In 1987 Oliver Reed went on the chat show circuit to promote his latest movie, Castaway. What followed were three of the actor’s most infamous television appearances, the kind that regularly crop up on clip shows or can be accessed via YouTube. There he was on The Des O’Connor Show threatening to expose himself. There he was on Aspel And Company doing an aggressive musical turn to the enthusiastic – but slightly petrified – applause of Su Pollard. Over in the States the story was much the same, prompting David Letterman to cut to a commercial just as things were threatening to overspill into violence. These weren’t the first incidents of outrageous drunken behaviour, nor would they be the last. Four years later Channel 4 halted transmission altogether during an episode of late night live discussion programme After Dark. Reed was being especially obnoxious and constantly referring to his fellow guest Kate Millett as "big tits". Such feminist credentials had gotten him into similar trouble almost two decades earlier when appearing on The Johnny Carson Show alongside Shelley Winters. She emptied her glass of whisky in his face.

Reed and drink became inseparable in the public perception, helped along during the last decade of his life by his idolisation among the lad mags and their offspring (inevitably there was an inebriated appearance on The Word). Following his death in 1999 during the making of Ridley Scott’s Gladiator, the Maltese boozer in which that fatal heart attack had taken effect added a subtitle to their name: ‘Ollie’s Last Pub’. Whether this was an act of acclaim or exploitation depends on where you sit. Some fans treat the place as a shrine, and yet it also sells commemorative plates, T-shirts and mugs. Isn’t the point getting missed somewhat? Going home with Reed emblazoned across your chest celebrates the alcoholic but forgets the actor. Whatever happened to him in all this?

Long before After Dark, O’Connor and the rest – before chat shows even had a circuit – Reed was fresh out of National Service and struggling to find his way in the film industry. Depending on who you read he’d possibly worked as a bouncer and maybe even as a stuntman. That burly frame obviously had its uses and it hadn’t escaped the notice of producers either. His earliest onscreen appearances were a succession of toughs, bullies and bastards. He beat up Norman Wisdom in The Bulldog Breed (1960) and stamped on the chocolates intended for his date. In Beat Girl (1959) – a salacious, censor-bothering exposé of that newly discovered breed, the teenager – he jived away with dead-eyed menace to terrifying effect. Even in period costume he could summon up the aggression. The Two Faces Of Dr Jekyll (1960) provided just a couple of lines of dialogue, but that was more than enough to make an impact. A few threats in the direction of Christopher Lee and Paul Massie and the scene had been completely stolen. The appearance culminates in him receiving a good kicking, but the real damage had already been done.

The latter was one of a number of Hammer productions to make use of Reed during the early ’60s. His place on the cast list was haphazard, meaning a lead role was as likely as a single-scene supporting turn, yet the character type was set in stone. Whether it was a horror, a pirate movie or a Robin Hood flick, Reed was always on the side of the villains. And this was a good thing. Unhindered by concerns for audience sympathy he could concentrate his attentions elsewhere. In The Scarlet Blade (1963), for example, it is left to Jack Hedley to provide the bland heroism; Reed gets far the meatier role as a double-crossing Roundhead. He may not make it to the final act, but there’s nothing to stop him being charming, dastardly or charismatic in the meantime.

The highpoint of the Hammer years was The Damned, a bleak little science fiction picture directed by Joseph Losey and released in 1963. It was partly filmed in Weymouth, whose safe seaside haven is terrorised by Reed’s biker gang. They’re even granted their own theme tune – "Black leather, black leather, rock rock rock! Black leather, black leather, kill kill kill!" – which they casually whistle as they lay into the tourists. He keeps a blade in his brolly and very possibly enjoys incestuous feelings towards his younger sister, played by Shirley Anne Field. The dynamics and jealousies of their relationship are soon clouded out by plot concerns – a group of radioactive children hidden away in a military facility on the Devonshire coast – but not before Reed has presented us a fascinating specimen. He’s a tormented man, and a dangerous one. You understand why a gang of youths would follow him: there’s a threat to his presence, but also a thrill.

Two years later and Reed was heading up a gang once more in The Party’s Over, a particularly sour look at a bunch of ageing hipsters: "Chelsea aboriginals," as one outsider puts it. Reed’s first scene shows him pouring booze over some fella hanging perilously from a first floor balcony. It’s a typically nihilistic act in a film unafraid to reveal its characters’ darker sides. That man behind the dead-eyed jive in Beat Girl has returned, but now we get to spend more time in his company. We witness the girl-chasing, the drunkenness and the distastefulness. We also witness the charm that goes with such boorishness, not to mention the intelligence. As with the Hammer films, Reed is playing second fiddle – American import Clifford David is the clean-cut male lead – which only allows the greater opportunity to turn in a proper, fully-rounded portrayal. The script demands "a real bastard", to quote it directly, not some loveable rogue headed towards redemption. That’s an absolute gift to the upcoming actor prone to surveying the seedier side of life.

