Outside of friends and family, Perry Como’s is the voice I know best. I can hear him now, rising up, through the floor of my bedroom. It is a Friday night in 1981, and that voice is initiating me into an unknown, adult world of destined romance and marital crisis, of jail time and masquerades. Everything in Como’s songs is fated, delivered with such weight and grace.

They call it easy listening, and it’s true, but to me it’s easy as in ineluctable, as in elemental, a form of unhesitating presence that fully exists in the moment. This is Como on ‘It’s Impossible’, one of his masterpiece performances. The lyrics are huge – "’Can the ocean keep from rushing to the shore? It’s just impossible"’ – yet he delivers them with an easy gravitas, as if he is on the other side already, as if he has accepted fate. Moreover, it’s as if he has literally become the change he sees in the world. He is the moon, waxing and waning, both the ocean and the shore. He has the echo in his voice of an old laughing hermit sat on a stool in an auditorium: Mr Natural.

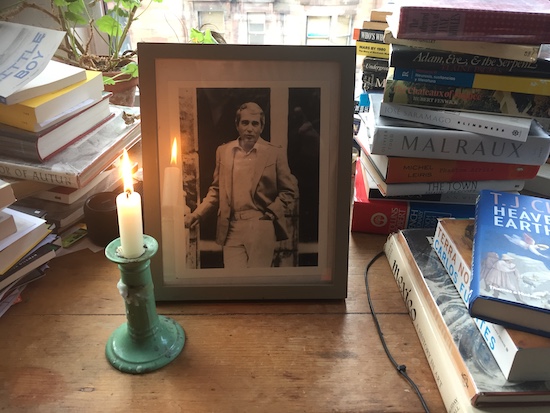

And what a look. I love Como’s look. I love how in photographs he purses his lips as if he’s whistling, as if they have just nabbed a candid shot of him making love to life, which was after all his philosophy, as he sang: "’make love to life, let life make love to you."’ I can’t think of any better advice. Who says Como wasn’t political?

But, yeah, I’m upstairs, in the loft, which I had turned into my bedroom, back at home in 1981, with cool sloping walls and with a skylight over my bed where I would fall asleep looking up at the stars. My dad and I had a secret ritual where once my little brother and sister had fallen asleep on a Friday night I was to come to the top of the stairs and wait for his signal. He would wave me down and we would sit up late eating toasted scones with butter and jam, drinking tea as he played Como on his stereo – ‘Tie A Yellow Ribbon’, ‘And I Love You So’, ‘For The Good Times’. ‘When You Were Sweet Sixteen’. My dad called it Como-therapy, that’s what he would say to me, "’it’s time for some Como-therapy"’, and you know, it really was.

My father did much to initiate me into his vision of masculinity. He taught me how to throw a punch, gave me gold rings, got me fitted for suits, encouraged a work ethic which I have never been able to shake. He kissed me and called me his golden boy.

And when he would play me Como during our Como-therapy sessions, I felt like he was initiating me into all the possibilities of the future. Heartbreak, loss, intense and body-wracking love, memories, fortitude, endings and beginnings; all delivered in this beatific, easy style. Como sang from inside the words as the embodiment of the sentiment that speaks them, which to me is the sign of a true singer.

Como is not an interpreter of songs, like Sinatra, which is part of the reason why Sinatra is taken much more seriously as an artist. Como does not get in the way. These are not ‘versions’. Perry Como recordings are ur-documents, the lineaments from which all other versions will be re or de-constructed.

And hearing these songs in the lap of my father, I felt for the first time the calling of my own life, my own manhood, and of my responsibility towards it. I felt awe at what it is that we are called to say yes to. There’s Como, in there the whole time, his lips pursed, like he’s whistling.

I associate Como LPs with a certain kind of décor, maybe a similar décor to what I think of when I think of ‘Wichita Lineman’, another suburban existentialist masterpiece. I’m thinking of teak cupboards beneath stereo systems where all the Como LPs were stored alongside a program from the legendary gig he played at the Kelvin Hall in 1975. I’m thinking of school photos, and of units from Habitat, a drinks cabinet on wheels. I realise what I’m thinking about, actually, is the suburban topography of that twentieth century moment where working class people were earning more than their parents, buying their first homes, and gaining full access to culture for the first time. That’s what I think of every time I see that beautiful Como LP box set The First Thirty Years like a time machine . What a title. No need for elaboration – this is the body of music, the first thirty years.

I only remembered Iggy Pop was a Como fan when he played a track on his radio show recently. Iggy was the animating spirit of my first novel This Is Memorial Device in a way that Como is in For The Good Times. To think that Iggy heard that in him. My dad and his brothers always praised Como for his clean-living ways and his high moral standards, even as they behaved like maniacs themselves. Still, I have long imagined Como singing ‘Dirt’ by The Stooges – "’I’ve been dirt/but I don’t care/because I’m burning inside/I’m just a-yearning inside/and I’m the fire of life"’ – and it becoming the palimpsest over which every version of that song would be written, because I know that Como – and this is almost unique to Como, and to Iggy, too – would give equal weight to both the fire, and the dirt, as elementally easy combinations. This to me is the lesson of Como and why I write, every day, with a framed photo of him whistling on my desk. And with a candle lit in front of it, too.

David Keenan’s For The Good TImes is out now via Faber, buy it here