On the 31 January 1993, something weird happened in the UK album chart. A piece of contemporary classical music that had inexplicably made it into the Top 40 the week before shot up to No. 8, leapfrogging Take That’s debut, Take That & Party, and landing one position before R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People. Then it climbed again – to No. 6, where it stayed for a couple of weeks before gently sliding back down the chart and eventually falling out of the Top 40 two months later.

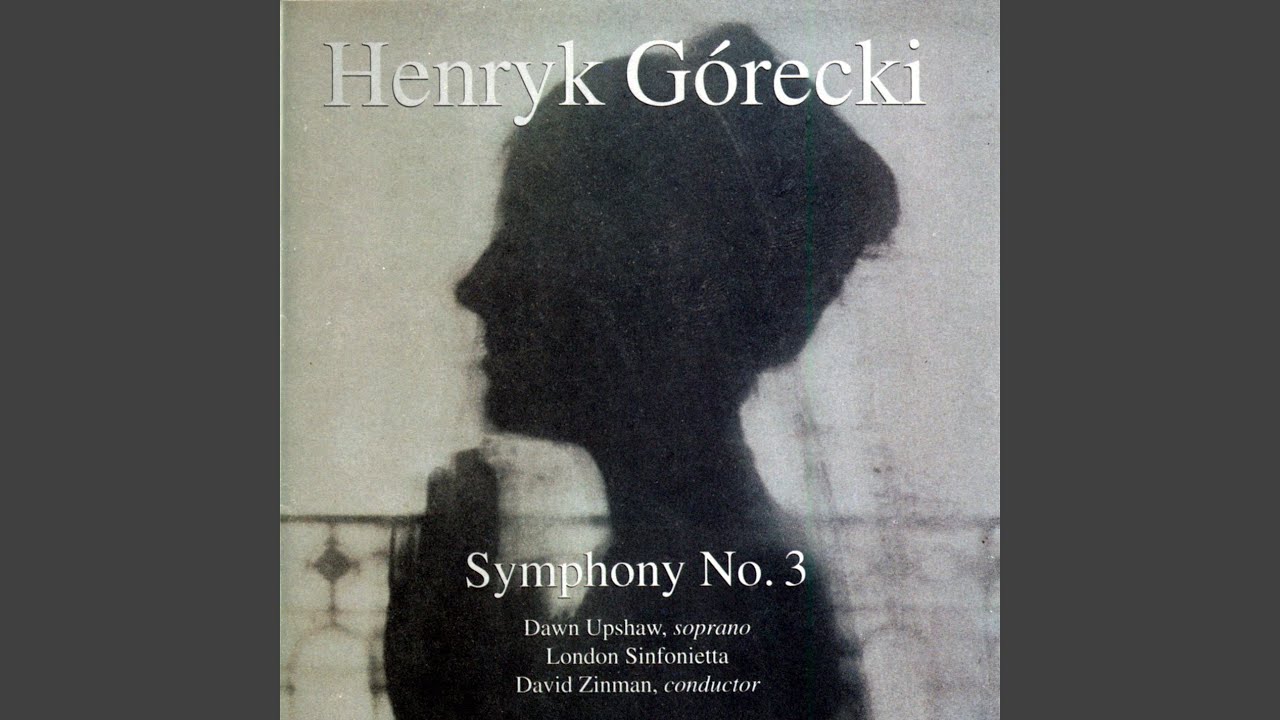

At its peak, the album – a recording of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 by the London Sinfonietta with soprano Dawn Upshaw, conducted by David Zinman – was thought to be selling between 6,000 and 10,000 units a day. It would go on to shift more than a million copies globally. In the early-90s, classical records did still occasionally crack the charts, but they usually needed famous names and some kind hook up with film, advertising or sport, like Pavarotti’s version of ‘Nessun dorma’ by Puccini – a No. 2 single after it was used as the theme tune of the BBC’s coverage of the 1990 World Cup in Italy.

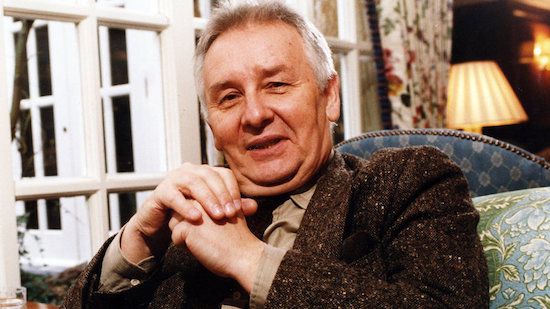

This was something quite different. Górecki, a deeply religious Pole who had been working behind the Iron Curtain, was largely unknown outside of classical music, and his Symphony No. 3 wasn’t an obvious pop hit. Subtitled ‘Symphony Of Sorrowful Songs’, the melancholy, three-movement work concerns “the great grief and lamenting of a mother who has lost her son”, Górecki said, and might also have been a memorial for the victims of the Holocaust, although he denied an explicit connection. It also wasn’t a new piece. Written in 1976, it had been recorded three times already and was hardly well-liked. Critics trashed it after its 1977 premiere in France. Avant-garde composer Pierre Boulez – sat next to Górecki – is thought to have shouted out, “Merde!” as it ended.

