VOTE NOW!

BLACK ON BOTH SIDES: ANGUS BATEY ON JAY-Z

The original concept of a "black album" appears to have been where an artist self-censors their catalogue, and shelves or withdraws a body of work that they’re either dissatisfied with: or, if the hype machine is to be believed, they believe to be too disturbing, depressing or accursed to release. Others are called black albums because of their enigmatic (lack of) sleeve art, a trend pioneered by no less an outfit than Spinal Tap. Jay-Z’s black album is something else: for starters, it’s actually called The Black Album, and it was conceived from the outset as its maker’s last record.

Let’s think about that for a moment, because Jay’s stated decision to retire from making music in 2003 was, for those who believed it, astonishing. Here was one of the giants of rap, a guy who’d lived the quintessential American rags-to-riches redemption story as he’d left street crime behind and had come to dominate pop culture in well under a decade. True, his seventh album – The Blueprint 2: The Gift & The Curse – hadn’t hit quite the same heights as its universally acclaimed predecessor, the first Blueprint, but it was still a chart-topper and had sold several million copies. Biggie and 2Pac were dead, Eminem was big but clearly still on the rise, and while Nas may have been declared the winner of the ‘Ether’ dis war, Jay was caning his nemesis in the charts: in their respective first weeks at the end of 2002, The Blueprint 2 sold three copies for every one of Nas’s then new LP, God’s Son. There was nobody bigger in rap, and though the internet was starting to have an impact on the stratospheric sales levels seen through the 90s and on into the new century, there was no genre selling more steadily and widely in America, by far the world’s biggest music market. Rap is often – and both understandably and correctly – compared to boxing, but there’s never been a heavyweight champion who didn’t carry on for at least one more title fight past their peak. Look at any sport and it’s hard to find an instance of a top player stepping down before they start to fade. In music, the tendency is for artists to keep on recording until they drop dead. No matter where you looked for comparisons, this was pretty much unprecedented.

So was the plan for the album, which was to see Jay collaborating on 12 tracks with 12 different producers. This didn’t quite pan out as intended, with two from the originally mooted list – Dr Dre and frequent Jay collaborator DJ Premier – conspicuous by their absence. Three other producers who’d worked with Jay before – The Neptunes, Just Blaze and an up-and-comer by the name of Kanye West – got two tracks apiece on what became a 14-track release. But Jay approached the writing with a concerted sense of purpose that had never gripped as tightly a hold of him before. Even on the tracks where the theme ostensibly strays from the sense of autobiographical closure and the need to etch his name into the annals of musical history (the Neptunes-produced ‘Change Clothes’; the criminal’s warning to rivals that makes up ‘Threat’) there’s a determination to achieve a kind of permanence that fair knocks you backwards.

For the most part, though, The Black Album is Jay at, simultaneously, his most raw and uncompromising, his most personally vivid, and – we have to assume, despite what was to happen later – his most honest and introspective. This is never less than fascinating and at times he reaches a transcendence that elevates the album into the very highest class of recordings. The pinnacle of his writing – an Everest at the heart of this musical Nepal – comes on ‘Moment of Clarity’, the second of his collaborations with Eminem. It’s telling that, unlike the Blueprint track ‘Renegade’, the Detroit emcee chooses not to get on the mic this time: it’s Jay’s show, and the material is intensely personal – there is no room here for another rapper, not even to formally allow the retiring king to hand the crown to the young pretender in public. Instead, we get Jay using Em’s beat as his confessional, returning to a theme he began to explore on the opening track, ‘December 4th’ (named for his birthday), of how his absent father’s death, and his apparent guilt at his lack of grief, had shaped his early life. Then there’s an astonishing second verse, the like of which does not exist anywhere else in pop music, where Jay matches the truth-telling and soul-baring about his private life with something just as shocking about his public one:

"The music business hate me ‘cos the industry ain’t make me

Hustlers and boosters embrace me and the music I be makin’

I dumbed down for my audience and doubled my dollars

They criticised me for it, yet they all yell ‘holla!’

