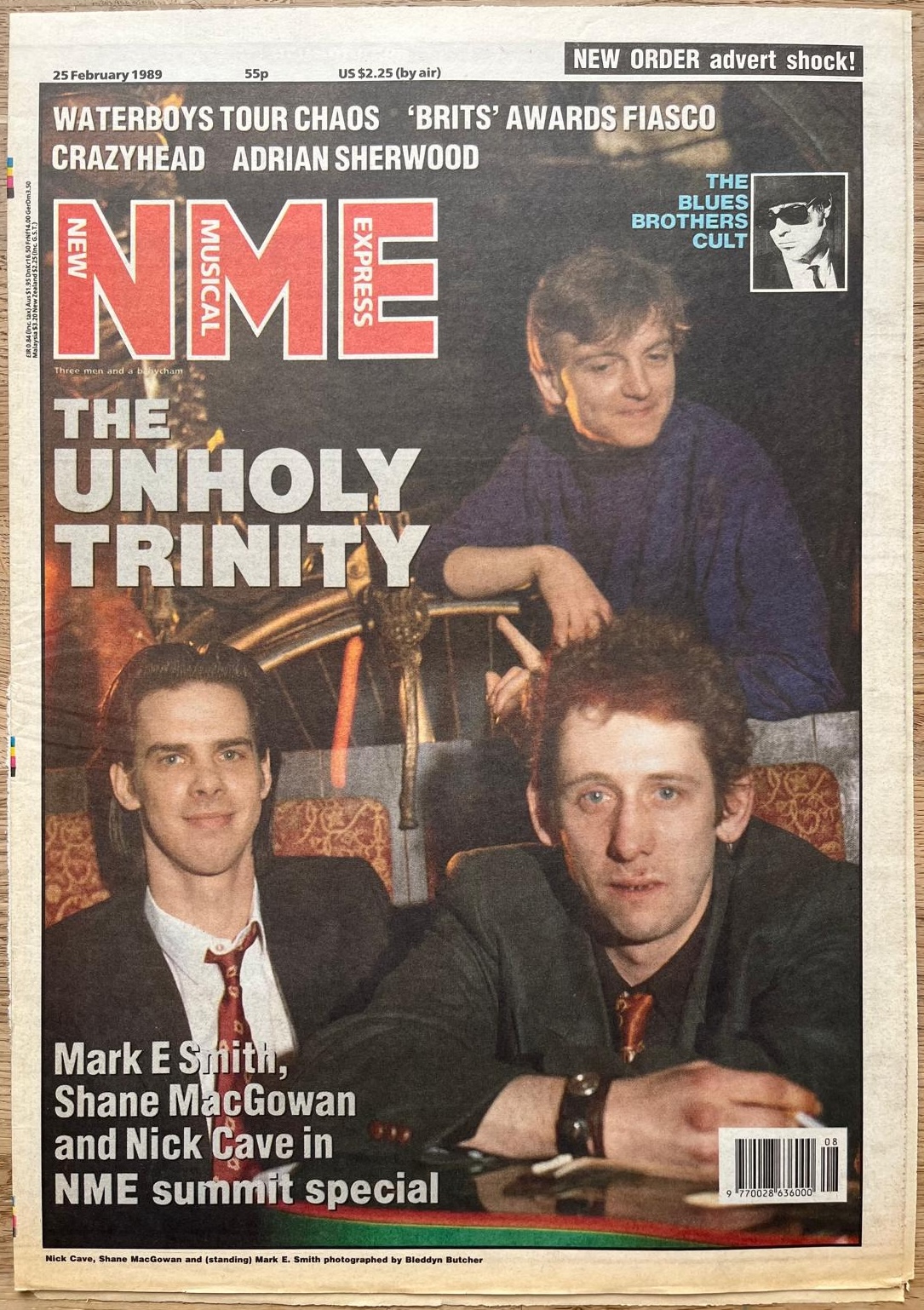

“You, Mark, Shane and Sean were all in the living room shouting, listening to music and doing speed and I was in the kitchen having a cup of tea with Bleddyn and Nick talking about Australia.”

