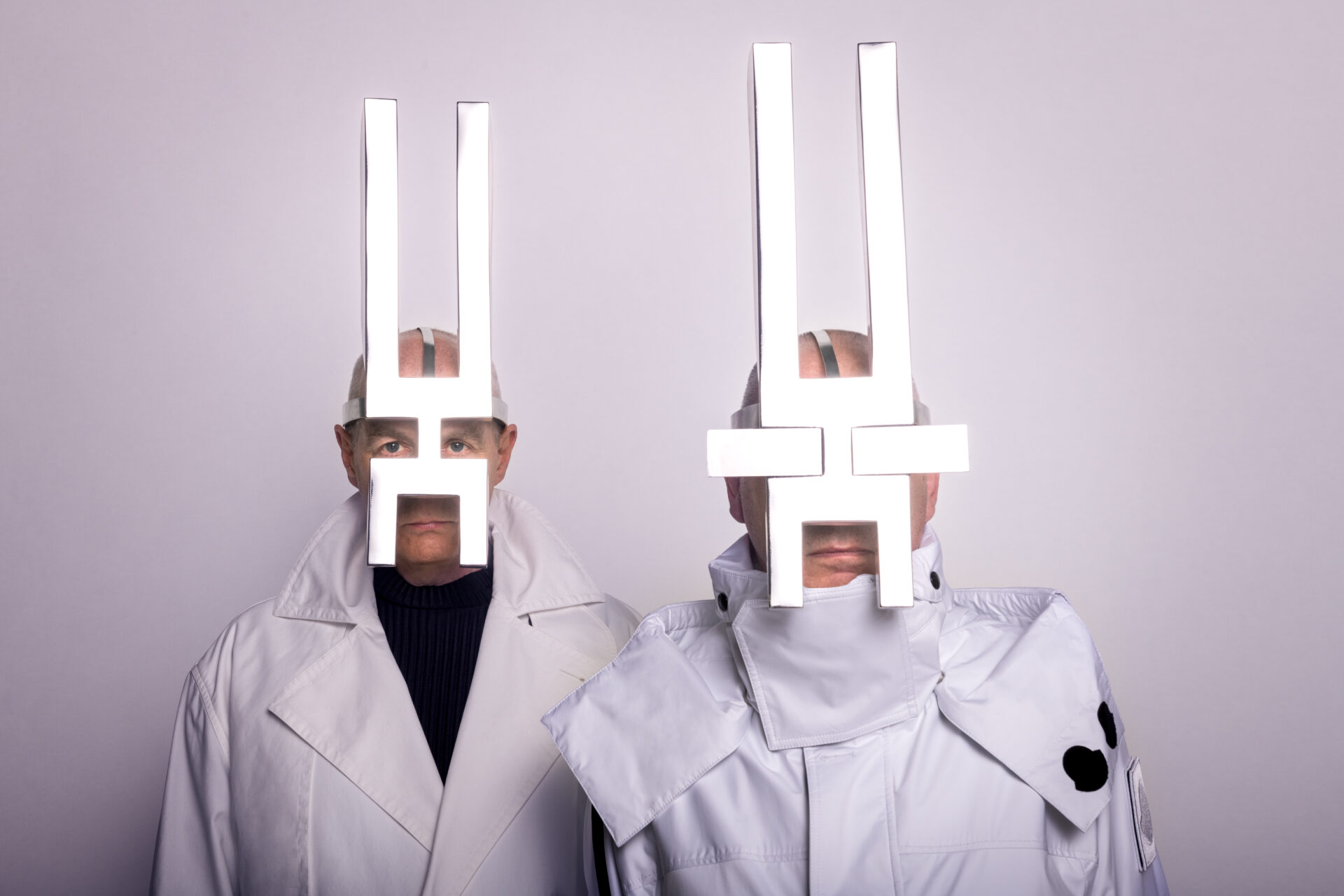

During the publicity blitz marking the release of their 15th album, Nonetheless, Pet Shop Boys appeared on Lauren Laverne’s BBC 6 Music show, unveiling their ‘Desert Island Disco’ picks – a varied selection that included Underworld’s ‘Born Slippy’, Madonna’s ‘Borderline’, and a trio of classic disco songs. It was a neat reminder of Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe’s close ties to club culture, and in a wider context, the knotty and frequently under-explored relationship between pop and electronic dance music over the last half-century.