If skills sold, truth be told, I’d probably be,

lyrically, Talib Kweli

Truthfully, I wanna rhyme like Common Sense

But I did five mil – I ain’t been rhymin’ like Common since

When your cents got that much in common

And you been hustlin’ since your inception

Fuck perception – go with what makes sense

Since I know what I’m up against

We as rappers must decide what’s most important

And I can’t help the poor if I’m one of them

So I got rich and gave back: to me that’s the win-win

So next time you see the homey and his rims spin

Just know my mind is workin’ just like them

(the rims, that is)"

You could call it self-serving, positing (as it does) Jay as a magnanimous hood benefactor, turning his admission of prioritising commercial success over artistic honesty into something that has a higher purpose than personal gain. But it’s still shocking today, 13 years and hundreds of listens on from its original impact.

The Black Album also rises above most other records of its (or indeed any subsequent) era in rap by ensuring that the cast of producers aren’t just roped in for name-recognition value. These are collaborations in the truest sense. Eminem’s patented blend of doomy synths and whipcrack drums never sounded more apposite than it does here, underneath and around Jay’s unburdening. Rick Rubin reinvents as he references his rock-rap roots on the brilliant ’99 Problems’, cowbells and crunching powerchords jousting with Billy Squier’s ‘Big Beat’ while Jay gives belated chapter and verse on the Lance ‘Un’ Rivera assault. Kanye loops up Max Romeo to give Jay the perfect chance to chase the devil, not out of Earth this time but perhaps out of The Planet (as some of its denizens refer to Brooklyn). Though he’s not credited anywhere on the album, kudos has to go to The Roots’ ?uestlove, who helped compile the list of producers for the record and whose sense of the cyclical nature and internal forces of influence within rap’s specifically complicated, sample-based history is writ large throughout the project.

There are occasional problems, of course, as there are bound to be – what fun would perfection be? – but most of them can be either excused or easily overlooked by a listener concentrating on finding things that work. Jay’s mum’s contributions to ‘December 4th’ never feel entirely comfortable or convincing, though you don’t doubt her sincerity so much as her evident lack of experience with public performance. ‘Change Clothes’ is frothy, but has weathered well; so has the tougher ‘Dirt Off Your Shoulder’, which you can’t decry in terms of its widespread impact after it allowed a future president to court the youth of America while dismissing criticism from his rival on the campaign trail. The record can also feel a little like it stutters, due to how so many of these songs would have worked best as the final track: the first line of ‘December 4th’ is "They say they only really miss you when you’re dead or you’re gone/ So on that note I’m leavin’ after this song"; the magnificent ‘What More Can I Say?’ ends with an exhausted, gasped expletive and the sound of Jay dropping the mic; ‘Moment of Clarity’s chorus, with its references to all his previous albums, adds something tombstone-like to what was already the quintessential Jay-Z swan song. But it’s the perfectly pitched, technically adventurous ‘My 1st Song’ that wraps things up beautifully: "Treat my first like my last and my last like my first/ And my thirst is the same as when I came."

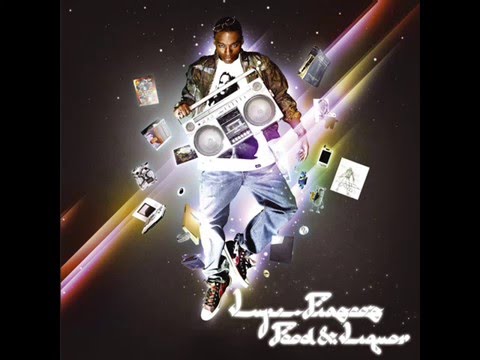

Of course, the only thing wrong with The Black Album is what happened next. We perhaps all expected that he might make the occasional foray back in to the vocal booth to guest on other people’s records – and if he’d continued to drop verses of the quality of the one he contributed to the superlative ‘Pressure’ on protegee Lupe Fiasco’s first album, we’d all have been delighted that big homie had come out of retirement. Instead, and with the crushing sense of inevitability of a Scarface fan gleefully yet ruefully proclaiming that although he thought he was out they pulled him back in, Jay broke his vow and started making albums again. Many listeners always suspected this had been part of the plan at the time: and even if it was – though there’s nothing that amounts to evidence that’s surfaced to date to support the theory – the amount of damage this does to The Black Album is, to this writer at least, minimal.

