Every Iranian I know has, at some point, been personally sent a death threat, arrested or tortured by agents of the Islamic Republic. Even the luckiest ones know someone who has suffered a fate that is similar or worse: they have a loved one or loved ones who have been disappeared or murdered.

Right now, the Iranian dictatorship is currently in the middle of its most deadly crackdown since its bloody inception in 1979. Since late December, huge numbers of protesters have been fatally shot or stabbed in the streets by the IRGC (Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps). Thousands more have been deliberately blinded, arrested, tortured, or executed in cold blood while being treated in hospital. The regime itself has admitted to around 3,000 dead. Other credible estimates put the appalling death toll much higher: 30,000 to 35,000; with unverified stats from Canadian NGO the International Centre for Human Rights putting it at over 43,000 killed and over 10,000 blinded during the last five weeks.

After so many waves of repression from the Islamic dictatorship, and with so many well-documented protests across the decades, it’s hard to believe anyone would seek to question the authenticity of the recent uprising in Iran. And yet the internet has been rife with conspiracy theories that have been, at best, misguided and at worst dehumanising to the thousands of Iranians who have been arrested, injured and killed in this crackdown.

Some of these debates have been bleakly funny. My most surreal interaction so far was from a musical acquaintance who posted a quadriptych of the late Queen Elizabeth sporting a range of headscarves with the question, “Are women forced to wear hijab, or is it more like Britain in the Fifties?” Adding, “My Mum would put on a headscarf even if she popped to the shops”.

It is true that these latest Iranian protests didn’t stem from compulsory veiling laws (assuming that was his muddled point). But it was only in 2022, after Mahsa Jina Amini died suspiciously following detention in a hijab re-education centre, that the regime’s appalling track record of gender-based violence helped inspire Iran’s Woman Life Freedom protest movement. Women have been resisting dress code laws ever since, but the law in Iran hasn’t actually changed to protect them. They are just bravely ignoring the rules, even using apps to warn each other if the Orwellian “morality police” are nearby. However, the regime will still make an example of dissenting voices, particularly artists with a big platform.

The recent uprising began with the bazaari market holders protesting over Iran’s collapsing economy. This has been exacerbated by the US / Israeli attacks on Iran last summer and follows years of cruel economic sanctions from the West, which have caused significant suffering to innocent Iranians.

Some have speculated that Mossad / CIA agents planned and encouraged the latest protests and Iran certainly does have a long history of foreign interference. Operation Ajax, the military coup against the democratically elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, was orchestrated by MI6 and the CIA, largely to safeguard western oil company interests. Before that Iran also suffered criminally under-reported, cataclysmic famines during the first and second world wars caused by occupying Ottoman, British and Soviet Russian forces.

But however much US or Israel may covet regime change in Iran, the current wave of protesters have been expressing their own justified anger over the Islamic regime’s mishandling of the economic situation and a range of other grievances regarding human rights, workers’ rights, women’s rights, corruption, censorship and repression of democracy. People from all walks of life have joined the protests with devastating consequences for themselves.

Meanwhile, here in the UK, in our comfortable liberal free-speech safety zone, their voices are consistently shouted down by self-styled anti-imperial dogmatists, intent on painting the Iranian regime as a heroic bulwark of resistance to Israel, America and the evil “West”.

This debate is personal for me, and not some zero-risk intellectual point-scoring exercise for white British hard-left blowhards with a moral blind spot for murderous dictators. Alongside my small profile as an independent musician and theatre-maker, I have had a long-running sideline organising creative activities in community settings. For several years this has taken the form of music and art activities with children and families in asylum settings for arts and well-being charities like Hear Me Out. All these spaces have had a significant cohort of Iranians, who currently rank in the top three nationalities for UK asylum applications.

Nigel Farage and Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, aka Tommy Robinson, have also been trying to hijack the protests in order to serve their Islamophobic agendas. Both claim to support “brave Iranian protesters” but the vile, hypocritical racist Yaxley-Lennon also participated in marches against hotels and reception centres in Essex that support Iranian asylum seekers. The children I meet via Hear Me Out have to navigate the double trauma of fleeing danger in their homeland only to suffer hate directed at them by racist British mobs.

