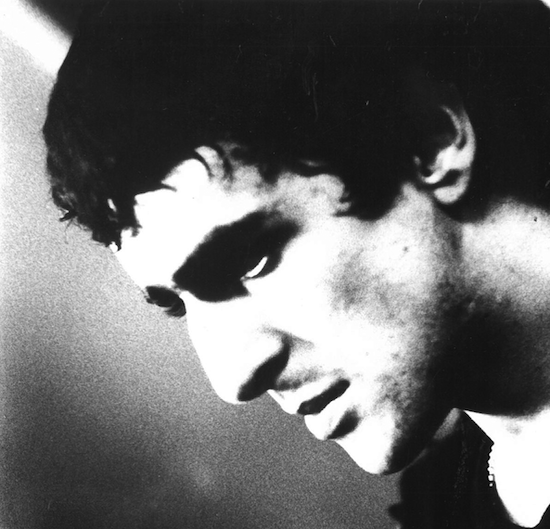

Jaz Coleman portrait courtesy of Killing Joke

It’s undeniable that Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978 – 1984 (Faber, 2005) is an essential text for anyone interested in the revolutionary potential of DIY music recorded in the pre-digital age. This weighty but gripping tome starts with the implosion of the Sex Pistols during their ill-fated American tour of 1978 and concludes with the explosion of such ‘new pop’ acts as Frankie Goes To Hollywood and Art Of Noise seven years later. These two stylistically diverse bookends only hint at the cornucopia of ragged and revolutionary sonic thrills to be had on the pages in between. The oppressive gloom of Joy Division; the herky jerky deconstructed jazz fusion of The Contortions; the militant Marxist funk of Gang Of Four; the avant feminist punk of The Slits; the revolutionary machine noise of Throbbing Gristle; the rumbling, scabrous dub of PiL; the heady, post-modern pop of Talking Heads, and so on.

Those flicking through the book could be forgiven for thinking that Reynolds has something of a blind spot for goth music however. Despite this gloomy subgenre of rock music fitting comfortably under the post punk umbrella, it barely gets a look in. The entire subject gets wrapped up so quickly that I don’t think one could be blamed for assuming that, after glam at least, he has an aversion to bands with something of a theatrical or androgynous bent. (This is not meant as a criticism of Reynolds. He remains one of my favourite music writers and his book, Energy Flash, should be required reading for anyone who fancies trying their hand at this job. Any author facing the unenviable task of providing an overview of an entire genre of music will always risk annoying some readers during the process of delimitation, narrative and focus; they simply have to place the emphasis where they feel it fits best.)

None of this should be a surprise. Goth music, in its early 80s heyday, was so astoundingly uncool that even most goth bands themselves would get annoyed if you accused them of being a goth band, so any such group of musicians wanting to assert their revolutionary musical credentials has always faced an uphill battle. While the general criticism that most of these groups were simply in hock, to glam rock, rings true to a certain degree, it is easy to accuse nearly any punk or post punk band of the same thing – and at least the goths weren’t in debt to pub rock, skiffle or earnest rockabilly as well like many of their more fashionable punk rock peers. Besides, by the close of the 1970s, any musician looking back a few years to Brian Eno’s sky-scraping solo albums was obviously still, essentially, interested in the process of breaking new sonic ground. At the end of the day it feels like this criticism is only really applied to men and women wearing heavy eyeshadow.

It’s easy to disprove any claims that dissatisfaction with the goth canon is based solely on musical grounds. Joy Division are arguably the first goth band. Paul Morley is popularly lauded as the writer who coined the term gothic, when talking about music in the post punk period, in a very early review of the group (however I’m literally now counting down the seconds until Siouxsie And The Banshee’s angriest fan emails me to explain why I’m wrong). Suffice to say Joy Division were there at the start or thereabouts and they and their extended family including Morley, Kevin Cummins, Martin Hannett and Peter Saville, partially constructed the foundations of the scene. They never suffered the same fate as any of their peers due, in part at least, to how normal they looked and behaved – post-Warsaw, at least. While only a fool would attempt to talk down the importance of the Macclesfield/Salford quartet and the stunning body of work they produced in such a short space of time, it would also be a fallacy to suggest that no other ‘gothic’ band shared their revolutionary potential.

