In 1992, a critic for Gramophone magazine, which calls itself “the world’s authority on classical music since 1923”, reviewed a recording of Rachmaninov’s popular Piano Concerto No. 3, performed by American-Israeli pianist Yefim Bronfman. It’s a fiendishly difficult piece to play, and the critic, Bryce Morrison, wasn’t impressed by Bronfman’s interpretation. “He lacks the sort of angst or urgency that has endeared Rachmaninov to millions,” Morrison wrote, adding: “Bronfman sounds oddly unmoved by Rachmaninov’s intensely Slavonic idiom. In the sunset coda of the adagio his playing is devoid of glamour and in the finale’s fugue he lacks crispness and definition.”

Fifteen years later, in February 2007, Morrison heard a version of the same piece credited to English pianist Joyce Hatto and decided it was “among the finest on record… the opening theme is given with a special sense of its Slavic melancholy… Above all, everything is vitally alive and freshly considered.” He concluded that the music on the CD was “stunning” and “truly great”.

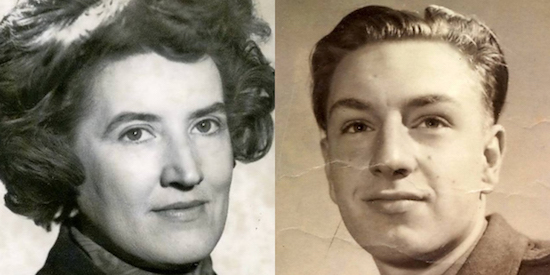

What Morrison didn’t know was that he was reviewing exactly the same recording – Bronfman’s genuine, Hatto’s plagiarised. He’d been fooled and become just one of many victims of the most elaborate scam in modern music history, which saw a decent pianist who’d had a second-rate career decades earlier enjoy an Indian summer like no other. When she died in June 2006, aged 77, her Guardian obituary read: “Joyce Hatto was one of the greatest pianists Britain has ever produced… Her legacy is a discography that in quantity, musical range and consistent quality has been equalled by few pianists in history.” And yet, the 100-odd CDs that made her name late in life, long after her first attempt at success, were fakes – copies of other recordings meticulously reproduced, and often digitally manipulated to try and conceal the fraud, by her husband, William Barrington-Coupe, who released the music on a label he’d established in the 1950s, Concert Artists Recordings.

Concert Artists Recordings. You read the name now and you spot a possible joke – Con Artists Recordings. Ten years after the scam was exposed in 2007, very soon after Morrison posted his review of Hatto’s phony Rachmaninov CD, the story does seem blackly funnier than it did at the time. It’s become a legend: the subject of a 2009 Channel 4 documentary, which played it as a whodunit, a 2010 Radio 4 feature, a BBC One drama, Loving Miss Hatto, penned in 2012 by Victoria Wood, who saw it as a love story, and it’s even inspired two novels. And I’m returning to it in this Junk Shop Classical column because it suddenly seems potent again – a kind of proto-metaphor for the world we’ve ended up in a decade later, post-experts and still seemingly unable to determine what’s real from what’s fake. Also, it brilliantly scratches at itches you get if you listen to classical music, like, what makes a good performance of a piece and who has any right to say what’s hot and what’s not?

