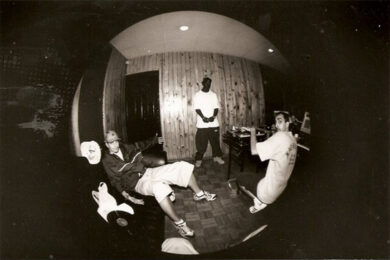

Winter in New York, February 1995. Somewhere between one and five AM, either late night Thursday 23rd or early on the morning of Friday 24th depending on how you look at it. Harlem emcee and self-proclaimed ‘devil’s son’ Big L is at the studios of Columbia University’s student station WKCR, appearing on Stretch & Bobitto’s show to promote his new single ‘Put It On’ and forthcoming debut album Lifestylez Ov Da Poor & Dangerous. He’s been asked to freestyle, but encouraged not to go completely solo given how he’s got friends with him. "If you want to put your man on too, you can do it together", he’s told. He acknowledges this, but decides to go in first anyway. "Let’s set it off like this, check it out…"

Despite the hour he doesn’t sound in the least bit weary. Quite the opposite, eleven years after he started rapping he seems amped at finally having product out there to sell. He’s having fun, playing energetically with the kind of comic violence he’s gotten a reputation for. Starting comparatively mundane, asserting the industry regulation "slugs for snitches" and "no love for bitches", a few more lines and he’s bragging comically how "bitches get fucked on the roof when I ain’t got no hotel dough". By the end of the verse he’s smoking angel dust reminiscing on his school days, happy times spent "stabbing teachers to death that gave me bad grades".

Just short of two minutes in he finishes his verse and gets ready to pass the mic to his man. "Word up" he says, "I got my man Jay-Z here", and with that Jay takes the mic. He sounds excitable, babbling about how he’s just got out of an R&B party down at the city. "That shit was hectic, man, cops in there with shotguns and all that." He maintains the energy for his routine, but nevertheless comes off weedy next to the devastating postures of L. An amiable gentleman warning how he’s going to "disrupt the natural scheme" where Big L comes nasal and agitated, warning how you’re about to "get a Tec stuck down your throat". It’s not that Jay disgraces himself, he’s nice. Too nice. When his second verse collapses into scat you have to wince a little at his apology, "I’m tired, too". Which is only half the story. For all his obvious skills it just wasn’t Jay-Z’s night.

Listening back now it’s refreshing to hear today’s all conquering multinational brand sounding human, playing a junior role. It was a situation that didn’t hold for much longer. The next year Big L was dropped from his deal with Columbia Records. Around the same time Jay-Z first started to make real progress towards world domination with the gloriously obscene Foxy Brown fuelled R&B crossover ‘Ain’t No Nigga’. But the two men stayed in touch. By the time of Big L’s murder in early 1999 Jay-Z’s career had developed to the point where he was ready to expand, signing other rappers to his label Roc-A-Fella. First up, of course, was his long time protege Memphis Bleek, but after that? Following a year of hype around his self-released underground classic ‘Ebonics’ and six months of negotiations, Big L was due to sign a contract with Roc-A-Fella records the week he died.

And so their relative commercial standings were pretty much frozen right through to now. A few weeks short of 2011 and Jay-Z is promoting his The Hits Collection Vol 1 where the Big L estate stays battling over the rights to his slim legacy, cobbling together an odds’n’sods disc Return Of The Devil’s Son.

Check the fansites, trawl the YouTube comments and there’s plenty who’ll moan about how unfair that is, how L would’ve been the big star if it weren’t for a ton of bad luck. Which is so much wishful thinking. Because the same qualities that gave Big L the edge that night in 1995 held him back commercially. It wasn’t just that he made a decision to be hardcore, or that he was rhyming about some sick shit. After all, that hardly hurt Mobb Deep or G-Unit. It was more that, at least early on, he apparently lacked any concept compromise. L pictured music as a game of stark contrasts, for him the choice was simple "you turned pop, now you no longer gain props". Whereas Jay-Z? The only thing Jay-Z didn’t understand is why one brand shouldn’t be marketed to two different demographics. He tries to keep everyone happy, famously dumbing down for his audience to double his dollars, considering no gimmick too obvious or naff, rounding out his albums with just enough substance to please more demanding listeners.

By design it’s been a strategy with mixed results, something The Hits Collection can’t help but reflect. A few times, it’s worked spectacularly. ‘I Just Wanna Love You’ succeeds despite boneheaded lyrics through sheer exuberance and the Neptunes at their aluminium plated best. ‘Big Pimpin” does a similar trick substituting the sci-fi for racy Egyptian Timbotronik funk. ’99 Problems’ goes further still offering a few smart words to go with the anthemic big beats and pilfered concepts. Other tracks fare less well, ‘Hard Knock Life’ comes with a hook so nauseating you’ll be too busy picking bits of yesterdays dinner out your teeth to even hear Jay’s verses. ‘Run This Town’ never escapes the way Rihanna warbles her part with all the rebellious swagger of a mayoral assistant running off a few sneaky personal photocopies on her lunch break.