Yes, there have been moments since where the old magic shines through, and no, he’s still never made a duff album. But it’s hard to argue there are that many moments in the post-retirement phase of his discography that truly rank with the best of the work he did up to this self-imposed career break. Give a Jay-Z fan a blank CDR and ask them to fill it with their selection of his best tracks, and there won’t be many who find a lot of space for stuff from Kingdom Come, The Blueprint 3 or Magna Carta Holy Grail. American Gangster standout ‘Roc Boys (And the Winner Is…)’ is right up there with the very greatest moments in rap history, and that album as a whole has weathered better than the rest, standing today as a far cleverer, more focused, intellectually and creatively questing collection than many of us realised when it was new. But the second coming of Jay-Hova hasn’t been anything like as compelling or as accomplished as he was before he hung up the mic. And that first flush of writing and performance reaches its zenith here, on what is surely the best of the "black albums" out there.

To vote with Angus send an email to comps@thequietus.com with "JAY-Z" in the subject line

BACK IN BLACK: HARRY SWORD ON METALLICA

If James Hetfield was a town crier in nineteenth century Cleethorpes he wouldn’t shout ‘hear ye’ and ring a little bell. He’d scream ‘Heeeaaaayyyyyaaahhhhhaaahhheeeyyyah’, fire a gun into the air, take a swig of whisky and not tell anyone the poxy news.

He’d then get into a painted wagon. And in the back of the wagon would be Lars Ulrich but – now the Western frontier, not Cleethorpes – he would be a wild eyed drunken prospector wearing half moon spectacles; his sweaty face would be streaked with dirt and his eyes would gleam and he’d be holding a greasy map showing ‘gold’ and ‘oil’; and he wouldn’t stop taking about gold and oil – like a man possessed he would talk about gold and oil.

Kirk Hammett would be in the Metallica western wagon too – but he wouldn’t really say very much. He’d sit looking debauched in his glad rags, perhaps wearing some kind of laced bonnet – and he wouldn’t have slept for days – and he’d also be wearing gloves and he’d fix Hetfield with an icy glare and say something like, ‘When do we arrive, James?’ And Hetfield would just say, ‘Darn it, Kirk!’

And driving the wagon would be Jason Newsted and he’d be dressed like an undertaker. Fixed jaw; eyes flickering; nostrils flaring; saying nothing at all; just chomping his teeth and frowning deeply and driving his horses deeper into the desert with steely resolve, past the cactuses into a warm wind – the undertakers wind.

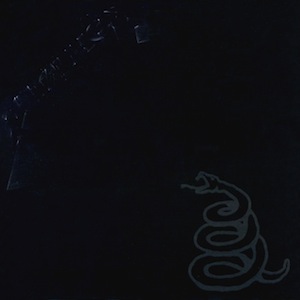

The Black Album is a swaggering beast of a record; a lumbering swampdog paddling through backwater mists with an eye on snagging the elegant flamingo. And while it’s easy to associate canonical albums such as this with a kind of idle complacency – a standing slack jawed in Tesco flicking through UNCUT before doing the shopping kinda vibe – The Black Album isn’t actually that record at all.

Rather, it represents Metallica at their loosest, grooviest and most ludicrously powerful – a slab of life-affirming class, laden with glee and driven by sheer gnash.

The brief for the record was, apparently, simple: it had to, finally, capture the power of the band live – something that had not been accomplished to any serious degree thus far. Because although 1984’s Ride The Lightening and 1986’s Master Of Puppets had come close, they both suffered from a reedy high end production job (and the occasional ragged performance) that detracted from the ultimate power of the material. Until The Black Album was recorded, Metallica had often sounded piped out of a long thin tube. To give some context: by 1987’s …And Justice For All the situation was absurd. Imagine the harshest 1980’s cocaine tinnitus mix-down taken to grotesque levels; some fictional frizz haired, medallioned imp of an engineer wearing short shorts and headband and sweating profusely; frantically hoofing up poodles legs at five minute intervals; legs jiggling up and down on a swivel chair; shakily reaching for the desk every time Newsted stepped up and turning him all the way down.