The success of the London Sinfonietta version blindsided everyone. Dawn Upshaw, whose extraordinary vocal performance was paramount to the album’s emotional punch, had been advised by her agent to take an upfront fee and not royalties. Robert Hurwitz of Nonesuch Records, who had been blown away hearing the work live in London in 1989 and organised the recording for the label, told The New York Times in 2017 that he was hoping to sell 30,000 copies tops. Górecki himself seemed both stunned and traumatised by what happened. “The first royalty check he got was in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and he kept it in his wallet for a long enough time that we had to reissue it, because he wouldn’t cash it,” Hurwitz said in the same article. “It may just have been such a shock to all of a sudden go from someone who had struggled to find recognition, to someone who was at that moment as famous as any modern composer in the world.”

Górecki was 59 at the time, and he wasn’t the only freak pop star of the year. Just as he was ducking the glare of international attention, no less a group than the Benedictine Monks of Santo Domingo de Silos were beginning to make serious ripples in Spain with an album of Gregorian plainsong. The recordings dated from the 1970s and early-1980s, but were packaged on CD in 1993 and marketed as an antidote to the stresses of modern life. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they first found an audience among irate commuters enduring rush hour in the sweltering Spanish capital. Radio DJs played the chants to calm drivers down, and it worked. “Gridlocked Madrileños stopped hitting each other at traffic lights and bought the disc in their thousands,” wrote Norman Lebrecht in his 2007 book Maestros, Masterpieces And Madness. “On world release [in 1994, as Chant], the monks sold five and a half million CDs, their popularity boosted by hip hop DJs who played chant at the end of all-night raves.”

What was going on? The Polish text used by Górecki in his Symphony No. 3 was taken from three sources: a 15th-century lament of Mary, mother of Jesus; a prayer-like message inscribed on the wall of a Gestapo jail cell by a teenage girl during World War II; and a Silesian folk song. To listeners, if not Górecki, Symphony No. 3 was a spiritual work and now a bunch of monks from Spain singing ancient plainsong had gone multi-platinum. Critics searched for threads. They didn’t have the audacity to clump Górecki together with the monks and call it a movement, but they weren’t shy about inventing a new genre to encompass all composers in Europe writing ambient classical music with a vaguely religious feel. Holy minimalism, they called it. Holy minimalism! But what did it mean? Essentially, the very approximate combination of the sparse aesthetics of American minimalist classical music, as espoused by the likes of Steve Reich and Philip Glass, with liturgy or sacred tradition. The key practitioners were considered to be Górecki, Arvo Pärt and an Englishman, John Tavener, who had started out in the 1960s recording for The Beatles’ Apple label.

All three had varied religious backgrounds, weren’t a ‘school’ sharing ideological and musical values, nor were they stylistically particularly similar. And, in truth, the term might never have been invented if albums by this disparate Holy Trinity hadn’t started to sell well, beginning in the mid-1980s when Pärt – an Estonian – signed to German jazz/fusion label ECM in 1984 and found a sizeable audience in the West. The gold rush continued with the runaway success of Tavener’s transportive, eight-part work for cello and strings, The Protecting Veil, which was nominated for the inaugural Mercury Music Prize in 1992, and went into overdrive when Nonesuch released the London Sinfonietta’s take on Górecki’s Symphony No. 3.

Clearly something cultural was happening here, beyond swathes of record buyers hearing Nirvana’s In Utero and Wu-Tang Clan bellowing, “Bring da motherfuckin’ ruckus!” and deciding their ears required something more soothing. In his excellent charge through post-1989 classical music, Music After The Fall, journalist Tim Rutherford-Johnson suggests that holy minimalism – a genre so specious that it may as well include the Benedictine Monks’ Chant – was “cathartic for a world that had passed through the Cold War and the threat of thermonuclear annihilation”. In essence, these records seemed to provide spiritual respite from complicated political and societal change, and maybe even a vision for a new peace.

