In Street-Level Superstar, Will Hodgkinson’s forthcoming book in which he spends a year with Lawrence (of Felt, Denim, Go-Kart Mozart and Mozart Estate “fame”), the hard fiscal reality of being a “cult artist” (so poetic on paper, so grim in actuality) is coldly mapped out. A mix of thinly spread council benefits, benevolence and serendipity have just about kept Lawrence’s very bony chin above water for close to three decades. Bleak vignettes roll along, like Lawrence lugging a bag of “brown coins” to the bank to get a much-needed £40 in notes, subsisting on extremely milky tea and packets of liquorice or selling off treasured books and records to keep going. It’s Down & Out In Paris & London for 70s-obsessed novelty pop singers.

There is a degree of self-mythologising with Lawrence – that of the driven and singular artist navigating dire straits in unswerving pursuit of their unique vision – and that is no doubt part of the appeal for some of his fans. He is the ultimate cult artist, a watercolour curio, an Edmund Trebus of baseball caps. A thesis put forward in the book is that, as much as he talks about wanting a smash hit and money to buy houses in the north, south, east and west suburbs of London, he will always sabotage his own plans because the dream is much easier to handle than the reality.

There has long been a romanticised ideal of the starving artist in their garret, fingerless gloves on their hands, leaking shoes on their feet and sheets of ice building up on the inside of their grubby, greasy windows. Somehow, amid the grime and the squalor, there is a purity to their work. Some musicians, strategically exploiting this, have created a false backstory to lend their art a credibility and a realness they otherwise fear was absent. Or just to misdirect and take the piss.

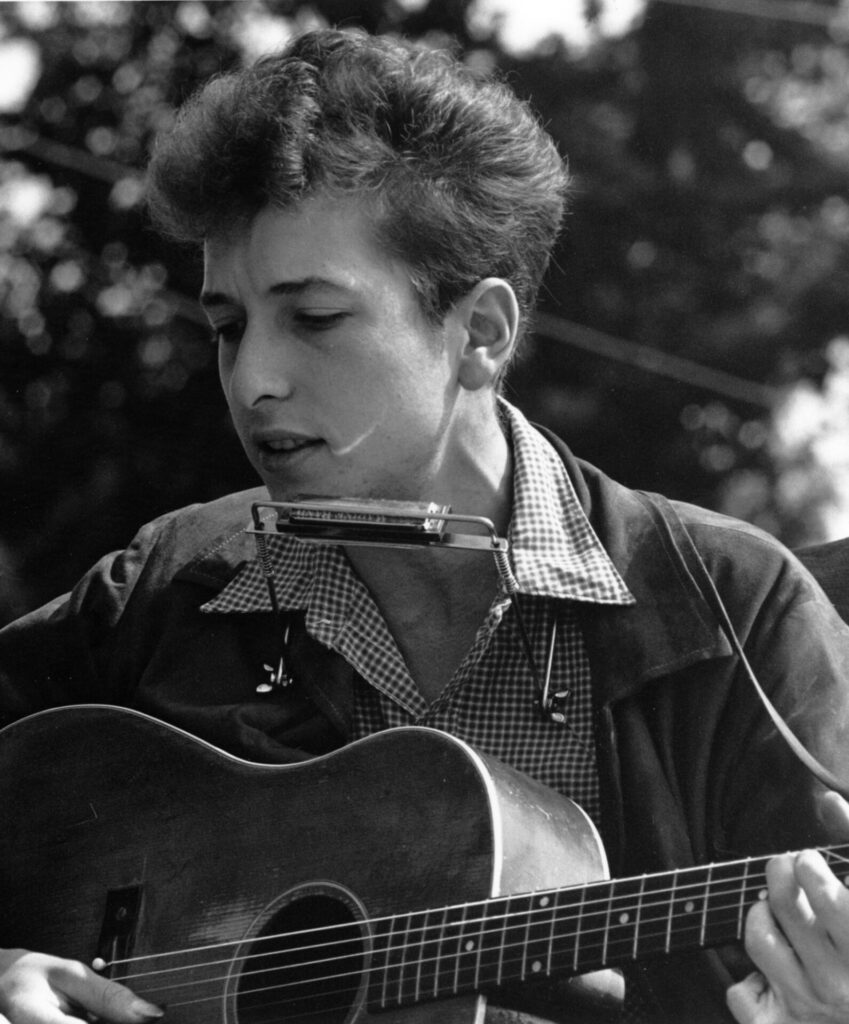

Bob Dylan, to complete his Woody Guthrie tribute act in the early days, claimed to be an orphan who had run off with the carnival. His parents, of course, were still alive at the time, his father running a furniture and appliance store. That very comfortable and stable background clearly did not fit with Dylan’s dust bowl chic “narrative” and proved to be a dry run for him spinning outrageous yarns about himself, partly as a way of shielding his private life and partly to amuse himself in interviews.