It was a record with no discernible bass at all and although it saw Metallica breaking onto increasingly big stages, the mean and waspish production was unbecoming of a band that should have been making records that sounded like a dark forest in Maine ripping up its own roots and stomping over frozen lakes while laughing at the yellow harvest moon.

Clearly, it was a situation that needed rectifying and on The Black Album Bob Rock was the producer tasked with working up the low end. The resulting album didn’t so much draw a line in the sand – both for Metallica and metal as a whole – as cleave apart the actual desert floor with a vast bejewelled sabre. This was assuredly not thrash metal. Setting aside the NWOBHM, punk and Motorhead talismans, Bob Rock marshalled a newfound sense of groove that emphasised simpler arrangements and meaty swing in equal measure.

And while it may be tempting to state that the album sounds ‘effortless’ in its primordial pendulous rumble that would be churlish – namely because it doesn’t. It sounds like the result of hard work; an exercise in forensic fat stripping. Indeed, in a 1991 interview with Rolling Stone, Hetfield stated that it took the band ‘twice as long to make a record twice as loose’.

‘Enter Sandman’ is a case in point: a single, incessant riff that doesn’t stop for the duration. And while at this point the song is an absolute co-ordinate point for modern metal, one that has spread far and wide and been canonised outside the genre – almost to the point where that riff basically says ‘metal’ to the wider public – it bears remembering that this was a seismic shift for Metallica – at the time, for them, it was the single most extreme record that they’d made. Gone were the frenetic tempo changes and dizzying classical arrangements. ‘Enter Sandman’ hinged on that one simple riff, vamped infinitum while Hetfield sang of nightmares and sprites. A deeply silly song but gloriously so, ‘Sandman’ was a Tap-esque cartoon that played with notions of the ‘dark’ in the most wilfully unthreatening way possible – a camp fairytale.

Musically, it was a huge statement of intent. The monstrous swagger was taken to epic levels. Imagine a mythical being named ‘The Lumberlunken’ made up of the stout souls and calloused bodies of fallen lumberjacks in some remote region of backwoods Canada that is taken to roaming the deserted forest on a starlit night leathered on moonshine; that is the level of swagger we’re talking about here – and it runs as a steely thread through The Black Album.

This newfound elephantine gait is present on ‘Don’t Tread On Me’ – a live favourite that hinges on belting rhythmic turbulence and dunderheaded rumble; it’s present on ‘My Friend Of Misery’, co-written by Jason Newsted and featuring the most propulsive bassline on any Metallica record; it’s even present on the two power ballads ‘Nothing Else Matters’ and ‘The Unforgiven’ – both driven by Lars Ulrich. And while his drumming may be divisive – it is by no means metronomic – his playing on The Black Album is a thing of rare drama, and afforded real prominence by Bob Rock. It carries a childlike quality, sometimes sitting just behind the beat but always hitting so hard that, even in subtle passages, it is laden in gurning gaiety.

We’re going to end on ‘Sad But True’ though. This is what I want you to consider while casting your vote. This is the song I want front and centre in your mind. It’s the crunchiest song that Metallica ever wrote – the crunchiest song that anyone ever wrote: a cleaving leviaslab of staving crunch; a concave thunder brunt of corking goliathwack.

That riff. That riff. You know it.

You know it. You know you could vote for this album on that riff alone. Just on the merit of ‘Sad But True’. In fact, I’m asking you to do exactly that.

Ask yourself this. How does listening to ‘Sad But True’ make you feel? Listen to it and then go and listen to the other Black Albums – the one by Jay Z and the one by Prince (The Sex Imp). Is there a single moment, a single solitary passage – on either of them – that compare in true visceral power and joy with the opening of ‘Sad But True’. Truthfully, is there? If so, please cast your votes for them.

But look down – deep down – into the burning vestige of your mortal soul and I think that we both know the answer. Do the right thing.

To vote with Harry send an email to comps@thequietus.com with "METALLICA" in the subject line

NONE MORE BLACK: SIMON PRICE ON PRINCE

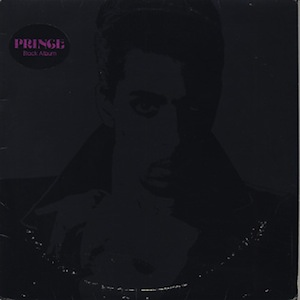

In 1987, Prince was pissing genius. And yet, from almost the moment The Black Album was completed, Prince treated this latest manifestation of that genius like it was piss.

