With his panting breath and dripping sweat infused in each page of his memoir, Patrick Cowley describes himself on his knees, bending over and "worshipping Phallus." He touches the ground beneath a much-used glory hole and with complete sincerity calls for it to be consecrated territory. Having just indulged in the pleasures of a "golden idol," Cowley offers sacraments to show his appreciation, and if religious offerings were not enough, he sends thanks directly to the Father. This might just be a bit of tongue-in-cheek humour, but by adopting religious language in descriptions of conventionally irreligious exploits, Cowley shatters our expectations of gay freedoms in the 1970s. We’re left celebrating gay liberation as a period that empowered homosexual men to self-govern without restraint.

Spanning the liberation period from Stonewall in 1969 to the dawn of AIDS in 1981, record label Dark Entries’ publication of Cowley’s private journal, Mechanical Fantasy Box, captures without concession one man’s proud and unabated expression of sexual freedom. The diary’s writer and intended sole confidant, Cowley, is known as the pioneer of Hi-NRG, disco’s electrified successor, for his extended remix of Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love,’ and for his collaborations with Sylvester, the gender-bending, falsetto-singing disco mainstay. By recording the spectacular details of his indulgence, Cowley gives us a sense of the vibrancy of the gay liberation period.

Cowley’s pursuits seem effortless, self-manifested, however what his actions conceal is the might of self-organisation that had taken place in the relatively isolated Castro District of San Francisco to give rise to his sexual freedom. With leaders like Harvey Milk, the famed gay District supervisor, the Castro community established some ninety gay bars in the city and a further hundred and fifty gay organisations, a catch-all for church groups, social service groups, and business associations. Nine gay newspapers were set up, two gay charitable foundations, and three gay Democratic clubs, one of which grew to be the largest Democratic club in California. Cowley’s insatiable lust is the torch that allows us to navigate this web of gay infrastructure and celebrate the period for inculcating authentic and uninhibited sexuality.

The immense freedom characteristic of the gay liberation period is exhibited in the work’s release format. Cowley’s sexual adventures were read on stage in late November 2019 by a literary group in London called Naked Boys Reading. Aptly named, this troop of boys read the hearty details of Cowley’s journal on stage to a large audience, completely, unequivocally naked. Through this display of the readers’ most unvarnished state, the release of Mechanical Fantasy Box reveals the honesty lying at the foundation of the gay liberation period.

Dark Entries’ reissue of Roy Garrett’s Hot Rod To Hell similarly honours the achievements of the gay liberation period. A recording of 48 salacious poems supported by an electronic composition by Man Parrish, Hot Rod To Hell is Roy Garrett’s first and only foray into the arts beyond the screen. A prolific gay porn-star and one-time poet, Garrett was the star of numerous 1970s pornographic films including Men Come First and Handsome, and has been memorialised by an ex-lover on Facebook as having "one of the most perfect complexions ever seen on a human being." Unlike Cowley, who found his sexuality unopposed in San Francisco, it was only Garrett’s boundless self-confidence that allowed him to overcome the limitations conferred by mainstream New York society.

Sexual exploits of a kind found in Mechanical Fantasy Box are marred in Garrett’s accounts by references to being used in a cold and brutal fashion. His companions want to "cut me up / Because I’m such a fag," a far cry from Cowley’s affectionate and well-intentioned partners. He is "kicked and beaten until my life ends," however endowed with a level of self-assurance archetypal of the period, Garrett is able to playfully reject the seriousness of the attack, saying that "it’s a shame you have done this / We could have been friends." Garrett overcomes the seemingly unforgiving nature of his environment because of the supreme self-confidence accessible during the queer 70s.

The gay liberation period is praised for conferring homosexuals with the conviction to confront their opponents. Garrett looks into the eyes of one of his lovers, brushes up against his leather, and comments that "I knew that at lengths / I had arrived / And that / I was a man." He "cruises" between two of the great gay institutions of the time, The Saint and Mineshaft, and when he finally reaches the glory hole, jokes, "and it sucked!" He’s able to make light of the transactional nature of his exploits, knowing that "tonight / I’ll use you / And you’ll use me," as he’s simply thrilled to have met someone to spend the night with. It is only with the heights of free sexual expression in the 1970s that Garrett could have considered it appropriate to cast his homosexuality as inherently American, commenting that after a night spent with another man, he’s "One slightly used / All American male." Alongside the directness of the spoken-word format, Man Parrish’s cosmic sound-tracking emphasises the period’s lack of vulnerability by interlacing the entire listening experience with a sense of drama and theatrics.