The Mark is Smith, Shane is MacGowan and Sean is my fellow NME writer O’Hagan. Bleddyn is Butcher the music photographer and Nick is Cave.

The person remembering the famous NME cover story is Julie Jackson, a painter who was my girlfriend at the time, and she’s describing what was going on in her kitchen at the end of a very long, loud and memorable afternoon that stretched into the early hours of the following day and finished when Shane departed with my copy of Nick’s book And The Ass Saw The Angel. Later Julie told me that just before he left Shane said, “I’ve got £1000 in my pocket and if you kiss me I will give you it.”

It seems like a good starting point to look back at my late 80s early 90s friendship with Mark E Smith. When I did the Oh Brother podcast as a guest of the former Fall rhythm section, The Hanley Brothers, recently some Fall fans and the former band members themselves said I’d given some insight into Mark’s personality and lifestyle that they’d not previously encountered so I thought I’d get some of it down in writing.

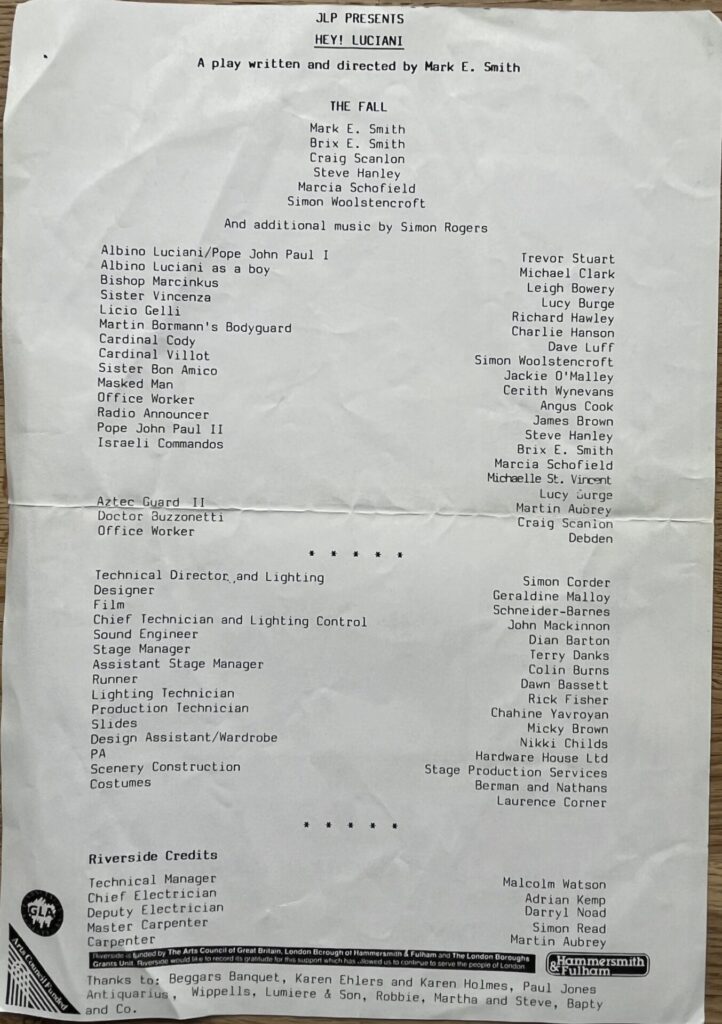

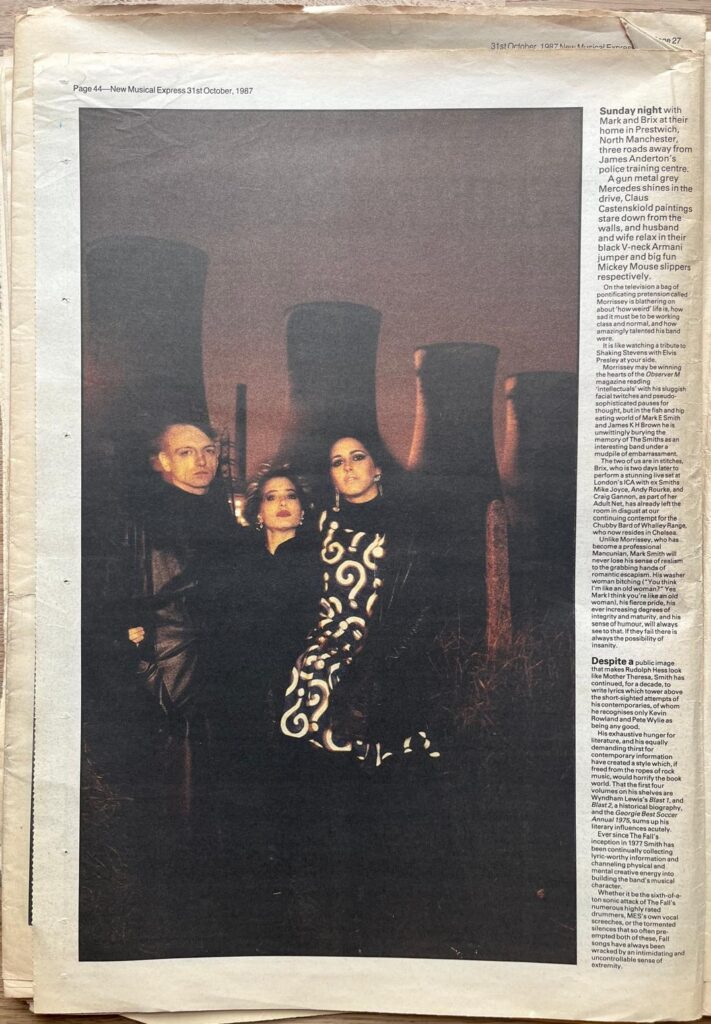

For about five or six years between 1986 and 1992 I’d see Mark regularly, we’d go to the pub if he was in London, he sent me letters, books and records through the post. I’d visit the home he shared with his then wife Brix in Prestwich and he’d stay at mine in Camberwell where we shot the non Montague-arms images for the NME Un-Holy Trinity piece. I’d get a dressing room view of his brilliant I Am Kurious Oranj production in Holland and Edinburgh and appear in his play Hey! Luciani.