Officially, the record had no title at all, just a plain black sleeve and the catalogue number WX147. Unofficially, it has two: as well as The Black Album, it was originally trailed as The Funk Bible. Both are instructive as to Prince’s intentions. Prince’s ‘blackest’ album for some time (perhaps ever), it was a conscious attempt to reconnect with the African-American audience who had been alienated by his pop success.

That, at least, is the dominant interpretation. Because, with The Black Album, almost everything is subject to conjecture and guesswork. The bare facts are as minimal as the album’s sound and artwork itself. WX147, attributed cryptically to ‘Somebody’ on Warners’ release schedule, was to be given no promotional campaign, and would be marketed directly at dance clubs.

It was originally scheduled to go on sale on December 7, 1987, but the plug was mysteriously pulled a week before release date. In an instant, The Black Album joined the pantheon of Great Lost Albums, sitting alongside The Beach Boys’ Smile and Bob Dylan’s Great White Wonder as one of popular music’s most sought-after unreleased records, and became the biggest-selling bootleg since Dylan’s, shifting an estimated quarter of a million in the seven year window of its contraband life. In 1991, Gord Erickson of Arizona paid £6,500 for one of the 26 ‘official’ CDs that Warner had sent out. Less wealthy – or crazy – fans had to content themselves by handing over £20 (pocket change now, but an investment which gave you pause for thought in 1987) for a vinyl copy, of depleted sound quality, from a shady retailer in Camden Market or similar. Despite the muffled fidelity, In the UK alone it shifted 30,000, nowadays enough to make it a Number One album.

But whose decision was it to shelve the album at the last minute, and why? Inevitably, in the light of Prince’s famously sour relationship with the label, which eventually deteriorated to the point of him appearing in public with the word ‘SLAVE’ written on his face, conspiracy theories have emerged that it was Warner who pulled the plugs. Rumours that the label were shocked by the album’s uncompromisingly sexual content, described not-inaccurately by Barney Hoskyns in his book Prince – Imp Of The Perverse as ‘so wantonly obscene it makes Dirty Mind sound like The Jackson Five’, aren’t entirely implausible. Especially given the growing censorious power of the PMRC (Parents Music Resource Center), the pressure group nicknamed the Washington Wives, who were formed in direct response to an earlier Prince song, the masturbation-fixated ‘Darling Nikki’ from the Purple Rain soundtrack album.

Furthermore, putting it on hold made commercial sense from at least one angle: singles from Prince’s previous album Sign ‘O’ The Times, released in March the same year, were still charting (‘I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man’ had just gone Top Ten), and Warner understandably feared market saturation. Prince had already been delivering albums at a rate of one a year, and his rate of creativity was speeding up, filling his fabled Vault with more songs than it was realistically feasible to release. The run-up to Sign ‘O’ The Times was littered with abandoned projects such as The Crystal Ball, The Dream Factory, and Camille, a vehicle for a new androgynous, helium-voiced alter-ego (as heard on ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’). There were some at Warner who felt that it was a case of quantity over quality. Marylou Badeaux, a friendly face at the label, was invited to Sunset Sound studio in Los Angeles to hear one of The Black Album tracks, but was underwhelmed. She warned him about over-exposure, and later said that “for every one great song he wrote, there were ten kind-of-okay songs”. Even his own camp had misgivings along similar lines: loyal studio engineer Susan Rogers later argued that “it may have been better if he recorded about one-fourth as much as he did.”

It seems far more likely, though, that Prince himself made the call. One version has it that he was annoyed about the record company’s pressing plant giving priority to Madonna’s You Can Dance remix album in the lead-up to Christmas, which doubtless was a factor. However, one persistent story seems to hold the key to the mystery.