I’ve got to know many Iranian refugees through this work, including the dazzling setar and daf virtuoso Zanyar Hesami. Zanyar fled Iran in 2022 after becoming involved in the Woman Life Freedom protests, composing impassioned protest songs as well as marching alongside “brave young women, some as young as seventeen”. Because of this, it has become impossible for him to return to Iran, but he has just released a haunting ballad called ‘Che Javanani’ (Such Courageous Youth) which is accompanied on YouTube by raw footage of demonstrations. He calls it a “memorial for the thousands of brave young people stolen from us”.

Zanyar is also using his platform to post about Kurds being targeted in Syria and like many of us, he is frustrated at the way Middle Eastern people are selectively supported over here, as if murdered Iranians are the “wrong” kind of Brown victims. “Iran is a police state,” he says. “Censorship, torture, arrests, and killings are the daily reality for people there. Defending the dictatorship in the name of fighting imperialism is an insult to people of the region. Iranians, Kurds and Palestinians all have the same right to freedom and dignity.”

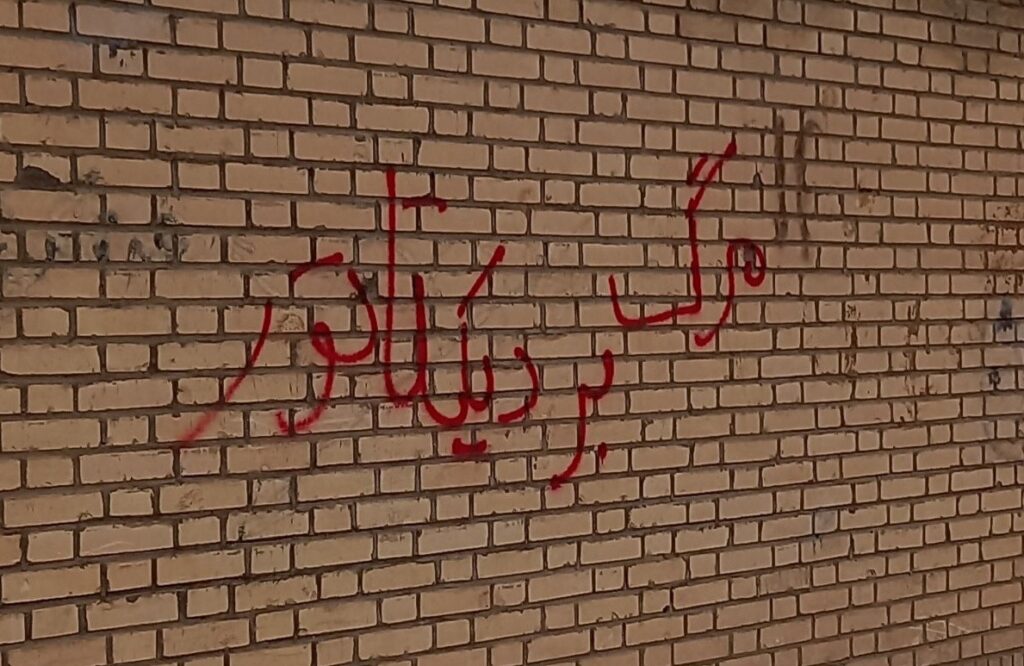

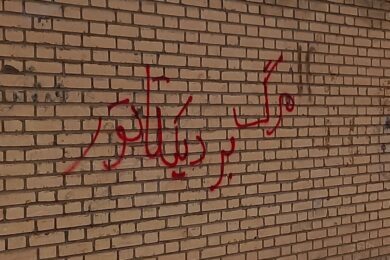

Afi, a talented visual artist in her twenties, also had to escape Iran after attending Woman Life Freedom marches in 2023. Because she was caught on camera, she now faces grave risk of being identified and punished. Even so, she felt compelled to march in solidarity. “When a woman’s voice, body, or basic personal choices are criminalised, art stops being just an act of expression and becomes a constant negotiation with fear. These restrictions don’t only limit what can be produced; they slowly shape how a person sees themselves. “

Like many other Iranian protestors, Afi recalls how marches they attended were broken up by violent gangs who “spoke in Arabic” and acted like “professional imported militia”, attacking people with brutal efficiency and dragging them away in vans. There is overwhelming evidence supporting these testimonies and that the most recent demonstrations have been suppressed in the same savage way by IRGC with reinforcement from armed Iraqi, Afghan and Hezbollah vigilantes.