Later he got a nark on that I wouldn’t feature him in Loaded, the magazine I launched after I left NME, and mentioned me in some ranting track about media figures but for that time when I was in my early twenties and he was in is late 20s and early 30s he was a great person to be with and for some reason he liked me knocking about.

When I wrote my memoir, Animal House, about my time as a music fan, NME writer and magazine editor, I looked back at that timescale and came to the conclusion the time I spent with him was largely just beneficial to his career and coverage but then I remembered just how young I was when I first met him, a teenage fanzine writer turning fledgling freelance music writer, with no real influence to exert in his favour. So I called Brix and asked her what that was about?

“Mark was a very very quick judge of character, it was black and white, he would decide if he liked someone or not on the first impression. And there were people like you and Michael Clarke who he liked having around. He liked your energy and he could see you were smart. Also you were so young and different to a lot of the music writers he met.”

Like many of you I regularly see that famous photo of Nick Cave, Shane MacGowan and Mark E Smith posing together as it makes its way round social media. It was republished with permission in The Quietus. Sometimes I read the comments underneath and it’s interesting seeing how people interpret what that day might have been like compared to what it actually was.

The idea for the feature was hatched during a pretty ordinary NME week, where writers profiled artists for readers who shared their passion, but it has become a prime moment in music journalism history.

