In the second season of The Sopranos, Christopher Moltisanti wakes from a coma following a near-death experience. The gangster has envisioned the afterlife. “The Emerald Piper,” he warns darkly. “That’s our Hell. It’s an Irish bar where it’s St Patrick’s Day every day forever.”

Being in Oasis seemed a little like this. The Gallaghers brothers would roll into some European or American city to perform, management would book out the nearest Irish bar for after the show, and the dark walls and mock Celtic furnishings provided an unchanging backdrop to the Gallagher court.

In a new book, Ted Kessler and Hamish MacBain recount one such incident. It is 2009. Liam Gallagher has given up smoking to preserve his voice on tour. This means that he is simply stealing everyone else’s cigarettes and smoking anyway. He is falling out with his older brother, who is picking the label from a bottle of lager like a scab, over Noel’s use of the term “guys” instead of “geezers.” Like Tudor courtiers, security staff and music journalists trade micro-gossip about miniature progressions observable in the brothers’ relationship, on which all of their positions are contingent. As with the fictional New Jersey crime organisation, Oasis were a conspiratorial and macho family firm in which illicit thrills struggled to mask a long and slow decline that nobody knew how to reverse.

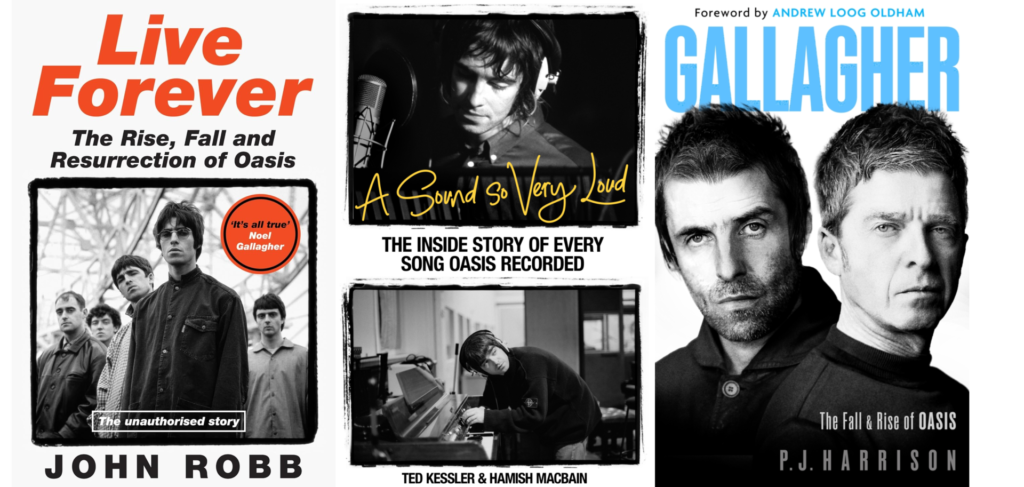

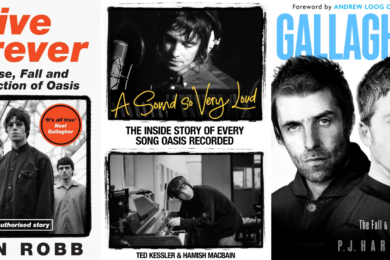

If anyone knows anything about long and slow declines then it’s music journalists. In 2025, almost all of the print sector that was recognisable even at the end of Oasis’ career has been gutted and erased. Can anyone blame demobbed hacks for taking a rarely available fast buck and producing a quick turnaround Oasis tome? This summer sees the release of Live Forever: The Rise, Fall And Resurrection Of Oasis by John Robb, Gallagher: The Fall And Rise Of Oasis by PJ Harrison, and A Sound So Very Loud: The Inside Story Of Every Oasis Song Recorded by former Q editor Ted Kessler and former NME staffer Hamish MacBain.

The latter book takes its format from Ian MacDonald’s 1994 Revolution In The Head, a book whose weird energy came from mourning that The Beatles mattered because they arguably accelerated the undermining of the intellectual foundations of Western culture, a decline thesis disguised as a rock book. But where the beats of that story made a track-by-track format delicious, Oasis is a story of unrecoverable decay.