That the Pet Shop Boys’ easily identifiable brand of emotive synth pop is rooted in dance music culture is of course well-known – the ‘dance pop’ descriptor could easily have been created with them in mind – but detailed discussion of the specifics of this relationship is often omitted from the discourse.

The recently published The Pet Shop Boys And The Political, a fine collection of academic essays edited by Bodie A. Ashton, naturally analyses their work through lenses of queerness, identity, politics and history, but Tennant and Lowe’s back-and-forth with both marginalised and mainstream dancefloors – a through-thread from 1984 to the present day – is a glaring omission.

While you’d expect this from pop, rock and general culture journalists, who either lack specialist dance music knowledge or are more drawn to the pair’s pop artistry, it’s a little more surprising from academics. After all, nightclubs can be refuges where outsider identities are formed and expressed, with LGBTQ clubs doubling up as safe spaces where the community can celebrate itself on its own terms. These clubs have also fostered significant, community-generated sub-genres that have subsequently become part of dance music’s mainstream, and ultimately pop music itself.

With its focus on songs, rather than the style of musical backing used to deliver them, pop has always been a slippery style to define. Like dance music, pop lives in the moment, riding cultural currents that emerged in the underground before redefining them. At various times in the 60s and 70s, that meant cheery singalongs with a Mersey beat, rushing Motown soul, or the triple-time stomp of glam rock. Then it was disco, a style born not in grassroots gig venues but the studios and nightclubs of Philadelphia and New York.

Ever since, pop has been in thrall to dance music, tracking the near irresistible rise of a standalone culture that has gone from being the preserve of marginalised communities to an established branch of the entertainment industry. “Dance music is a genre nowadays: it wasn’t back then,” Tennant commented during a dance music-focused interview in fan publication Annually 2022. “In Trevor Horn’s definition of a pop record, it’s a memorable song with the latest dance beat.”

Since 1984, no single pop act – with the notable exception of Madonna, the only artist to secure more Billboard Dance Chart hits – has done more to prove this assertion true than the Pet Shop Boys. But they are not alone. Over the course of their career, the relationship between pop music and dance music has become closer than ever, with even traditional singer-songwriter style artists, such as Ed Sheeran, dipping their toes into the rhythms, riffs and lead lines more readily associated with the dancefloor.

At the same time, dance music has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry with ‘emerging markets’ all over the world and a top tier of DJs, producers and artists whose stadium-sized shows put them up there with traditional rock stars of old in terms of production values and pulling power. Not bad for a style that, for much of the 1980s and early 1990s, was routinely dismissed by music journalists – like pop – as lacking in authenticity (a charge that initially fuelled Tennant and Lowe’s famous opposition to rock).

Pet Shop Boys were, and to a lesser degree remain, trailblazers – even more so than Madonna. Tennant and Lowe’s longevity, coupled with a near continual immersion in marginal and underground club culture, is genuinely unique. Through their catalogue and career, we can chart significant shifts within dance music culture, as well as moments where pop – and their music in particular – captured the cultural zeitgeist.

It seems fitting, given the matter in hand, that Pet Shop Boys’ debut record foretold the future. When Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe jetted to New York to record a low-budget dance track with Bobby Orlando in the autumn of 1983, what they had in mind was a throbbing, arpeggio-driven Hi-NRG workout of the sort he’d made for Divine and the Flirts – records that sold in limited quantities but were hugely popular within the underground gay clubs of NYC, San Francisco and London.

Instead, they made ‘West End Girls’, a moody electro number that sounded like Grandmaster Flash And The Furious Five’s ‘The Message’ with an English accent. 40 years on, the two musical movements represented in the record – hip hop and dance music – have become the dominant forces within pop.

