The Proms are on for the 124th time and if, like me, you’re an anorak who goes to a lot of them, or listens live on Radio 3, you’ll know that the two-months-long festival is perhaps the most misunderstood of all British cultural institutions. The general perception is that it’s something to do with cod-patriotism – waving plastic Union Jack flags and bobbing up and down to old English songs. Those things have become traditions of the Last Night – the Last Night only – and they’re largely the fault of easily the cheesiest man to have had anything to do with the festival: Malcolm Sargent, or Flash Harry as he was known, the philandering chief conductor of the concerts from 1948 until 1967, when he died.

As Paul Kildea sees things in 2007 book The Proms: A New History, “The Proms is historically the most subversive undertaking in British art music,” and there are two things in particular that make it such a revolutionary event. From its founding in 1895 (at Queen’s Hall, London, which was destroyed in World War II) to today (at the Royal Albert Hall, mostly), seats in the stalls are removed and a promenade created in their place, giving the festival its name. Standing tickets to watch music from the promenade are the cheapest, meaning those who pay the least get the best view. Secondly, no one needs to book in advance. Up to 1,350 standing tickets can only be bought on the day of concert, and it’s these democratic principles that tell you more about the true spirit of the Proms than anything that happens on the Last Night. It’s the people’s classical music festival, built upon subversive ideology, and it’s become the scene of subversive acts – mostly mild in nature, but not always.

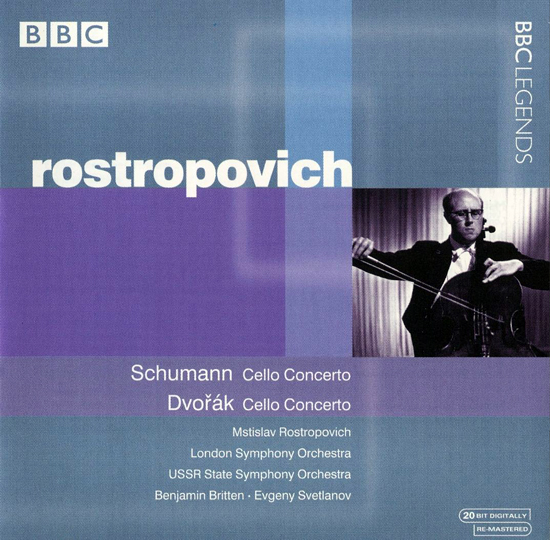

Sometimes, difficult new music provokes a reaction. In 1912, the world premiere of Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Orchestral Pieces was met by “emphatic hissing” as The Daily Mail reported, and a 1969 Peter Maxwell Davies piece, Worldes Blis, fared worse – causing stamping and a walk-out by some Prommers. At other times, politics gets into the mix. In 2011, 30 pro-Palestinian protesters demonstrated outside the Albert Hall before a performance by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, then sneaked into the arena and chanted anti-Israeli slogans to the tune of Beethoven’s ‘Ode To Joy’. They succeeded in forcing the BBC off the air, which is more than activists managed on 21 August, 1968 – perhaps the most notorious day in the history of the Proms. A BBC recording of one of the three pieces played that evening was released on CD in 2002 and it’s quite something – the most emotionally powerful live performance of classical music I’ve ever heard.

On the morning of 21 August, 1968, the world woke up to news that thousands of troops from five Warsaw Pact nations – the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and, to a lesser-extent, East Germany – had stormed Czechoslovakia, killing 137 and quashing the Prague Spring. The invasion caused international outrage and, at the height of the student protests, sparked immediate demonstrations within the Soviet Union and beyond. In London, activists lucked out. That night, the USSR State Orchestra, on their first tour of the UK, were due to make their Proms debut and some bright sparks noticed. Even better: one of the world’s best and most famous musicians – Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich – was booked to perform the only cello concerto written by Anton Dvorák, a nationalist Czech composer. It was a total fluke of circumstance.

The Prague Spring was a short-lived period of political liberalisation in Czechoslovakia – an Eastern Bloc state until its dissolution into the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 1993. The reforms were being implemented against Moscow’s wishes by First Secretary Alexander Dubček, who had come to power in January that year on a promise of “socialism with a human face”. His programme was being noticed abroad, and being covered in the press, including by British-Pakistani writer, Tariq Ali, then the editor of radical newspaper The Black Dwarf. He became a key organiser of the Proms protest. “It’s not their fault – we know that,” he said about the Russian musicians in a 2007 Radio 4 documentary, The Prom Of Peace. “But it is an orchestra funded by the state and we have to show our anger.”

Ali, with others, first arranged a demonstration outside the Soviet Embassy in London, and then the activists moved to the Albert Hall, where, under the watch of the police, they handed out leaflets, walked around with placards declaring communism to be Nazism and tried to persuade Prommers to boycott the event. With the seats sold out in advance, some had queued overnight for standing tickets, possibly in vain. No one knew whether the concert was going to take place until an hour before showtime, when, flanked by the KGB, the musicians arrived, only to be pelted with scrunched-up newspaper, and possibly also oranges and tomatoes, according to some reports.