Towering over most of their contemporaries in these stakes, Bauhaus cemented their innovation early doors. Their opening salvo, ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ (1979) was an instant composition/ free-improvised dub reggae/disco rock collision utilising the studio mixing desk as an instrument and non-standard guitar and vocal techniques, immediately placing them on a par with such self-regarding sonic revolutionaries as the Pop Group and arguably ahead of conceptually progressive funk rock group, Gang Of Four. The Leeds quartet were, of course, a revolutionary band themselves, but to me, this primarily stems from the magisterial guitar playing of Andy Gill whose exploded sheet metal soloing and rhythm work, thrillingly dissolved time in the middle of the rigid 4/4 framework. His style impacted over the Atlantic, most notably with a young Steve Albini, who was clearly making notes. But then, post punk was fucking awash with groundbreaking guitarists… John McGeogh, Keith Levene, Richard Lloyd & Tom Verlaine, Viv Albertine, Craig Scanlon & Marc Riley, Lesley Woods & Paul Foad, Vini Reilly, Will Sergeant… the full list is staggering really but somewhere near the top of the list sits Bauhaus guitarist Daniel Ash.

The mocking of ‘Bela Lugosi’s Dead’ as both being camp and dealing in obvious goth tropes doesn’t make any sense as Bauhaus were clearly a band with a sense of humour and these conventions – funereal singing, a love for vintage horror movies, an obsession with morbidity and so on – weren’t yet codified like the T-shirt selection in a Hot Topic store, this is a snapshot of them being tested out together in real time. As science fiction writer Steve Aylett says in Heart Of The Original: “True creativity, the making of a thing which has not been in the world previously, is originality by definition. It increases the options, not merely the products. But while many claim to crave originality, they feel an obscure revulsion when confronted with it. They have no receptor point to plug it into.”

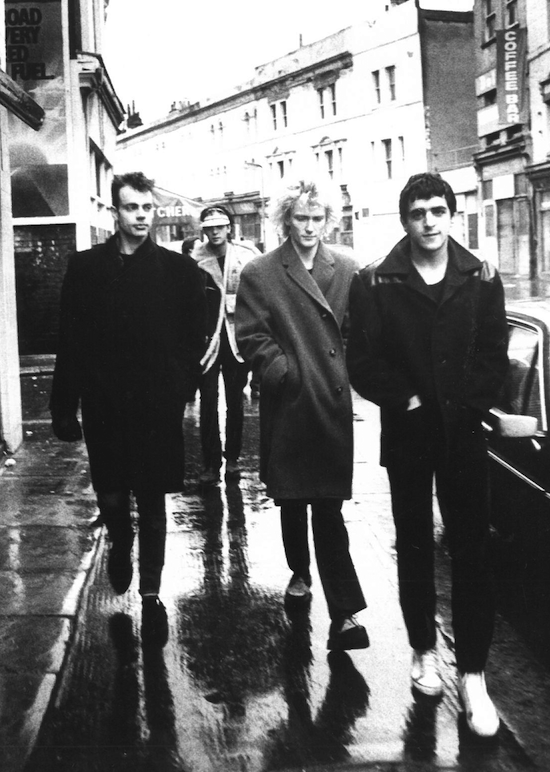

Bauhaus, courtesy of Beggars

One only has to listen to such WTF-is-going-on-here masterstrokes as ‘Rosegarden Funeral Of Sores’, ‘Double Dare’, ‘Small Talk Stinks’, ‘Spy In The Cab’, ‘Hair Of The Dog’, ‘Swing The Heartache’ and ‘Mask’ to realise that when you’re listening to Bauhaus you’re standing on some infernal continuum that links Berlin Bowie and Iggy with The Butthole Surfers, The Jesus Lizard, My Disco, Neurosis, Liars and Slint, among many others. Bauhaus were almost universally derided by the NME and Melody Maker in their day but it seems to me their major ‘crimes’ can be summed up succinctly like this: good looking, pretentious, lipstick, leather trousers, Northampton.