As the 23-year-old NME features editor at the time it was my job to make sure that every week we had a good cover story that would appeal to the readers, sell copies and continue to capture and lead the musical landscape of the day. The strategy in 1998 was to mix new and up and coming acts like PJ Harvey, House of Love or The Charlatans with mainstream artists like Kate Bush, Bananarama or Def Leppard and NME favourites like Morrissey, The Fall, The Pogues, New Order, Public Enemy or the Pet Shop Boys. The policy was working and the sales were increasing and the paper was thriving again.

The then editor, Alan Lewis, was very keen on getting different musicians together for exclusive interviews and the decision to combine Mark, Nick and Shane came about during an editorial meeting where we were trying to come up with the ultimate example of this editorial device.

I knew Mark E Smith well enough to persuade him to do it, Bleddyn did the same with his good friend and fellow Aussie Nick Cave and Sean likewise with Shane, as he frequently profiled The Pogues during their rise.

The interview took place at a neo-gothic pub in Deptford, London called The Montague Arms but the photo with the off-white background is in my kitchen in a large basement flat at the very top of Champion Hill in Camberwell, South London where I lived with Julie, and her brother, Mark, who owned the place.

In terms of people’s perceptions that the day was a relentless alcoholic narcotic riot: Nick was sober, having just got clean, Shane was on acid and the rest of us… Well you’ve read her description of how the night progressed.

I write about the interview and the day in more depth in my book but how we produced the feature was indicative of the relationships some NME people had with certain artists.

There are purists who think writers shouldn’t be friends with their subjects but try balancing that with the reality that not only do you admire a subject but that they seem to like or appreciate you or your writing about them too. That you encounter them time and time again for interviews, at gigs, on tours, at other bands’ gigs and festivals, means inevitably sometimes friendships form.

For instance Mike Scott of The Waterboys shocked and delighted our reviews editor Stuart Bailie by sending him an advance tape of a new album with a note saying he was the listener he’d thought about whilst recording each song. Then there was Steve Lamacq who would use his annual holidays to get in the back of a van and go on tour with Senseless Things and Mega City Four.

I first met Mark E Smith when I was 19 having moved to Manchester from Leeds. Living in the south of the city with a member of the band Big Flame I was invited to play five a side football down the road in Sale with former Fall guitarist and future 6Music DJ Marc Riley and his mates from their label In Tape. Marc lived in a flat in the same old mansion as his former bandmate and friend Craig Scanlon, who was still in The Fall, and I occasionally went up to Craig’s to watch films.

It was Craig who introduced me to Mark Smith back stage at The International in June 1985. That was the Manchester venue where you used to see the young Stone Roses setting up and taking down the stage as it was owned by their manager, Gareth.

At that point I was still doing my fanzine as well as submitting reviews and interviews to Sounds and I recorded a few Q&As with Mark but don’t remember doing anything with them. In July 1986 The Fall performed alongside New Order, The Smiths, Pete Shelley and OMD at The Festival of The Tenth Summer at the GMEX centre, a key moment in the city’s musical history and probably the best gig I ever attended. It was alive with confident, brilliant artists whose influence was sowing the seeds of ambition in a younger generation like The Stones Roses, Happy Mondays, Inspiral Carpets and 808 State who would soon follow them.