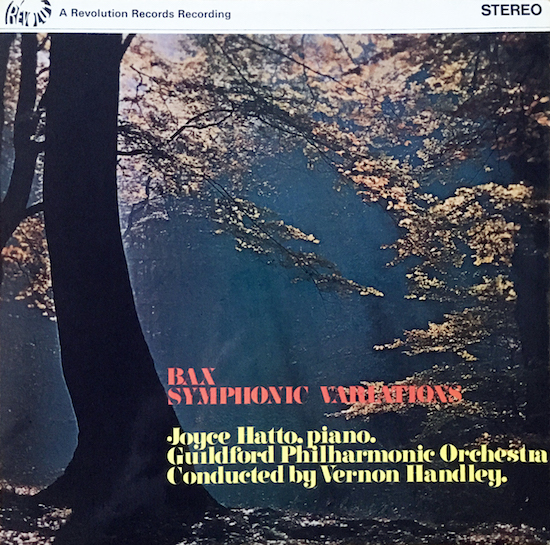

The Joyce Hatto story can be neatly sliced into two halves – the first analog, the second digital. If you find a Joyce LP in a charity shop – and they’re common – it’s her playing on the record, as indeed she did on the one pictured at the top of this article. That she had a concert career as a young woman, and released albums, helped make the later fraud believable, but it wasn’t much of a career, although she had talent and proved to be a good piano teacher, too (the author Rose Tremain was a pupil). She was born in London in 1928 to a father who was a baker, antiques dealer and piano enthusiast, and she once told the actor and critic Jeremy Nicholas that, “The only time I saw my father cry was when he heard of Rachmaninov’s death [in 1943].” She definitely said that, but whether it’s true is unclear. The web of lies she spun with Barrington-Coupe late in life make so much in her early story uncertain. She also told Nicholas that she studied with Marian Holbrooke (sister of the composer Joseph) and Serge Krish (who had been a pupil of the Italian master Ferruccio Busoni), which is possible, and knew such piano greats as Benno Moiseiwitsch and Clara Haskil. These claims are repeated in Nicholas’s Guardian obituary, which is still online, but they could just be examples of one of Joyce’s terrible weaknesses – chronic namedropping of people she’d probably never met, and were all dead, making it impossible to check.

Barrington-Coupe – Barry, to everyone – was three years younger than Joyce and started out in the music business in the 1950s as an everyman, working as an agent, promoter, A&R, label manager, sound engineer, and producer. He had good ears, but not very good business sense, and he was prone to sailing close to the wind while trying to make a living. Even as far back as then, he was repackaging music that he didn’t own the copyright for (often from behind the Iron Curtain) and selling it as original LPs with imaginary performers listed on the covers. He had fun doing that, coming up with names like Herda Wobbel, a soprano, and conductors Homer Lott and Wilhelm Havagesse. (At the time of writing, you can find releases by both of those conductors for sale on Discogs, priced between £1.50 and £8.99.)

According to a 2007 Private Eye report, Barry was also chiefly responsible for bankrupting Saga Records – a legitimate classical label that he worked for in the late-50s – after which he went into business with maverick producer Joe Meek, setting up the pop label Triumph Records in 1960. They had three hit singles, before falling out and folding the company less than a year later, leaving a run of 45s that, ironically, are now very valuable. And then, in 1966, Barry and four others were jailed for a year for tax evasion, after they imported a bunch of radios from Hong Kong and sold them via mail order and, off the back of a lorry-style, at markets in London. A Daily Mail story suggests that the trial was, at the time, the longest and most-expensive in the Old Bailey’s history, costing £150,000, and the judge summed up by saying: “These were blatant and impertinent frauds, carried out in my opinion rather clumsily. But such was your conceit that you thought yourself smart enough to get away with it.” If the judge did say that, he was perfectly describing Barry’s early career.

Barry never sought to rip off Joyce, who he married in 1956. He loved her, absolutely believed in her talent, and perhaps his biggest mistake in the early days of their relationship was promising her the world without being capable of delivering it. Acting as her agent, he did secure her concerts and record contracts, and he stood by her as they weathered decidedly mixed reviews. He put himself financially on the line for Joyce, too, presumably funding the 1970 release on one of his many short-lived labels, Revolution Records, of her recording of Arnold Bax’s Symphonic Variations For Piano And Orchestra. And although the album looks suspect, with its wacky psychedelic logo (Barry also released reggae, pop and children’s music on the label) and mention of Joyce being accompanied by the Guildford Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Vernon Handley (you can’t help but try and find a pun in his name), it isn’t a fake. The orchestra was real, and stayed in business until 2013, as was Handley, who died in 2008.

Listen to the B-side of the album

And here’s where things start to get really intriguing, because Joyce knocks a very tricky piece out of the park on this record. Bax, born in 1883 and pictured below, was a prolific British composer – a “brazen romantic”, as he called himself – best-known for writing symphonic poems and seven symphonies. By the time he died in 1953, he’d fallen out of favour, only to be revived by a series of albums recorded in the late-60s by the Guildford Philharmonic with Handley conducting on Lyrita, an excellent label specialising in British composers. His Symphonic Variations were written during the First World War and, according to the liner notes on this record, if they’re to be trusted, Joyce playing them – first at a concert at Guildford Civic Hall on May 2 1970, then at Abbey Road for this album shortly after – marked “the first public presentation of the full score since November 1920”.

Critic Tim Mahon writes on the All Music site that Bax’s Symphonic Variations require “a pianist of prodigious ability, large hands and great stamina”, and Handley was more than impressed with Joyce’s performance, saying at the height of Hatto-mania in 2006, “As a solo pianist, she was absolutely marvellous. She had 10 wonderful fingers and she could get round anything, and also she was an extraordinarily charming person to work with, even if she could be very difficult.” (After the scandal broke a year later, he sheepishly countered his comments, saying: “She had a very doubtful sense of rhythm… the recording of the Bax was a tremendous labour.”) The album also got a good review in Gramophone with critic Robert Layton writing: “Joyce Hatto gives a highly commendable account of the demanding piano part.”