With only days remaining before The Black Album‘s release, Prince experienced a ‘dark night of the soul’ which he later referred to as ‘Blue Tuesday’. On 1 December 1987, Prince gatecrashed the DJ booth of Rupert’s nightclub in Minneapolis, wanting to try out a few Black Album tracks with a club crowd. While wandering through the audience, he met a young poet called Ingrid Chavez, who he invited back to his Paisley Park studio. According to this version, which has been confirmed by Revolution keyboardist Matt Fink (who heard it from eye witness Gilbert Davison, Prince’s bodyguard), it soon became clear that Prince was in the grip of a bad ecstasy trip, and began behaving strangely. Chavez had reportedly told him, “If you smiled, you’d be a nice person.” Biographer Ronin Ro, in Prince: Inside The Music And The Masks, describes how, ‘facing his black album cover, Prince saw his miserable reflection’, and had a revelation.

Convinced that The Black Album was an evil force, he summoned Susan Rogers to the studio, who arrived to find the building lit only by flickering candles, and was met by a saucer-eyed Prince demanding to know if she loved him. (She told him she did, and knew that he loved her too, but declined his request to stay the night.) At some point, he phoned Karen Krattinger, general manager of his production company, and begged her to put a halt to The Black Album‘s release with days to spare, telling her “We’ve got to stop this album, it’s so evil.” Krattinger called colleagues Alan Leeds and Steve Fargnoli, who in turn phoned Mo Ostin at Warner pleading for the album to be scrapped. 500,000 copies, already loaded up onto pallets in warehouses waiting to be shipped out, needed to be destroyed. (Inevitably, some escaped, and the bootleg trade began, prompting Prince to flash up a subliminal message in the video for ‘Alphabet St’ reading, “Don’t buy The Black Album. I’m sorry.”

The Prince camp announced that the album was withdrawn for personal reasons. “I was very angry a lot of the time back then,” he would eventually explain, “and that was reflected in that album. I suddenly realised that we can die at any moment, and we’d be judged by the last thing we left behind… I didn’t want that angry bitter thing to be the last thing. I learned from that album, but I don’t want to go back.” Drummer, backing singer and former girlfriend Sheila E confirmed, “He couldn’t sleep at night thinking about 10-year-old kids believing, ‘This is what Prince is about – guns and violence.’” He would later blame The Black Album on an entity called ‘Spooky Electric’, the demonic flipside to his angelic Camille persona. To make matters stranger, in 1991 he told USA Today that he’d had a vision in a field with the letters G-O-D hovering overhead. He also told Gilbert Davison he’d seen Satan.

Drug-fuelled breakdowns, religious hallucinations and split personalities: had Prince actually gone mad? Was he now the full Cracked Actor, with a fridge full of piss, living off milk and red peppers? Whether or not things were quite that extreme, the truth behind The Black Album‘s cancellation – Warner’s idea, or Prince’s? – is probably a combination of the two possibilities. Prince, for whatever reason, did have his last-minute freakout, but Warner were nevertheless relieved, and pulping half a million records was a hit they were willing to take, if it meant Prince might deliver something more commercially viable next.

The making of The Black Album was spread over an 18 month period. Some tracks were essentially solo recordings, some were offcuts from other projects, and some were recorded with the remnants of the Sign ‘O’ The Times band. In terms of personnel, even more than SOTT itself, it represents almost a clean break with The Revolution era. On the band recordings, Levi Seacer Jr provides bass, Sheila E plays some drums and sings backing vocals, Cat Glover guests on vocals, Susanna Melvoin and Boni Boyer provide BVs, and Eric Leeds and Matt Blistan aka Atlanta Bliss play brass. ‘Bob George’, ‘Le Grind’ and ‘2 Nigs United For West Compton’ were originally recorded for Sheila E’s birthday party in 1986, and only one track, ‘When 2 R In Love’, was brand new. This apparently patchy modus operandi does not make it unusual among his discography. The Prince albums you love? That’s how most of them were put together, too.

The album’s consistency, regardless of the provenance of the individual tracks, lies in its overall sound. The music, like the sleeve, packs a monochrome thwack in contrast to the lush colours of previous and future albums. To illustrate the difference with the album which replaced it, Jon Pareles of the New York Times wrote that ‘Lovesexy purveys melodies the way The Black Album knocks out rhythms’.