Through Garrett, Dark Entries recaptures the positivity of the 1970s that was lost to tragedy of AIDS. When it became clear that AIDS was particularly affecting gay communities, the strength of New York City and San Francisco as beacons of possibility shrunk and each advancement in gay liberties was recast by homophobes as evidence of the community’s misdeeds. With the narrative around gay liberation rapidly shifting from defending sexual liberties towards more pragmatic efforts at disease containment and treatment, Dark Entries has turned to the artists of the late 1970s to preserve the period’s initial spirit.

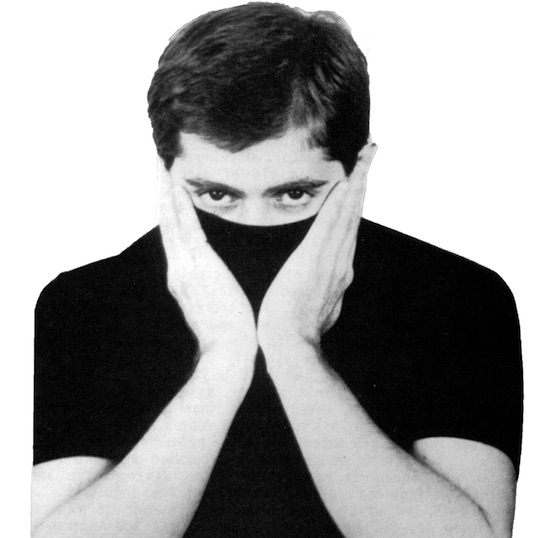

Maxx Mann

Continuing this commemorative effort, Dark Entries’ most recent release of Maxx Mann’s self-titled album steers past the hyper-sexualised liberation world common to Cowley and Garrett and into the AIDS crisis. Maxx Mann’s sole album is a synth-laden celebration of gay sexuality. A little-known electronic duo, Maxx Mann is distinguished by the act’s lyricist and vocalist, Frank Oldham Jr, who until recently was one of the more prolific voices in AIDS advocacy and occupied the CEO role at America’s National Association of People with AIDS (NAPWA), a 30 year-old institution committed to eliminating HIV.

Much like Cowley and Garrett, Maxx Mann identifies the euphoric heights reached during the gay liberation period. Nearly identical to the imagery found in Mechanical Fantasy Box, Oldham Jr’s proud exploration of his own sexuality comes through in his adoption of religious language. In the album’s opening track, ‘Leather Man,’ Oldham Jr. expresses how the pursuit of sexual gratification is more redeeming than his Christian faith, crying out with pleasure that "heaven’s not as hot as hell!… heaven’s bound to understand!" Immediately, Oldham Jr. is differentiated from his historical peers and cast as the empowered product of gay liberation. Maxx Mann provides an impression of uninhibited sexuality similar to Cowley’s experience but like Garrett, the album simultaneously notes the dangers associated with open displays of homosexuality.

Just as violence is threaded into Garrett’s sexual activity, Maxx Mann conflates sex with something fierce and vicious, something attractive but to a degree, to be endured. Oldham Jr. comments that "Like a killer returns / To the scene of his crime I came back to you," despite this experience leaving him "bloody and bloody and bloody and blue." Sex itself is represented as a product of contextual animosities towards homosexuality. Forcefulness is fetishised, with sexual partners lauded for their dominance, with the act of "Shove[ing] it right in front / Of my face each night" construed as the ultimate act of desire. Dark Entries’ release of Maxx Mann celebrates the gay liberation period but does not shy away from revealing the limits of its progress.

Understanding that Maxx Mann is the band’s sole output is in itself evidence of the era’s quick descent from hedonism into crisis. Shortly after the release of Maxx Mann, the album’s musical lead Paul Hamman fell victim to AIDS. Rather than pursue the path outlined by his past as a musician between Berlin and New York, the impact of AIDS led Oldham Jr. to renounce music to work in public policy and advocate on behalf of his disenfranchised community. No more were the glitzy electronics and confident tones on Maxx Mann definitive of the homosexual experience, but rather the stoicism and solidarity of the gay community. Where Oldham Jr.’s moniker throughout this period was the album title itself, Maxx Mann, a character described as warm, sensual and resilient, the disappearance of this name following the release suggests the passing of the 1970’s positive disposition, something Dark Entries is seeking to reawaken.

Underpinning these three reissues is the acknowledgement that had HIV been handled more effectively in America, then the creativity and enthusiasm of the 1970s might well have extended into successive decades. Dark Entries is protesting the political and welfare institutions that failed to intervene in the spreading of a virus, inaction that speaks to entrenched discrimination against sexual minorities and divisive us-vs-them politics. By reissuing the work of Cowley, Garett and Maxx Mann alongside the most progressive of modern sounds, Dark Entries is sequencing these artists within a musical narrative that celebrates their contribution to contemporary culture and enables them to access lives beyond what their government was complicit in stifling.

Patrick Cowley’s Dark Entries is out now, Maxx Mann is released later in March. For more information, visit the Dark Entries website