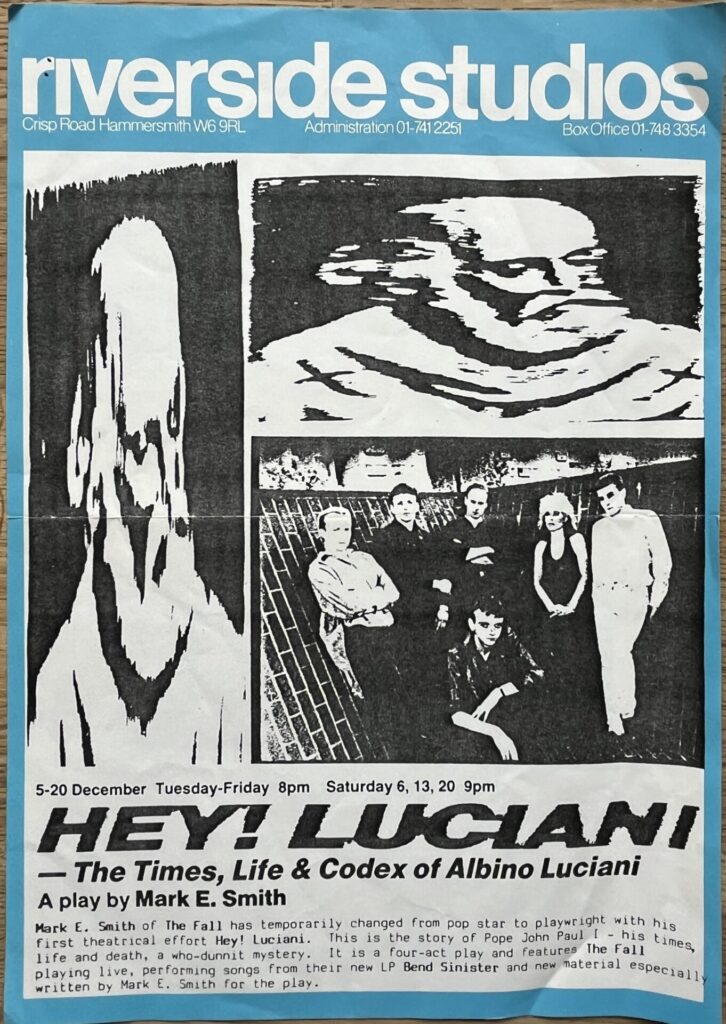

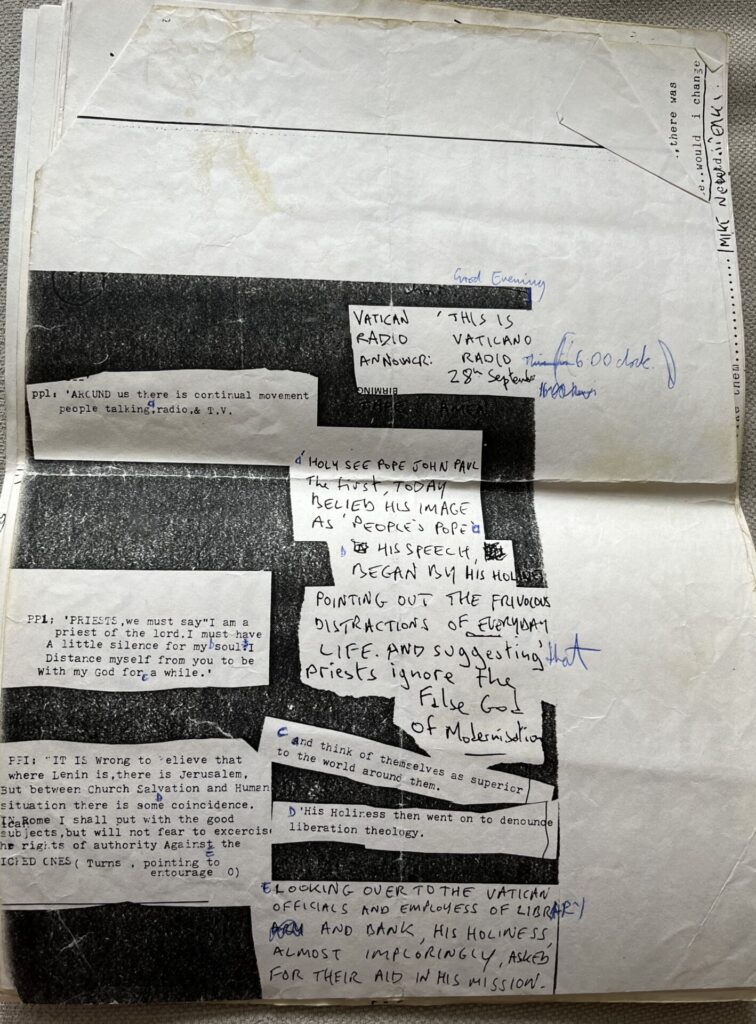

Later that year I moved to London and found myself in the St John’s Wood flat of the Fall manager John Leonard, interviewing Mark and Brix for Sounds. The band had just released the excellent Bend Sinister album and during the interview Mark mentioned he was writing a play about Pope John Paul I who in 1978 had died 33 days after being elected. Like Mark I’d read the David Yallop book that claimed the Pope had been murdered by colleagues to stop him helping liberalise access to contraception in the third world and I cheekily asked Mark if I could be in the play.

Feature continues after images

I was 20 years old, sleeping on a mattress on top of two scavenged wooden pallets in a council block in Bow, and going to gigs and writing about them was my life. I had no acting experience but the idea of hanging round with The Fall in Hammersmith for a couple of weeks seemed like a great thing to do. Surprisingly Mark agreed and said “Yes I need someone to play the Vatican Radio Announcer.”

There were a few rehearsals, far too few for the actor playing the Pope’s liking, and then we were off. Two weeks of spending five minutes on stage dressed as a Vicar miming to a Latin announcement and then loitering backstage with Mark giving me the megaphone he used to use on stage telling me to blast the sound effects buttons when ever I fancied disrupting proceedings. Disruption was very much Mark’s way of doing things. He’d assembled a brilliant cast of people and was more than happy for performance artist cum fashion icon Leigh Bowery to run across the stage midway through to put the real actors off their step.

As for the band, or ‘The lads’ as Mark called them – Simon on drums, Craig on guitar and Steve on bass – they had one dressing room and Mark and Brix had another which I spent most of my time in. They seemed to like having this young suede-headed gobshite around making them laugh and I got to see a lot more of his personality than you could decipher from watching him on stage. Despite the sometimes cantankerous nature of his performances I never had to tiptoe around Mark. He had a good sense of humour and was quick to laugh.