The Hits Collection features all of these alongside another ten selections from his back catalogue. All but two were singles (‘Encore’ and ‘PSA’ being the exceptions). There’s an unfortunate bias in favour of tired, desperate, recent material (‘DOA’, ‘Empire State Of Mind’, ‘Show Me What You Got’, ‘Roc Boys’), and the sequencing appears almost random. But it’s the overall effect that disturbs, the sugary arrogance that energises in small doses enervates in overdose. There’s no ‘Song Cry’, no ‘Regrets’, no ‘Ignorant Shit’ to balance the meal. Unappetising, like taking the meat and veg out of your beefburger to leave a bap, an ugly splodge of lard and some dubious chemicals.

Committed fans won’t care, they’ll have all this stuff already. It’s not for them. Casual fans deserve better.

Strangely enough, much the same could be said about Return Of The Devil’s Son, albeit for different reasons. It’s Big L’s second posthumous album, a full ten years after his sketches for a projected Roc-A-Fella project were polished up and released on Rawkus as The Big Picture. There’s no such grand concept binding this one together, it’s a wide ranging collection of demos, freestyles and errata from his last seven years of life.

Which is way more appetising than it sounds. Never successful enough to get complacent or grown enough to get truly disillusioned, pretty much everything that’s emerged so far is of a reasonably high standard. It’s impossible to speak on the three albums worth of tracks allegedly still in the vaults, but based on what’s out there now it would take superhuman effort to put together a bad Big L album. This ain’t that. But it’s nothing new either, just a reclamation of moments long since taken for granted by the cognoscenti.

For the rest of us it’s essential by default, if only for the long overdue reissue of L’s 1993 debut single ‘Devil’s Son’. Scandalously obscure, its four minutes of rancid funk easily rank with the best of a year whose other notable releases included Enter The Wu-Tang and Doggystyle. This is cartoon L at his sardonic best making Gravediggaz sound like PM Dawn, before the label started ragging on him to tone it down. He’s pistol whipping the priest every Sunday, he’s known for "killing and raping nuns". He’s "catching more bodies than abortion clinics". Some kid shoots him in the chest but it’s no biggie, "I just laugh and spit the shell out". To cap it all he uses the outro to go off like ODB, in a heartfelt series of shout-outs declaring solidarity with "all the murderers, thieves, armed robbers, serial killers, psychos, lunatics, crackheads, mental patients, mental retards," and, of course, tastefully saving "a special shout-out" for "all the niggas with AIDS".

It’s a performance so powerful everything else risks seeming weak in comparison, a situation not helped by its position near the top of the running order. Ripped and resequenced chronologically with ‘Devil’s Son’ somewhere in the middle the disc makes a lot more sense. So you start with the hunger of the 1992 ‘Audition’ freestyle over Marley Marl’s ‘Symphony’ where L says nothing much substantial in impeccable, almost old school style, asserting how he’s "brighter than Einstein" and makes emcees "cry like onions". Then there’s the brace of early demos that got him a record deal, more straight-up battle rhymes but a creeping regard for structure and concepts. Like the hardcore mission statement ‘I Don’t Understand It’ (here re-titled ‘MC’s What’s Going On’) and the aptly titled party joint ‘Unexpected Flava’ where he explains how, now he’s gotten a bit of money "I need surgery to get chicks removed from my dick". ‘Devil’s Son’ and two other Lifestylez era leftovers, ‘Schooldays’ and ‘I Shoulda Used A Rubber’ continue his growth as a storyteller, embellishing the legend of Big L the mack who "slid a chick everyday after last class" but isn’t beyond getting burned occasionally. Finally towards the end you’ve got brace of tracks from aborted 1996 sessions for a second Columbia album showing how heavily influenced he was by Jay-Z already, how he’d started to expand his horizons. ‘Power Moves’ in particular is a virtual rewrite of Jay-Z’s debut single ‘In My Lifetime’ with L expressing newly discovered jet-set aspirations over opulent, languid soul grooves.

Played that way, rounded out with a generous selection of hyperactive freestyles, finishing up with two vicious Mase-dissing minutes taped just a few days before he died, shorn of the superfluous posthumous blends (thankfully there’s only two of these), it’s a different album. Played that way you’ve not only got quality music, you’ve got a great story. A moving portrait of a man who didn’t quite learn his lessons fast enough, whose extraordinary talent alone couldn’t buy a way out of the ‘hood.

In a sense it’s pretty ungracious to complain about the presentation, some might argue we should be grateful these recordings are being cleaned up and made more widely available at all. But it’s wrong to look at it that way. As Angus Batey argued recently in The Guardian, hip-hop heritage deserves to be treated with the same reverential care as the landmark records of rock, jazz, blues and soul. Cos it’s not just casual fans looking for a way in who deserve better, the music does too.