The orchestra was horrified by their reception, but not surprised. “We were terribly ashamed about what had happened,” cellist Arkadiy Budanitsky told the BBC. “The mood changed entirely when we heard this news, and we knew of course that the reaction to our concert, and the way that our concert would be received, would be completely different. This was the first time the Symphony Orchestra of the Soviet Union had come to London to play and everything had been ruined by the fact that troops were marching into Prague. We felt very sad.”

By Ali’s count, there weren’t many protestors – 150 to 200 – but they were noisy, and some had managed to buy Promming tickets, which took the protest inside the Albert Hall. Demonstrators shouting, “Russian murderers!” and “Get out of Czechoslovakia!” clashed with those who wanted the orchestra to play without distraction. Booing was met by counter booing, raising the temperature in the hall. “As we went on stage a terrible row broke out,” Budanitsky recalled. “People were stamping, clapping, and shouting – they wouldn’t let us start playing.”

The Prom began with the orchestra, conducted by Evgeny Svetlanov, playing the overture of Mikhail Glinka’s opera Ruslan And Lyudmila. According to the cellist Julian Lloyd Webber, who was there, “Svetlanov came on and did the fastest performance of Ruslan And Lyudmila I’ve ever heard – ridiculous speed.” No recording survives but it’s been reported that the performance silenced the crowd. And then, down the route to the stage being guarded by KGB agents, who some suspect may have been armed, emerged Rostropovich, primed to join the orchestra as soloist on the most famous Czech concerto of all time. The shouting started again.

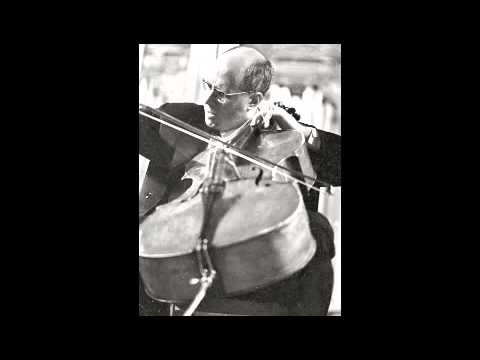

It’s hard to think of a classical musician in the second half of the 20th century who was more rambunctious and joyful than Mstislav Rostropovich – Slava, as he was affectionately known. A motor-mouth, boozer, carouser, bear-hugger and three-cheek kisser of everyone from presidents to ordinary folk working in concert halls, he was a magnetic life-force off the stage and on, and by many people’s accounts the greatest cellist who ever lived. He had, the conductor Colin Davis said, “that grain of genius and prodigious energy that, combined, makes a great musician”. As required, he could play with profound sensitivity or untamed, near-brutal savagery, and single-handedly he dramatically expanded the repertoire for all cellists that came after him. Composers adored Rostropovich. Over 100 works were written for and premiered by him, including Benjamin Britten’s Cello suites and Cello Symphony, Prokofiev’s Symphony-Concerto, and both cello concertos by Shostakovich, who said of him: “What I value most of all in his playing is the intense, restless mind and the high spirituality that he brings to his mastery – a phenomenal virtuosity combined with a noble and ravishingly beautiful tone.”

Rostropovich relationship with Dvorák’s Cello Concerto went back to the beginning of his career. In 1950, aged 23, he’d won the Hans Wihan Competition playing the piece in Prague, a city he loved. (He met his wife there – the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya – and married her four days later, after, he said, “three wasted days”.) In 1952, he first recorded it, with the Czech Philharmonic conducted by Václav Talich and he’d had a hit album with it in the UK later that decade, alongside the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Adrian Boult. It had become his signature piece, and now he had to perform in an impossible atmosphere, eyeball-to-eyeball – as the promenade dictates – with a hostile crowd.

“For him going on stage was really an act of will,” his biographer and former pupil Elizabeth Wilson says in The Prom Of Peace. “He felt like he was putting his head on the scaffold. He knew that people would be judging him just for being a Soviet citizen, so somehow he had to overcome this prejudice through his instrument – through playing the music with all his soul – and to somehow share his feelings with the audience, and to conquer the audience.”

The recording of the performance – the only recording from the night that survives – is doctored. You get a sense of the commotion in the hall before the piece starts, but in actuality the shouting continued over the opening bars. Frustratingly, a passage from a different, commercial recording has been inserted to clean up the sound, but only before Rostropovich himself comes in after the piece’s epically long, three-and-a-half-minute introduction. He hits the opening note hard, and then wobbles. His playing is initially freakish, rushed, nervous, until he locks in and sets off on what one colleague in the USSR State Orchestra said was “probably the greatest performance of his career – certainly of that piece of music – and I played it many times with him in many different cities, on many different tours. But on that occasion he played it so feelingly, so movingly, so dramatically, so tragically.”