Whether the hard funk grooves of The Black Album could ever have regained his black audience is doubtful. This was 1987, not 1978. Hip hop was in the ascendant, and the idea of a large-scale black audience who still wanted to hear uncompromising raw funk music is one which largely existed in Prince’s head rather than the real world. The Black Album was barely any more likely to get airplay on black radio stations than Sign ‘O’ The Times had. If it tapped into any contemporary movement, it was Go-Go, the fairly niche Washington party-funk sound which was peaking in the late 80s, and whose audience – like that of its related genre Rare Groove – seemed to consist largely of white metropolitan hipsters.

It begins with ‘Le Grind’, a typical Prince funk jam. After laying his cards on the table, namechecking the album as The Funk Bible, boasting of his sexual prowess and threatening to steal your girlfriend, it soon descends into call-and-response cliches, but with a twist: Prince wrily acknowledges a third sex. “All the boys say ‘Yeah Yeah’ (Yeah Yeah)/All the girls say ‘Oh Yeah’ (Oh Yeah)/Now all you others say ‘Hell Yeah’ (Hell Yeah)…”

Track two is ‘Cindy C’, an audio booty call to supermodel Cindy Crawford, for whom he had an apparently unrequited boner. (You’d think a man of his status could get a message to her via a back channel, if he wanted to set up a date.) After begging, “Won’t you fuck with me?” he ungallantly implies she’s a prostitute by offering to “pay the usual fee”, but it gets stranger. “I can feel your ice is thinning/ Like a frozen pond in spring/ Your furry melting thing awaits me…” Furry melting thing? Smooth, Prince. Smooth.

‘Dead On It’, a wounded, bitter backlash against hip hop (and a parody of the genre), is probably the album’s nadir. Prince, like his idol James Brown, was an arch-traditionalist who despised rap for its perceived lack of musicality. In 1988, Brown would release ‘I’m Real’, his own takedown of hip hop acts who dared to sample his work. Of course, Brown had quite a nerve, doing this: as far back as 1975, he had effectively ‘sampled’ David Bowie’s ‘Fame’ on ‘Hot (I Need Need Need To Be Loved Loved Loved)’ by recreating Carlos Alomar’s guitar lick from that song, without crediting either Bowie or Alomar as co-composers. Prince, too, had some balls: he’d previously tacitly endorsed hip hop by licensing two Sheila E tracks, ‘Holly Rock’ and ‘A Love Bizarre’, to the soundtrack of the film Krush Groove. Also, the high-speed semi-spoken verses on his own ‘Girls & Boys’ were essentially raps, and on ‘Cindy C’, the track directly before ‘Dead On It’, Cat Glover had borrowed some lines from JM Silk’s ‘Music Is The Key’. Engineer Susan Rogers, who would quit Prince’s set-up shortly after The Black Album, thought ‘Dead On It’ embarrassing, a sign that Prince was out of touch with new developments in music, and she had a point. (Belatedly, in a spirit of if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em, Prince would hire rappers of his own.)

The next track, ‘When 2 R In Love’, is the one which didn’t feel as if it belonged on The Black Album at all: an intimate ballad, evoking a private moment between two lovers rather than a declaration in front of the rest of the world, delivered as if no-one else is in the room. It would later be rescued for Prince’s next album, Lovesexy.

Side Two of the vinyl began with ‘Bob George’, which is hands-down THE most fucked up thing in Prince’s entire catalogue. (We’re talking about a catalogue, don’t forget, which already included the controlling mind games of ‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’, a hymn to incest in the form of ‘Sister’, and in the thankfully unreleased 1982 version of ‘Extraloveable’, the lines “I’m sorry, but I’m just gonna have to rape you/ Now are you going to get into the tub or do I have to drag you?”) Over a thumping, brutally minimalist computer beat, accessorised only by some squealingly atonal guitar reminiscent of Robert Fripp’s improvisations with Bowie and the sound of automatic gunfire, Prince acts out a one-sided drama of domestic violence. In an unsettlingly deep pitch-shifted voice (a counterpoint to the sped-up Camille, leading some to assume that it’s Spooky Electric incarnate), he adopts the persona of a jealous thug accusing his woman of adultery with the eponymous Bob. (The name is generally thought to be an amalgam of former manager Bob Cavallo and journalist Nelson George.) Amid the terror, there’s a sly reference to the artist himself when it emerges that Bob’s profession is music management. “What’s he do for a living? Manage rock stars? Who? Prince? Ain’t that a bitch. That skinny motherfucker with the high voice! Please…” It’s one of the most chilling pieces of music Prince has ever recorded, and a work of stone cold genius, even if it’s difficult to listen to for pleasure.