On 21 January Iran’s own Supreme Council of National Security issued a statement admitting that 3,117 people were killed in the recent uprising. However earlier, on 16 January, Mai Sato, the UN Special Rapporteur on Iran, claimed at least 5,000 deaths had been verified, adding that medical sources suggest the death toll might be 20,000. And yet, once again, many of the same armchair experts who defer to Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur to occupied Palestinian Territories, are ignoring Mai Sato despite her parallel mandate and harrowing UN address on the atrocities in Iran. I struggle with this discrepancy because, just as Netanyahu bans international journalists from entering Gaza, the Iranian regime routinely impose nationwide internet blackouts for the same reason – to block visibility while they get away with murder.

I have been speaking to Iranian diaspora artists outside of the UK, and am very glad to get the perspective of Calgary-based NUM. Originally hailing from the North of Iran, they are an electronic duo consisting of vocalist/sound artist Maryam Sirvan and composer/technologist Milad Bagheri. Their music, which encompasses processed vocals, field recordings and digital soundscapes is enigmatic and mercurial. Sirvan’s ever-changing voice, ghosts in and out of the atmospheric textures. Perhaps the fluid nature of their sound is, in part, a product of the intense censorship they’ve faced in Iran?

As they explain, “The laws there attack artistic freedom and for our duo, it was even more personal because Maryam is a female vocalist and performer. At any point, you can be shut down, arrested, intimidated, or pressured into deleting your work and your social media posts. That constant threat shapes everything you write, perform and publish, and how visible you allow yourself to be.”

NUM have also had similar experiences to me, in recent weeks, of being “Iran-splained” by non-Iranians. “As artists in the diaspora, our first responsibility is to share credible information from inside Iran and amplify Iranian voices, so the regime’s misinformation doesn’t dominate the narrative. We must keep attention on the human reality: people are being killed, imprisoned, and silenced, and the world should not look away.”

I also manage to contact a musician in Iran – who we will call “T” for their own safety. Because of the internet crackdown, communication between us is inevitably protracted and sporadic. We lament not being able to meet in person, imagining how we’d slip in and out of English and Farsi as we’d chat over cups of Persian chai. T also describes tough conditions for artists in Iran.

“American sanctions mean we can’t have outside financial transactions so we can’t sell music internationally without significant help and complicated clandestine arrangements. At the same time, we have suffocating censorship when it comes to public events, the financial situation mishandled by the government has made it impossible to operate independently. If you get through the financial hurdles they can and will deny you licenses to shut you down. “

There is a famously lively underground scene in Tehran which they have travelled to visit but as T explains, “it is dependent on money and assurances from elements of the security system. All these hurdles are just for smaller artists like me. Rappers or singers with a big following, have put their freedom on the line just to release a record.”

In 2023 I became involved with the Index On Censorship campaign to release a rapper in just that predicament – Toomaj Salehi who was at the time sentenced to death for recording tracks like ‘Normal’ which criticise the regime passionately.

Once again, conflicting interests and strange bedfellows emerged during the wider campaign for his release. A rally that year in Marble Arch was dominated by people waving Israeli flags and signs supporting the former dictator Mohammad Reza Shah with calls to restore his son to power. Salehi hasn’t expressed any support for Netanyahu or the Shah dynasty and this kind of right wing appropriation may have actually made life more difficult for him as the Iranian government regularly accuse dissidents of spying for Western enemies.

My heart sank even further when one of the rally performers chanted, “Long live the king” from the stage, ironically before playing a cover of Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick In The Wall’. Between bouts of cheerleading for Putin, Roger Waters has also been yo-yoing on where he stands on Iran. In a recent interview with Piers Morgan he claimed that Iranians, “do not want regime change”. He said that the protests were solely the result of economic sanctions, and claimed they had been whipped up by “MI6 and CIA thugs”.