We know now that this album is Joyce’s greatest musical achievement. After plenty of misfires, it could have given her a proper, mid-life career in the 1970s, but disaster struck in 1976 at a concert that Niel Immelman, a Royal College of Music professor, described in the Channel 4 documentary, The Great Piano Scam, as being, “Quite simply the most extraordinary, amazing, strange, weird recital I’d ever attended. Almost from the outset, we realised that we were in for a rough ride.” One of Joyce’s pupils, Caroline Wessel, who was also there, continued the story: “After she’d been playing for a short while, she suddenly collapsed, face down, hands on the piano, unconscious.” And in that single, terrible moment, her career was over.

A crisis of confidence? We don’t know. But it’s been speculated that Joyce suffered a nervous breakdown after the concert, forcing her retreat from public view. Naturally, Barry had a different story – he claimed that from as early as 1970, when she was recording the Bax album, his wife was suffering from the ovarian cancer that would eventually kill her, although an interview with her radiologist published in The Independent in 2007 suggested that “she was first treated only 15 years ago [1992] and had had no previous history of the disease”. That she survived cancer for 15 years is remarkable in itself; that she could have lived for more than 40 years after being diagnosed seems implausible. No matter, and as screwed up as it sounds, it was on that bed of an X Factor-style sob story that Barry planted the seeds of his giant hoax, because what kind of person would question a man whose wife was gravely ill? And, yes, Barry must have worked in cahoots with Joyce, although he always denied her involvement.

And so to the second act, which takes place in the digital realm. For a fantastically detailed account of how the scam unfolded, put the kettle on, then read Mark Singer’s monster, 11,280-word New Yorker deep dive from 2007, ‘Fantasia For Piano’, which I’m only going to summarise here. Singer introduces us to a key player right up top, a German high school teacher and fanatical record collector with exactly the kind of name that Barry might have made up: Ernst Lumpe. And perhaps if Ernst hadn’t visited Barry in 1989 to ask him for help working out whether a number of records he owned – some released on Barry’s Concert Artists label – were correctly accredited performances or stolen ones, Barry wouldn’t have come up with the idea of trying to give his wife a second stab at fame.

Throughout the 90s, Barry would send Ernst examples of Joyce’s music – then commercially unavailable and probably entirely stolen (although he might have included some genuine recordings). He was cooking up his plan, described by Singer as Ernst might have seen it: “In recent years, it seemed, Concert Artist and Hatto had quietly embarked upon a major endeavour. With Barry acting as producer, Hatto had tackled a prodigious repertoire in the studio. It was an unlikely undertaking for a woman now in her early-70s, made odder by the fact that Barry had expended little effort to market the records.” And that’s what Ernst, who believed Barry, told visitors to various online classical music chatrooms and discussion groups when he went live with his secret in 2002 – that in the small town of Royston, Hertfordshire, a story was brewing with a massive cherry on top: not only was there an unknown pianist out there who had mastered the most challenging pieces in the repertoire, recordings existed, and they were world-class.

In effect, Ernst was Barry’s portal to an online world that he may have got lost in had he tried to find his way around alone. Ernst uploaded music and Barry, from afar, monitored responses, adapting his entirely fictitious story, and adding to, if commentators raised concerns, as many did. And all the while he was creating more fake Joyce Hatto records and offering them for sale, covering his tracks with simple production tricks – possibly assisted by a sound engineer called Roger Chatterton – like altering tempos, flipping the channels and creating composite albums on which many different pianists were playing, say, Leopold Godowsky’s Studies On Chopin’s Études.

Barry, pictured above later in life, was beyond audacious. While many of the performances he stole were from little-known pianists on indie labels, we know now he also plundered some classic recordings, including one of the most famous pianists of all time, Vladimir Ashkenazy, playing Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 2 with a legendary orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, on Decca Records. And even the idea of him putting out a CD of Joyce supposedly playing Godowsky’s Studies On Chopin’s Études reeks of a man with humongous balls, or someone who was so deluded that he never thought he’d get caught: the 53 short pieces are among the hardest piano pieces to play and had only been recorded in their entirety three times before.

But Barry’s con worked. News of Joyce Hatto seeped off the message boards and into the world of classical music critics – here and abroad – who ate up the story of the cancer-ridden genius recording in a shed at the bottom of her garden. (There wasn’t even a shed.) Of course it seems ridiculous now, but neither Joyce or Barry hid from reporters or fans online – they conducted interviews, and held very good accounts of themselves, answered emails, and the scam could never have worked if Barry didn’t have a knowledge and appreciation of music that rivalled, or bettered, the professional critics that he so supremely fooled (and may have despised). “My husband is a very good critic,” Joyce said in an interview. “He has a better idea of sound than myself.” And that’s very true. You could argue that what Barry was ultimately doing was creating a collection of what he considered to be the greatest recordings of all time, as a kind of pet project that just happened to make the woman he loved famous beyond her wildest dreams. And so, as Victoria Wood realised when she was writing the script for her BBC One drama, the story of Barry and Joyce, who never had children, can be seen as a love story – of a man’s love for his wife, and their genuine, shared love of music.