By total contrast, ‘Superfunkycalifragisexy’ is the album’s most playful moment, a party jam with a dizzying Wizard Of Oz/Willy Wonka feel, and bizarre lyrics about bondage, masturbation and eating squirrel meat. Penultimate track ‘2 Nigs United 4 West Compton’ also mentions squirrel meat, amid chitter-chatter at the start, along with Cat talking about her ‘fuck me pumps’, and a drunk-sounding Prince trying to crash her party: “I want you to meet some friends of mine. No no no, you’ll like ’em. They’re musicians…” A piece of hyperactive funk with a callous-thumbed bass solo from Seacer, it’s so super-fast it’s almost undanceable. The title has retrospectively read as a reference to NWA, but that’s unlikely, as the track was originally recorded for an album by Prince’s pet jazz-fusion band Madhouse in early 1987, and NWA’s Straight Outta Compton didn’t come out until July 1988. At the time of The Black Album‘s (non) release, NWA’s discography consisted of one minor single, ‘Panic Zone’, which a rap hater like Prince would have been unlikely to encounter, still less to reference. Occam’s Razor points to a coincidence.

He drops down into a more human groove for finale ‘Rockhard In A Funky Place’, left over from 1986’s abortive Camille sessions. An archetypal Prince sex number, it features further daft varispeed vocals, a little musical thowback to the big guitar ending of ‘Let’s Go Crazy’, and the memorable line “I just hate to see an erection go to waste”. After the fade-out, there’s a squeal of feedback, and Prince asks "What kind of fuck ending was that?" before The Black Album fades out for good.

And what the fuck kind of ending would The Black Album have been, had it been, as Prince feared in his most paranoid moments, his last testament to the world? It’s a fair question, but a moot one, as The Black Album was quickly followed by Lovesexy, the album generally held to be the bookend of his Imperial Phase. Lovesexy is essentially Prince’s Scary Monsters, in other words the album after which most people consumed his music by cherry-picking rather than unconditional surrender. As a performer, however, he was on absolute fire: the Lovesexy tour, which I caught at Wembley Arena in the summer of 88, was utterly stunning. He still exhibited mixed feelings about The Black Album, because three songs – ‘Supercalifragifunkysexy’, ‘When 2 R In Love’ and its darkest moment, ‘Bob George’ – were included in the setlist. In the tour programme, he articulated the reasons for the album’s existence. “Camille set out 2 silence his critics. ‘No longer daring’ – his enemies laughed. ‘No longer glam, his funk is half-assed… So Camille found a new colour, the colour black… the strongest hue of them all.” (However, Camille then realises he has allowed “the dark side of him to create something evil”.)

That ‘evil’ creation eventually received a limited official release between November 1994 and January 1995, and did Prince a favour: it went some way towards freeing him from his six-album deal with Warner. But it was during its seven-year lockdown that The Black Album gained its enduring mystique and allure.

No fan, surely, no matter how contrarian, would name The Black Album as their favourite. But as a companion piece to the albums either side, it’s an essential purchase (whether legal or illegal), shedding light – or rather, shade – on the state of mind of the world’s greatest musician. This, then, is no radical reappraisal or rehabilitation. The Black Album doesn’t need that. It is what it is. Any honest Prince-lover knows that The Black Album wasn’t even the best Prince album of 1987: Sign ‘O’ The Times wipes the floor with it.

But it’s the best Black Album in history, by a clear five feet and two inches. With a modicum of respect to its dozens of rivals – not only Metallica and Jay-Z but The Damned, The Dandy Warhols, Neu!, Spinal Tap, the Beatles bootleg, even Hanif Kureishi’s novel and play – Prince, an incontinent genius at the height of his powers, pisses on all them in six-inch stack heels.

To vote with Simon send an email to comps@thequietus.com with "PRINCE" in the subject line

The winner will be revealed next Thursday. Read Quietus Competition Terms & Conditions here