You can be eight and realise that England is a bitch. It takes you a little longer to realise how that bitch can fuck you over, problematise you forever. White skin so pure. Black skin so pure. You? Denied cool. Always the wannabe. The way Pakis get portrayed by the English in my still-unfolding formative years is always somehow needy, wanting in, fatally and comedically unable to be cool. And that was only when we weren’t simply invisible, in the press (apart from the usual ‘issues’/’problems’), on the telly, on the radio.

That comfort in inconspicuousness was not the way my parents raised me. They were cool, they stepped off, let me read, let me a little loose from the strict career-minded strictures that made so many of the other Asian kids me and my sister met seem so weirdly part of some pre-program, armed with futures that simply didn’t interest us. They allowed me the breathing space to learn that you can either get angry and sad, or angry and proud, and you’ll often get both. The dawning discovery that that crinkle-cut chip on my shoulder and this pain in my heart are touchstone, launch pad and dead-end inescapable.

I hit the Marathi stuff hard in the mid-80s partly because of the sheer grain of it – it’s scratchy and atmospheric in an era in which I find it hard to like the sounds bands are making. In the Live Aid years (which is a sound doubtless being rehabilitated as I speak, some earnest defender of big ‘orrible echoey drums and a whole mess of fretless fuckwittery posting ‘It Bites’ videos long into the night) I go backwards in all music. Un-hiply, I listen to nigh-on purely 60s and 70s music for two years instead of Nik Kershaw & Climie Fisher (sozboz), and what current Indian pop I hear in the 80s is just as shite as the western pop it’s ripping from. So yeah, I’m engaging in nostalgia for an India that perhaps never existed, the scratching search for roots when your DNA is forged 5000 miles away from your birthplace. A growing realisation that I don’t even feel at home being an Asian, because Asians I know beyond my own family have a sense of community, meet up, large groups, places and spaces and surety.

In contrast, we’re seemingly a community of four, eight at a stretch if you include blood-tied folk from London. The language my parents speak, Marathi, is spoken between them and them only. When we go to Foleshill, Cov’s main Asian area, hearing my mum twist her mouth into the consonants of Hindi and Urdu even I, remorselessly and lazily uni-lingual, can tell the difference. In India I’d be living in a state of 100 million people, the second most populous in the country. In England, Maharashtrians number nearly-none in the 70s and 80s. We weren’t part of that wider influx of Gujaratis from Uganda that had Enoch frothing at the gob, although the hatred he touched on has shadowed me my whole life.

Happy 80s kid

In the 80s I don’t walk down the streets of Foleshill or Longford in Cov feeling at home. Sure I feel safer, I feel like I and my skin can disappear, I don’t feel folk crossing the road to avoid me like I do everywhere else, but I know I don’t belong there either, know I don’t see my family’s curious features mirrored anywhere. The A to Z of fear that is created deep inside your brain if your black or brown is getting fully mapped out for me, the streets you can’t go down, the places you can’t walk in, the unofficial lines of segregated geography that are laid down young and stay forever. Sure, maybe paranoia but racial paranoia is at least, safety. I can walk into the Standard Music Centre, the Asian-record shop down Foleshill road and feel as alienated as I do in HMV or Our Price but I can feel unnoticed, I can sit in the barbers getting my chrome dome shaved drinking heavy sweet cardamom tea and listen to the conversation and not understand a single word but for once not feel under observation.