That Tennant and Lowe wanted to record with Orlando is no surprise. Unusually for the time, they were club kids who loved disco – then deeply unfashionable following the notoriously homophobic ‘disco sucks’ movement in the United States – and were particularly inspired by new forms of electronic dance music, styles rooted in LGBTQ, Black and Hispanic clubs. By and large, these were presented as songs for the dancefloor, often initially created as extended club workouts rather than radio-friendly edits and sold as 12” singles.

Tennant and Lowe’s initial desire was to make ‘disco’ records like this – and specifically a 12” single that would sit on the impact racks of the London record stores they visited, alongside other Orlando-produced Hi-NRG records, Arthur Baker-produced NYC electro jams, the first wave of Latin freestyle cuts (then dubbed ‘Latin hip hop’), and chugging synth-disco cuts from the European continent (particularly Italo-disco).

During the formative portion of their career, between 1984 and the end of 1987, Pet Shop Boys largely looked to New York – then the global epicentre of the emerging dance music culture – for inspiration, albeit with occasional glances towards Italy. They took their 12” versions seriously, complementing their “memorable songs with the latest dance beat” with extended mixes by Baker, Shep Pettibone, Francois Kevorkian and freestyle pioneers the Latin Rascals. Appropriately, some of these were showcased on 1986’s Disco, a mid-priced remix album that helped introduce a whole generation to the artful potential of cutting-edge, high-tech electronic dance music.

The other key influence on their dance music interests at the time was Heaven, then London’s leading LGBTQ nightclub. From 1979 to the end of the 1980s, Heaven’s key resident DJ was Ian Levine, a former leading light of the Northern Soul scene who became a significant figure in the emergence of Hi-NRG as a wider cultural force.

The style was masculine, camp and exuberant, pairing throbbing, arpeggio-driven electronic grooves with songs that could be in turn sleazy, celebratory and highly sexualised. It was dance music by, and for, the gay community – a natural successor to disco built with drum machines, synths and early samplers, rather than soul musicians and orchestras.

Hi-NRG would, in the latter half of the 1980s, provide the framework for countless electronic pop songs. Its commercial zenith was not down to Levine, but a combination of Tennant and Lowe’s second and third UK number ones – ‘It’s A Sin’ (fittingly remixed by Levine on a separate 12” single) and ‘Always On My Mind’ – and the PWL hit factory of producers Stock, Aitken and Waterman. Their productions dominated the UK singles chart, peaking in the late 80s via their work with singing soap stars Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan.

Hi-NRG eventually ran out of steam in the early 90s but was effectively replaced by Eurodance. Naturally, this was another importance influence on the Pet Shop Boys in the 1990s and can be seen in the buzzing stomp of the remixed single version of ‘Yesterday, When I Was Mad’, its’ B-side ‘Euroboy’, and various revisions by the Trouser Enthusiasts. Tennant and Lowe also showcased Eurodance on their Discovery tour of Latin America in 1994, performing covers of Blur’s ‘Girls & Boys’ (based on their own remix of the original track), Culture Beat’s ‘Mr Vain’ and Corona’s ‘Rhythm of the Night’.

By the time ‘Always on My Mind’ hit stores in December 1987, Tennant and Lowe’s dancefloor gaze had started to shift. Leading the remix 12” was an extended rework the pair completed with PWL engineer Phil Harding. Halfway through, it moved away from the track’s Hi-NRG roots towards a style that was in the process of taking the UK by storm: Chicago house.

Much has been written about Britain’s acid house movement and the ‘second summer of love’, much of it heavily mythologised, but there’s no doubt it was a genuine moment of social and cultural change – one that turned the UK into the world’s first ‘house nation’ and set dance music on a course to global domination.

By the time national newspapers portrayed acid house partygoers as folk devils in the summer of 1988, Tennant and Lowe were putting the finishing touches to their dance-focused third studio album, Introspective. Still their best-selling album, it captured the moment more than any set they’ve made before or since.