When Joyce succumbed to cancer, the hoax hadn’t yet been revealed and you can’t help but wonder whether she died happy or racked with guilt and regret. She had to be in on the con, because she can’t have not noticed the CDs with her name on saying she’d recorded concertos in local churches with an orchestra (or the reviews of them). She never did that; the orchestra, the National Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, and its conductor, René Köhler, had been invented in the 50s by Barry, who also came up with entirely false backstories, which he freely offered to Hatto fans online. (He may also have cracked a good gag here – Kohler, without the umlaut mark, is the brand name of a German toilet maker.)

In retrospect, the creation of Köhler may have been a step too far. Barry said he was a Polish-German Jew who had survived the Warsaw Ghetto before being deported to Treblinka concentration camp in 1942, and at least one person online – Peter Lemken, a German conservatory graduate who went on to become an artist manager and businessman – called bullshit on Barry’s tale in 2005, and subsequently acted as a sceptic on message boards until the fraud was exposed two years later.

As Mark Singer has it in his New Yorker piece, Barry was brought down by a perfect storm that begins with something so beautifully ordinary it makes for an impeccable antidote to the absurd complexity of Barry and Joyce’s lie. An American man called Brian Ventura, who worked on Wall Street and followed classical music online, ordered a batch of Hatto records from Barry and, in the process of transferring the tracks on a CD of Liszt’s Transcendental Studies via iTunes to his iPod, noticed that the iTunes database came up with a different pianist to Joyce – a Hungarian named László Simon. He cross-referenced the tracks to snippets of Simon playing the studies on Amazon and suspected they were the same. So he emailed a New York-based reviewer for Gramophone magazine, Jed Distler, who performed his own listening test and concluded that “10 out of 12 tracks showed remarkable similarity in terms of tempi, accents, dynamics, balances, etc.” Distler tried other Hatto CDs in iTunes, discovered further clashes and promptly emailed his editors at Gramophone in the UK, who enlisted an audio expert to professionally examine the soundwaves on their Hatto CDs against the recordings thrown up by iTunes. They matched.

The game was up. Gramophone went live with their story on February 15 2007, and soon found out that, quite by random, scholars at the University of London’s Centre for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music had also discovered that a Hatto CD was a fraud, while they studying different recordings of Chopin’s mazurkas. Barry was questioned, denied everything, then let slip a week later in a letter to the head of Swedish record label, whose music he had plagiarised, that he had in fact been less than honest. But he only went so far. To the day he died, on 19 October 2014, he maintained – falsely, we now know – that Joyce had played at least something on the CDs he released during her late, fake moment of fame.

The exposé of Barry and Joyce scam became a global news story, but Barry was never arrested and he said he didn’t make any money from the records. No one sued and, in fact, it’s hard to think of anyone who truly lost out in this extraordinary tale, other than perhaps those who forked out for a Joyce CD, and actually purchased some brilliant music by a different pianist, and the critics, who ended up with eggs on their faces. But fair play to the critics; they all, including Gramophone’s Bryce Morrison, gamely lined up to be interviewed for the Channel 4 documentary, freely admitting they were conned, and in a New Yorker podcast about his story, Mark Singer suggested that it was unfair to blame them for not smelling a rat sooner: “If someone wants to lie – and this is a really wonderfully elaborate and well-conceived con – you can’t assume that a critic is going to put a CD in that comes in the mail on a label and automatically have to ask themselves, ‘Gee, is this legitimate or not? Am I listening to this artist, or am I listening to Joe Blow.’ I mean, come on, that really isn’t the onus that should be placed on the critic.”

The pianists who were plagiarised all received a boost in sales after the story broke, and that must have amused Barry – he enjoyed throwing light on unsung heroes, including Joyce, who battled the classical musical establishment and didn’t get their just deserts. Was that what drove him? Was he, at heart, a class warrior with an axe to grind? Maybe. Or perhaps there’s a narcissistic element here – Barry proving his own genius to the world by projecting it onto his wife. Those 100 or so CDs register zero artistic achievement from Joyce, but they certainly look good for Barry. They’re his Sistine Chapel, and that’s how Singer sees the story, saying in the podcast: “This guy is an artist! He’s a con artist. And this [the fraud] is truly a work of art. In my mind, this not a morality tale at all; if anything, it’s much more a saga of some kind of strange, abnormal psychology… They [Barry and Joyce] are really detached from reality in ways that we can’t quite get a handle on. But it worked for them.”