Race, when you’re one of only about five Asian kids in your entire school, is important, creates and moulds your consciousness and the cut of your jib in a vintage disappearing way. Gives you a conflicted sense of wanting to vanish and wanting to make as big a noise as possible, hide out and try and figure out who the fuck you are/stamp your greenhorn incongruity on the cosmos. There’s a small rack of Ustad Bismillah Kahn & other raga maestros in the music shop. That’s where I go. The medallion-man clichés of the Bollywood soundtracks that cover the walls leaves me absolutely cold, as they still do. Don’t get me wrong, Bollywood still churns out great pop now but it could be from anywhere, made by anyone, piped into any Starbucks in any city on earth. In the midst of the 80s I can hear that its aspirations and parameters are becoming almost entirely westernised, entirely globalised. I can hear it losing the universality and strangeness of old Marathi cinema-song, losing its unique prehistoric suggestions and unmediated wonder. So just as I’d rather listen to the Velvets and the Stones and Kent Stop Dancing comps while the 80s rolls its Burtons sleeves up and backcombs itself into grisly aspirational shapes.

By 1985/86, in contrast to the clear commercial space that Bollywood pop is ravenous for, I opt to lose myself in those old tapes, that old classical vinyl. Because it keeps yielding a sub-cellular glow I can’t explain which you could call ‘belonging’, a racial memory that cuts beyond language. Something to do with the beats, with the fact that Marathi movies of the golden age so often fantasised a rural Maharashtrian idyll that my parents, like so many of their generation, had abandoned for a city life in Mumbai or even further afield. The pictures are out-of-synch and so is anyone who escapes the world they were born to, to step and stumble out into another.

Out of synch as is anyone who’s walked on these black beaches barefoot and finds themselves grown up and trudging through a substance called snow that they’d only read about before.

Born out-of-synch. Because ‘Indian’ culture as perceived by the English is either hidden or horrific by then, bar the odd gem precisely those pale imitations and painful malapropisms of contemporary western pop that the west loves so much, the camp failure of all these Bengalis-in-platforms trying to look like they belong on the dance floor where it’s unlikely they’d make it past toilet-attendant. I don’t need that neediness cos with the Indian music I hold close in my juvenile 16-year-old fogeyness there’s no attempt to ingratiate, only the instant ability to fly, to be yourself where that self is free, where your eyes hurt because you’ve been waiting for god too long.

As part of a minority you’ve always got too much on, frequently too much on your mind, an extra level of negotiation with yourself and others that simmers and seethes along with everything you do. It’s exhausting. When I listen to these songs in the decade that made me both more sure that part of my life vengeance against prejudice, yet more unsure of exactly how that inner-volcano could be safely unleashed, I try and imagine how my parents listened to these songs the first time. In the village, surrounded by jungle (ironically when I listen to Ustad Allah Rakha Kahn or V.S Jog I hear jungle-d’n’b prefigured polyrhythmically), travelling cinema set up amidst the trees and snakes and monkeys and these astonishing songs coming singing through the thick forest air.

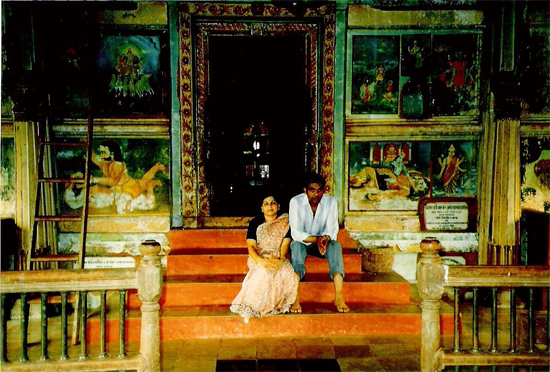

My parents outside the ancient village temple, Kasheli, Maharashtra

In 1982 I go to that jungle, seen what I dreamt, hear and feel the astonishing hum and energy of that place, dodge army ants and snakes and lizards, tie strings to dragonfliess tails, notice I am never stared at yet feel terrified in the roaring Mumbai streets, come home to Cov shaken and shocked at my own precarious identity and able to realise that yes this city of Coventry is my home but I should never ever talk race with the white folk, they simply will never ever get it. An opinion unshaken even now. Let me talk to you. Once you’ve stopped shaking.

Me, 10 and my big sister,13, at the edge of the jungle, Ratnangiri district, Maharashtra