After that I used to see him a lot. He was brilliant company giving me books like John Waters’ Crackpot and sending speed to me at the NME office in an empty Sky Saxon album sleeve.

Despite being contemptuous of so many other bands or public figures he was always incredibly polite to anyone doing a regular job like a waiter serving him Dahl soup in the Indian in Camberwell or a minicab-driver dropping us off somewhere. If I introduced him to mates he was invariably friendly whilst working out how much of a wind up he could have with the person. He was far friendlier and accommodating than people assumed he would be.

He was more than happy to talk to anyone but would be quick to strike chords of agreement or disagreement. He always asked after my family as he knew my mum was ill. One of the main things I remember is his quick wit and insight, referring to All About Eve as ‘the Canterbury Revenge”. It was typical of the volume and breadth of his reading that it allowed him to quickly place someone in a historical context. When I asked him which of his contemporaries he rated he name checked “the Dexys bloke” Kevin Rowland and said he liked Echo & the Bunnymen who, in their very early days, had just turned up uninvited to his house to meet him.

Around the time of ‘Hit The North’ the great NME photographer Steve Pyke and I went up to Mark and Brix’s house in Prestwich where Mark had a map of the world with two Man City player Panini stickers stuck on it on his dining room wall. He immediately warmed to Steve and tolerated having to stand in a fast rushing roadside stream whilst Pyke attempted to frame Brix and Fall keyboardist Marcia with two huge cooling towers in the background.

I stayed at that house a few times. One time Brix was away and I stopped over the night before on my way to appear on Steve Barker’s excellent On The Wire radio show at BBC Radio Lancashire in Preston. Mark liked Steve but he liked speed more and after being up all night I was too fucked and paranoid to go all the way to Preston which Mark had told me was full of witches and devils and we spent the afternoon stuck to the warm radiators listening to the show as Steve announced I would be joining him, then wondered where I was, and finally decided I probably wouldn’t be making it. I had called the radio station to apologise but there was no-one on the (s)witch board on a Sunday afternoon.