Pete Doherty, the son of a major in the Royal Signals, absolutely played up to this mythos, having skimmed Wikipedia entries about symbolist poets like Baudelaire and fin de siècle artists scrabbling amid the dirt, so hungry their stomachs started to consume themselves. This, he thought, was how real art was created. Yet instead of producing Les Fleurs Du Mal, he repeatedly rewrote threadbare versions of ‘Roll Out The Barrel’.

We also saw Seasick Steve try and cosplay as a hobo when he started his solo career, adding a decade to his age and moving to carpet over his session musician and disco past. Or there was this embarrassment of Victoria Beckham insisting she came from bold working-class stock, except when her dad drove her to school in a Rolls-Royce. In that sense they all ran ahead of themselves and took the line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance – “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” – and used it as their A&R strategy.

By presenting a hardscrabble history, the thinking goes that success and riches, when and if they come, will be seen as well deserved. Here is social mobility in action. No one can begrudge them their millions now. Yet it is the creative arts’ version of slum tourism that is shamelessly exploited as a shortcut to authenticity.

On the one hand, music fans will rail against corporate entities (Spotify, Google, Facebook, Universal Music Group, Apple) for building their brands on the creative sweat of others, accusing them of short-changing the very people who propel them to astronomical profitability.

On the other hand, audiences are far from immune to buying into the notion that great art can only spring from poverty and the underclass. In part this is why The Last Dinner Party were accused of being “industry plants” given they both dressed and spoke like they were extras at a society ball scene in Downton Abbey. There is an abstraction of thought, a cognitive dissonance, happening here, amplified by the idea that grit makes the pearl in the oyster, where some fans will latch onto the idea of poverty being noble without actually countenancing the reality of that poverty.

The life Lawrence leads is not one to ennoble, doomed to deludedly believing that the hit that can make his fortune is just around the corner when all the evidence suggests that he will never have the success that he has sacrificed family, relationships and bandmates for.

In recent years, Nadine Shah has laid bare just how hard it is for musicians to make a living. Giving evidence to the UK parliamentary inquiry into the egregious economics of streaming for most musicians in 2020, she told of how she had to temporarily move back in with her parents as she could not afford her own place. More recently, she announced she was not playing Glastonbury this year as the fee she was offered was too low to make it anything but a financial loss for her. This was compounded by the fact she was offered a slot on a stage that was not going to be televised by the BBC. Among the online comments following her breaking Glastonbury omertà on how low its fees are was this doozy: “This all stinks of the usual ‘I think I’m bigger than I actually am’ bollocks. If you were worth a prime slot, you’d have a prime slot. Tell me, who would you bump for you?”

Even more upsetting is the fact that someone has had to set up a GoFundMe for Anthony Reynolds, former lead singer of Jack and Vashti Bunyan collaborator, who is homeless. “The UK housing crisis and the stigma of being a 50 something self-employed musician/writer has made finding a new flat difficult,” explains the fundraiser. “He has no savings. Having released over 10 albums and several books, like many artists he has always lived project to project. Also, the dominance of music streaming and its notoriously pitiful royalty rate has shrunk any earnings from music and music publishing to a negilgible [sic] amount.”

The exalted image of the starving artist is often a purely academic idea that sits in our heads, utterly divorced from the traumas and the panics and the fears of those same starving artists. The idea that great art can only come from suffering is a cruel and pernicious one that is given far too much airtime.

The economic reality for most artists is, frankly, horrifying. The last thing they need is a head tilt and a patronising line about how their art will be all the better for it. Just as “exposure is not an accepted form of currency at the bank”, the hungry cannot dine on platitudes.