Above and beyond the setlists and soundchecks, touring is tough and requires a lot of focus on the pennies and the pounds. Whether we’re talking about an eleven album deep doom-metal trio trying to make a living, or newbies who are simply trying to avoid making a loss, touring requires the construction of a web of planning, such as savvily pre-booking Premier Inns on their advance rate or deciding between four or seven hours sleep (knowing the difference is often several hundred pounds saved on cheaper flights).

Whether bands play to 500 people or 50,000, being able to predict the right number of medium-sized T-shirts to print so they don’t sell out (or get saddled with hundreds of pounds of left over stock) is boring but more important than ever.

Like any small business, understanding a profit and loss spreadsheet is crucial to live music. If you can’t get cancellation insurance due to COVID and fuel prices are continuing to rocket, every single hoodie and hand to hand record sale counts more than ever. So, aside from knowing how to impress a crowd, being able to set reasonable prices for merchandise to generate maximum sales and a decent profit, is more integral to a successful tour than it has ever been.

However, since live music slowly returned after lockdowns, artists from support band level to circuit headliners like the Charlatans and veterans like Peter Hook, have used their social media channels to call out venues for cutting into their income from selling merchandise.

Based on the reaction to tweets like this, fans have been understandably shocked and angry to learn that venues take this kind of cut. As was I when I first encountered the practice at one venue while on tour with Ed Harcourt.

“We’d like you to meet Derek, he’ll be selling your merch tonight…”

That’s very kind of you, I thought. It’s been a long drive to get here and this will give me a chance to have a walk after sound check. I also won’t need to take the float to the toilet with me.

“he’ll take 20% of all sales…”

Wait, what?!

“…and if sales are less than £50, we will discuss how he’s paid…”

We were a week into a UK tour and as a fresh faced artist-manager, who was also tour manager, driver, merch seller, in-car DJ and emotional support service, this commission structure felt quite (there’s probably a beautiful French or Japanese word for this) “unexpected”.

Having promoted gigs from an early age in my hometown of Weymouth, my false sense of confidence that I knew what the hell I was doing instantly turned into a cartoonish gulp of confusion. Panicking a little, I hugged an increasingly heavy box of 27 medium, 19 large and 10 extra large t-shirts…

This sprawling multi-million grant funded arts institution wasn’t anything like the grassroots venues to which I was usually accustomed. So I piped up, politely:

“It’s ok, I’ll do the merch myself.”

The stare I was met with by the promoter was a mixture of ‘Aw bless’ and ‘Are you serious?’ as they began explaining this was "standard venue practice" and I would have to pay the sweet looking retiree regardless, as it was in the contract, which clearly I had either not read nor understood. Usually I left such things to a tour manager, which we couldn’t afford on this lap of the UK.

There’s a lot of jargon and complexity in the live music industry and boy oh boy is there a lot of “non-negotiable” small print. Dive into that and sometimes you’ll discover an accumulation of items promoters will add to the costings of a show. This kind of practice is rare at 200-700 capacity venues, but as you step up from Hebden Bridge Trades Club and Exeter Cavern into big brand sponsored academies, iconic institutions, and theatres, you notice the ker-changes.

At many grassroots venues there’s an independent owner, who is often also the promoter. When you move up to larger venues, it’s far more likely the venue is being hired by an outside promoter (sometimes from an affiliated subsidiary company, who also seem to take some of the mysterious ‘booking fee’) and every penny from the bouncers to laundering the towels, is on a spreadsheet of show costs. It’s at this level where venues tend to charge a commission to sell merch, which is perhaps understandable when there are ten different merch points dotted around The O2 arena.

For many artists, it’s when they begin to transition to larger capacity venues as a support act that they discover not everyone is slogging away just for the music, the musicians, and the fans.

The sight of a stitched logo on a polo shirt soon becomes a red flag that someone seemingly lovely, who’s offering to hold a door for you (rather than help carry anything, obviously) has a calculator running in their head. With each box you lug in, the numbers in their eyes flick up-and-up like the digital read out on a post-Brexit service station petrol pump. Or, as Gavin Miller from WorriedAboutSatan puts it: "It reminds me of that Simpsons episode where they shoot the Radioactive Man movie in Springfield, and the mayor and police chief just gouge the film crew for stuff like ‘leaving town tax’ and a tax on ‘not wearing puffy pants’.”