Housed in a dazzlingly colourful sleeve and featuring extended, club-friendly tracks, Introspective marks the moment where the saucer-eyed acid house movement became part of the pop conversation. The album’s most enduring moments, ‘Left To My Own Devices’ and ‘It’s Alright’ (a fine cover of Sterling Void’s earlier Chicago classic), brilliantly updated producer Horn’s “memorable song with the latest dance beat” mantra for the acid house generation. Introspective was both an authentic dance album and a magnificent pop one: a blueprint that Tennant and Lowe later returned to, with an updated palette of dancefloor influences, on the Stuart Price produced Electric (2013) and Super (2016).

As we now know, house would become the dominant form of dance music in the decades that followed the second summer of love, mutating into multiple sub-genres and micro-styles at a rapid rate. These initially underground mutations, and the rising fame of the DJs who championed them, can be tracked through the Pet Shop Boys releases of the 1990s – not just the club-focused remixes, but also 1994’s Disco 2 – a non-stop mix crafted by Danny Rampling at a time when DJ-fronted releases were becoming increasingly popular – and the producers Tennant and Lowe opted to collaborate with in this period.

Alongside New York-linked producers Danny Tenaglia, David Morales, Tom ‘Superchumbo’ Stephan and Peter Rauhofer (who co-produced a cover of Raze vocal house classic ‘Break For Love’ with Tennant and Lowe in 1998), there were also studio dalliances with British creators of crossover club hits K-Klass and Faithless members Rollo and Sister Bliss (who brought the growing popularity of trance to several tracks on 1999’s Nightlife).

Then there was Tennant and Lowe’s work with Brothers In Rhythm. The trio’s glossy and uplifting early singles (most notably ‘Such A Good Feeling’) landed at a time when the previously united UK scene was splintering, with the freshly minted, club-focused ‘progressive house’ style developing in opposition to the wilder, rave-friendly breakbeat hardcore and jungle-techno movements.

Brothers in Rhythm initially re-framed 1990 B-side ‘We All Feel Better In The Dark’ as an ambient house cut (a nod to the fast-rising chill-out scene) before co-producing ‘Was It Worth It’ – one of Pet Shop Boys’ most unashamedly joyous, Italo-house influenced moments. Then came their 12” version of ‘Go West’, which morphed into a psychedelic progressive house workout as it progressed.

While progressive house eventually turned into a caricature of itself (something that befalls many styles of dance music), its initial expressions were undeniably forward-thinking, albeit frequently shorn of house music’s foundational Blackness. The influence of progressive house on Lowe, and particularly the bass-heavy, bleep-adjacent early output of William Orbit and Dick O’Dell’s Guerilla Records imprint, is evident in the sound of 1993’s Relentless – initially a partner, limited-edition accompaniment to the more pop-fired Very.

While still a very Pet Shop Boys release, Relentless was arguably the most ‘underground’ dance record the duo released in their first two decades. Typically, they outdid themselves in the early 2000s by diving headlong into the nascent electroclash scene via raw and club-ready remixes of Atomizer, Yoko Ono and Rammstein.

That Tennant and Lowe embraced electroclash is not surprising; it was the first sub-genre of the new millennium to mine the 80s electro, new wave and synth pop scenes for inspiration. It would not be the last; in many ways, dance and pop music’s 21st century story is one of regurgitating and lightly re-tooling their shared electronic past – and, for good measure, the sound that preceded it, disco.

Electroclash was expressive about its influences – Pet Shop Boys included – and in response Tennant and Lowe requested remixes from leading exponents including DJ Hell and Tiga. While electroclash’s popularity owed much to secondary scenes in New York and London, the sound’s roots lay in Munich – a reflection of the growing role Germany was playing the global dance music conversation.

