More from Kevin "Sipreano" Howes at Voluntary In Nature

Thanks to the mentorship of OG Vancouver hippie, photographer and legendary psychedelic record dealer Ty Scammell (RIP), I’ve been collecting off-the-grid Canadian vinyl for 20 years now. Ty not only helped to shape my musical aesthetic, he also taught me to dig deeper than the Top 40 Can-con cannon – Gordon Lightfoot, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, The Guess Who, Anne Murray – to find sounds, and subsequently stories, beyond my wildest imagination. This journey has taken me across this vast country looking for abandoned regional recordings as well as the opportunity to interact with the wide spectrum of people that inhabit this land. Such exchanges have taught me about Canada’s often brutal past, which informs much of who and what we are today.

On a lighter note, this journey has also seen my car stuck in 18 inches of thick Prairie mud, rescued by members of a local Hutterite colony, almost arrested outside a derelict record store/hair salon in the middle of the night, and 15ft up in the air at a mouldy record and book warehouse sifting through unsorted boxes of 45s on a precariously thin ledge. All for the love, I say!

Early on in my career as a DJ, journalist and reissue producer, I realised that the only way to learn more about the records that I held so dear was to go straight to the source, to the music makers themselves, for without their immense contributions to our collective cultural fabric, we’d be much poorer in spirit and soul. Reaching out to many of my musical inspirations was an opportunity to thank those artists whose work had affected me profoundly, and to ask for much-needed context of days gone by. I started picking up records by indigenous artists about 15 years ago and it didn’t take long to realise that Canada’s aboriginal music makers were not only a key part of their regional and traditional communities but, in many cases, trailblazers of a thriving movement that is little-known to most outside of the greater indigenous or folk music scenes. I felt it was important to help raise awareness of this decisive era and its engaging soundtrack. Though a project of this nature can only scrape the surface of what existed back in the day, Native North America Vol. One: Aboriginal Folk, Rock, And Country 1966-1985 has bridged generations, cultures, and eras of technology in the process, something that doesn’t happen enough in today’s fragmented society. As humans, we have a lot to learn from each other and I look forward to more positive exchanges ahead. PEACE.

1. Willie Dunn (Mi’kmaq/Scottish-Irish)

At the dawn of the 1990s, my high school history teacher screened a 16mm print of Montreal-born singer-songwriter and filmmaker Willie Dunn’s award-winning short from 1968, The Ballad Of Crowfoot. Featuring a stark montage of handpicked 19th century archival images, contemporary newspaper clippings, and Dunn’s devastating song of the same name, the film focusses on the life and times of Crowfoot, a legendary Plains Blackfoot leader. It affected me intensely. I later learned that Crowfoot was one of the first National Film Board (NFB) films directed by an indigenous filmmaker.

As the 1990s progressed and I started to travel across Canada looking for vinyl records to DJ, an early catalyst was Dunn’s self-titled Willie Dunn LP (1971), on the short-lived Summus Records label (which also released Wishbone, the Canadian debut of Jamaican keyboard king and reggae innovator Jackie Mittoo). The liner notes on the back of the album mentioned that Dunn, who had served in the Canadian Armed Forces for a spell during the 1950s, had exchanged his rifle for a guitar, an equally powerful tool for a man of such grit. Unapologetic, open and righteous, Dunn’s words and music empowered and inspired First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people (he was often described by the NNA V1 musicians I spoke with as, "our Leonard Cohen"), and taught non-aboriginals about the history and current conditions of native people throughout North America. Dunn lived hard and fast, but always expressed a sense of joy and humour before his untimely passing in August of 2013. After one listen to the scathing ‘I Pity The Country’, you’ll be scratching your head as to why the songwriter isn’t mentioned in the same breath as Bob Dylan. That’s something that I hope to remedy with an anthology of Dunn’s music and film, currently in production as part of Light In The Attic’s Native North America series.