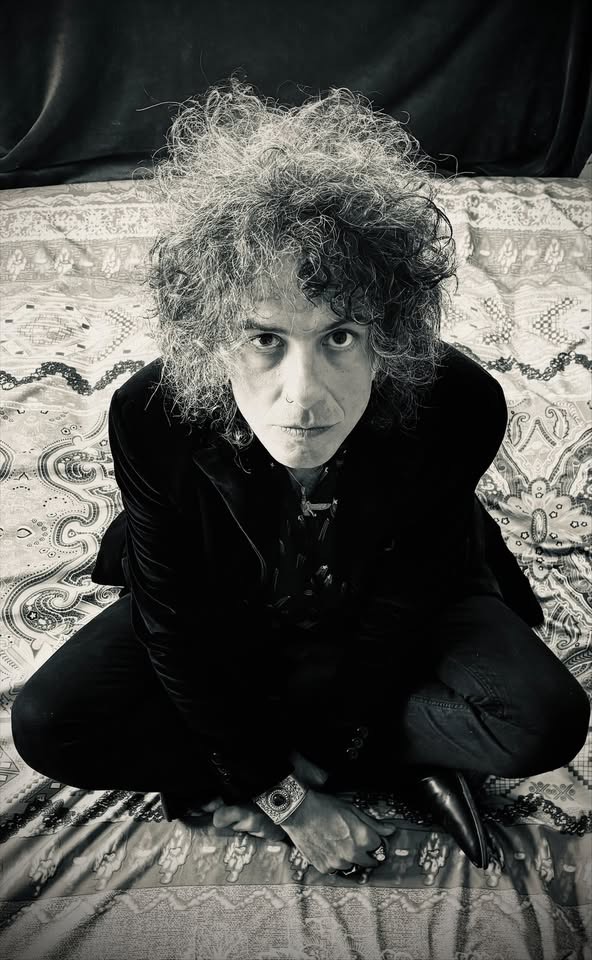

Waters has since backtracked with an apologetic, “I support the Iranian people” counter video after facing a backlash from Iranian activists, artists and social media users who accused him of whitewashing repression while tens of thousands were killed. As a famous rock star with a big following, his words could carry weight in how the world perceives Iran. Other rock musicians of Iranian origin such as Kavus Torabi of Gong, Cardiacs and The Utopia Strong have recorded their own videos supporting the protesters.

Speaking to me, Kavus says: “The unspeakable cruelty meted out upon the citizens of Iran over the last 47 years by this corrupt and murderous regime has been heartbreaking to witness in the diaspora. Every time there is an uprising, my hopes are raised and each time dissidence is punished by further savagery from the state. Given the devastating brutality rained down upon Iranians since the current uprising, I had hoped the plight of these brave people would have been amplified across the world so that finally everyone can see what we Iranians have been saying for half a century, only to see the story ignored or the narrative twisted to suit partisan beliefs or worse still, when it is mentioned, the propaganda and deception of the government repeated and spread. The Iranian people need your support. This is a humanitarian crisis. This is beyond mere left and right politics.”

Speaking from Iran, T also doesn’t mince their words about right wing Shah-supporters in the diaspora. “For me one of the most important things is resisting attempts by these right wing ultra-nationalist fuckwit monarchists who got Western institutional support to hijack the protests. They must let the left wing and liberal voices be heard and there are many of us here in Iran.”

I grew up hearing about life under Mohammad Reza Shah’s callous dictatorship from my family. My parents fled Tehran in 1976 to escape the Shah’s repression. They moved to Swansea because the university had a good engineering department for my father’s studies and on the rare sunny day they visited, it reminded them of the North of Iran near the Caspian Sea where they holidayed as children. Fortunately, my father managed to dodge an offer to become an informant for SAVAK, the Iranian secret police. He had no desire to collaborate with the enforcers used by the Shah to imprison, exile, torture and murder his opponents. This caused widespread resentment in Iran as did the Shah’s sycophantic relationship with the West which rendered him beholden to western interests.