Rostropovich wept as he performed and then, as Budanitsky recalled: “Slava raised Dvorák’s score above his head. He picked up the score from the conductor’s stand and held it above his head. He wanted to prove our solidarity with Czechoslovakia – with the Czech people, with Dvorák’s music.”

It was an astonishing moment that flipped the protest on its head. He’d begun the performance as a victim of the demonstration, and ended it aligned with the sentiments of the activists. But he was playing a dangerous game. If, as Tariq Ali said, “We argued that it’s extremely important the musicians know what we feel, because when they go back they will tell other people that there is a great deal of anger at what happened,” Rostropovich was risking becoming a marked man in the eyes of the Soviet regime. His fate wasn’t exactly sealed that night at the Proms, but his notoriety rose. Then, two years later, at his country house near Moscow, he bravely decided to shelter Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, below, writer of the anti-Soviet 1962 novel One Day In The Life Of Ivan Denisovich and winner of the 1970 Nobel Prize in Literature.

When Rostropovich started out in the late-40s and early-50s, he was both a darling of the Soviet art scene and an advocate of its teachings and strivings for excellence. Hugely charismatic and cunning, he also worked the system to his advantage, managing to live luxuriously in the Soviet Union, travel freely and record on labels in the West. Moscow thought of him as an example of Soviet superiority, and also a cultural ambassador – so long as he toed the party line.

But there were clues to Rostropovich’s distaste for artistic censorship stretching back to his days as a music student in Moscow. When, in 1948, Shostakovich – a ‘formalist’ composer in the eyes of the authorities, who was writing music “organically alien to the people” – was dismissed from professorships in both Moscow and Leningrad, Rostropovich, aged 21, quit the conservatory in protest. And he also ran close to the wind by forming a friendship and working relationship with Prokofiev, likewise a ‘formalist’ suffering persecution from the state.

The authorities might also have ignored Rostropovich’s friendship with Solzhenitsyn if it hadn’t become known that he’d drafted a letter defending the novelist and complaining that artistic talent was being suffocated by the state. The letter was never published, but word got out and Moscow stepped up their campaign against him. Concerts were cancelled, recordings suppressed and his friends turned against him, too – avoiding contact and refusing to defend him in public for fear of being persecuted themselves. He was still allowed to teach at his legendary Class 19 in Moscow, but he was being unpicked and controlled, and it almost destroyed him. “They hurled him from great heights down to the ground,” his wife says in the 2011 BBC Four documentary Rostropovich: The Genius Of The Cello. “I watched him simply fading away. It could have ended very badly, in catastrophe. In Russia you usually drown your sorrows in the bottle, become a vodka addict, and then…”

Instead, he applied for a permit to work abroad, which – to his surprise – was granted. Flat broke, he landed in London with his wife and two daughters in 1974, then moved to the States, where he became the musical director and conductor of the US National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC. In 1978, a year after he’d said about his homeland, “I will not utter one single lie in order to return, and once there, if I see new injustice, I will speak out four times more loudly than before,” his Soviet citizenship was revoked. He spent 16 years in exile, but he flourished in the West – becoming a celebrity dissident, and rich enough to buy a Stradivarius cello. In November 1989, immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he gave an impromptu concert there, which made international headlines. Two months later his citizenship was restored.

Of all the crazy stories about Rostropovich, and there are many, perhaps the most bonkers is what happened in 1991, after he saw news footage of tanks rolling into Moscow during the Soviet coup d’état attempt by hard-line members of the Communist Party appalled by the programme of reforms being implemented by new head of state, Mikhail Gorbachev. Without telling his family, he bought a plane to ticket to Japan, via Moscow, got out there and headed to the Russian White House to help Boris Yeltsin defend it – not literally, but he understood that if people knew he was there it might somehow help. And he was photographed at the White House, first with the two men assigned to guard him, then holding the gun of one, who slept on his shoulder, exhausted after having been awake for over 30 hours.

My favourite story about Rostropovich, who died in 2007, also involves a flight to Japan. As well as Dvorák’s Cello Concerto, he’d also made something of a signature piece of the prayer-like Sarabande from Bach’s Cello Suite No. 2. He played it as an encore at the 1968 Prom, and at many other times to console those feeling sad, including for his friend Chiyonofuji Mitsugu, a champion sumo wrestler. In 1989, he heard that Chiyonofuji’s infant daughter had died, so – again without telling anyone – he flew to Tokyo from Europe with his cello, took a taxi for an hour and a half to his house, set up on the street outside and played it. Once finished, he got back into the taxi, which had been waiting for him, returned to Tokyo airport and flew back to Europe.