2. Willie Thrasher (Inuit)

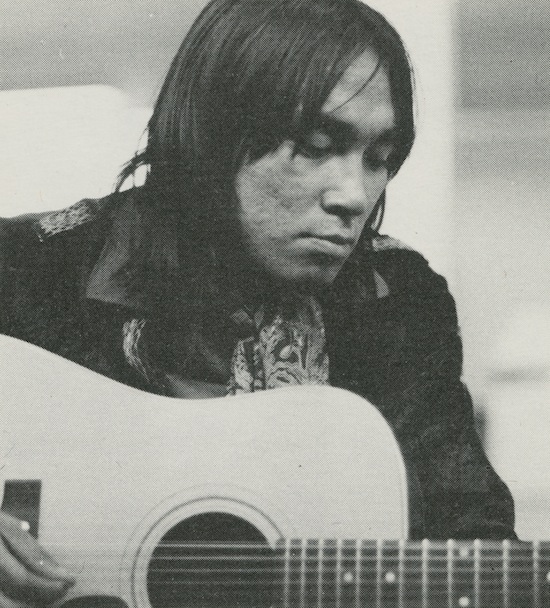

Despite finding a copy of Willie Thrasher’s 1981 Spirit Child LP in a used record store bin some 10 years ago, it was a more recent YouTube revelation which informed me this journeyman singer-songwriter is still alive and kicking. The 2009 clip shows Thrasher performing ‘The Eagle Is Calling You’ during a shift at his day job as a city-sanctioned busker in the oceanside town of Nanaimo, British Columbia. Thrasher is a community fixture in the Vancouver Island community and engages passersby young and old with his outgoing personality and songs about indigenous life from a northern perspective. Though Thrasher was born in Aklavik, Northwest Territories, he was taken away from his family at an early age and sent to a series of residential schools, part of a federal government initiative to assimilate aboriginal peoples into non-native society. Students were forbidden to practise their culture and language, and in many cases they were physically abused. Not surprisingly, the effects from this tragedy are still felt today. Thrasher, who came from a family of 21 children – including Anthony Apakark Thrasher, whose 1976 book Skid Row Eskimo is as harrowing as they come – took solace in music.

After paying his rock & roll dues in the mid 1960s as a drummer for The Cordells (an early Inuit rock band who were known for playing covers by The Beatles, The Kinks, and The Rolling Stones), writing original music was a way of reconnecting with his elders and Inuvialuit culture. Unfortunately, a work accident took off a good portion of his left middle finger in the late 1960s and forced Thrasher to find new ways to play the guitar. Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, he took to the road, working odd jobs, writing and performing at Native Friendship Centres (pivotal meeting places for First Nations, Métis and Inuit people) across Canada. Thrasher recorded his debut single with help from the Department Of Indian Affairs And Northern Development and followed it up with ‘Spirit Child’ for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (Canada’s national broadcaster, akin to the BBC or NPR). He also fell on tough times and lived on the streets for a spell. Clean and sober for 12 years, Thrasher now performs with his partner Linda Saddleback and things are looking bright for the veteran troubadour. He is invigorated by the NNA V1 project and plans to record and perform in Canada and internationally in his own inimitable style. Willie Thrasher has much to share.

3. Shingoose (Ojibwa)

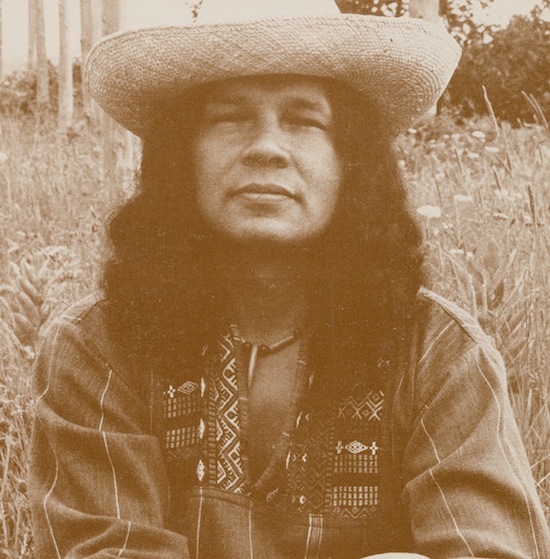

On the mainstream Canadian pop culture landscape, singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn (‘If I Had a Rocket Launcher’, ‘Lovers In A Dangerous Time’, ‘If A Tree Falls’) is as visible as they come. Outside of indigenous music circles, Shingoose is far less prominent but of no less importance. In 1975, Bruce and ‘Goose collaborated with poet Duke Redbird on the 1975 Native Country 7" EP, a fundraiser for the Native Council Of Canada. Featured on NNA V1, ‘Silver River’ is a trance-inducing fragment of psychedelic folk that’s guaranteed to take listeners to another reality.

Shingoose was born Curtis Jonnie in Winnipeg, Manitoba, but his early years were spent on the Roseau River reserve. As a teen, he moved to the United States and started making music in a variety of combos. By the late 1960s, his Washington, DC-based power trio Puzzle had garnered enough regional support to warrant a recording contract with ABC Records and studio time with the legendary Eddie Kramer (Jimi Hendrix, Electric Lady Studios). After Puzzle’s LP flopped at the shops, ‘Goose moved back to Canada and, affected by the events at Wounded Knee in 1973, started to write music that tapped into his native being. Another example of ‘Goose’s work from the era is a previous collaboration with Redbird is the 1974 film The Paradox Of Norval Morrisseau (NFB), a look at the life of Canada’s most celebrated Indigenous painter.