There is a family story from my father’s cousin which encapsulates this, an eyewitness account of Henry Kissinger’s car being pelted with stones by fellow university students. Kissinger was being driven from Tehran airport to one of the royal palaces in Northern Tehran, but the chosen route went past the Men’s University dormitory, where the students took the opportunity to stone his car. “Kissinger was never so frightened in his long life as in those few minutes,” my father’s cousin said. But he also recalled how SAVAK agents later attacked the dormitory, pulled everybody from their beds, and collectively arrested many students. Unable to pinpoint the real culprit, they used violence to force people into confession. He was lucky to avoid punishment himself.

Much of my knowledge of Iran has been passed down to me by my diasporic family. However, in the summer of 1993, I travelled there as a teenager with my parents for the first and only time. I’ve talked about this visit a lot. The bazaar overflowing with fresh flatbreads, giant pomegranates, under-the-counter beer and chocolate liqueurs. The heat that felt solid, especially as I grappled with my enforced hijab. The morality police who stopped my grandmother because her tights were too thin (my stylish grandmother was very proud of her legs, even in her older years, and resented covering them up). The way my cousins laughed at my Welsh / English accent when I spoke in Farsi, and their surprise that I knew enough to recognise euphemisms about them secretly smoking opium. The bubbly women roasting corn for sale on the North coast roadside and the road we avoided in Tehran because of the executed corpses hanging from cranes.

I made a short film last year with animator Al Orange called The Paper Bag which is based on the mysterious man I met while taxi-pooling with my glamorous grandma. Several English and Farsi songs from my records also draw on snapshots from that visit. But I’ve been thinking recently about another song I wrote, called ‘Night Swimming’, inspired by swimming in the Caspian Sea with my family under the cover of darkness. Beaches in Iran are segregated by partitions. Men and women are not allowed to swim together. We realised that if we wanted to swim as a family we’d have to risk coming at night when Basij patrols were less likely.

Swimming as a mixed group was and still is illegal and solo singing about this or any other subject is banned for women. So, my song which has had airplay in various countries, would never be played on national radio in Iran. All of these basic human expressions that I take for granted in the UK, singing, dancing, splashing in the sea with my little kid and partner, wearing what I want, showing my dyed red hair, reading or enjoying any media I want, forming my own judgement about it afterwards. All of these would be officially denied to me in Iran.

The UK has just announced plans to proscribe the IRGC, after the EU labelled them a terrorist organisation last month. This is welcome news. For years, Iranians inside and outside of Iran have been campaigning for it. Sunak set a date but then reneged. Our prime minister and former human rights lawyer Keir Starmer initially wouldn’t commit to it, instead choosing to proscribe Palestine Action. The IRGC have brutalised Iranians with impunity, travelling in and out of Europe and Canada, laundering money, sending their children to international schools, threatening and attacking Iranian activists outside Iran. Many in the diaspora think there needs to be further decisive steps against these mass murderers: further diplomatic sanctions, freezing of assets and expelling ambassadors.

But as I write this Trump’s “armada” is heading towards Iran, which fills me with dread, anxiety and guilt. And yet my turmoil is nothing compared to the bravery of young Iranians fighting for a more progressive Iran. These are all the contradictions we carry as Iranians. Like my one precious, distant visit. The familial warmth, the colour, the sensory and emotional explosion of it all alongside the lurking threat of Basij, morality police and attacks from the West.

I think about the people I met in Iran as a teenager, but also about artists and musicians still living there, who are emphatic about how we all need to show solidarity with Iranians as they fight for a better future. “We must campaign hard against war,” says T. “We don’t need another war and more misery here in this country, remember what happened with Iraq?”

Roshi Nasehi is presenting a special solidarity and fundraising event at Camden People’s Theatre on 11 February. You can donate directly to MIAAN, who support digital access and human rights in Iran or to the music based charity Hear Me Out who support Iranian and other asylum seekers in the UK.

Read more about what you can do to support the protestors in Iran here