After spending two years of pandemic time cooped up at home – a time when many have become even more interested in various social justice issues – many musicians have emerged increasingly suspicious of practices that have become part of the everyday “normal” of touring. Many are wondering aloud, has it always been like this, and is it time for a more equitable approach?

Perhaps a combination of Bandcamp’s no commission Fridays and all the fundraising artists did during lockdown has also made some of these business practices, which take from the artist’s cut of their T-shirts, hoodies and record sales, begin to feel even more absurd, or as Stuart Braithwaite from Mogwai puts it, “like theft”.

“Artists have fronted campaigns during lockdown,” explains David Martin from the Featured Artist Coalition. “Artists have done benefit shows, raising money for venues or for festivals. In lots of cases that money is not going directly to support artists, but it’s artists that fronted lots and lots of the stuff that supported the industry.” He continued “look at the UK’s cultural recovery fund, most of that money went to bricks and mortar businesses. It didn’t go to freelancers and it didn’t get to many in the artist community. I think some practices do feel different now.”

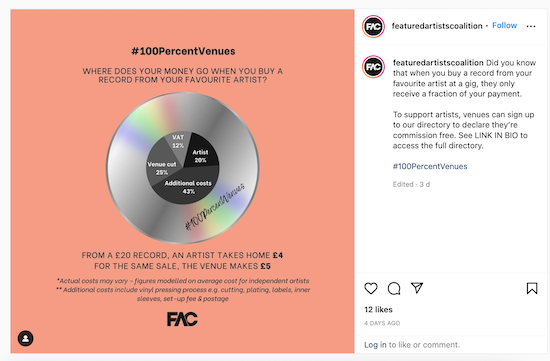

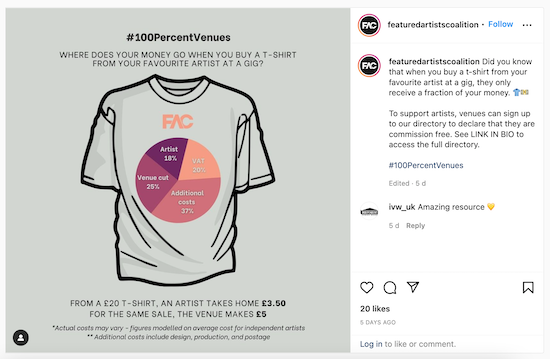

Featured Artist Coalition (or FAC for short), whose members span from acts playing their first gigs to stadium stars, have long pursued the issue of venues taking a cut of merch, but in recent months this campaign has ratcheted up, causing many venues agreeing to give 100% of the merch money to artists. Over 350 venues have already signed up to the FAC’s directory and as well as the great grassroots venues like Leeds Brudenell, The Bullingdon in Oxford and Glasgow’s Hug & Pint, there are also some bigger names making this artist-friendly pledge, like The Troxy in London.

Aside from ownership of these spaces, one key difference is that in the smaller venues, the artist or someone in their crew will sell the merch. But at these much bigger venues, it’s often (but not always) personnel provided by the venue who will staff the merch desk(s).

“Small venues very rarely ask for anything,” points out Mercury-nominated Hannah Peel, who is yet to tour extensively post-lockdown. “I remember some venues taking a 20% cut, even as the support artist, and they didn’t supply any staff or help at all. It’s challenging when you’re getting paid an absolute minimum daily rate to perform in large venues and then having to pay [an extra] commission. I was thankful to be touring solo. It’s not possible to make it work with larger groups unless [you are] subsidised by a label.”

It’s tough out there, as David Brewis of indie-pop heroes Field Music – who in the past have headlined venues like the Barbican (who recently signed the 100% to artists pledge) and Shepherd’s Bush Empire – confirms: “I know there’s an idea floating ‘round that bands make loads of money from selling T-shirts and that may be true for bigger bands but it’s never been true for us.”

He explains: “We can cover our costs and make a few quid to put in the pot but that’s about it. It’s not a money spinner. At a less well-attended show, that £30 fee for a merch seller might take us into the red. And a 20% cut from the gross makes it impossible to sell records – I don’t feel like we can charge a tenner for a CD or £25 for an LP when I know full well the cost on Amazon is two thirds of that price. Once the venue’s cut and the VAT come off, every sale would be at a loss.”