Unless you caught them in 1994 or 1995, they were almost always getting worse. Today, the band’s successful legacy management project seems to agree: their 2016 Oasis: Supersonic documentary crafts an intoxicating and boosterish narrative by stopping the clock at their 1996 Knebworth shows. The first three albums receive lavish, bonus-packed reissues: the rest do not.

After Be Here Now (1997), Standing On The Shoulder Of Giants (2000), Heathen Chemistry (2002), Don’t Believe The Truth (2005) and Dig Out Your Soul (2008) sold millions but were creative failures. Of the band’s top 40 streaming tracks, only eight come from their 21st century albums. Deeply flawed for often completely contradictory reasons, Oasis made bad LPs that were too cocaine blasted or too hungover; back-to-basics projects or nakedly 1960s homage pieces. They were not even admirably consistent in their commitment to a single knucklehead idea, like Status Quo, nor prone to fascinating and eccentric failures, like their nemesis Robbie Williams’ head-scratcher Rudebox.

But the best writing on Oasis – scattered between David Cavanagh’s meticulous, myth-busting door stopper The Creation Records Story: My Magpie Eyes Are Hungry For The Prize (2000), Alex Niven’s essential 33 ⅓ reappraisal of Definitely Maybe, and Paulo Hewitt’s first blood, Getting High (1997) – has not so far contended with the aeons after their peak, the thing that Oasis were for more years than they were not. How does this new crop of books deal with this problem?

The accepted narrative, write Kessler and MacBain in their book’s introduction, is that Oasis “musically, never matched the heights of the mid-90s.” They argue that to listen again to those albums without the weight of expectation is to find “much to enjoy, and songs that are an important part of the story of this most important of bands.” But what is that story?

Oasis began the 2000s at a crossroads. At the end of 1999, Creation Records had been dissolved by Alan McGee, who sold the remainder of the label to Sony. Though McGee revelled in his image as the man who signed Oasis, he had spent the band’s rise first as an absence – in convalescence from a serious drug-induced breakdown across 1994 as they broke – and then later as a nuisance, frozen out of the Be Here Now campaign after disastrously hyping an album that “would sell twenty-million copies”, to journalists. Oasis set up their own Big Brother imprint, licensed under Sony. This defined their second phase in ways good and bad, allowing them a dedicated and autonomous staff, but no master at the top to fear or impress.

At the same time, Noel Gallagher had dilemmas. Having sworn off cocaine and sold Supernova Heights, his gaudy Britpop Xanadu in Belsize Park, his songwriting had shifted unhelpfully to damaged finger pointers about the emptiness of celebrity life. ‘The Fame’ and ‘Let’s All Make Believe’ became opportunities to write about his new class in the same bitter and melancholic way that he had written about his old one, in songs like ‘Half The World Away’ or ‘Rocking Chair’. But bloodshedding about the toughness of the top was unlikely to maintain Oasis’ family car and dentist waiting room ubiquity. This could be any story of working-class attainment gone sour. The specific example he seemed to relate to was that of George Best, cribbing the footballer’s “where did it all go wrong” punchline for a song title and using the term “George Bested” to describe experiences of high stakes failure, like their lethargic and weirdly sad 2004 Glastonbury headline set.

But if high stakes failure sounds exciting, the result was the opposite. A Sound So Very Loud is polite to Oasis’ 2000s material, avoiding critical judgement in either direction in favour of anecdotes and digressions that illustrate how the material fits into an evolving version of the group. It’s meticulously researched, and often perceptive with it, but as the book progresses any sense of narrative simply becomes relegated to one thing happening after another.

Instead, tragedy is glimpsed between the lines. In 2004, the book details, Oasis booked out the same Welsh studio where they had recorded Definitely Maybe ten years to the day later, in an attempt to recapture their earlier mojo. The first thing that everyone noticed was that the rooms were freezing. After two weeks the band conceded that they simply had no songs and went home. (“That was Noel’s fault,” summarised his younger brother. “He wanted to get all nostalgic.”)

Consequently, Oasis in the 2000s settled into a loose-fit arena psychedelia with all the mind-enhancing possibilities of a HMRC self-assessment form. Here was a band that had once brashly summarised the headlines of three decades of British pop music now reduced to ripping off Stereophonics. Listened to in the 2020s, albums like Heathen Chemistry or Don’t Believe The Truth carry the unappealing sound of strategic compromise, triangulated between Noel Gallagher’s desire to make lightly exploratory singer-songwriter rock, the perceived demands of a stadium audience, and everyone’s desire to keep the high-grossing show on the road.