Mark was at my flat when his relationship with Brix crashed, which was not a great moment. I really liked Brix and knew that along with ‘the lads’ she was a key reason The Fall had enjoyed such a fine period of creativity. But there were other more enjoyable moments, like when I commissioned him to write something for the NME and had to turn a really long, wild set of handwritten notes on multiple pieces of paper into a finished double page spread. And the time Julie and I spent in Amsterdam at the Royal Premiere of I Am Kurious Oranj.

After I left NME I managed a mate’s band for a while and Mark had them support The Fall at the Ritz in Manchester. Afterwards I saw a different side of him, sneering that music writers shouldn’t enter the music business itself.

When I was at Sounds I’d turned down managing the fledgling KLF (then known as the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu) and at NME I’d turned down the opportunity to join RCA as an A&R man after they’d signed two bands I’d championed in Pop Will Eat Itself and The Primitives. But here I was essentially just fucking around with some mates. And it seemed to annoy him. He’d been happy enough to put us on but no longer choosing the NME covers maybe I was of less use.

Around the same time I launched Loaded Mark started to appear in the music press in a very different state to that I’d previously known. Really pissed, deliberately obtuse and provocative, picking fights, pretty much the mad drunk in the corner of the bar hating everyone and everything. It wasn’t just the drinking that put me off having him in the mag, with Brix gone since their break up the music seemed to be slipping down hill and these interviews were really portraying him in a very poor light. I didn’t like seeing someone I’d admired so much slump into an alcoholic parody.

In late 1994 I sent him Ray Davies memoir, X-Ray, when it came out and Mark wrote back telling me he’d recently been hospitalised after a party at his house had ended up like a shooting gallery. He didn’t mean fairground ducks and cork pop guns. I went to see the Fall a while after that and he was on stage ad-libbing pissing and moaning in a lyric that I wouldn’t have him in the mag but had the nerve top get on the guest list. Backstage after we had a brief chat. Over the coming years he seemed to slump into an even worse alcoholic state and stories went around amongst those that had previously known and loved him about the depths to which he was descending.

Years later when I was co-producing Flipside, a very rough indie version of people watching TV live and talking about it, a format that would go on to “influence” Gogglebox, I asked Mark to come on but he was a nightmare. Pissed, incapable of following the format, quarrelsome and rude. Keith Allen had turned up at another broadcast in the same state but had managed to manifest his drunkenness into a very funny performance whereas Mark was just worse for wear.

I last saw him at 93 Feet East, a small venue down Brick Lane, London I’ve no idea what year it was but it was a remarkable moment. I’d been at a party over the road when someone mentioned the Fall were on opposite so a mate and I tried to blag in. The bouncer wasn’t having it, so we went round the back and climbed in through the toilets. On stage Mark was doing the last few numbers of the set supported by blokes who looked like the crew of the Arkansas Chugabug from Wacky Races, complete with the big beards and plaid shirts that had come in with grunge; they were making a hell of a sound.

When Mark finished they stayed on playing and I nipped backstage to quickly say ‘Hi’ and he seemed really shocked and pleased to see me. He was alone and pacing and full of the energy of the gig and smiling but the amazing thing was he seemed totally sober and straight. We had a laugh and I left, I was pleased he was in such good nick and I’m glad that’s the final personal encounter I had with him. A year or so before he passed away Dave Haslam, the DJ and author, texted me and said he’d seen Mark in hospital and that he could well be on his way out and that he thought I should know.

I called the hospital the next day and they told me he’d checked himself out. Thriving to die another day. His post mortem legacy has preserved his status in a better light than I’d feared but there was no doubting his unique perspective on the world. He would not be limited.

James Brown is the author of Animal House (Quercus) half of which is about music, you can buy it signed and dedicated direct from him @jamesjamesbrown on Twitter and Instagram