Of course, unlike Field Music, it’s easy for Amazon to dodge paying their fair share of taxes. But they’re not the only ones doing well at the moment. Confusingly, the record industry is actually booming… but for whom?

With sales of physical music up by 16.1% according to the latest IFPI report, readers might feel that this article is splitting hairs, given that things are looking up. However, there’s not much trickle down from the likes of Spotify’s Daniel Ek, who is reportedly investing $200 million in Joe Rogan, Barcelona FC and war tech rather than giving more money to musicians.

It’s not just the platforms raking in vast sums: Lucian Grainge, the head of Universal Music Group (UMG) recently received a "stonking" £123 million bonus. Meanwhile, a recent Guardian investigation discovered that UMG receives a share of Academy Music Group’s (AMG) profits from the sales of merchandise. These sales at O2 Academy venues are outsourced to company trading as Concessions Management International Ltd., which is part of Universal’s Bravado merchandise division. The report found that AMG and UMG take a cut, even if the act whose merch is sold is not signed to UMG.

For a long while, there’s been a refrain of ‘artists make their money from live’ to offset conversations about poor streaming royalties. If the record business really is now booming – the BBC reported that the global music market was worth $26bn in 2021 – not many musicians seem to be sharing in the wealth.

While platforms such as YouTube, Spotify and TikTok are great for building an audience, it likely has not slipped your attention how challenging it is to make even a few million streams turn a profit.

There are hidden marketing costs involved in generating these streams. Then the streaming income goes to a record label, who are taking anything from 50% (if they’re a nice indie label) to over 85% share if they’re a major. The standard deal structures mean that labels do not pay the artist anything until they have covered their costs (“recouped”), including the advance they essentially loaned the musician against sales to record the music in the first place. To sell CDs and vinyl on the road, artists need to procure them at more or less the same ‘dealer price’ as record shops buy them.

In short the record biz is complicated. It’s not easy to make money from recorded music, which is why artists are often living off of their Bandcamp sales (and why Bandcamp Fridays with zero commission was a godsend to artists during the pandemic, paying out $73 million to artists). Likewise, merch money earned on the road is essential to the musician’s survival, as it covers the costs of gear, visas, transport and so on.

What the cliché ‘artists make their money from live’ theory omits is the years of investment of both time and money before they earn even minimum wage from playing to 500 to 2,000 people, based on 200 nights playing live per year. And the reality is, due to the geographical concentration of fanbases and competition from other acts for ticket money, most musicians at this level only end up performing 20 to 50 shows per year.

In some cases, if the musician’s latest album has done well, some of those gigs will attract a £3,000 to £5,000 festival appearance fee. This may sound like a lot until you consider that the fee needs to be divvied up between a band, factor in the van hire (often £120 or more a day with an extra £50 to £100 on fuel), £150 to £300 for someone to do sound (in order to ensure the whole thing doesn’t sound awful after a desultory five minute festival line-check. Oh, and not forgetting the 20% booking agent commission. (Solo artists often end up paying £130 to £350 per day to professional musicians to be in their band. (There is more on fair fees for musicians here.) Plus if the musician is not doing a run of dates – it’s harder to tour between May and September aka Festival Season – they’ll need, say, a week of rehearsals to ensure their 30-minute slot is impressive. And that’s just playing some shows in the UK. Let’s not begin to get into the costs of visas to play in the USA or Europe.

After a few years off the road doing “a real job”, it shocked me to read this tweet from the manager of Belfast rock troupe New Pagans, who scored an enviable support slot opening for nineties rock behemoths Skunk Anansie at some of their UK and European shows

“The Brixton show was really confusing,” admits Belfast-based artist manager Charlene Hegarty who works with New Pagans. “Before we start, I just want to clarify, when we got the final show settlement the total merchandise concession was 25% plus VAT, which in real terms was 30% of our sales total, not 45% as had been previously suggested. However, venue commission should be an optional ‘service’ – not a profitable imposition.”

Had they not expected this, then? “Initially we were told there was no merch concession for us on any of the shows on the Skunk Anansie tour. The source of that information seemed trustworthy at the time, but as it turned out it wasn’t true. This was a major problem as we didn’t learn this until the first night of the tour. All our budgets and forecasts were now out the window.”