The same story gets played out with Pornography by The Cure, my favourite rock album of the 1980s. One of the darkest, most spiritually crushing yet psychedelic and beautiful records of the period, it was a black mirror reflection of sun-dappled Summer Of Love optimism, portraying the collapse of the ego into existential chaos set against a backdrop of 20th Century atrocity, taking the key sonic document of goth – Kaleidoscope by The Banshees – and pushing the sound up to its apogee… and yet it was treated with suspicion or scoffed at in some quarters because of backcombed hair and smudged lipstick. (The Cure are, to be fair, not universally reviled as a post punk band – they had a notable fan in the renowned cultural critic Mark Fisher who revealed a deep and sincere appreciation of their work when writing about them on his influential K-Punk blog). And so it also goes for various flashpoints of inspiration dreamt up out of nowhere by other often critically derided but genuinely outlier bands such as Siouxsie And The Banshees, the Sisters Of Mercy and The Birthday Party.

One band who seem to be more overdue a reappraisal than perhaps any other of the post punk era however are Killing Joke. Their critical pariah status is easy to understand (and, many might say, self-inflicted). They dallied with goth’s theatricality while remaining as threateningly thuggish as The Stranglers meaning their use of make-up alienated nearly everyone but their fiercely devoted hardcore of fans; their spiritual and occult leanings ran in complete opposition to the rationalist humanism of most serious music critics of the day; their eschatological and apocalyptic worldview won them nothing but derision for decades even though reality, sadly, appears to be hell bent on proving them right. They have, by some accounts, not always been the easiest or most pleasant of people to meet in person (though I’ve had nothing but good experiences on that score over the last two decades). But then, all of this stuff is mere ephemera that serves to obscure the real question: are Killing Joke originators and innovators. To me, the answer is an emphatic yes on both accounts.

Radicalised by punk in the late 1970s classically trained musician and son of Anglo-Indian parents, Jaz Coleman had a vision for a brutalising band which would summon up the spirit of the coming age of societal collapse which would emit “sounds from a primeval world”. After meeting his soon to be drummer and bandmate, Paul Ferguson, via a chance encounter in a West London dole queue, the pair hatched a plan to find two other band members using magic. They organised an occult ritual round at Ferguson’s flat which involved them painting the floor black and adorning it with a pentagram with aligned cardinal points and then conducted an arcane ceremony by candlelight. The process was either very successful or very unsuccessful depending on whether you were the two musicians or their landlord. A stray candle led to the flat getting set on fire, but not long afterwards (via the more mundane route of an ad in Melody Maker), the pair had an audition with guitarist Kevin “Geordie” Walker and bass player Martin “Youth” Glover. Their first alcohol-fuelled rehearsal led to the song ‘Are You Receiving?’ and within months they were sharing bills with Northern peers Joy Division and headlining London’s Lyceum venue.

Portrait courtesy of Killing Joke

During their entire career, Killing Joke have been an influential band – impacting hard especially in America on everyone from Metallica to Ministry via Nine Inch Nails and Nirvana. (It was obvious to anyone with ears that self-proclaimed Killing Joke fans, Nirvana, half-inched the riff to ‘Eighties’ for their massive ‘Come As You Are’ single – assuming that is, they weren’t familiar with ‘Life Goes On’ by The Damned. The circle of influence was completed in 2003 however, when Dave Grohl joined their ranks temporarily as drummer, for their high watermark Killing Joke album.) Their period of innovation however was much more compact and can handily be summed up as the initial phase that featured Youth as bass player, between 1979 and 1982. (Reynolds both criticises and lauds Killing Joke in Rip It Up for being part of the reactionary trough that came after the true innovation of Joy Division and PiL and then later becoming post punk’s answer to Black Sabbath with the release of Revelations in 1982. While I agree with the latter, very astute view I can’t with the former as it ignores the fact that Killing Joke actually hit the ground running in creative terms.)

The band’s DIY independent credentials were impeccable at the start; they released singles through their own Malicious Damage label, co-run with the artist Mike Coles. While it’s true that the band shared some similarities with immediate precursors Joy Divsion and PiL, early tracks ‘Pssyche’, ‘Nervous System’, ‘Turn To Red’, ‘Requiem’, ‘Wardance’ and ‘Change’ (plus various dub reworkings and remixes) show a group with a carefully curated sound that didn’t just incorporate stylistic flourishes from contemporary dance music but instead twisted punk rock and metal until it became primarily dance-focussed. The imperial Killing Joke sound of the mid-80s would go on to be defined by the sepulchral guitar playing of Geordie but in its initial months and years the catalyst for innovation was brought by Youth and how he interacted with the hypnotic dance rhythms of Ferguson, drawing variously on dub, funk, disco and metal as well as punk.