By then, original members Bonehead and Guigsy had left, replaced by Gem Archer and Andy Bell. But what was so thrilling about early phase Oasis was the sound of relatively low skilled (and even lower glamour) musicians rehearsed relentlessly into a formidable and intense group. Was something lost when the band became staffed by assured jobbing musicians? What if Oasis had carried on as a stadium Fall, recruiting novice Longsight teenagers for that weekend’s Wembley booking? (Mark E. Smith, in memoir Renegade, wrote that he had met Noel Gallagher “a couple of times” and reported that the experiences made him “want to say, ‘Shut up!’”) Not that this mattered to that era’s weekly music press, who traded return-to-form reviews for bankable Gallagher access and front page covers.

John Robb’s Live Forever is of this tradition. Its USP is being the only book on the market with a new and extended Noel Gallagher interview, following the viral video Robb conducted with the elder brother last summer which hinted to fans that white smoke might be about to be seen above the mansions of Hampstead and Hampshire. Unfortunately, the interview is conducted at the exact point that the elder brother is compelled to omertà about the Oasis years. “Working with a family member is not always easy,” says Noel Gallagher with the kind of diplomatic understatement that only an estimated £400 million in gross revenue can buy. “You can push each other’s box pretty quickly but that was rare and we were all growing up and growing older.” (For context, in 2017 he was damning his sibling as a “filthy little narcissist.”)

Robb patiently makes the case for each Oasis album after Knebworth. His spirited, sometimes outright persuasive take on Be Here Now repositions it as a maximalist reflection of its heightened times. But overall, the book’s rush through the band’s second decade in its final fifty pages, seems to contradict his praise for them in that period. Robb is vivid and detailed on the druggy, after-hours Manchester bohemia of the early 1990s – Noel Gallagher was a regular at Hulme’s Kitchen, a squat turned nightclub in the decaying Charles Barry Crescent – but blurrier once the brothers board the train to Euston.

Robb contrasts Oasis’ Y2K years against a bland, “endless parade of talent show chancers” and the dominance of the iPhone (which was, in any case, only launched the year before they split.) But I’m less sure about this distinction. ‘Stop Crying Your Heart Out’, the only really enduring Oasis song from this period, was beloved of Simon Cowell, who recognised its game as roaring, extra mature schmaltz. Cowell made it a Saturday night showstopper for Leona Lewis and One Direction (later a lockdown Children In Need single.) Today, we understand the appeal of schmaltz – it was interrogated particularly well in Carl Wilson’s sympathetic appraisal of Céline Dion – but just how far removed were Oasis, who pioneered an increasingly shameless strain of blockbuster ballad, from this market? It’s telling that their nemesis shifts at this point from Essex indie band Blur to Robbie Williams (who, in any case, decidedly drubbed them in the sad lad banger stakes, and with his upcoming album Britpop is literally still fighting the war).

More than this, though, Live Forever contains frustrating errors that a Big Five publishing house should have caught and corrected. Oasis (“outsiders to the end”) were “passed over” for the 2006 Brit Awards and snubbed the ceremony. Except, they were nominated for two major awards, their most since Be Here Now. That the Gallaghers may have perceived this as a snub is at least revealing about the exhausting media attention that the band demanded as their relevance dimmed (in any case, they were awarded an Outstanding Contribution the following year.) Writing about 2008 thumper ‘Waiting For The Rapture’, Robb writes that the song is about Noel Gallagher “meeting his new partner Sara McDonald.” Is that the same “new partner Sarah MacDonald” who was introduced as inspiring 2002’s ‘She Is Love’ a few pages earlier? The Scottish PR Sara MacDonald, who was in a relationship with Gallagher for 23 years, would have an important influence on the Oasis story as it splintered, and it’s a biographer’s job to get these things right. It is not Robb’s fault that the inevitable future Oasis biopic will not exactly be Gilmore Girls, but it’s a shame that women such as tour manager Maggie Mouzakitis, Definitely Maybe engineer Anjali Dutt or longtime Creation staffer Emma Greengrass were not interviewed, and are only mentioned in passing if at all.