Working on stage and in film while continuing to record, Shingoose lived life to the max. Unfortunately, in 2012, he suffered a serious stroke and is now confined to a wheelchair. I visited with ‘Goose last December in Winnipeg and took him out on the town in search of a bag of sacred herbs. It was -15c outside and my rental car trunk was barely big enough to fit his chair. Still, the goods were procured and on our way home we noticed a sundog in the sky. ‘Goose was telling me about his plans to record a final album and I couldn’t help but feel emotional, knowing the blood, sweat and tears that went into creating his music and art. Here’s to the next chapter.

4. Duke Redbird (Chippewa/Irish)

Born Gary James Richardson, poet, artist, and activist Duke Redbird was raised on the Saugeen First Nation reserve. Equally inspired by his native heritage, classic European writers and those of the American beat generation, Duke started writing and performing in the 1960s. He also formed a group called Abundance To Revolution with iconic singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn and Penelope Schafer. Soon, Duke was taking stages by storm across Canada and the United States, often in collaboration with Shingoose, Cree singer-songwriter Winston Wuttenee and good friend Willie Dunn. Offstage, Duke made himself known as a passionate native advocate and activist, involved with everything from Toronto’s experimental Rochdale College to the Native Council Of Canada, where he acted as vice president in the mid 1970s. Duke has been profiled in books (Red On White: The Biography Of Duke Redbird) and he’s also written them (Loveshine and Red Wine).

In more recent years, he has been involved as an aboriginal advisor/mentor at the Ontario School Of Art And Design (OCAD) in Toronto. It was here that I reached out to the man himself while putting together NNA V1. With so much knowledge and experience, Duke was very helpful – it was an honour to spend time with him in Toronto last year to help raise awareness for the compilation. Duke graced us on stage at a NNA V1 awareness gathering in Kensington Market and left the crowd in awe as he recounted firsthand stories of the legendary Yorkville coffee house scene and being rooming house neighbours with a young Joni Mitchell in the 1960s. It’s an inspiration to see Duke still pushing ahead with such style in 2015. Don’t miss an opportunity to see and hear this poet laureate and renaissance man live, but be warned, if Duke offers you a game of pool, there’s a good chance that he’ll sink the eight ball before you. If the match takes place in Toronto, he might even do it on a hand-painted table that he illustrated himself.

5. David Campbell (Arawak)

Although Guyana-born singer-songwriter David Campbell is prominent on YouTube – his Marakakore channel has over 300 videos – he was very difficult to track down in person. Lucky for me, we both currently reside on the east side of Vancouver. Our first meeting took place at a local coffeeshop and we spoke for hours about David’s lengthy career.

David first moved to Canada in the mid 1960s to work in broadcasting but soon heeded music’s overpowering call. Still, it wasn’t until a move to England that David made an even bigger splash, when the influential Transatlantic label signed the young folk singer. In the late 1960s and early 1970s he also cut records for Decca and Mercury – all worth seeking out though very difficult to find – before heading back to Canada where he began work as a prolific independent artist, releasing a constant stream of albums, singles, cassettes and CDs while performing across the country on the folk festival circuit and at community gatherings large and small. While ‘Pretty Brown’, David’s signature song, continues to touch hearts around the world, NNA V1 features a lesser-known gem from the Campbell songbook. Originally released on his Song LP from 1978, ‘Sky-Man And The Moon’ features a twist on traditional native storytelling and the prominent use of synthesizers, played by Toronto jazz arranger and session player Jimmy Dale. In addition to music and visual art, David is also an active photographer. As we said goodbye after our first discussion, I watched the veteran trailblazer walk down the street for a moment. It was a beautiful sunny day outside with the local North Shore Mountains prominent in the background. As he strolled along, I could see David snapping pictures of the trees and leaves. A consummate creative, David Campbell lives his art and his art reflects his ever-so-passionate life.

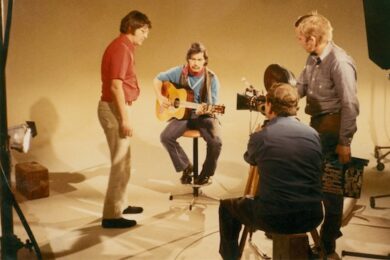

The author crate digging

Native North America Vol. One is out now on Light In The Attic