The heavy, three dimensional bass playing and space echo dub processing on early tracks can be attributed to Glover: after all, his adopted nickname, Youth, came from his obsession with vocal reggae chanter Big Youth. (‘Change’ particularly is a shining high point of the post punk canon, a nerve jangling, dancefloor-aimed, Nietzschean reworking of War’s ‘Me And Baby Brother’ as envisioned by LSD-enhanced occultist punks channelling the dark workings of Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Black Ark studio. This was an epochal vibe that would be leant on heavily by pre-eminent acid house post punk revivalists, LCD Soundsystem for their breakthrough single, ‘Losing My Edge’ in 2002.)

Of course one of the reasons why Killing Joke remain at the sidelines is a matter of pure unquantifiability. Reynolds himself was sharp enough to note that a hard to define “dark, tribal energy swirled round the group” and this was one of the reasons they were accused, variously, of being Nazis, nihilists, devil worshipers and just plain evil. They were none of these things however, they had simply constructed a brand new sound whose tension and intensity, stemmed in part from obsessive practice of occult ritual and locked in hypnotic groove construction. This new sound was unpalatable to most outside of their devoted fanbase. It might sound odd to mention the band’s deep interest in Rosicrucianism, the Kabbalah and Thelemic practice in relation to their status as sonic innovators but no more so than the way a working knowledge of critical theory is often used to plump up the futurist CVs of bands such as Scritti Politti, Gang Of Four and the Pop Group. Critical theory is a relatively obscure blend of Marxist philosophy and psychoanalysis which was devised by a sometimes culturally counter-revolutionary group of mid-20th Century German academics to analyse the impact of capitalism on modern life. Thinkers such as Theodor Adorno undoubtedly inspired some of the best music writing of the post punk period from the likes of Ian Penman and then later on Reynolds himself, and when they were talking about the heavily politicised groups that they favoured, this kind of framework made for an ideal pairing. Music writers of this period traditionally gravitated toward songwriters who were left wing and who wrote self-referentially about the business of making music. So when it came to describing Gang Of Four’s (excellent) Entertainment! album and its forensic look at the alienation caused by capitalism (“Down on the disco floor! They make their profit!”), writers had the perfect literary tool in the form of critical theory.

But the critical theory framework would prove itself less useful when it came to music that dealt in the numinous, the sublime, the spiritually crushing and the existentially nauseating. All of which were elements of the overwhelming Killing Joke experience. In the weekly music paper Sounds, Killing Joke’s second album What’s THIS For…! (1981) was awarded a sterling five out of five score. The reviewer also took the bizarre step of awarding the album one out of five for morality and made a point of warning readers that listening to it might prove “corrosive” to the soul. With the benefit of hindsight, such handwringing seems laughable but it was this sense of a doorway being opened to a terrifying and unmediated world outside of normal moral conventions, more than any other reason, that saw the group become more accepted by heavy metal fans than by any other community. (Which I would say is odd, for a group who began by violently thrusting together funk, reggae, disco and punk.) But the way in which Killing Joke can suggest the collapse of normal values and negative transcendence through the intensity of music alone means they have more in common with such groups as Slayer, Electric Wizard, Black Sabbath and Mayhem than they do with The Fall, Joy Division, Devo or The Raincoats.

Portrait courtesy of Killing Joke

The idea that the band could maintain this level of spiritual and sonic intensity was impossible. The tension it generated was too stressful and everyone in the group suffered because of it. While roundly mocked at the time Coleman – who has since been diagnosed as suffering from a bi-polar condition and severe depression – fearing the oncoming apocalypse disappeared to Iceland in 1982 when the band were on the verge of critical and commercial breakthrough. Youth stayed in London but was no better off for it. He had an LSD-induced nervous breakdown and spent some time in a psychiatric hospital after attempting to break into a Grand Masonic Lodge in the centre of London.

Killing Joke went on to have their imperial period – their 1985 single ‘Love Like Blood’ is one of the most fondly remembered alternative rock songs of the mid-80s and they have now survived long enough to be hailed as pioneers of “heavy music” (but not post punk). They sold out the Royal Albert Hall this weekend and have just released a new single ‘Full Spectrum Dominance’ – with their original line-up, no less. Very few bands have crackled with such intense and innovative electricity as Killing Joke did in those early years however and whether post punk scholars will recognise this or not, remains to be seen.