Pet Shop Boys had looked to the country before, incorporating elements of trance in their music and requesting remixes from Jam & Spoon and WestBam, but now – like many dedicated clubbers across the world – their sights were firmly set on Berlin, Frankfurt and Cologne. The latter city’s brand of minimalist techno, promoted by Kompakt Records, was generally deeper and warmer, with more expressive nods to poignant and melancholic synth-pop sounds of the past.

Elements of the latter sound are audible, albeit wrapped in Trevor Horn’s grandiose production, on 2006’s Fundamental. The album also contains the duo’s picturesque tribute to the joys of minimalism as an aesthetic, ‘Minimal’ – an exquisitely timed and likely deliberate nod to minimal techno’s then unstoppable momentum. The remixes commissioned to accompany the album – including rubs from Kompakt’s Michael Mayer, then wonky techno specialist Trentemøller, and Roman Flugel’s Alter Ego project – back this up. There was also, in tribute to electronic pop’s European roots, a pair of remixes by late-1970s Belgian proto-techno outfit Telex, whose resurgence owed much to techno DJs on both sides of the Atlantic championing their earliest records.

It was a sign that dance music and pop were becoming addicted to mining their own pasts. The ghosts of synth pop and dance pop of old – alongside hip hop and R&B – haunted the output of pop’s leading production collective of the period, Xenomania, to whom Tennant and Lowe turned to for their next album. Xenomania were just the latest in a long line of synth-loving dance pop producers-as-hitmakers; during the 90s, Beatmasters had performed that function, delivering work for the Shamen, Moby, Erasure and, as you’d expect, the Pet Shop Boys.

Stuart Price, via his work with Madonna, New Order, The Killers, Jessie Ware and George Ezra, is the 21st century equivalent. He began his career as an underground outlier of what was to come, referencing 80s electro, Hi-NRG and Italo-disco (sounds he’d first fallen in love with via Pet Shop Boys records) during the big beat era of the late 1990s. His later ascendency to in-demand producer not only speaks for the quality of his work, but also pop’s reliance on tapping into earlier expressions of electronic dance music.

Price’s involvement with Pet Shop Boys began at a time when Daft Punk were in their 80s-influenced dance-pop prime and dance music was taking the United States by storm. That country’s embrace of EDM was propelled by driving rhythms, buzzing trance riffs, catchy melodies and the kind of whizz-bang electronics that Pet Shop Boys had always done so well.

Price didn’t exactly turn Tennant and Lowe into ‘EDM’ stars, but you’ll find no better rushing, trance-infused, stadium-ready dance-pop record than 2012’s ‘Vocal’, itself a wholehearted celebration of the joys of going out dancing (“you got it on one song,” Lowe dryly commented to Tennant during the BBC’s recent Imagine documentary on the pair). In some ways EDM is dance music dialled up to the max with lashings of pop thrown in, designed to deliver memorable live experiences via performances that utilise vibrant visuals and light shows.

Pet Shop Boys live performances of the last 15 years – bar the deliberately pared-down Dreamworld – have frequently tapped into this aesthetic and approach. For proof, check out the concert films of Pandemonium and Inner Sanctum. Musically, they’re energetic and exuberant, utilising sometimes radically updated or retro-futurist manifestations of Pet Shop Boys hits, largely programmed and sequenced by Price. Inner Sanctum took place at the Royal Opera House, turning the grand old London venue into a scaled-down EDM rave. To do that, almost four decades into their career, is very Pet Shop Boys (as was incorporating the rhythms of reggaeton, then a fast-rising musical movement, into 2016 single ‘Twenty-Something’).

So we come to Nonetheless, their triumphant new album. Like Tennant and Lowe’s best work, it’s timeless, delivering perfect pop songs with disco strings underpinned by vibrant synthesizer melodies and sequenced basslines. It also contains countless sonic references to the music Pet Shop Boys made – and danced to – during their imperial phase and the dance music explosion that followed.

It’s nostalgic, but then so is much of pop music in the third decade of the 21st century. Where they led, others have followed. Don’t bet against them mining current and future dance music developments for inspiration; after all, they’ve always been masters of “memorable songs with the latest dance beat”.