Someone unlikely to mix up his WAGs is PJ Harrison, former Sony Music executive turned Gallagher whisperer. His book is gossipy and brisk; and all the better for it. By way of credentials, Harrison was in the room when it happened. Unfortunately, in this case, it was the torrid sessions for Dig Out Your Soul, the last Oasis studio album, during which Liam Gallagher was seemingly anywhere but around his bandmates while Noel provided light relief by playing his favourite YouTube video of an Iraqi soldier repeatedly falling over. (“These experiences further galvanised my enthusiasm for the Gallagher brothers and deepened my understanding of them as people”, Harrison says at one point.)

How does his book critically engage with Oasis’ decline? In a single sentence, it turns out, listing their millennial album titles with the summary that they “failed to reach the same critical or cultural heights as earlier work.” By way of comparison, there are a full three pages given over to describing the interiors of Supernova Heights (“an Austin Powers fever dream” complete with mod-target mosaic bath). But the book’s unusual fusion of pop psychology, music business reporting and tabloid gossip does at least furnish us with clues. Brother Paul Gallagher described how success exacerbated the worst tendencies of both brothers from a childhood defined by paternal abuse, with Noel “becoming increasingly withdrawn and controlling” and Liam – who in Harrison’s view is plausibly neurodivergent – “more erratic and unpredictable.”

The reasons Harrison cites for the eventual split are revealing about exactly where their priorities had drifted to by the end of the 2000s: Noel reportedly leaking stories to Sun journalists, Liam incensed at having to pay market rates to advertise his Pretty Green fashion label. Beyond this, their success in the singles chart had finally ended, with both ‘The Shock Of The Lightning’ and the inadvertently self-commenting ‘I’m Outta Time’ underperforming, while the CD era that was so forgiving to their filler-loaded albums was closing. I saw Oasis on their final tour in 2009. Even as an eager to be pleased 15-year-old on a coach trip, once the opening song rush had worn off, I remember thinking that the set seemed to go on forever. On getting home, my clothes were so sodden in other people’s piss – which came raining down over the Heaton Park field in bottles throughout the entire experience – that I had to take off most of my clothes before being allowed inside my house to shower. Watching Oasis live in 2025 will be a more expensive pleasure than it was then.

Harrison presents an itinerary of the Gallagher feud as it darkened across the 2010s, as cringeworthy and banal as anyone else’s family disputes, all late night uncle-posting and shared WhatsApp screengrabs. But the dynastic Gallaghers began to get along and, post-divorce, a Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds co-headline tour with Garbage was, according to Harrison’s book at least, sufficiently humbling to bring the elder brother to the peace accords.

Yes, it is obviously about the money. But what kind of money are we talking about? The gross over-financialisation of live music was brought about by Ticketmaster’s merging with Live Nation the same year that Oasis split, and they are coming to claim their share of what has happened in the interim. Oasis: Live 25, Harrison writes, is a chance to build “truly generational wealth”. And not just from the shows themselves. This year, Noel Gallagher’s song publishing rights revert back to him from Sony/ATV. Should he wish, the songwriter will be able to sell his back catalogue in what would be the single biggest payday of his life. The reunion tour shores up the premium, illustrating those song’s appeal across a portfolio of global markets. Suddenly, it’s less Sopranos, more Succession, where fratricide can always be put aside for the next episode’s boardroom move.

In the 2020s, Oasis matter largely because successive generations have decided that they matter. Their music is passed down and endures in a way that is rare. Consumed on streaming, where their songs become atemporal and untethered from context, Oasis are finally liberated from their own decline. But the job of music writing is to have a perspective on this, to make that context vivid and prod it for what it might reveal about the music and its creators.

In this case, Oasis is a family saga of ambition, greed and escape. It takes in post-war Irish immigration into England, Greater Manchester under Thatcherism, and a set of songs written on an acoustic guitar in the storeroom of a building firm becoming, decades later, enormously bankable financial assets. It’s also a cautionary tale about being too heavy with some kinds of ambition and too light with others, about understanding when to stop, and what happens when people push on past that point. The story continues this summer. Someone would, you might think, want to write a book about it.

A Sound So Very Loud: The Inside Story Of Every Oasis Song Recorded by Ted Kessler and Hamish MacBain is published by Pan Macmillan. Live Forever: The Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Oasis by John Robb is published by Harper Collins. Gallagher: The Fall And Rise Of Oasis by PJ Harrison is published by Hachette