It was around this time that two of British cinema’s most notorious directors had come calling. Michael Winner and Ken Russell now have a reputation for excess and bad taste, yet things weren’t always so. Their works with Reed are all models of restraint in the wider scheme of things, and far more intelligent than either is generally given credit for. Two of the Winner films – 1964’s The System and 1967’s The Jokers – are smart little comedies, very stylish and snappily paced. They also allowed the actor a rare chance to demonstrate his lighter side. The Russell collaborations provided him with further means of moving beyond the bastards. Made for the BBC, these were pictures about artists or composers, told in often impressionistic fashion. Reed played the likes of Claude Debussy and Dante Rossetti, complex characters who demanded a little more than that brutish charm which had previously served him so well. The Debussy Film (1965), in particular, is a standout. With very little dialogue at Reed’s disposal, he is instead required to react. That charisma he’d been honing these past few years became all the more important, except that this time it’s removed from the usual hint of violence.

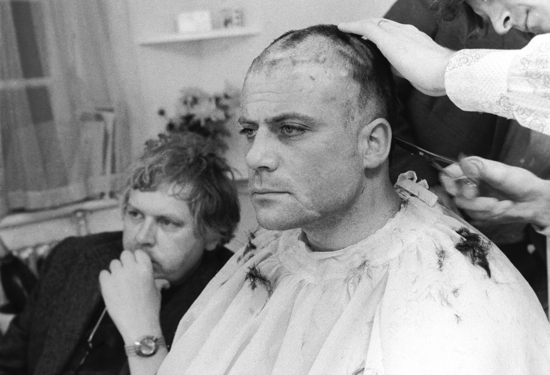

Reed was becoming increasingly well-known as the 1970s approached. His fame had reached a point where he finally felt able to work with his uncle, the director Carol Reed, without facing accusations of nepotism. He played Bill Sikes for him in the musical Oliver!, a telling piece of casting given how Robert Newton, another of the acting world’s most chronic of alcoholics, had previously done the same in David Lean’s 1948 adaptation. Oliver! was a massive hit, winning six Oscars and raising Reed’s profile further. His relationship with Russell had also moved away from television and onto the big screen, firstly with Women In Love (1969) – much more than its famous nude wrestling scene – and then with The Devils (1971).

"Now there’s a man well worth going to hell for, eh?" Reed plays Father Grandier, the 17th century priest who presides over the self-governing city of Loudon. Despite, or rather because of his religious standing, he is lusted after. The womenfolk of the city attend confession solely to be in his company, while the fantasies of Vanessa Redgrave’s hunchbacked nun picture him as Christ, down from the cross so as to satisfy her. The other nuns in her order perform mock marriage ceremonies to him. Grandier, as played by Reed, is almost an extension of the gang leader from The Party’s Over. He’s proud and more than a little arrogant. He takes advantage of the female attention. And he justifies such hypocrisies thanks to his considerable intellect. Yet he’s not oblivious to a downfall either, and soon becomes the victim to both Redgrave’s frustrated ravings and the political machinations of the time. In Russell’s hands The Devils becomes consumed by hysteria, yet Reed is its anchor. He plays every moment completely straight, acts as the film’s sole area of sanity and in doing so highlights the absurdities of its tale. Russell claimed this to be his only political work, and it’s thanks to the command of his leading actor that it proves so overwhelmingly effective.

The Devils was the absolute peak in terms of Reed performances and one that also heralded the end of his career as an actor in solely British films. The next three decades saw work in the US, Italy, Canada, even Libya and Iraq. There was the odd UK production too, but these efforts were rarely to the standard we’d seen previous. He made trashy historical epics, trashier fantasy adventures and even appeared alongside Olivia Newton-John. There were occasional glimmers of outstanding work – Richard Lester’s Royal Flash (1975), David Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979) – but such instances were rarities. The key performances during his later days were those on the chat shows. They attracted the press; the films which they had been intended to promote were secondary or forgotten altogether.

Yet there’s a lineage between the chat show persona and that run of pictures leading up to The Devils. Just as the ’60s work would gradually reveal Reed as one of the finest British actors of his or any other generation, so too would it slowly cultivate the man who sat opposite Michael Aspel, David Letterman and the rest. The intelligent drunk, the well-spoken bully, the equal measure of charm and threat – all find their root in these early movies. The real-life Reed fed off those various onscreen Reeds and soon overtook them, which is a genuine shame. The next time you see one of the chat show appearances resurrected on a clip show or read yet another celebratory article running down his drunken ‘achievements’, just remember that he did it all so much better when there was a script in hand and a production crew behind him. The Damned, The Devils, The Debussy Film, The Party’s Over, and so on: this should be Reed’s real legacy, not slurring insults at a feminist author or offering to get his cock out before the watershed.

The original UK theatrical version of The Devils is released by the BFI; complete details here.