And perhaps that’s why Domino Records – best-known as the home of Arctic Monkeys – are taking a punt on releasing a new, live version of Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 with Portishead’s Beth Gibbons on vocal duties. It was recorded in 2014, but it’s out on 29 March – the day we are supposed to be exiting the European Union – and there’s another noticeable parallel here. Nonesuch’s recording of the work took off in Britain in no small part because its second movement was hammered on Classic FM in the first weeks of the station’s launch in September 1992. Earlier this month, Scala Radio began broadcasting with a line-up of DJs that includes Simon Mayo, Mark Kermode, Goldie and William Orbit. It was the first launch of a classical music station in Britain since Classic FM and a recording of Symphony No. 3 with Beth Gibbons would appear to be right in its populist, crossover sweet-spot. So, who knows, perhaps history will repeat itself and Henryk Górecki will have another hit album with his enduring symphony, albeit a posthumous one this time – he died in 2010.

I really like this new version, which matches Beth with the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Krzysztof Penderecki – an important composer himself, born in 1933, as indeed Górecki had been. I was lucky enough to be sent a copy pre-release and I’m listening to it while writing on the morning on 25 March. Scott Walker’s death has just been announced and I can’t pretend I’m not immensely moved. In the 90s, it almost became a cliché to use Symphony No. 3 as a soundtrack to death – particularly at funerals and in films, like Peter Weir’s Fearless – placing it in contexts that Górecki could not have predicted. “I never write for my listeners,” he said after the piece became a hit. “I think about my audience, but I am not writing for them.” Equally, he was delighted that, “Perhaps people find something they need in this piece of music. Somehow I hit the right note, something they were missing. Something somewhere had been lost to them. I feel that I instinctively knew what they needed.”

There’s something delicious about this; about a piece of music that the classical music cognoscenti hated, and – with exceptions – still do, becoming so meaningful to vast numbers of people who might never have given symphonic music a go before. Nonesuch’s parent company in the UK, Warner Classics, certainly got kick out of rubbing the establishment’s nose in the work’s broad appeal, first coming up with marketing strategy that involved sending the CD to an amusingly bizarre range of ‘tastemakers’ (Mick Jagger, Enya, Tori Amos, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Basil Hume, and Norma Major) and then running double-page newspaper ads with negative comments from critics on the left-hand page and the astonishing sales figures of the album on the right.

“Spiritual [holy] minimalism became the poster child for the principle of letting the market determine the direction of new music,” writes Rutherford-Johnson, while also noting that state funding played a significant part in the creation of many holy minimalist works, including Symphony No. 3, which Górecki had composed under communism. Furthermore, there were signs that his work was going to be claimed by musicians outside of the confines classical music stretching back to the 1980s. English post-punk industrial band Test Dept, which counted the son of a Polish émigré among its line-up – Paul Jamrozy – used parts of the symphony in the introduction to their live sets, and the French director Maurice Pialat featured a section in the credits to his cult 1985 film Police, starring Gérard Depardieu and Sophie Marceau. It must have had an effect on cinema-goers; soon after, a full performance of the symphony by the Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra was released as a soundtrack album.

Nonetheless, the triumph of the 1992 version remains an abnormal occurrence in the history of the music business. And of course the labels tried everything in their powers to try and repeat its success. In 2017, New Yorker critic Alex Ross unearthed and tweeted a BMG press release from 1994 announcing “a world-premiere recording by another relatively unknown 20th century composer” conducted by David Zinman, who had been on the podium for the Górecki album. “Remember Górecki’s Third Symphony?” the bumph began. “Remember the man who introduced the work to millions of people with his chart-topping recording? Well, David Zinman is at it again…” The album – a recording of French composer Charles Koechlin’s symphonic poem The Jungle Book – sunk without a trace.

As for Górecki, he continued to work, albeit more sporadically. He certainly wasn’t going to deliver his fourth symphony on order of record bosses looking to further profit from his fame. It remained unfinished when died in 2010, but was completed by his son and premiered to much fanfare by the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall in April 2014. It’s a fascinating piece that Alex Ross called “a conscious summing up”. And perhaps it contains a wry joke or two within the score. It begins densely with organs and three bass drums before, Ross writes, “a turn toward a stereotypically ‘Górecki-like’ hymn for low strings makes one think that a contrasting, consoling second movement is under way. Indeed it is, and yet the onslaught of the opening immediately resumes… The composer lures his listeners into a trap created by his familiar style, and proceeds to clobber them.” Holy minimalism was well and truly over.

Henryk Górecki: Symphony No. 3 (Symphony of Sorrowful Songs) performed by Beth Gibbons and the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Krzysztof Penderecki is out via Domino on Friday