If you’ve learnt anything so far, it’s that budgets and cash flow are crucial to touring. Hegarty continues: “Each night, we would arrive at a venue, ready to plead or do battle on merch fees. German venues seemed to be much more understanding than other countries on the tour. The uncertainty was a real rot in our foundation as we were depending on merch fees to help us break even. Profiting was a dream we had put to bed long ago when we factored in boats, van hire, rising fuel costs, carnets and the most basic two-star hotels each night.”

“At the Brixton show, we didn’t need a seller, the band always prefer to sell their own merch and I was there to tend to the station while they played on stage. We know our own merch better than anyone.” This is something that comes up time and time again speaking to artists, especially those doing support slots, who understand that time spent selling merch is as important as the time on stage. It’s not just about upselling, it’s about making a connection to fans both old and new.

She adds: “However, the in-house merch team took our stock and the closest we could get was standing outside the merch area after the show to talk to anyone who wanted to say hello to the band. We are morally opposed to venues taking a cut but given the lack of notice or awareness of this we had no choice but to have them sell it and let them take a cut for doing so. We needed any income we could get, the show was running at a loss so the best we could hope for was to mitigate the damage.”

These commissions have become the norm. Zola Jesus told me that around world “venue merch sale cuts are such a standard part of touring now, and they can cut into our profits to such an extent that I’ve sold shirts out of the back of my tour van more times than I can count.” Like most artists I spoke with, she caveated this comment: “I understand that venues need to survive too, but it shouldn’t be at the expense of the artists.”

The Barbican

This understanding of being part of an ecosystem is something that David Martin from the FAC picked up on several times in our conversation. Whilst artists (and the network of fans that supports them) have budgets, so do venues. As well as space in the venue, staff is often provided to sell the merch. “If there’s a cost, we understand that” he says. “We appreciate that there can be costs to things, but we’re way beyond that when you’ve got 25% or 30% or 45% commission being charged. This conversation has been around a long time and it’s time it was addressed.”

Commission, as opposed to a cost, which varies from venue to venue, is being addressed by venues signing a pledge to give 100% of the money to artists. “It’s a really simple campaign. It’s a really simple ask,” he continues. “It’s self policing. A sort of fan policing because if you’re going to stick your name down then an artist will police it if then the venue start charging someone commission. And fans will start tweeting about it!”

As Charlene Hegarty points out “It’s completely unfair and we need bands at all levels of their career to stand up against it to put an end to it. Our issue is how venues have zero liability and profit richly on narrow margins.”

She explains the maths of the merch desk: “For example, on a £25 LP sale, our label take £13.20 (fair enough, they are trying to recoup their investment, we have a very artist friendly deal with a great label). The venue take £7.50, they have no responsibility for paying for stock, they are only open to profit, no risk. The band then earn £4.30. Almost half of what the venue takes but the band have all the costs to get to the show plus the years of work that goes into that LP.”

“As for tees. If we sell a tee for £15. We pay £6 to print it. The venue takes £4.50. And we take £4.50. Again the venue profit as much as we do but without any of the liability involved in the design, print or delivery costs.” It all adds up doesn’t it? Of course, if you’re a massive act the economies of scale outlined in this BBC piece mean tees get cheaper and artists can consider fair trade & eco-friendly options like vegan inks, re-milled materials, or take the risk of commissioning multiple designs without passing too much extra cost onto fans.

In an attempt to hack around escalating costs and venues nibbling away at their income, artists have found short term solutions. Dry Cleaning alerted fans using the Dice app that they would be selling merch at a nearby pub. Meanwhile, artists such as Get Cape, Wear Cape, Fly are experimenting with geo-located merch apps such as Hawkr, which gives fans a discount on their order based upon their location. Some acts will provide a "click and collect service", meaning they get their poster, hoodie or vinyl shipped to them.

Meanwhile, the 100% venues campaign carries on apace. “What we’ve found,” adds David Martin from the Featured Artist Coalition, “is that this is really pissing off fans, who weren’t aware this was happening. Our mission is to simply make things a little bit fairer. We are in conversations with some of the bigger venues and some of the bigger companies.” Will you be ramping up your campaign? David nods and confirms “We’re not going to be going away!”